1954 was an interesting year for American popular music. Charlie Parker was coming to the end of his earthly run, but his frequent collaborator Miles Davis was kicking his own drug habit and finding the distinctive voice that would open up years of amazing creation. Thelonious Monk switched labels, from Prestige to Riverside, a move that opened his way to the best work of his career. Frank Sinatra meanwhile had moved from Columbia to Capitol and made the first of the albums for that label which together constitute one of the greatest legacies of American popular art.

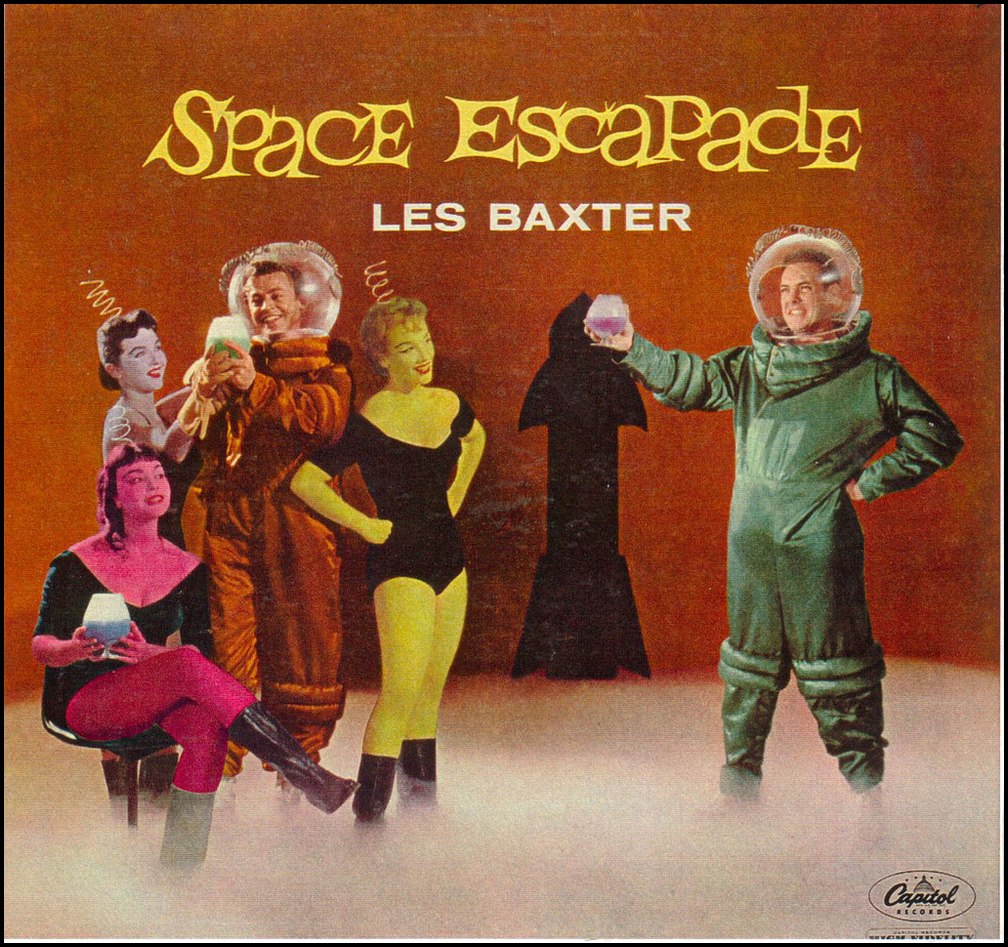

Ella Fitzgerald was in the midst of a change as well, moving away from her showy scat and novelty numbers to quieter, and utterly brilliant interpretations of the great American songbook. Jazz artists like Jimmy Giuffre and Chet Baker were developing a distinctive West Coast sound, cool and laid back, even as the pioneers of bop grew thornier, challenging convention in bolder and bolder ways. Anita O’Day, feeling her oats as a solo performer, was adding her own flavor to the cool West Coast sound.

The Big Band era was all but over. The logistics of taking a large ensemble on tour no longer made economic sense. Swing ensembles got smaller, even as they faced competition from the hard-driving R & B groups that appealed to younger listeners. In 1954 Elvis Presley recorded the proto-rock “That’s All Right, Mama” for Sun Records, a regional hit for the label, and Bill Haley recorded “Rock Around the Clock”, which became a national break-out hit when it was featured in a popular movie. The rock and roll locomotive was getting up steam.

