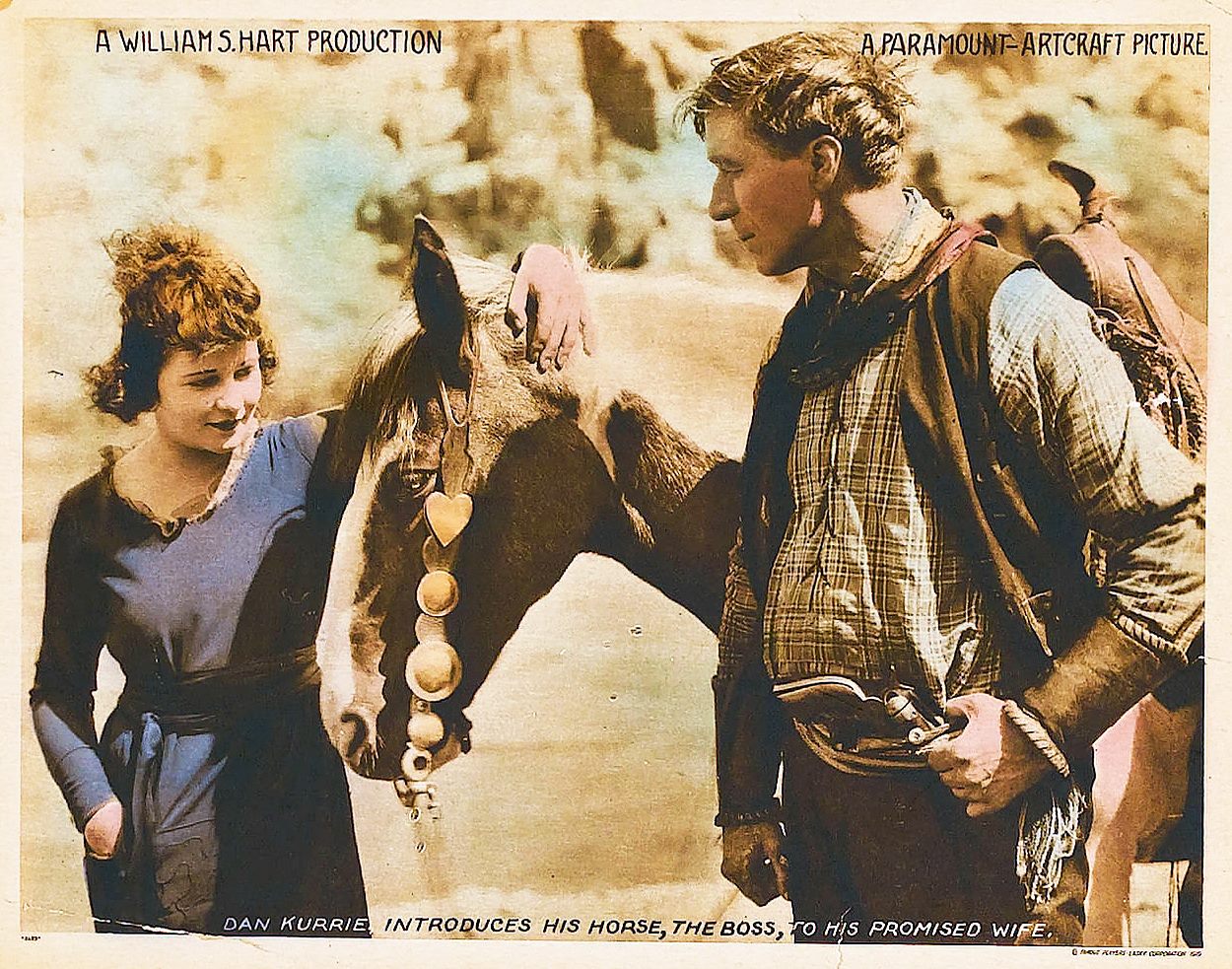

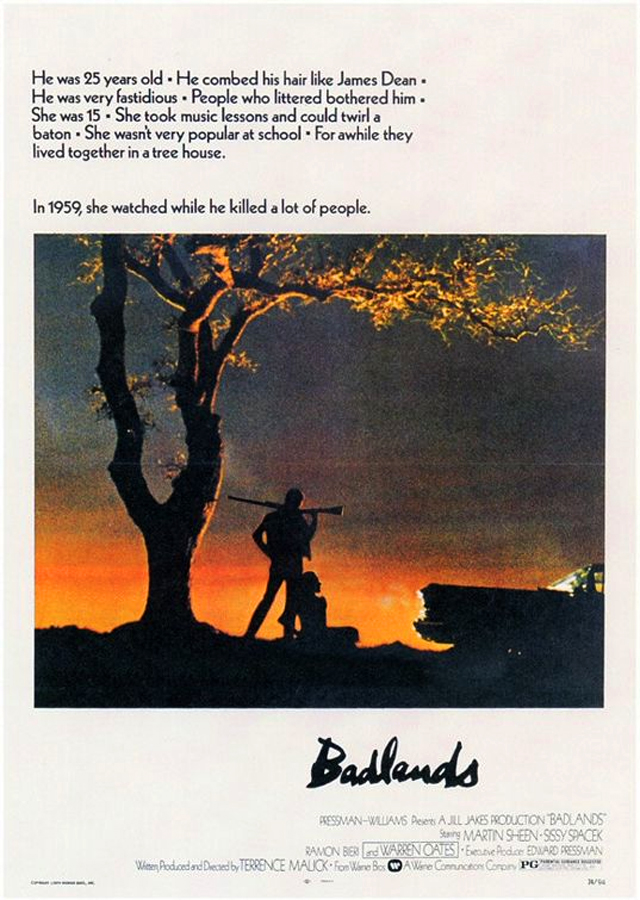

When Terrence Malick’s first film Badlands came out in 1974, Pauline Kael wrote a withering critique of it, finding it to be so self-consciously arty and metaphorical, so “preconceived”, as she put it, “that there’s nothing left to respond to”. It’s a fair comment, as far as it goes, but it doesn’t really go far enough.

Malick was a protegé of Arthur Penn, and Badlands is in some ways a gloss on Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, a film Kael loved and helped to find an audience. Jay Cocks summed up the difference between the two films well. Badlands, he said, “might better be regarded less as a companion piece to Bonnie and Clyde than as an elaboration and reply. It is not loose and high-spirited. All its comedy has a frosty irony, and its violence, instead of being brutally balletic, is executed with a dry, remorseless drive.”

In other words, Badlands is a story about serial killers without the fun and visceral energy of a superior Hollywood entertainment, elements Kael valued highly, and rightly, in cinema. But a film doesn’t automatically descend into what Kael called “draggy art” just because it’s meditative and emotionally cool.

