. . . how can it be? You wanted all of them rounders . . . you never had time for me.

“Delia” is one of the earliest blues songs of which we have any record, dating to around 1910. It was based on a real incident in Savannah in 1900 in which a fifteen year-old youth, Moses “Cooney” Houston, shot and killed his fourteen year-old girlfriend, Delia Green, for dissing and cursing him. He was convicted of murder but, because of his age, given a life sentence instead of the death penalty.

The song proceeded down through the years in a multitude of variants, and is associated with several other murder-ballad blues, notably “Frankie and Johnny” and its respective variants.

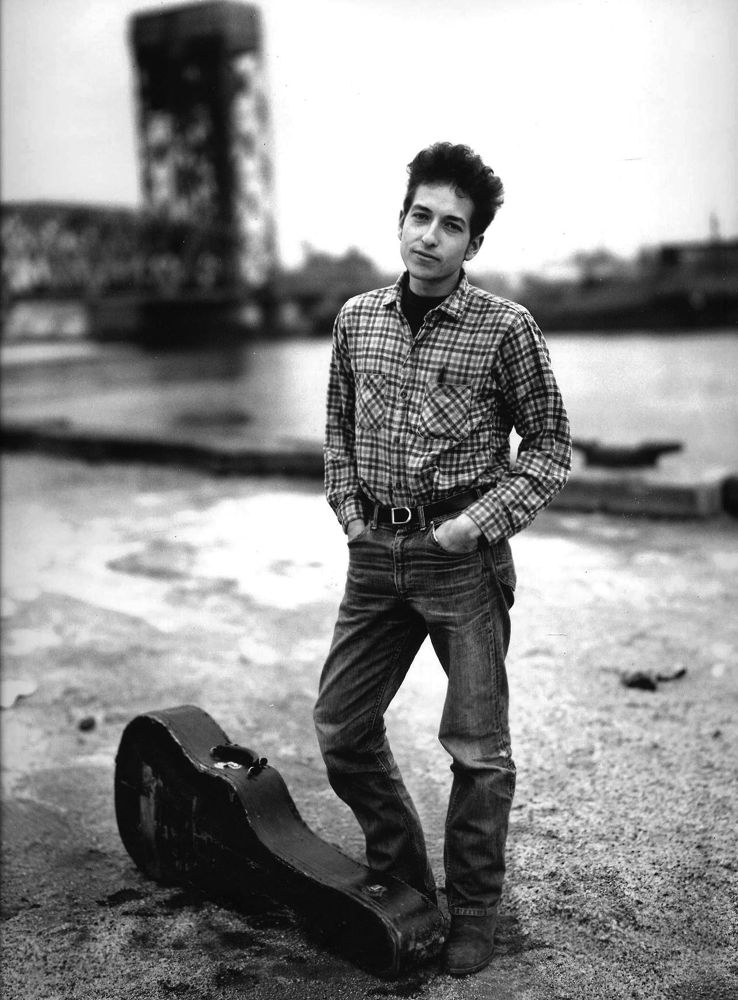

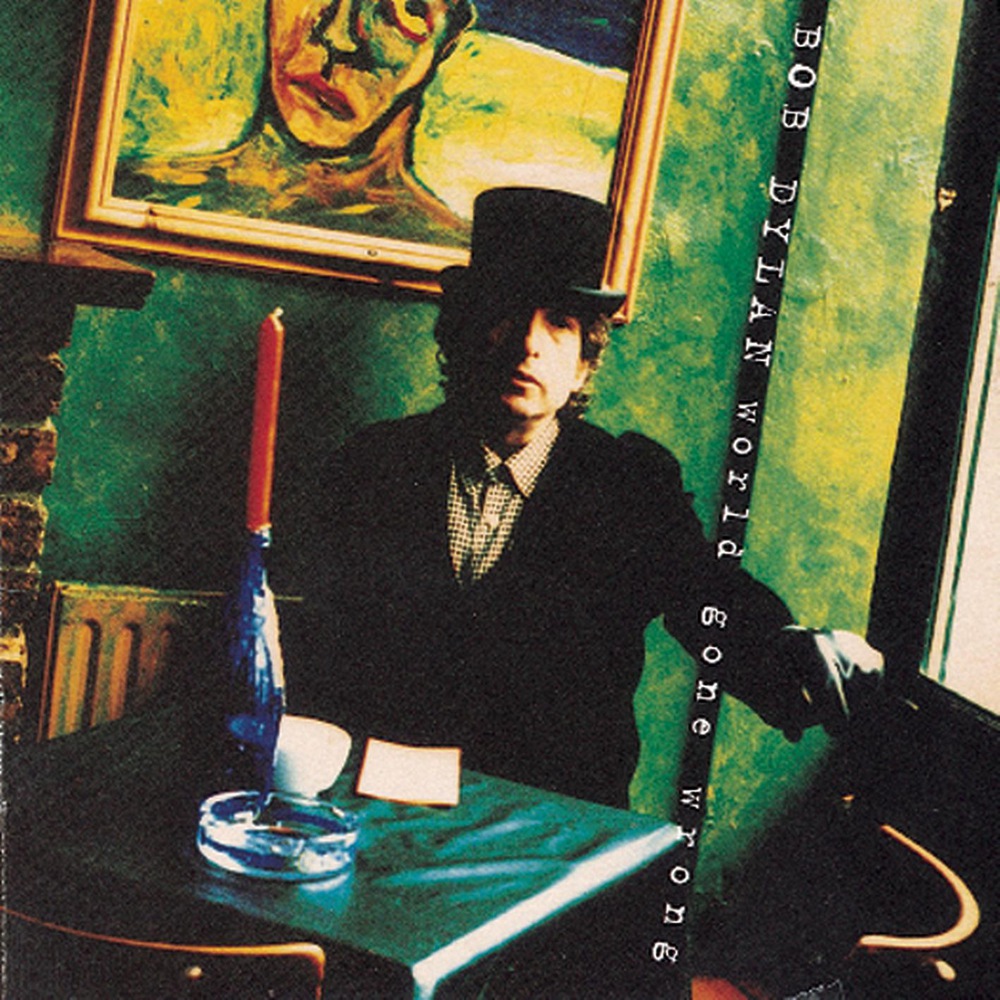

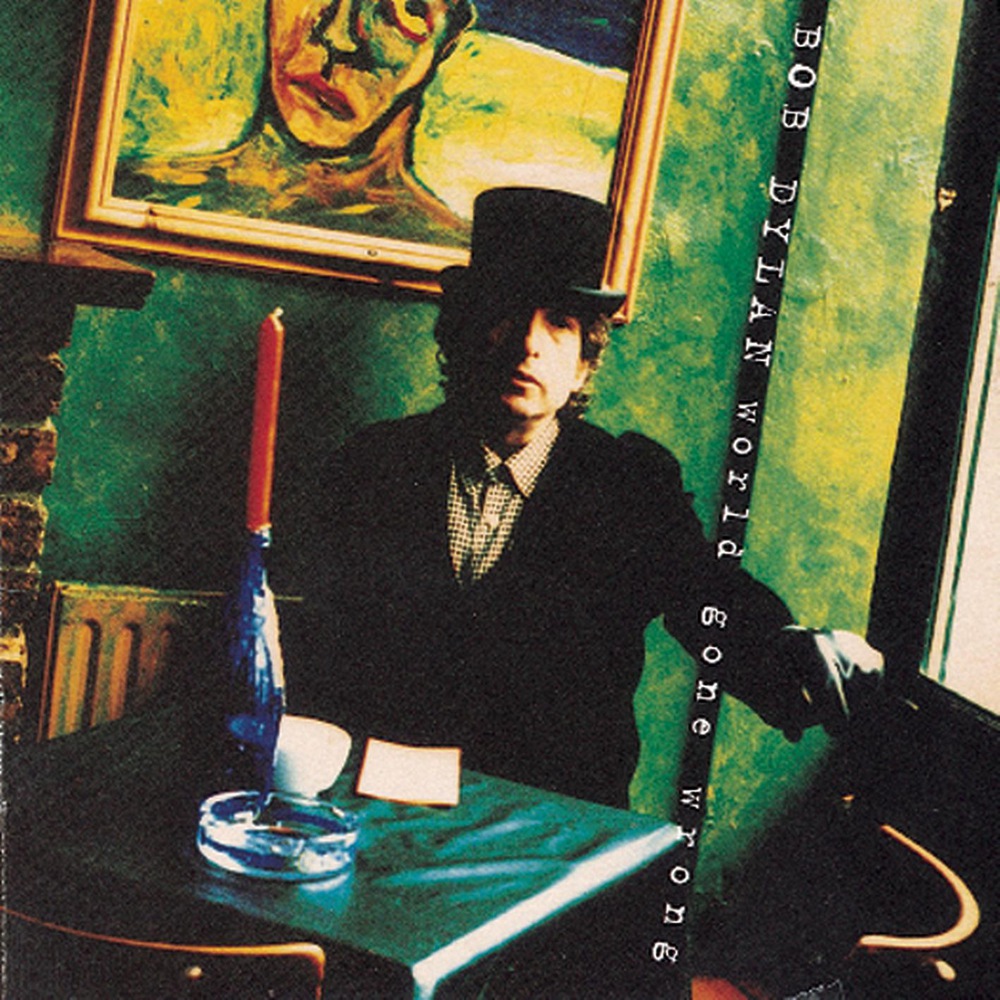

In 1993 Bob Dylan recorded a version of the song for his album World Gone Wrong, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar. According to Sean Wilentz, Dylan based his version on David Bromberg’s, from 1971, but he made some crucial changes to it.

