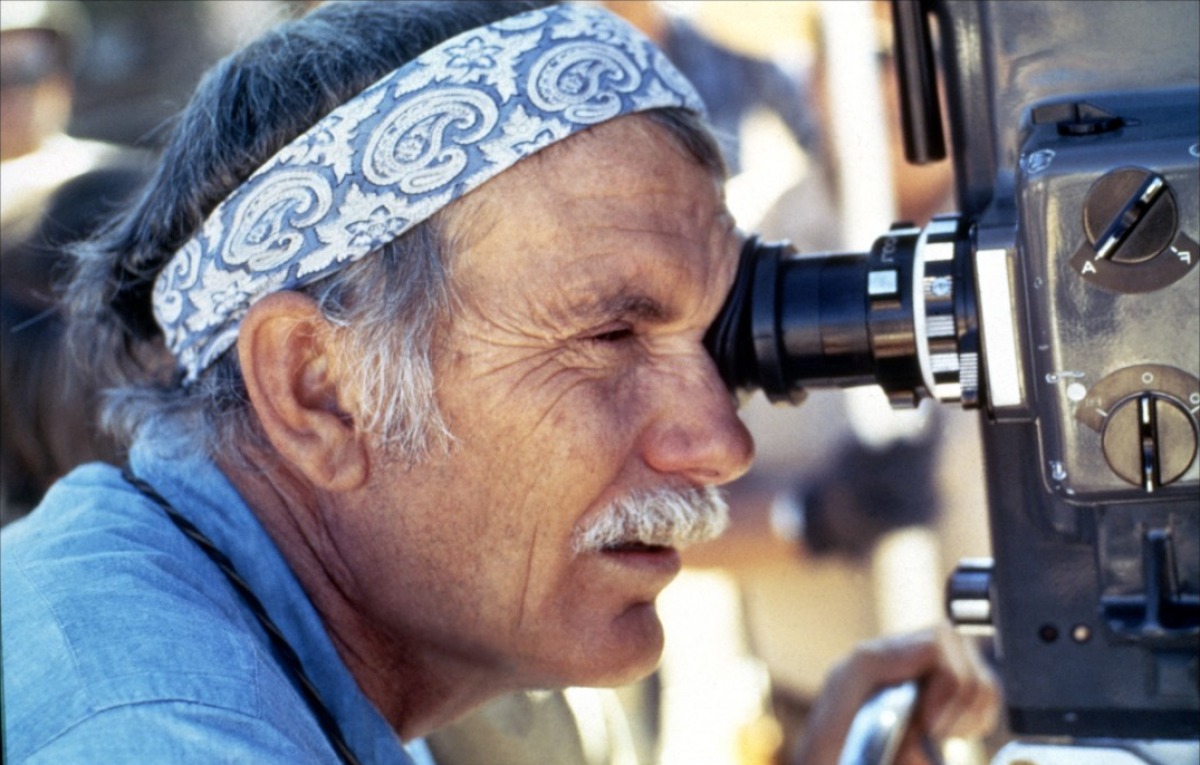

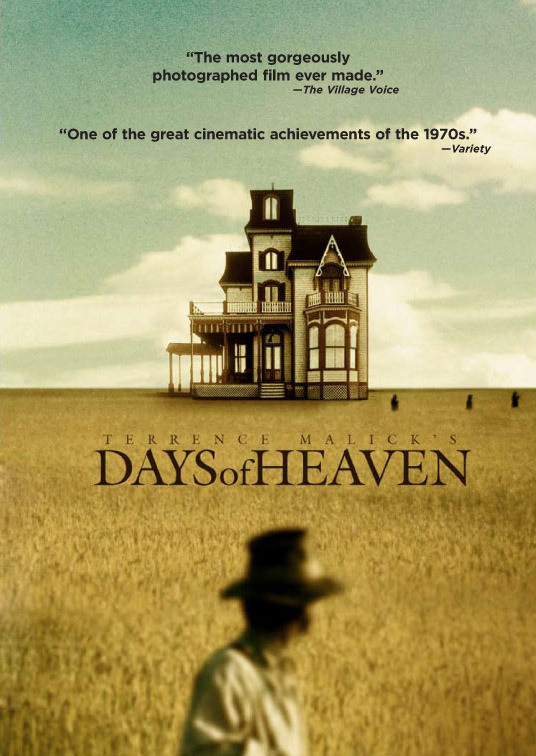

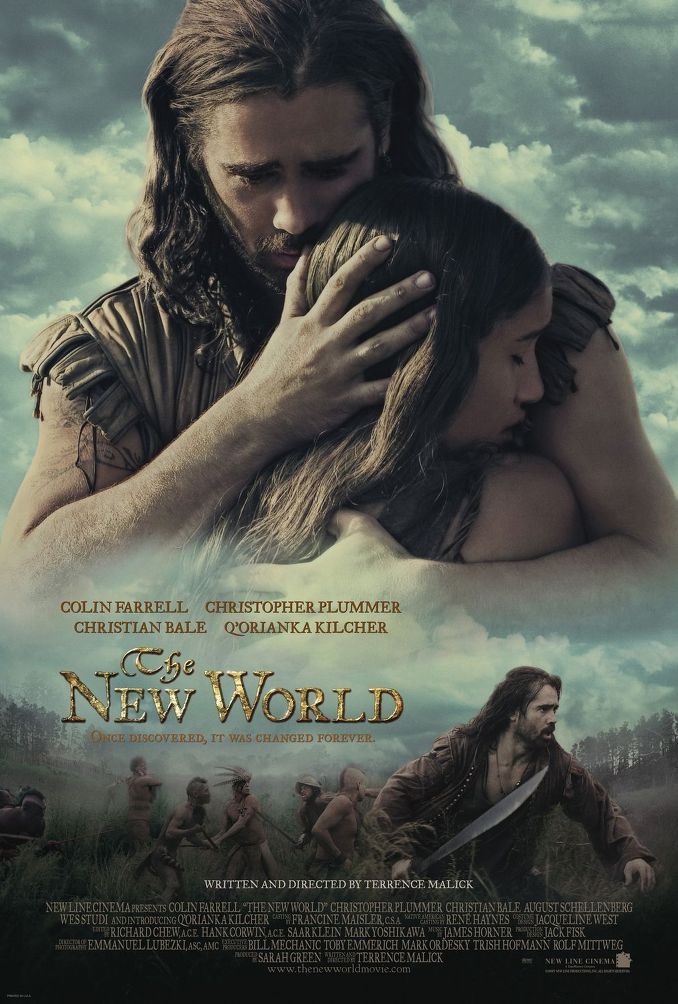

I originally watched this on DVD in the theatrical cut — just recently watched the extended cut on Blu-ray. I had different reactions to each viewing, due perhaps as much to my evolving thoughts about its director Terrence Malick as to the differences between the formats, although those differences are important.

I was somewhat underwhelmed by the film on my first viewing, finding the resolution of the narrative unsatisfying. Since then I’ve come to realize that the narrative Malick hangs his images on is not necessarily the narrative he’s trying to tell, or the narrative he’s most interested in. The images have their own story, or stories, to tell, and these sometimes serve the narrative and sometimes expand it into a new territory.

