The fourth movie in the Noir Bars: New York

series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost

souls in desolate bars on dead-end streets. Now playing on a computer or portable device near you — a report from girlworld:

Noir Bar #4

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

Category Archives: Majestic Micro Movies

A NEW APPROACH TO NARRATIVE

Following up on a previous essay, “An Experiment In Narrative”, Matt Barry has written a broader survey of the state of Internet cinema, in which he argues that the term “short film”, with all its (increasingly irrelevant) cultural baggage, needs to be abandoned. Distinguishing something as a “short film” implies that regular films are “long”, but today, on the Internet, regular films are short — long films are the exception. In some ways it would make more sense to refer to those things they're showing at the multiplexes as “long films”.

The question, of course, is one of orientation in a time when the mainstream of cinema is shifting. I would guess that for most people under the age of forty, most of the films they watch in any given year, by far, are short Internet movies — feature-length films, seen in theaters or on DVD, would run a distant second. So what do we mean when we talk about “the movies” today? Where is the real center of the form?

Matt also makes a useful distinction between “narrative” and “story”. To my way of thinking, a narrative, a logical exposition of a sequence of events, is not by any means always a story. To me, a story is something that makes you lean forward and say, “Wait a minute, how did this happen — what's going to happen next?” A narrative doesn't automatically do this.

Check out the essay here:

PARADISE RECLAIMED

[Photo © 1960 William Klein]

An excerpt from a 2000 profile of Jean-Luc Godard by Richard Brody in The New Yorker:

During our interview, Godard referred

to the New Wave not only as “liberating” but also as

“conservative.” On the one hand, he and his friends saw

themselves as a resistance movement against “the occupation of the

cinema by people who had no business there.” On the other, this

movement had been born in a museum, the Cinémathèque: Godard and his

peers were steeping themselves in a cinematic tradition — that of

silent films — that had disappeared almost everywhere else.

Thus, from the beginning, Godard saw the cinema as a lost paradise that

had to be reclaimed.

If love of the cinema of the past doesn't point the way to new, revolutionary

work — as love of ancient Greek art sparked the innovations of the

Renaissance — then it's just an exercise in nostalgia.

In other words, the cinema of the past can be alive as a cultural force, as it

was for the young French cinéastes of the Fifties, just as ancient Greek

art was alive for the artists of the Renaissance.

The parade has not gone by — it may even be passing this way:

NOIR BARS #3

The third movie in the Noir Bars: New York

series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost

souls in desolate bars on dead-end streets. Now playing on a computer or portable device near you — a whole chain reaction of disaster:

Noir Bar #3

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

[Image by Alfred Stieglitz, 1903]

ANOTHER NOIR BAR

Now playing on a computer or portable device near you . . . the second movie in the Noir Bars: New York

series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost

souls in dark bars on dead-end streets. Have a look:

Noir Bar #2

YouTube

Facebook Fan Page

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

[Some explicit language in this one.]

AN EXPERIMENT IN NARRATIVE

Matt Barry — a fellow filmmaker and blogger and collaborator on the experiment in question — just posted an insightful piece about Majestic Micro Movies on his site, The Art and Culture Of Movies. The site is filled with interesting thoughts about movies from every era . . . including a two-part essay with great screen-grabs on the films of Edwin S. Porter. (You can access Part 1 here and Part 2 here — together they'll give you a nice little overview of the landscape of early film as the era of narrative began.)

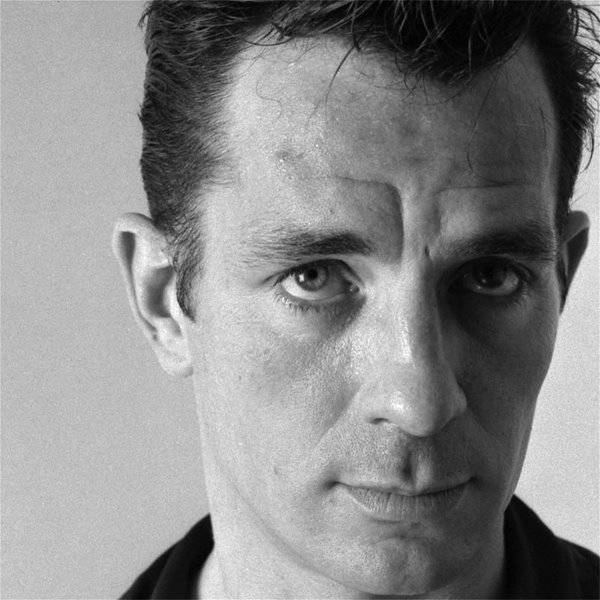

That's Matt above in the Noir Bars: New York film from Majestic Micro Movies he starred in, which will be appearing online soon. It was shot and directed by Jae Song. I know what you're thinking — it must have taken Jae forever to light that scene, with the baby spot catching Matt's eye and the ominous shadow behind him . . . but no, it was done on the fly with available light in a dark bar and a camera so small that no one knew Jae and Matt were making a movie there.