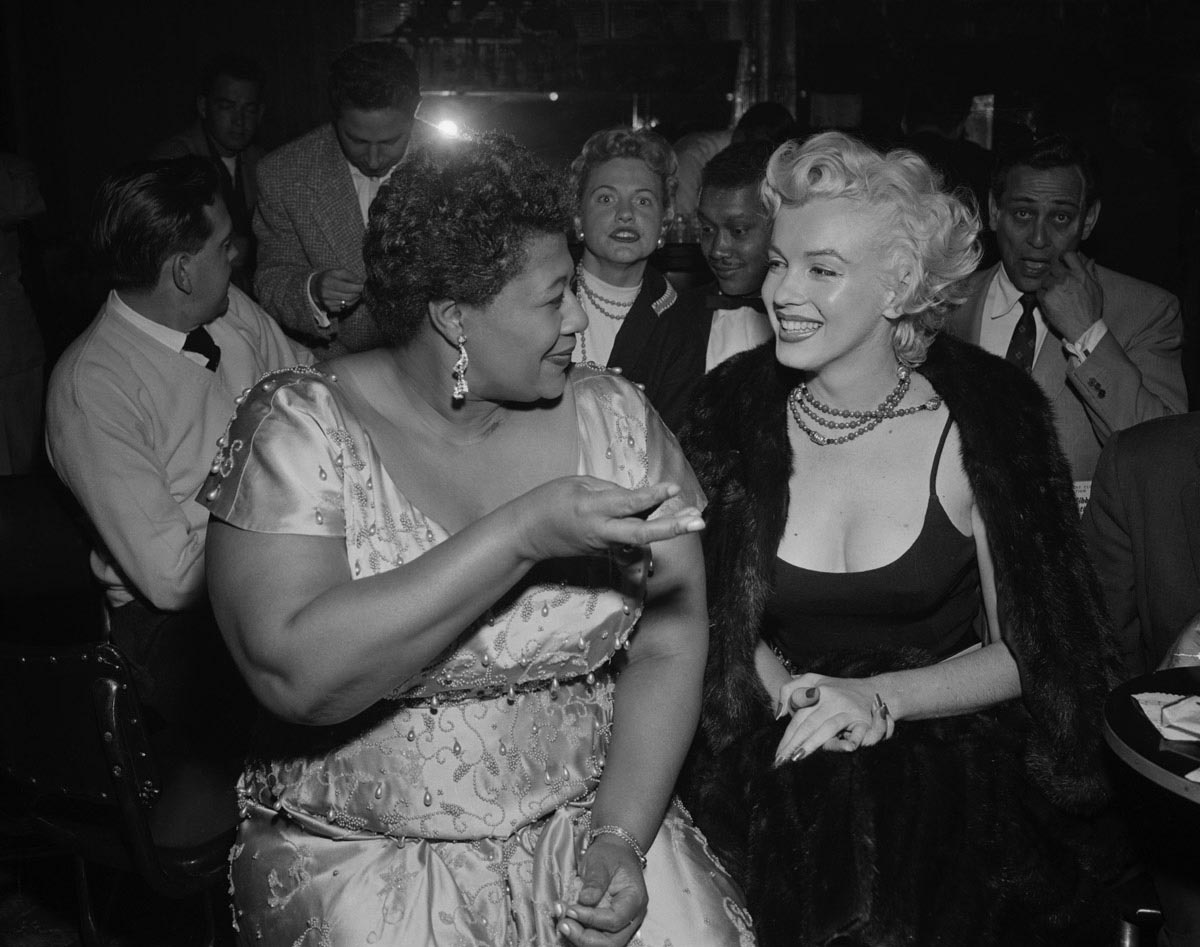

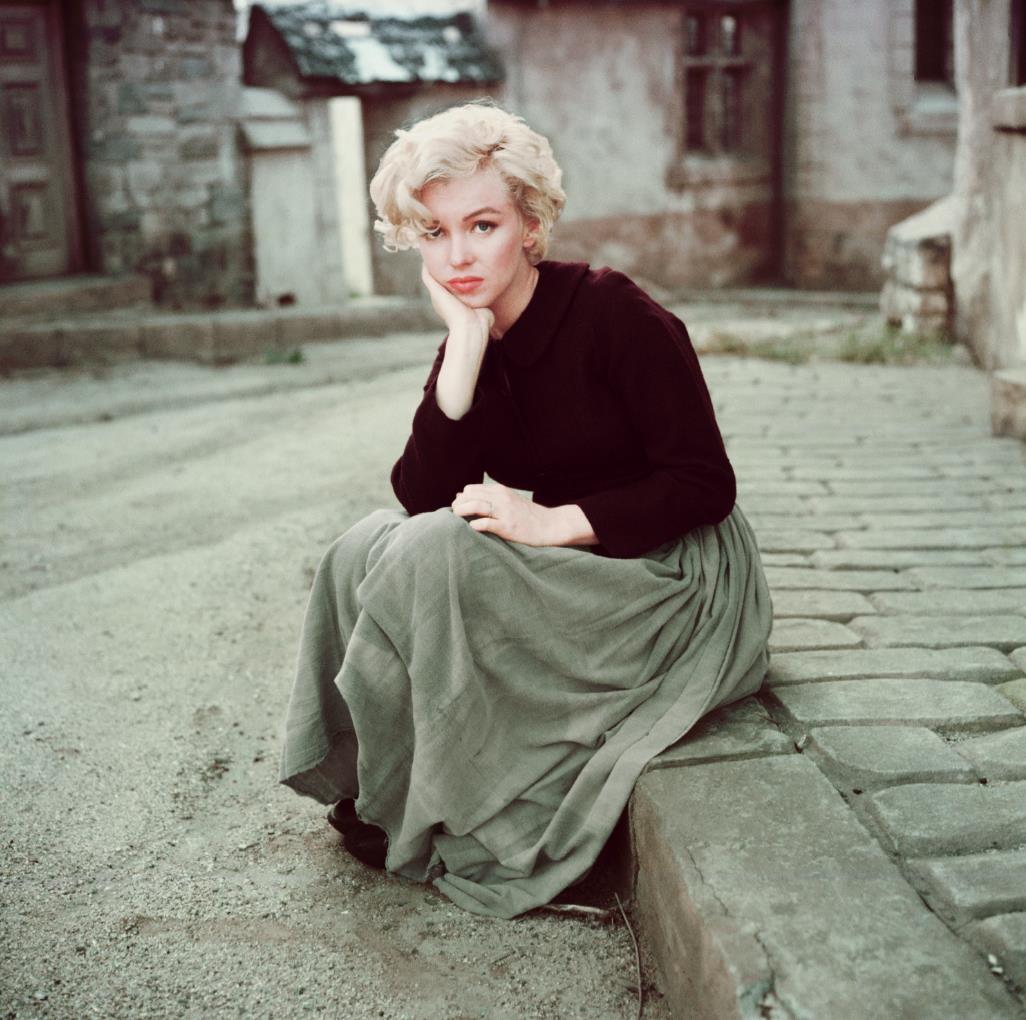

In Los Angeles, the black music scene on Central Avenue was moving to venues on Western Avenue, closer to the center of the entertainment world in Hollywood, and became further de-Centralized as more and more upscale clubs started booking black artists. In November of 1954, due to the personal intervention of Marilyn Monroe, Ella Fitzgerald became the first black artist to play the Mocambo, The Strip’s swankiest joint.

The national charts were dominated by smooth-voiced crooners and vocal groups, whose dreamy