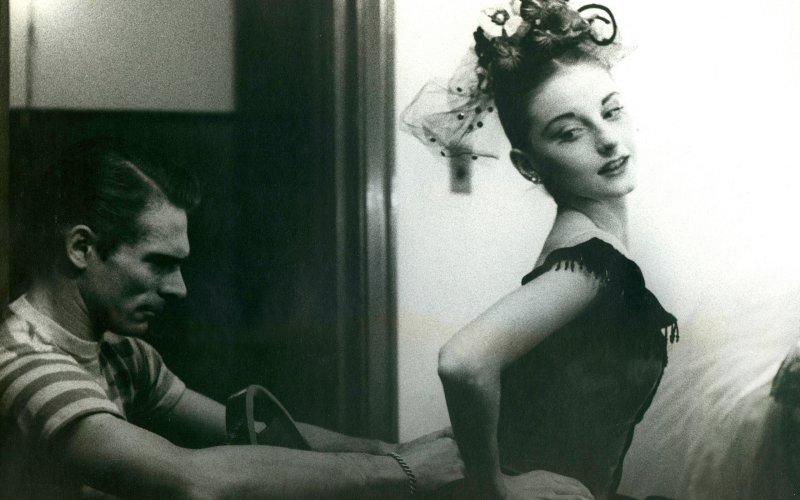

Kael said she found the “cold detachment” of Badlands offensive, but cold detachment is not the only element of the film. Indeed, Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek are such appealing screen presences, and their dialogue is so funny, that the film starts out warm and engaging. It’s only as the narrative proceeds that Malick asks us to take a step back from them, to see them as stupid and evil — to see the charm of Sheen’s Kit as repellent.

Malick wanted to play with our expectations about films of youthful rebellion, to make us slowly but surely self-conscious, even a bit ashamed, of those expectations. It’s a somewhat cerebral approach to filmmaking, perhaps, but not necessarily pretentious. Hitchcock made grand popular entertainments out of the same ambition to undermine our identification with his protagonists, keep the ground of expectation and sympathy shifting beneath our feet.