So cool.

A NOIR BAR

Today is the premiere of the first movie in the Noir Bars: New York series from Majestic Micro Movies — extremely short tales of lost souls in dark bars on dead-end streets. Have a look at it — a little Valentine from Majestic Micro Movies to you:

Noir Bar #1

YouTube

Vimeo

Facebook

Majestic Micro Movies Home Site

Watch all the films in the series as they roll out, then order a stiff drink and try to forget them.

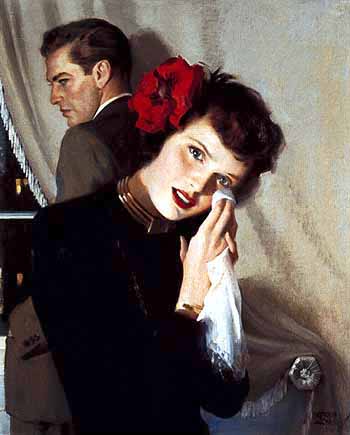

[With thanks to American Gallery for the Andrew Loomis Ladies Home Journal cover from 1949.]

SURFING THE MICRO WAVE

First there was the French New Wave — an attempt by filmmakers to retake control of cinema from the commercial or state-sponsored studios and get back to basics.

Now there's the American Micro Wave, which is basically the same thing, necessary because the eruption of cinematic invention sparked by the young directors of the New Wave has been smothered once again in corporate standardization and dehumanization.

The Micro Wave is about micro movies. This is nothing new. Micro movies dominated the early years of cinema exhibition, and micro movies dominate the Internet. The question is, can modern micro movies on the Internet get more sophisticated than cute clips from home videos, or pseudo-narratives designed to show off the filmmakers' technical skills, basically just self-generated commercials?

In short, can modern micro movies learn to tell real stories, just as directors of the nickelodeon era learned to tell real stories?

Finally, is this new Micro Wave really a wave? Too soon to tell, unless you're in the water. You can't see a wave coming until the sea-swells meet the curve of the seabed running up to the beach, lifting a crest so high that it breaks on the sand. But you can feel it if you're out swimming in it.

All I can say is, “Come on in — the water's fine!”

[“Mermaid” illustration by D. S. Walker, with thanks as so often to Golden Age Comic Book Stories, where wonders never cease.]

MAJESTIC FILMMAKING

The first of the Noir Bars: New York series from Majestic Micro Movies will be going online in a few days. Here's how they were made. Beginning with a short written monologue, Jae Song cast an actor, worked with him or her on the reading and then recorded the monologue on a small digital device.

In the course of this process, Jae and the actor in a sense created the character, or found one of the many characters lurking in, made possible by, the written text. What they did was prompted by the script but shaped by the actor's sense of it and Jae's sense of what would work as a voice-over on film.

They then repaired to a bar and began improvising behavior. Since the camera Jae was using was so small, and since he was shooting with available light and not taking live sound (apart from ambient bar sound), no one really noticed that they were making a movie. Drinking began. Jae followed his instincts visually and when he had what he needed, or when his storage card or battery in the camera ran out of space or juice, drinking continued uninterrupted. The whole shoot rarely lasted more than an hour or two.

Then Jae began the only part of the work he found tedious — editing. Fortunately his roommate Joe Griffin, a fellow filmmaker who also starred in one of the films, helped out with this.

The films only last a couple of minutes. The challenge was to create real characters and situate them in real stories. Only a brief glimpse into the character's narrative could be captured, of course, but the idea was to come up with something beyond a character study, or an anecdote — something that would set the mind to wondering . . . how did this character get into this predicament? What's going to become of this character?

When you ask questions like that, you are in the realm of a genuine story.

MAJESTIC MICRO MOVIES: TECH SPECS

About six years ago, my friend Jae Song, a filmmaker, told me, in

abject astonishment, that with the new HD cameras just coming on the

market it was possible to fit the camera and lighting package for a

feature film into the back of a station wagon.

Today, he's shooting feature-quality HD video in New York bars with

equipment he can fit into a backpack.

The center of his current package is a Canon 7D still and video camera,

fitted with a Canon 1.0 lens. That lens, no longer in production and

hard to find, and the sensitivity of the camera itself allow him to

shoot with ambient light (in bars that aren't too dark to start with)

and come up with footage that looks as good as most stuff you see in

Hollywood movies — better, as often as not, because Jae has an

exceptional

eye, artistically speaking.

