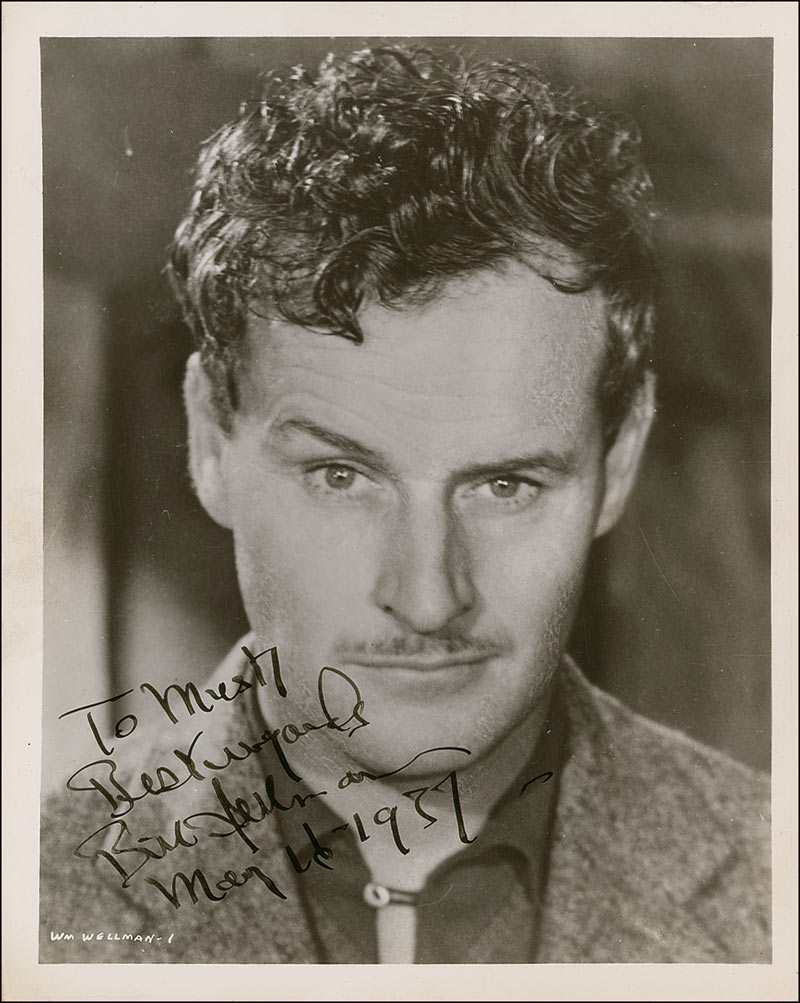

A lot of Hollywood directors who earned their spurs in the silent era and survived into the sound era had backgrounds far removed from the picture business. A number of them were mechanics, race car drivers, pilots. They were what used to be called manly men, and they brought a traditional masculine perspective to their work in action films. I’m talking about guys like William Wellman, Howard Hawks and Victor Fleming.

Curiously, these men were also exceptionally skilled in presenting strong women on screen — they seemed to be fascinated and not in the least bit threatened by strong women. Victor Fleming, who directed Gone With the Wind and The Wizard Of Oz, both anchored by strong female leads, was also the first director to let Clara Bow do her thing on screen in the silent film Mantrap, in which she ran sexual circles around her male leads and laughed at them while she was doing it.

Hawks unleashed Hildy Johnson and Sugarpuss O’Shea and Lorelei Lee on equally defenseless males and made us laugh at their invincible power and wit.

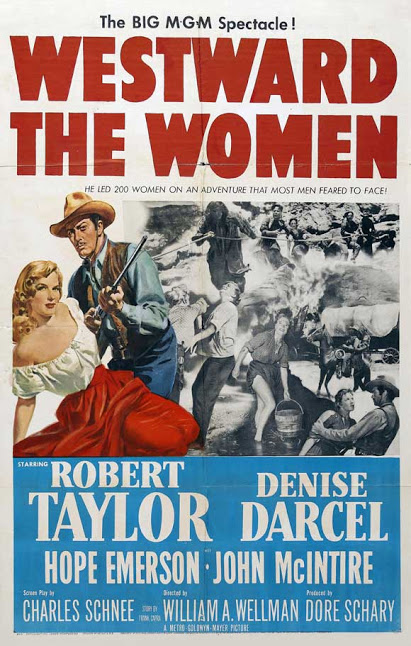

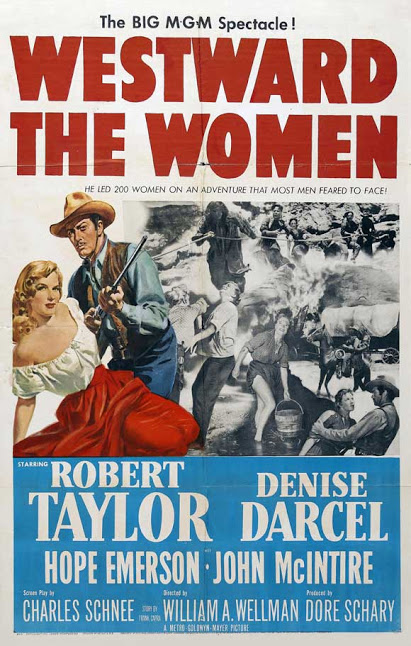

In 1951 William Wellman made the very odd Western Westward the Women about a wagon train of mail order brides making a 2000-mile trek from Chicago to California to hook up with prospective mates on the frontier. There are a couple of ex-hookers among them, hoping to turn over a new leaf, but they’re mostly “good women” looking for good husbands.

