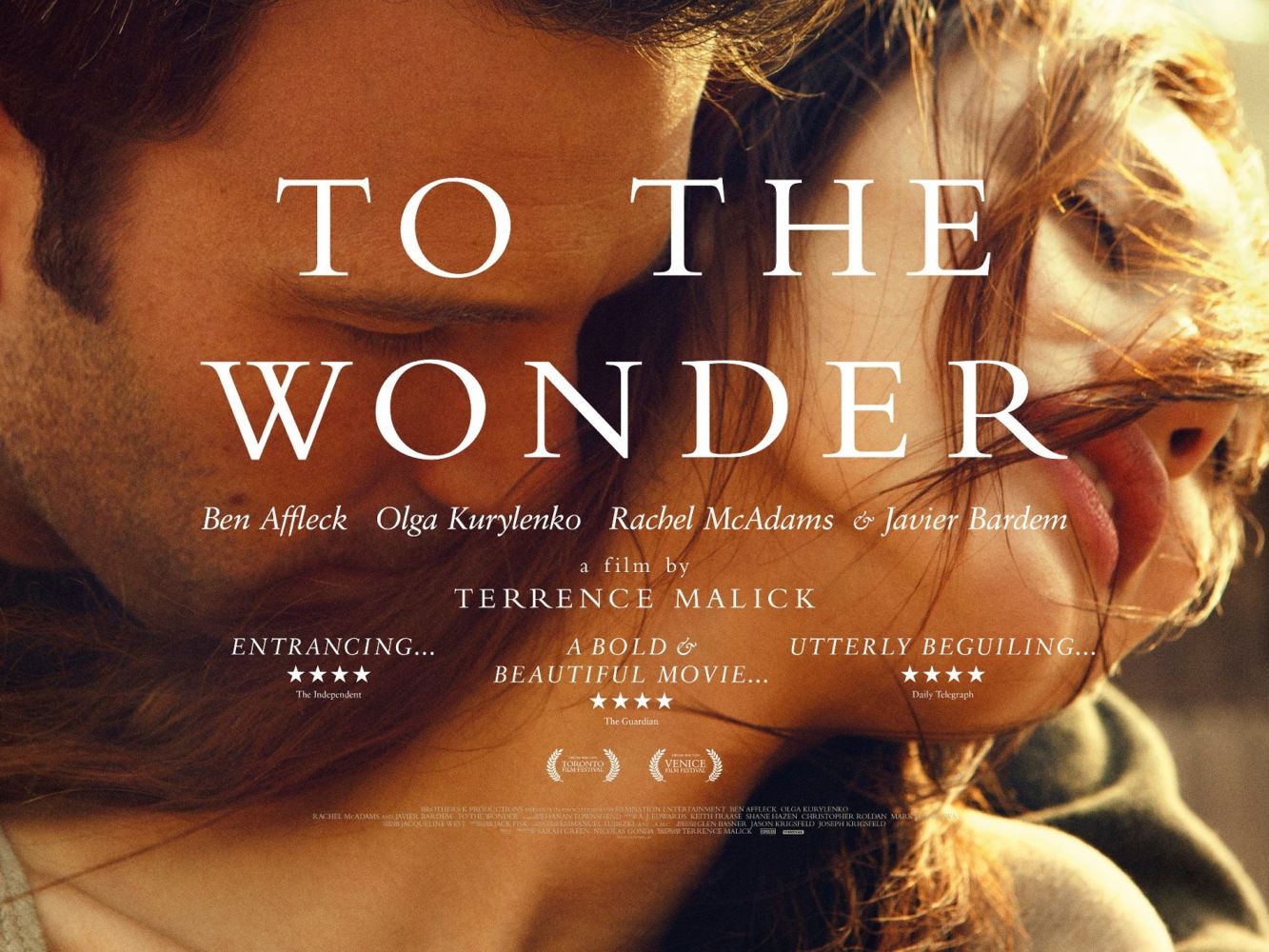

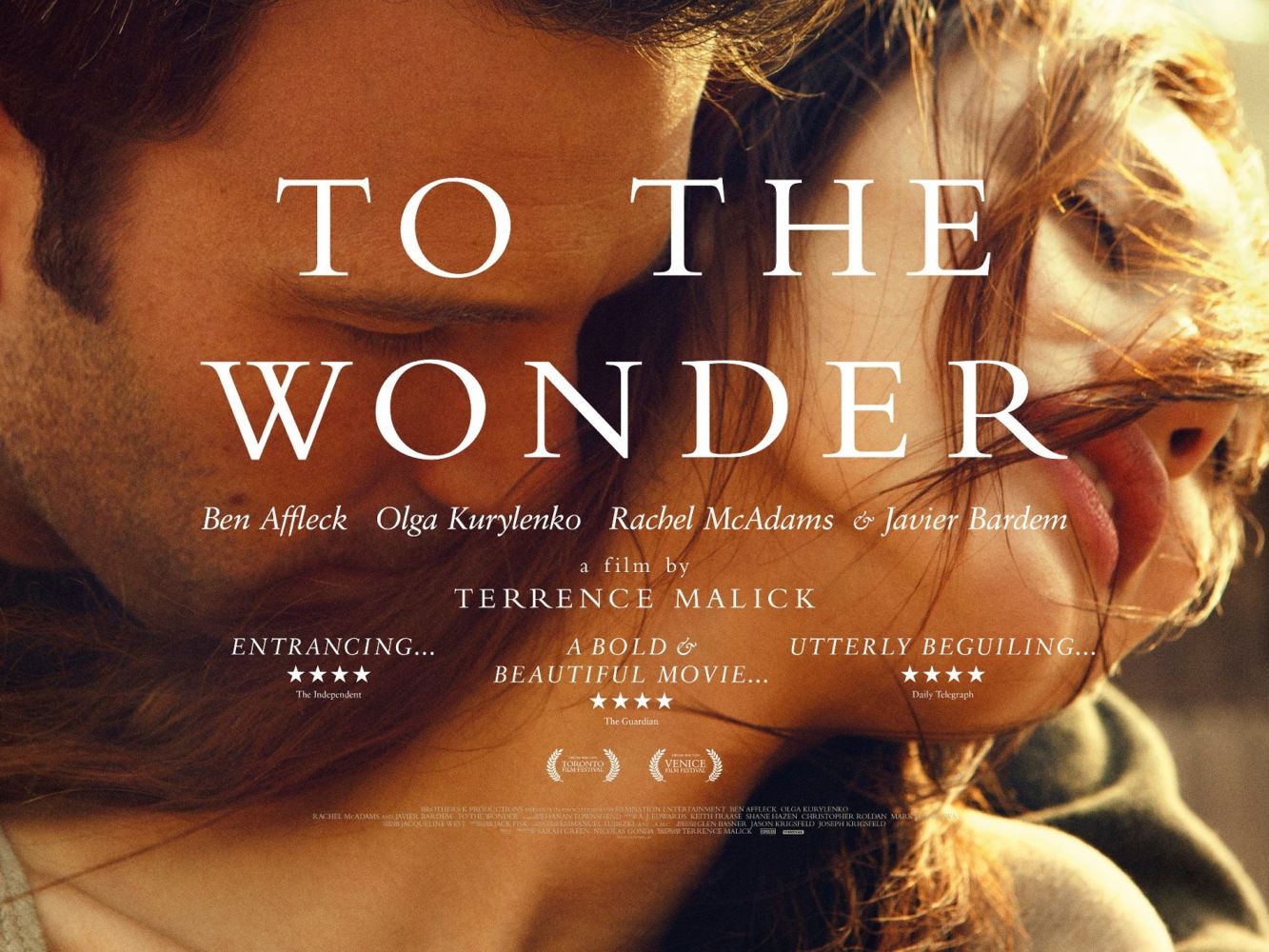

This film is a standard romantic-domestic melodrama, with one curious quirk — there is almost no expository dialogue. You have little idea what the precise issues are that push the characters together or drive them apart . . . yet since such issues tend to be generic, tiresomely familiar in real life — “She completes me” . . . “He loves me for who I am” . . . “He doesn’t listen to me” . . . “I’m losing my self” — one really doesn’t need to have them spelled out in order to appreciate the emotional ecstasies or miseries they reflect.