The camera shoots HD video at 1080 resolution and uses the h264

compression codec — an o. k. codec, as far as Jae is concerned but not

Final Cut Pro friendly. He suggests transcoding it before editing.

The key to the look Jae gets, however, is a custom gamma contrast curve

that can be downloaded from the Internet for the camera. Out of the

box, according to Jae, the camera's images are too contrasty, looking

like bad video. The contrast curve he uses gives more info for

highlights and shadows, and thus more options in ambient lighting

situations and in post. The downside, for some, is a softer image than

the one Canon thought people would prefer, but with care it simply

gives the footage more of the feel of film. It works especially well

for Jae in

the bar settings, where the lighting can be harsh at times.

Jae shoots with the lens wide open to 1.0 at all times, at 24 fps,

sometimes varying the ISO and shutter speed slightly according to

conditions.

Jae doesn't manipulate the images in post — what he gets at the

location, trusting his own instincts about the light and the capacities

of the camera, is exactly what he wants.

A series of short films Jae shot with this camera will be appearing

soon on the Internet. You simply will not believe how good they look.

VISUAL MICRO FICTION

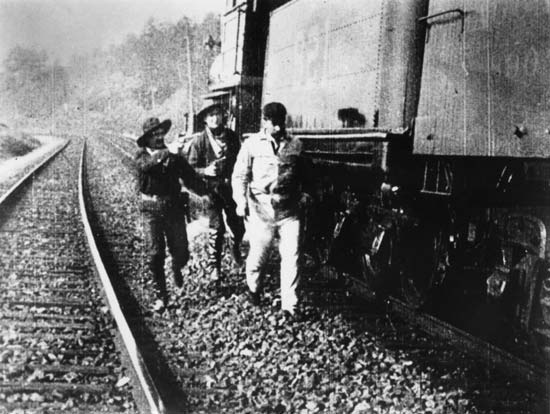

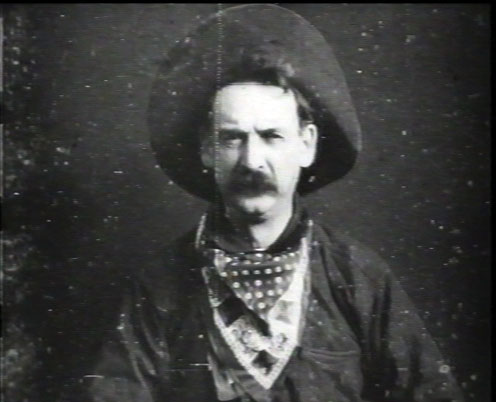

The first story films were very short — either little gags that could last less than a minute or narratives lasting about ten minutes. There's a reason for that. Because movies were a new form, novelties, they fell into story frames that audiences were already familiar with — newspaper cartoons and comic strips, which could be read in less than a minute, and vaudeville skits, which lasted about ten minutes. These familiar forms helped audiences fit story films into their habitual patterns of consuming entertainment.

In this era, movies and comic strips fed off each other, expanded each other's boundaries.

The first truly sensational American story film, The Great Train Robbery (see the frame grab above), appeared in 1903. There had been story films before this, or anecdotal films with narrative qualities, but The Great Train Robbery was so popular that it almost singlehandedly created the new market for story films. In a short time they had replaced gag films and actualities as the preferred cinematic form.

D. W. Griffith made his first ten-minute short in 1908 and at once began expanding the expressive range of the short story film. In 1909, the first regular comic strip, Mutt & Jeff (above) began appearing in newspapers. There had been multi-panel strips before this, along with single-panel cartoons that told little stories, but Mutt & Jeff signaled the emerging dominance of the strip. Just as single-panel cartoon gags had provided a template for early gag films, so the longer story films helped pave the way for the popularity of the multi-panel strip.

In the YouTube era of Internet cinema, we are about where projected movies were before The Great Train Robbery. The next step will probably be very similar to the next step projected movies took — into the territory of the newspaper cartoon and comic strip and vaudeville skit, all of which can be studied profitably as exercises in micro-fiction. The idea that Internet cinema can leap from the cute pet or baby video into feature-length narratives is a fantasy. People will eventually consume feature-length narratives via the Internet, but what happens between now and then will be intensely exciting. This is when the shape of cinema to come will be determined.

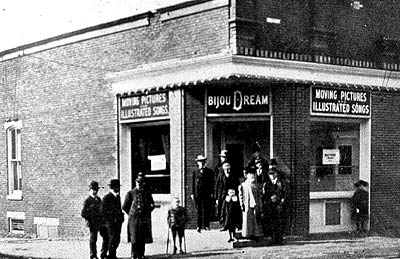

BIJOU DREAM

How do you tell stories in images on the Internet? Fast!