blandness diverted attention from the drastic changes for American popular music gathering momentum just over the horizon.

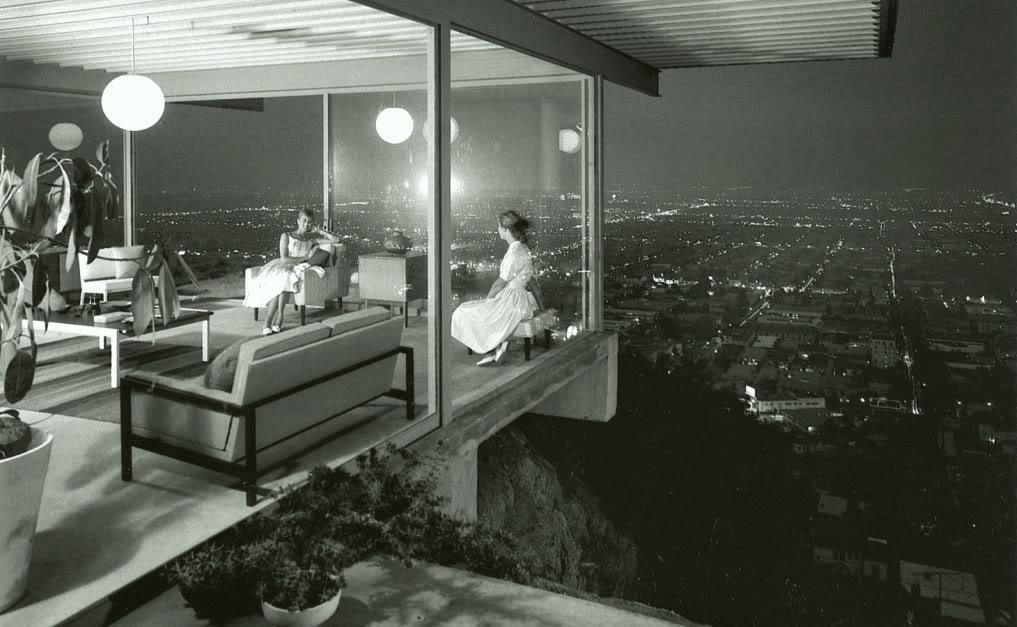

Revolution was in the air. Sinatra’s move from conventional crooner to subtle vocal dramatist, Fitzgerald’s move from pyrotechnical scatting to elegant interpretation, were just as startling in their way as the emergence of rock and roll. Much of the revolution in progress played out in the clubs and recording studios of Los Angeles, where the tensions of the time made the musical scene alive with electric energy, vibrant with possibility.