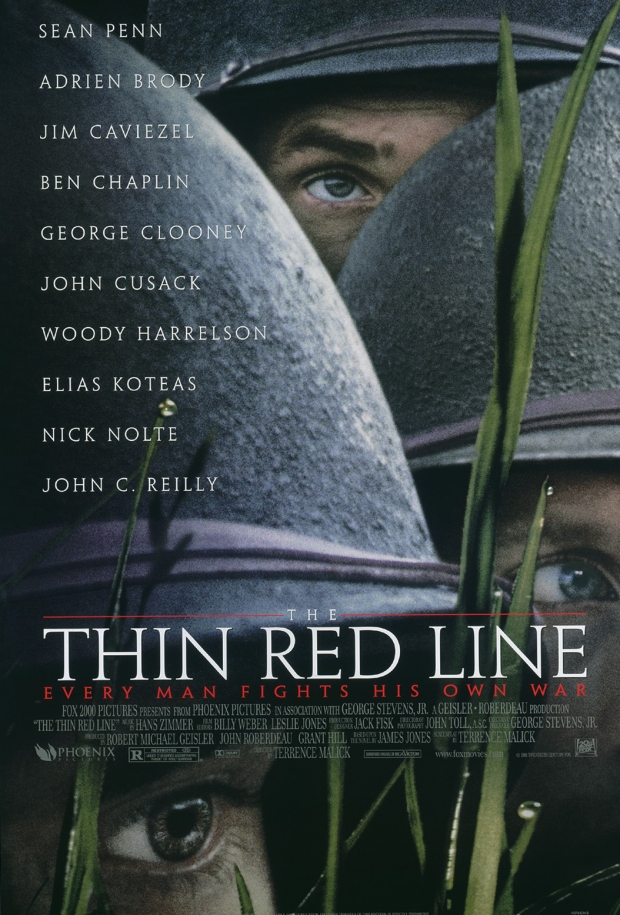

At least since The Thin Red Line, Malick has been concerned with evoking the physical experience of spaces and places as they relate to, and sometimes confound, the literal events of the narrative. The Thin Red Line is, most obviously, a drama about the command problems that beset a company of soldiers fighting on the island of Guadalcanal during WWII, and it works very well on that level. But it’s more centrally concerned with the experience of combat itself — the minute-by-minute, hour-by-hour, day-by-day reality of it. On the first level it’s a good war movie, on the second level it approaches something profound.

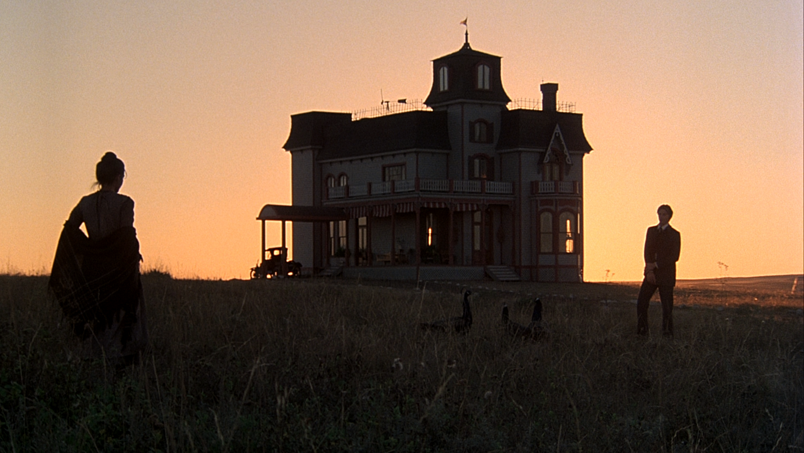

The New World tells the tale of Jamestown, the first permanent English colony in North America, incorporating the familiar (and perhaps apocryphal) story of John Smith’s love affair with a Native-American woman, Pocahontas. Its images, however, move on a far deeper level, in which the strangeness of the landscape and its inhabitants to the Europeans comes to stand for any kind of strangeness in human experience, especially the strangeness of falling in love, the strangeness of second chances.

The fates of the characters in story terms become secondary — what they feel and experience, existentially, become the film’s true subject. One can imagine a much more riveting and economical retelling of the story of Smith and Pocahontas — one cannot imagine a much better film about discovering a new world, about the phenomenon of sexual love.

Malick is not deconstructing narrative here, he’s expanding narrative, in a purely cinematic way. He’s suggesting, for example, to put it as simply as possible, that when you make out with someone on a blanket under the stars, with a light wind blowing, the stars and the wind are not just the setting for an extraordinary event, they’re part of what the event is, as intimate a part as the taste of the kisses themselves.

Since the true subject of The New World is to be found in its images, one has greater access to the whole work on a big screen in a theater than on a TV, and on a big TV screen in the Blu-ray format than on a smaller screen in the DVD format. With anything less than the Blu-ray format on a big TV screen, I’m not sure it’s worth watching a Malick film at all — you certainly won’t have meaningful access to the movie he’s trying to make.

