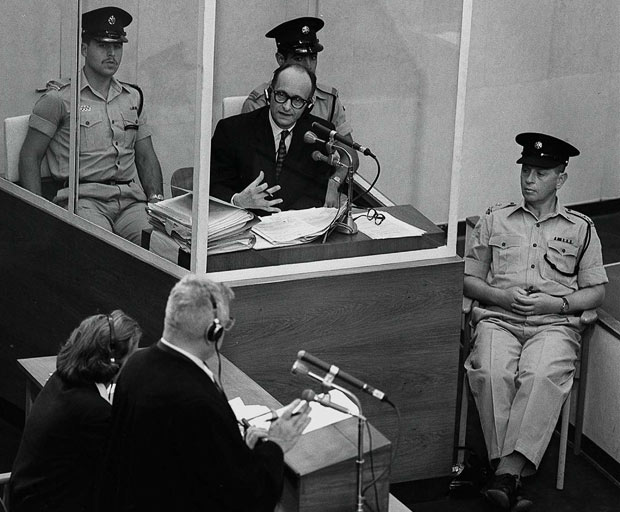

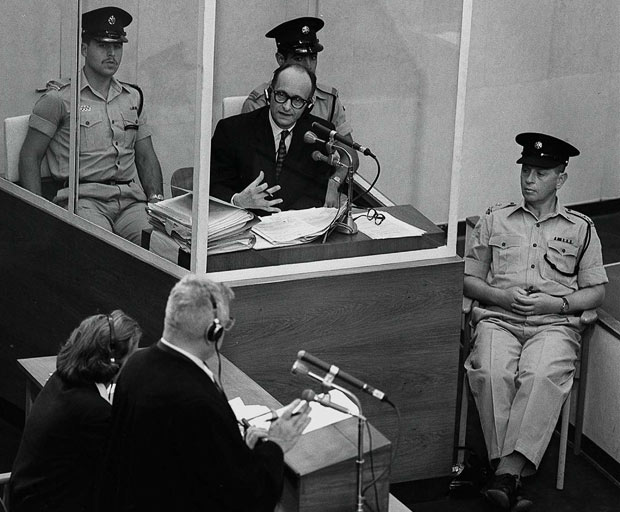

Adolf Eichmann’s 1961 trial in Jerusalem for war crimes was captured on video in its entirety. It was broadcast live within the trial venue for reporters who couldn’t be accommodated in the main courtroom, which had been remodeled from the auditorium of a community center.

It was recorded simultaneously on videotape and made immediately available to broadcasters around the world. Almost all of these recordings are now available on YouTube, and I’ve been watching them — have gotten through about 30 hours of the tapes so far.