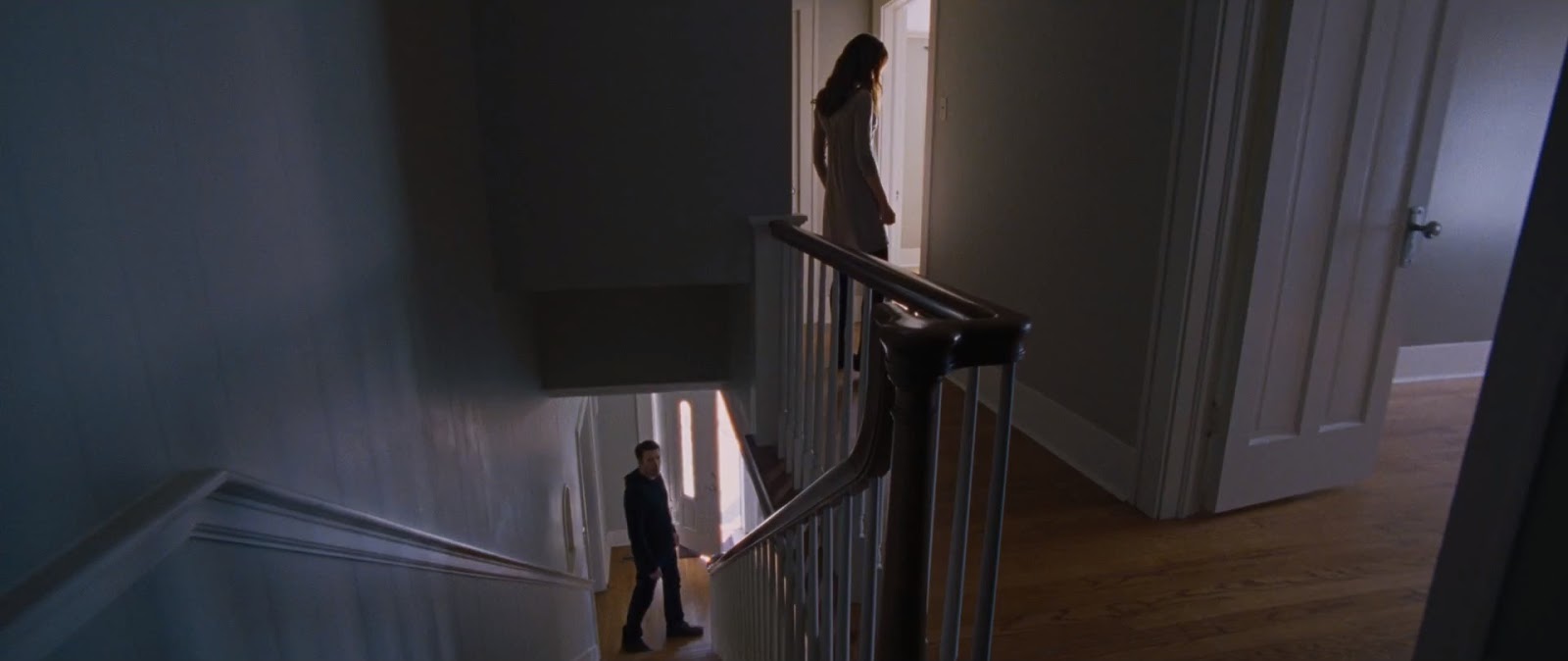

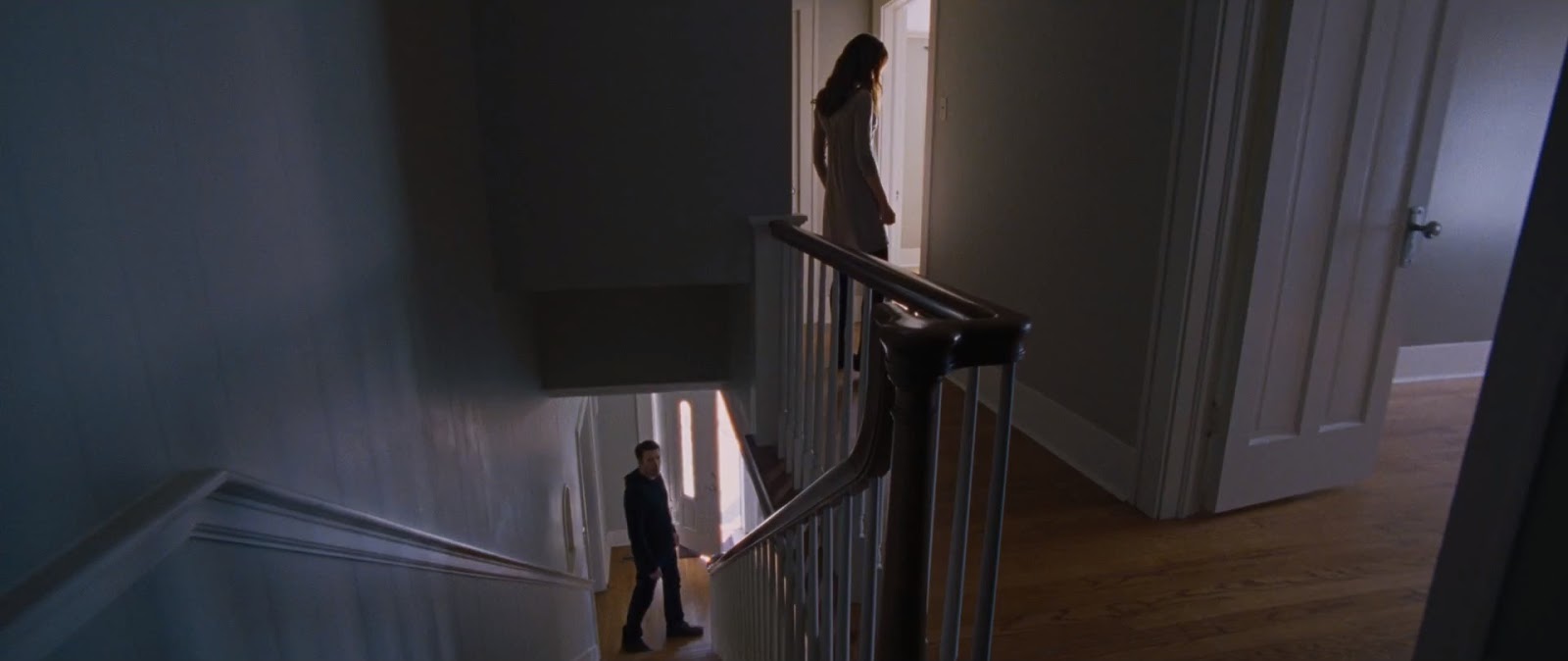

The result is a radical experiment in cinema, which tries to analyze romantic love through the spaces people traverse together, through the spaces between them, through the landscapes that embrace or isolate them, through the light that softens or exposes them.

One’s reaction to the experiment will depend a lot on one’s need for precise narrative information. I myself found the narrative perfectly legible and powerful. It is a profound insight to see love as a sort of cosmic reorganization of space, as a transformation of the world from a plastic environment defined by the position of one’s own body moving in it to a plastic environment defined by two autonomous but sympathetic bodies moving in it.

The elation of romance is thus seen to proceed not just from physical or emotional intimacy but from a redefinition, a re-charting of personal space — feeling one is there where the loved one is, wherever the loved one is, feeling that a fifth dimension has been added to one’s physical perception of the world.

Dance, including dance in movies, has often been able to express this insight, and much of the power of romance in the more naturalistic genres of cinema has to do with the suggestive choreography of lovers in space, but Malick is going after it here without the formal disciplines of dance or conventional exposition.

Malick is a religious, specifically Christian artist, and he understands the physical transformation of space by love as a form of grace — not as an expansion of our own love of creation but as a sign that creation loves us.

There is an isolated priest peripherally involved with the main characters who serves in the film primarily to demonstrate the spiritual claustrophobia of a life lived without participation in the somatic existence of other people.

The priest understands his isolation and the symbolism of the bread and wine (somatic intercourse) theologically, but he still inhabits a small and constricted space in the world, despite his desperate peregrinations through it. The lovers at the center of the film inhabit a universe of infinite space, even when they go their separate ways, because they have shared not just a vision of a merciful creation, but an actual, physical journey through it.

In Malick’s view, cinema can record this physical recreation of the world by passion or supernatural grace, and thus can record the practical workings of love. It’s about as extreme a claim for movies as has ever been made.

Click on the images to enlarge.