By the same token, the extended cut of The New World, which lingers longer on the landscape and on the people moving through it, is more satisfying than the theatrical cut (about 35 minutes shorter), because it takes you deeper into the visual heart of the film — at least if you can manage to relegate the nominal narrative to the level of a pretext for something much more interesting and involving.

This is the epigraph that opens the extended cut of The New World:

How much they err,

that think every one which has been at Virginia

understands or knows what Virginia is.

— Capt. John Smith

It might as well read:

How much they err,

that think every one which has been in love

understands or knows what love is.

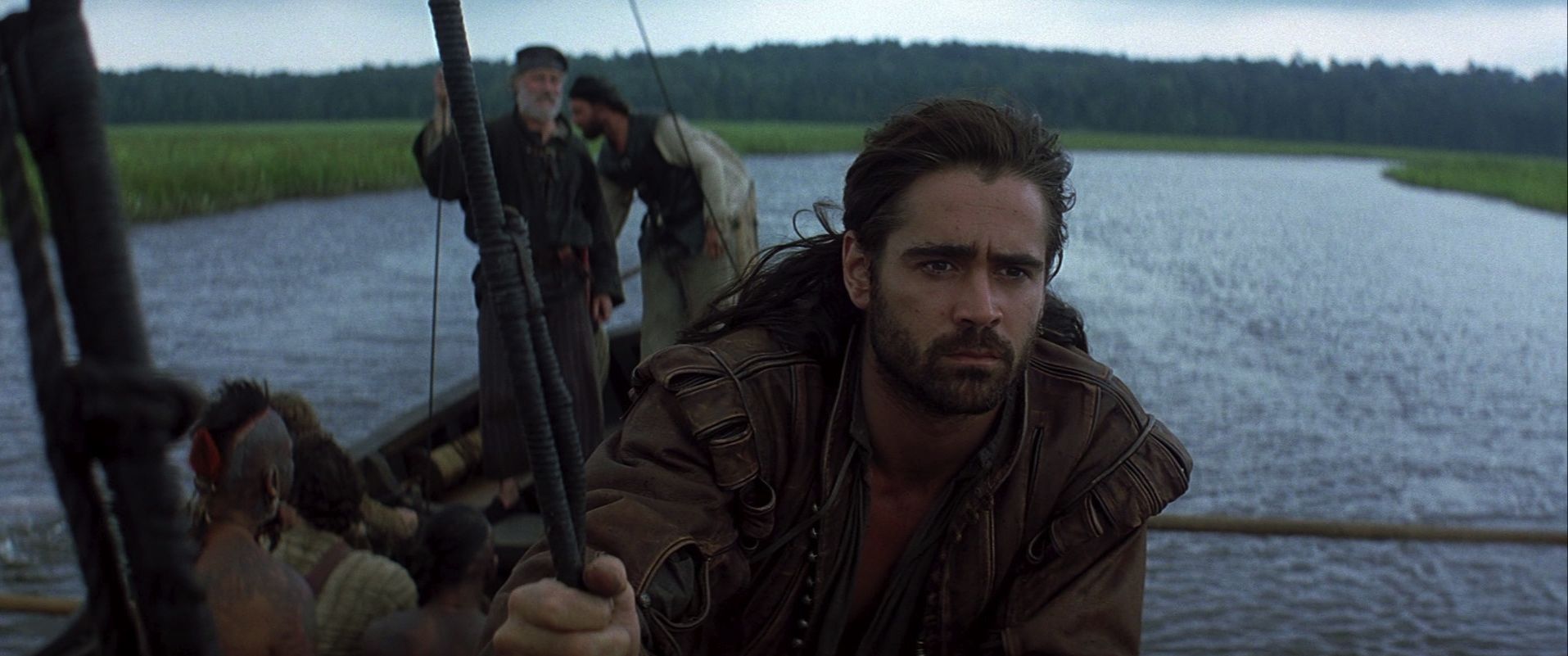

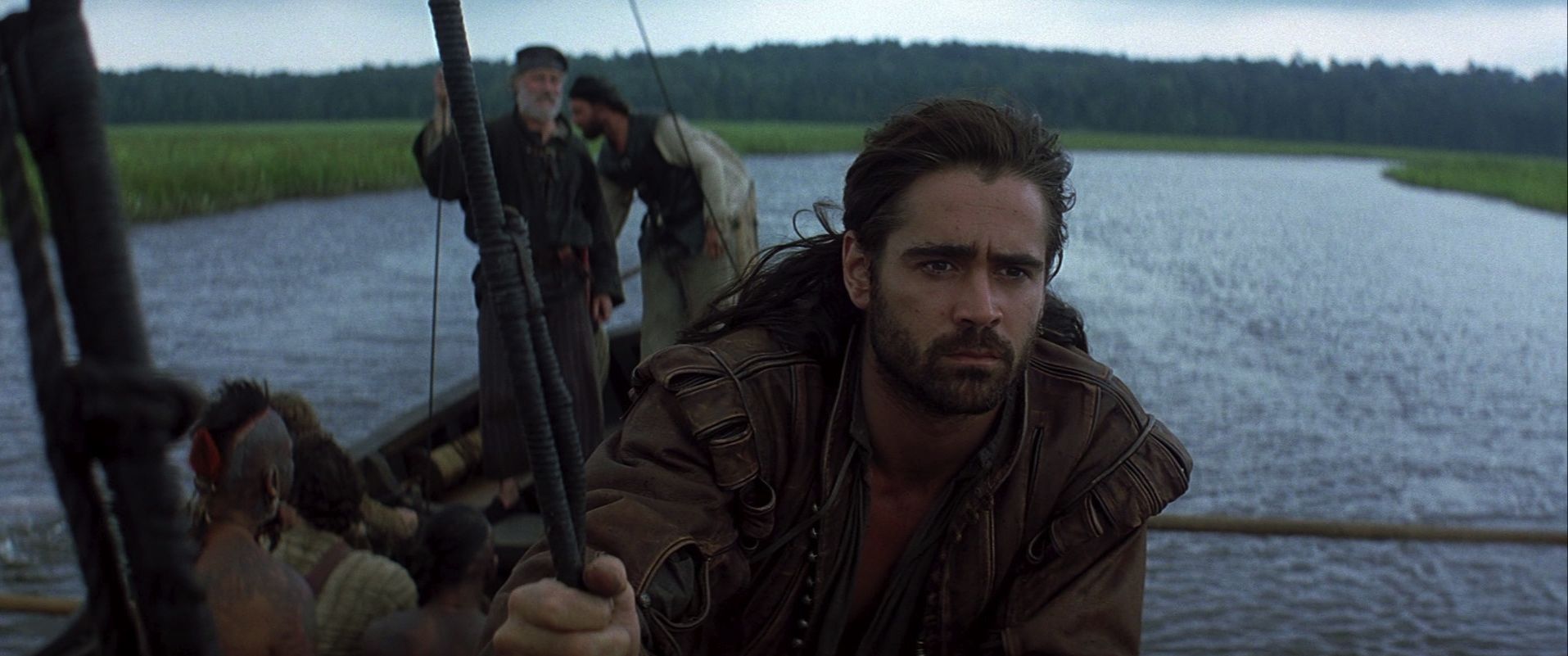

Indeed, the film opens with images of naked women swimming underwater in the river the colonist are sailing up for the first time, with John Smith in chains in one of the ships’ holds, condemned to be hanged. Instead he’s pardoned and given a chance at a new life in this new world. Malick undertakes to show us what Virginia is, what love is, in one of the most ambitious, one of the most original movies ever made. Your response to it will depend a lot on your willingness to sail up unfamiliar rivers and creeks with Smith and Malick, your willingness to take your time looking around you, and your openness to what you find at journey’s end.

The ending of the film made sense to me on the second viewing — if John Smith lost faith in, didn’t value highly enough his second chance in life, Pocahontas did. The “new world” she was born into stayed alive for her — while Smith sailed past his Indies, into oblivion.

Click on the images to enlarge.