They’re led by the exceptionally competent but distinctly misogynistic trail guide Buck Wyatt, played by Robert Taylor. He admits up front that only two things in life scare him, and they’re both “good women”. He says he hates women’s cooking, and doesn’t expect much out of his charges except suffering and perseverance. He hires a gang of men to provide for their defense on the journey.

But then most of the men desert the train when Wyatt executes one of them for raping a woman. Wyatt wants to turn back but the women won’t turn back, even if he does. At that moment they become the heroes of the film, and Wyatt watches as they do what needs to be done to get the train through, at first amused, then a little bit awestruck.

The women don’t turn into men. Before they arrive at their destination they insist on stopping so they can make themselves presentable when they meet their future partners. Wyatt doesn’t understand this — it seems a little “girly” after all they’ve been through — but he’s past arguing with them. They’re his equals as trail bosses now.

Yet when the women show up to meet the men they’ve prettied themselves up for, their spokeswoman makes it clear that the women will do the choosing. Their passage across the continent may have been paid for by the men, but the women are in charge of the pairing up — they’ll have the last word on that.

Wellman presents all this with little comment — not making a point of female courage and competence, just showing it. Nor does he patronize the women’s desire to make themselves attractive at the end. He just respects it without judgment — not suggesting that they’ve turned back into “girly girls” but accepting that they’ve always been girly girls, as well as tough characters, as tough as any man. They can work like men, and fight like men, and die like men, but they’re . . . different.

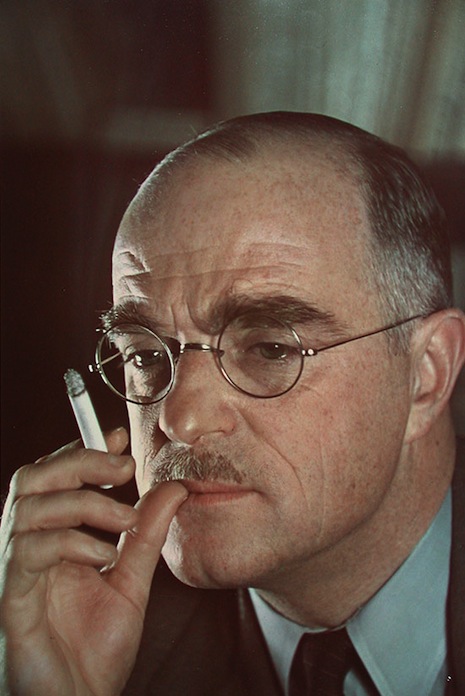

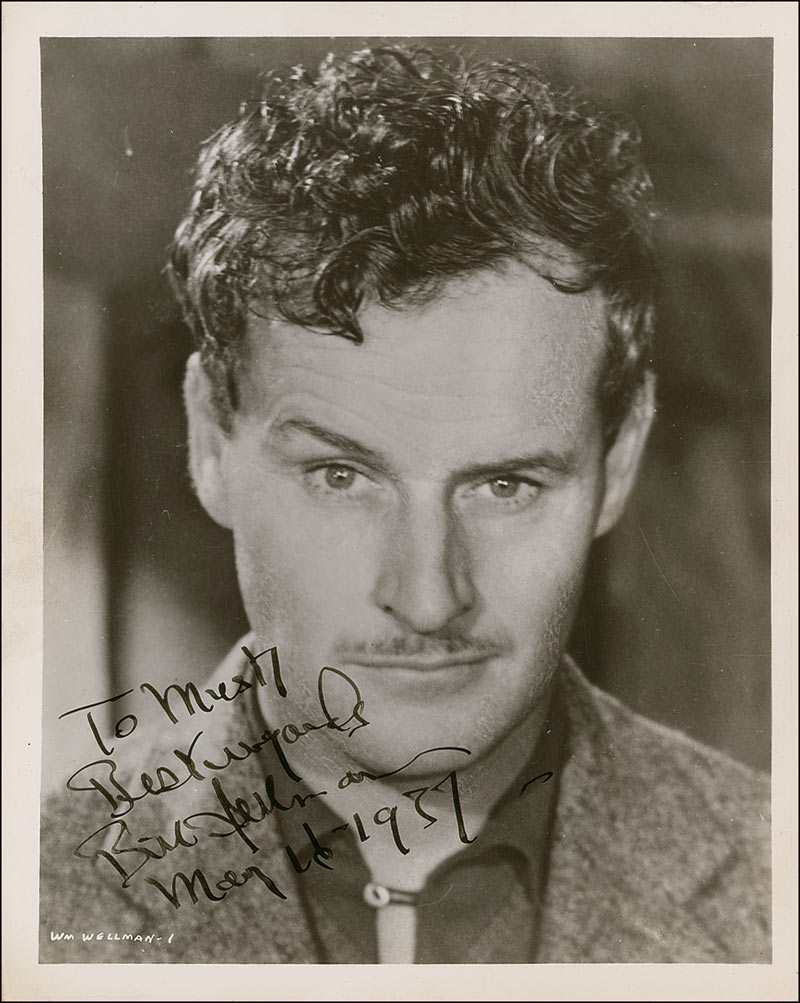

Wellman was a tough guy — he won the Croix de Guerre with two palms flying airplanes in France in WWI. It took a tough man to make a movie like Westward the Women.