Angst in the American suburbs, circa 1955. It’s well-traveled territory in movies but remains an interesting subject, at least to those of us who did time in the American suburbs of the 50s and 60s.

The fascination lies in the contrast between the image of a suburb, peace, security, home ownership and big green yards, far from the mean streets of the city . . . and the reality of a suburb, isolation, loneliness, the absence of social amenities that help create communities.

The suburbs were a creation of post-WWII America, and their soullessness has become a cliché in popular culture. So a film like Sam Mendes’s American Beauty, which lays bare the angst of a modern American suburb, feels like shooting fish in a barrel, like the day before yesterday’s news.

Going back to the era when suburbs were born has at least the virtue of cultural archaeology, a chance to meditate on the social aspirations and anxieties that produced the phenomenon. Mendes’s Revolutionary Road is a respectable meditation on the era of the suburb, on the crude attempts of isolated people to establish community, on the despair that seemed to simmer just beneath the Leave It To Beaver facade.

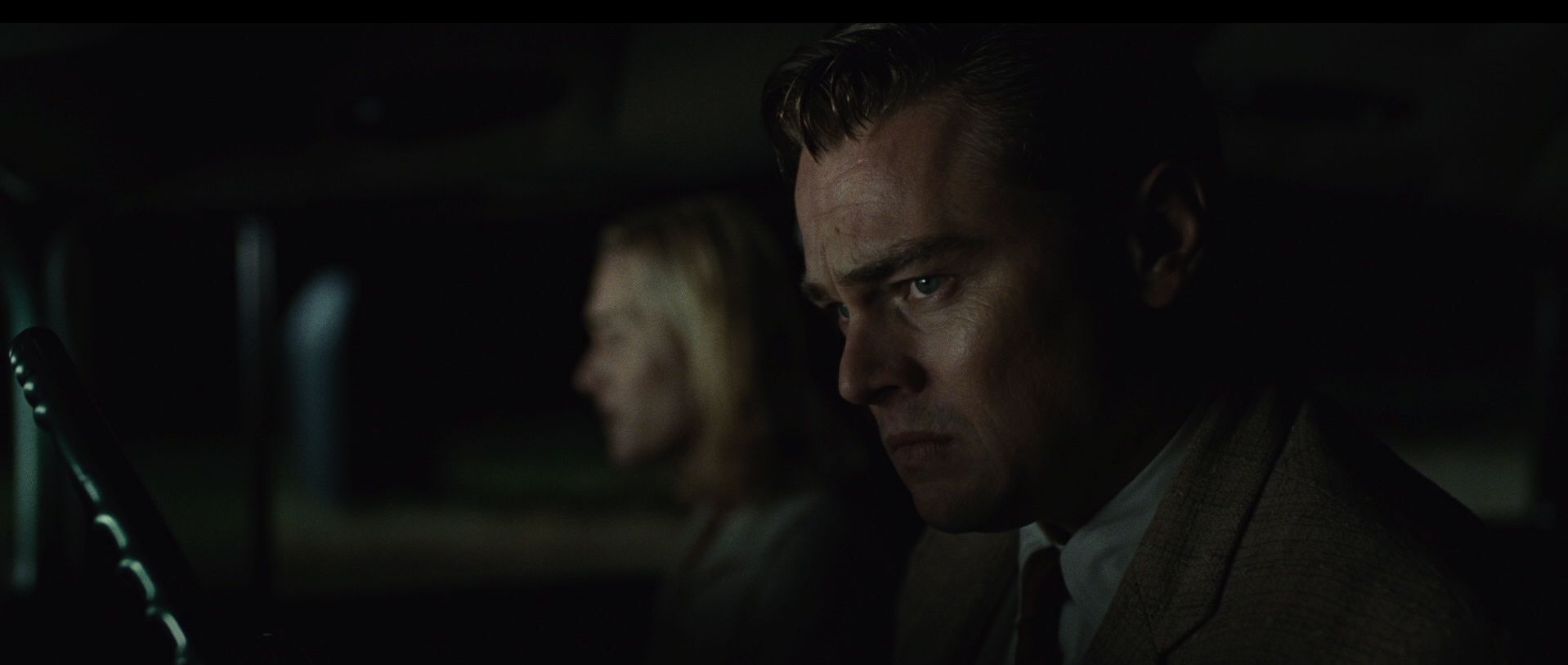

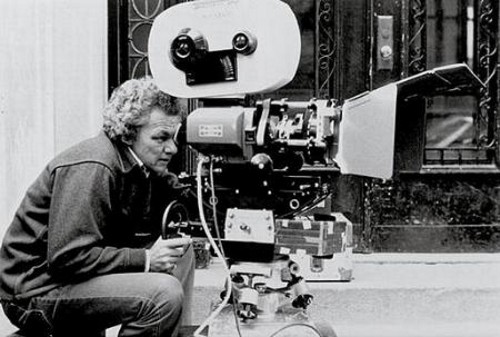

Winslet and DiCaprio give oddly uneven performances, punctuated with moments of genuinely harrowing brilliance. They make you forget entirely that they once played the young lovers of Titanic, which you’d think would be impossible. The film’s greatest asset, however, is the cinematography of Roger Deakins, with its beautifully composed shots and its subtle but expressive lighting. The images draw you in imaginatively, make you feel a part of what is, at bottom, an overly familiar tale.

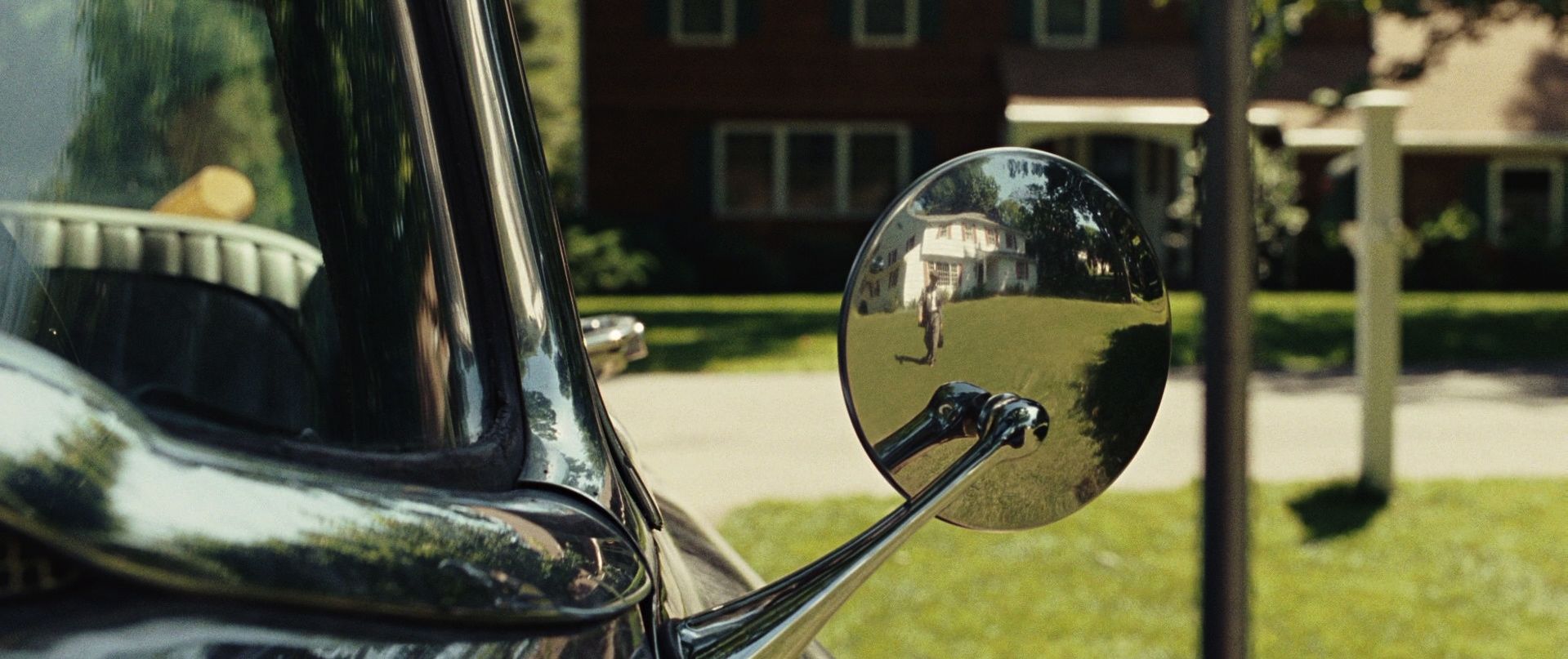

Those of us who lived in the suburbs in the first two decades of their existence know well the sense of dread evoked by the neat rows of freshly painted houses with their freshly mowed lawns — a sense of what can go wrong in such places, so difficult to escape, cut off as they are from the life of a real city or town, from corner bars or soda fountains or barber shops or churches within walking or biking distance.

Deakins really captures the sunlit hell of vintage suburbia, and makes the angst-driven narrative of Revolutionary Road seem inevitable.

Click on the images to enlarge.