I would also argue that the film is not quite the metaphor for modern American society that Kael and others have seen it as. Kael said, “The movie can be summed up: mass-culture banality is killing our souls and making everybody affectless.” It can be read that way, I guess, but it seems to me that Malick wasn’t trying to be so dogmatic, so obvious.

Although Sheen has the active and showy part, the film is really about Spacek’s Holly. She’s the narrator of the film, and there are suggestions that she may not be a reliable narrator. Towards the end of the film she recounts an event she wasn’t present at, tells us what she thinks might have happened, and Malick shows it happening that way on screen.

It makes us wonder, in retrospect, how much of the story Holly’s been telling us is really true and how much reflects her adolescent fantasies of how it might have been or should have been. It’s yet another way of Malick distancing us from the story, but it also invites us to move closer to Holly, to try and get inside her head, and this is really quite far from the “cold detachment” that Kael accuses Malick of.

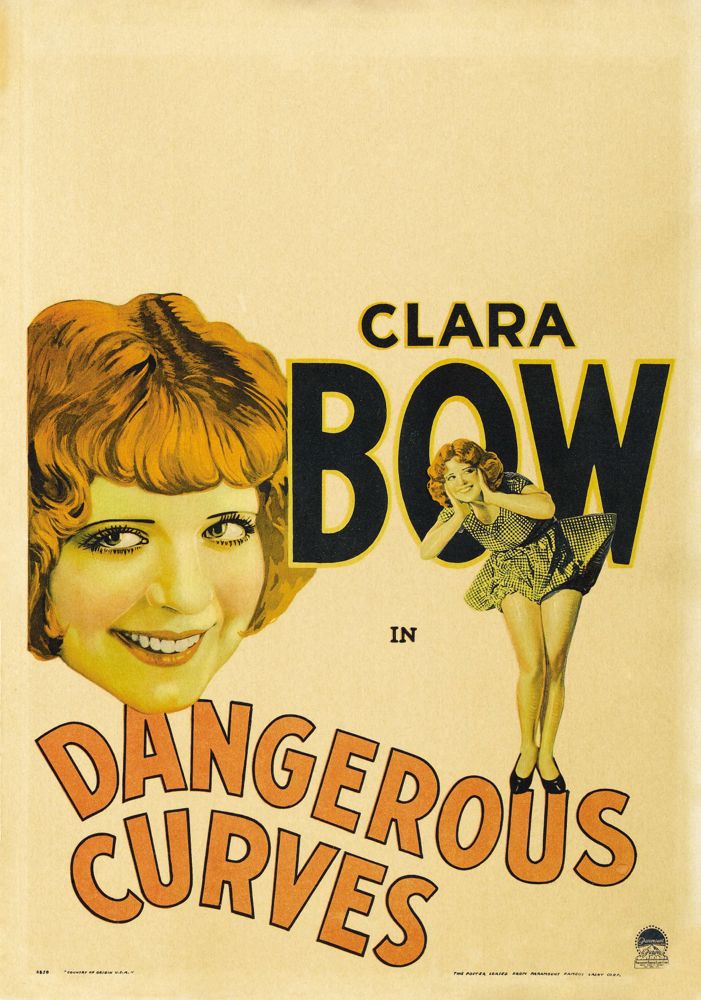

And though Holly reads celebrity gossip magazines, she’s also fascinated by antique stereographic pictures she’s brought from her home. She reads from Kon-Tiki, a popular book, but one that was ten years old at the time the movie is set and not an artifact of teen culture. Her head is filled with fairy tales and dreams of adventure as much as it is with images derived from romance comic books.

It’s Kit who sees himself as James Dean and spouts platitudes that seem to be lifted from The Reader’s Digest. He represents the banality of mass culture, but Holly wants to see him as something finer and more romantic. You begin to doubt, when you think about it, if Kit and Holly’s dreamlike idyll in the forest ever happened at all — to suspect it might just be something Holly made up out of images from Swiss Family Robinson.

Kael was right to note that there’s something overly calculated about the film, but wrong to see that calculation as simpleminded. I think Malick had subtler and deeper ambitions for the film than creating metaphors about modern society. He had begun, haltingly and vaguely perhaps, his investigation of the imagination’s role, love’s role, the beauty of nature’s role, in reconciling us to life — even a life as bleak and hopeless as Holly’s.