Most importantly, he changed the traditional line that punctuated the verses — “She’s all I’ve got is gone” — to “All the friends I ever had are gone.” The traditional line suggested that it was the convicted youth — identified in different versions as Cooney or Curtis or Cutty — singing the song from his prison cell, though sometimes referring to himself in the third person. It also suggested that the heartbreaking lines at the end, addressed to the departed Delia, also belonged to the youth who killed her — “Delia, oh Delia, how can it be? You loved all of them rounders . . . you never did love me.”

But the change Dylan made — “All the friends I ever had are gone” — suggests something quite different, that the song is being sung by a third person, who loved Delia and was friends with Curtis, and now has lost them both, one to the graveyard and one to a life sentence in prison.

[Delia Green is buried in Laurel Grove Cemetery in Savannah, above, in a location now unknown.]

Whatever Curtis’s dispute with the “rounders, trying to cut me out”, whatever his dispute with Delia, a gambling girl, and thus a rounder herself — whatever led to Delia’s death — is not important to the singer of the song . .. . was not any of his doing. What’s important is that Delia’s attraction to the rounders and to Curtis, her rejection of the singer’s love, have led to nothing but disaster, for all concerned.

“It could have been so different,” the singer seems to say, “if only you’d loved me as much as I loved you.” And now it’s all just a harrowing mystery (how can it be?) in a world gone horribly wrong.

This represents a radical reworking of the narrative and meaning of the song, related to other songs Dylan would write later, particularly “Red River Shore”, in which the singer looks back on a life haunted by a girl who, like Delia, wouldn’t accept his love.

Wilentz, who writes admiringly about “Delia” in his book Bob Dylan In America, totally misses what Dylan has done with the song, a revision that helps explain why Dylan sings it with such wrenching emotion, with the urgency of a heartache that is almost unbearable. He’s not talking about a tragedy that happened to two friends of his but about his own tragedy, a tragedy of missed connections, of unrequited love, of inexplicable loss and unrelieved longing — themes that would inflect much of Dylan’s original work in the years after World Gone Wrong.