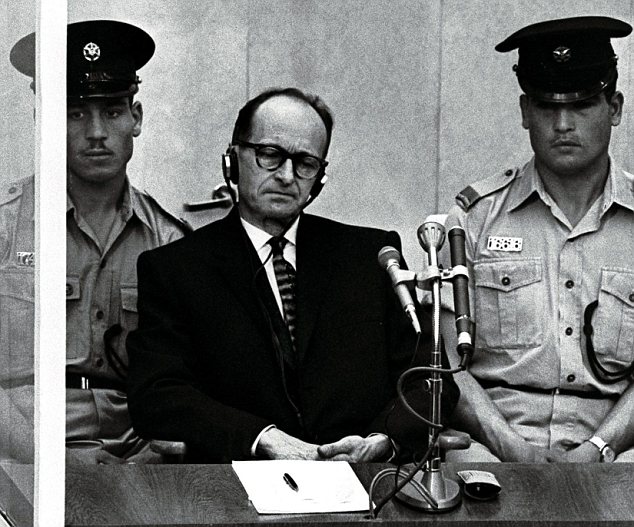

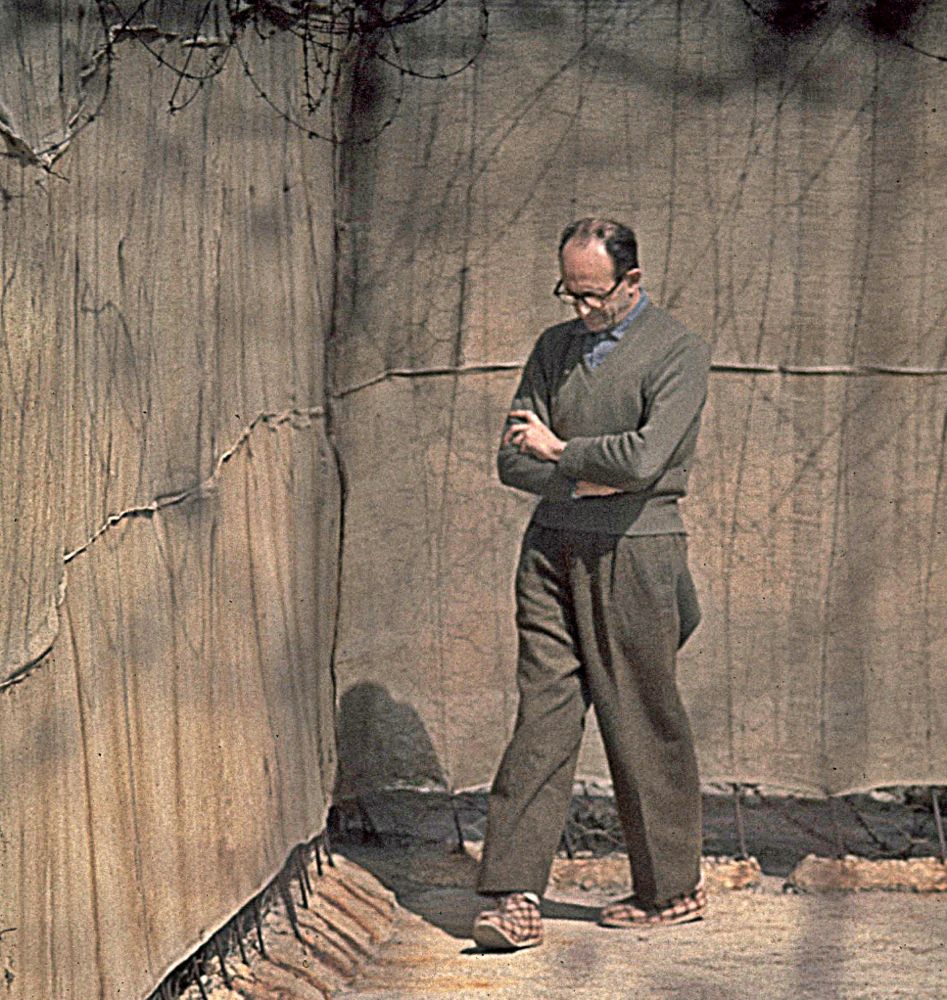

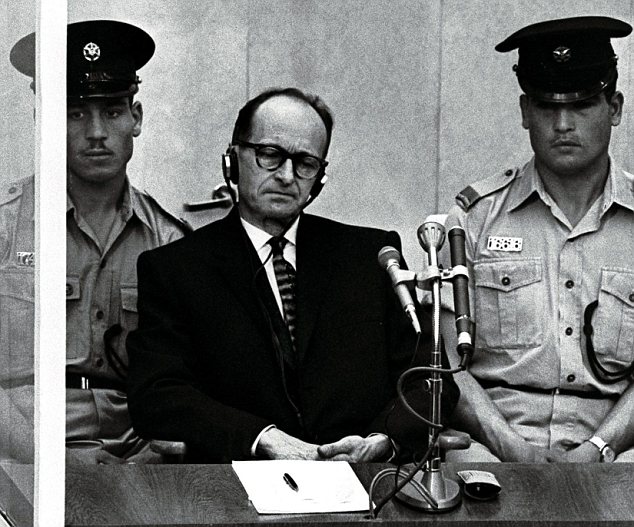

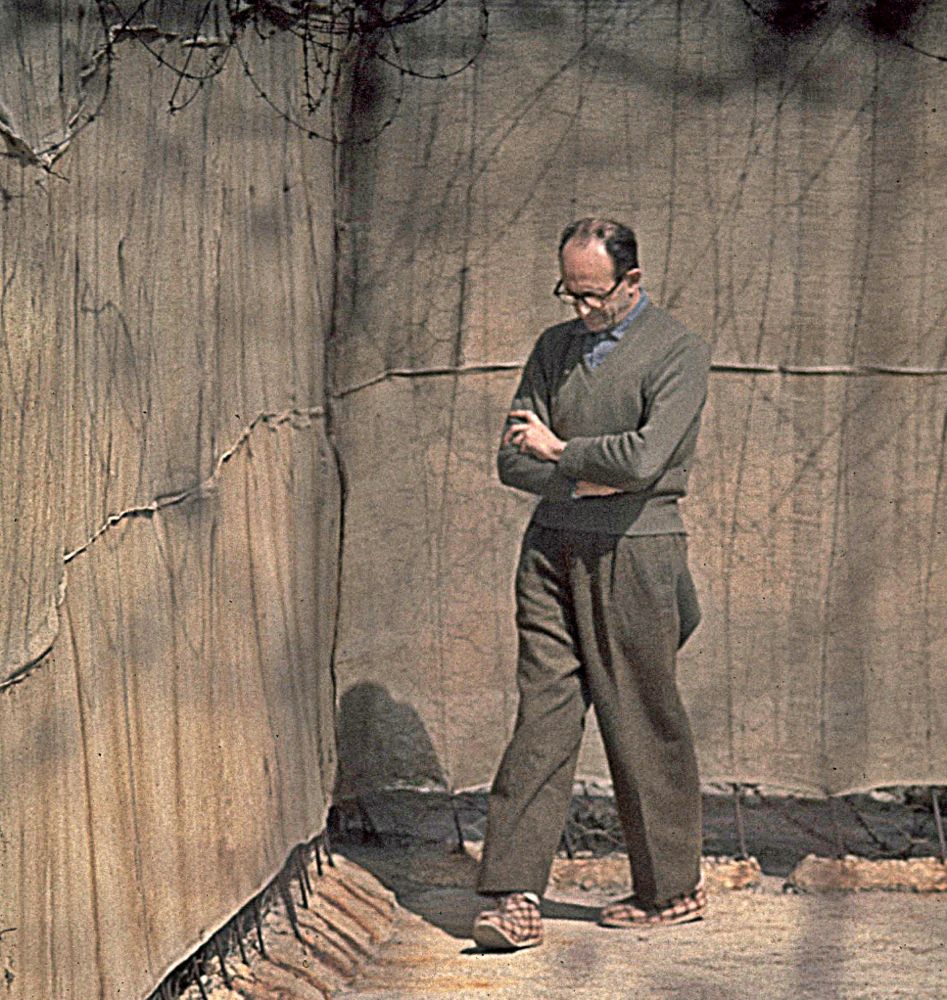

Eichmann was placed in a bullet-proof glass booth, for his own protection, and sat impassively through the testimony of witnesses, mostly Holocaust survivors describing their fate in the system of relocation and murder which Eichmann, as a high-level SS bureaucrat, had played a central role in organizing.

He did not look frightened, or regretful, or sympathetic to the survivors. He had a curious expression most of the time, which might be described as one of mild annoyance or distaste. Of course it’s tempting to try and analyze this attitude.

It may have been that he felt annoyance and distaste at being surrounded by and in the power of so many Jews, which to him would have been a perversion of the “natural” social order. It may have been that he was offended by the messiness of the violence suffered by so many of the survivors. Eichmann enthusiastically supported the liquidation of the Jews of Europe, but he had the soul of a German bureaucrat — he wanted the process carried out efficiently and “correctly”, with as little overt violence as possible.

As I’ve watched the videos, only once so far have I seen Eichmann’s expression change. It was during the testimony of a stern and dignified rabbi’s wife as she told of being smuggled out of Norway with her children in a truck carrying potatoes. The driver, hiding her and the children in the back of the truck, said, “You must not move or make a sound. You must become potatoes.”

Eichmann smiled, in spite of himself, when she said this. (She was speaking in German, so he did not have to use his headphones for a translation.) If you could disregard the context, it was amusing to hear this stern and dignified woman describe being told to become a potato. Perhaps, too, Eichmann liked the idea of one of this accusers being turned into a potato. It is, after all, an image of a process that Eichmann seems to have enjoyed taking part in — turning human beings into inanimate organic matter.

But who knows?