Is it possible to tell a real story in a micro-fictional format no

longer than a cute baby video? A filmmaking collective based in

Brooklyn thinks so — and is trying to prove it.

Cinematographer and director Jae Song has been making a series of very

(very) short films shot in bars in New York City, working with unknown

but great young (and not so young) actors. He's using a tiny Canon 7D

camera,

which shoots stills and HD video, and a rare super-fast Canon 1.0 lens.

He

uses only available light, and doesn't take live sound (except for ambient bar sound) — the actors tell their stories in voice-overs. (I've contributed scripts to the project and find myself amazed by what Jae and the actors have done with them.)

The series is called “Noir Bars”, and is part of a larger project called

Majestic Micro Movies, which will eventually include micro musicals and micro Westerns. The idea in all cases is to create micro-stories, with

fully-imagined fictional characters . .. . brief flashes of narratives

whose larger arcs viewers will have to fill in for themselves.

Not all that different from the first brief story films that caught

audiences' attention back around 1903 — a bit more oblique, perhaps, but serving the same timeless appetite for fables.

Coming soon to your own private nickelodeon — not a tiny storefront

movie theater now but a window on your personal computer or cell phone! Parking no problem!

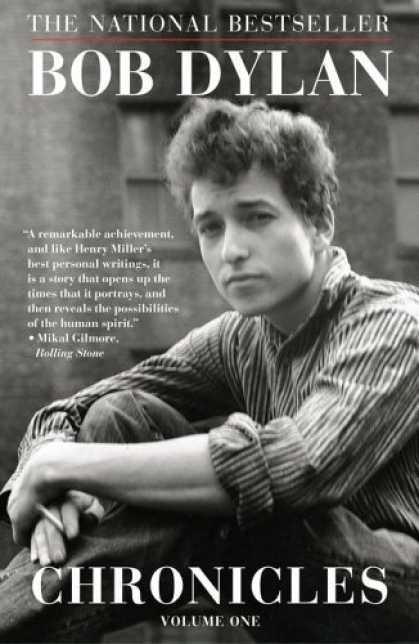

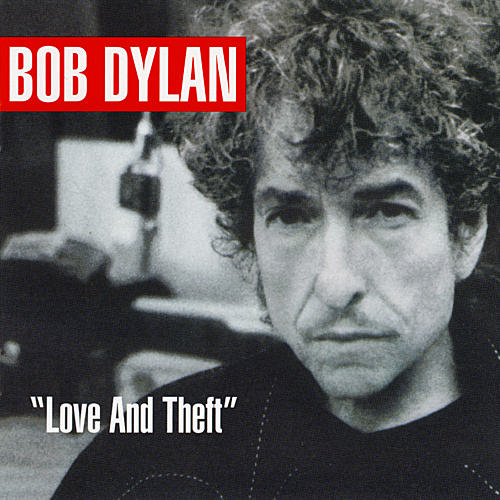

BOB DYLAN'S MICRO FICTION

In his brilliant and eccentrically revealing memoir Chronicles: Volume One, Bob Dylan talks about a crucial inspiration in his development as a songwriter — the first time he heard “Pirate Jenny”, from Brecht and Weill's The Threepenny Opera. The lyric is written in the voice of an oppressed young girl, who recounts her fantasy of a pirate ship which will appear in the harbor of her city and bombard it in her name, destroying all her enemies and rescuing her from a life of servitude.

It is thus a surreal fiction set within the slightly less surreal fiction of the opera itself, both modes operating here within a single song. Dylan says this expanded his notion of what a song could be. He was of course already familiar with the narrative conventions of folk songs, especially the murder ballads, and he would follow these conventions in many of his own works, telling self-contained fictional or historical tales, usually with a strong social message, but “Pirate Jenny” set him off on another strategy, involving fantastical tales within tales.

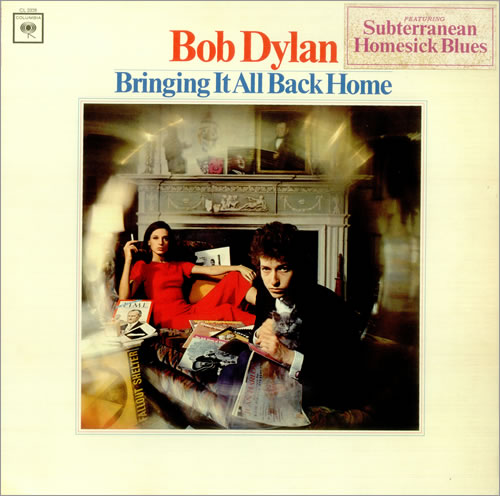

In “Bob Dylan's 115th Dream”, from Bringing It All Back Home, Dylan tells a tale in the voice of a crew member of the Mayflower, which is somehow commanded by Melville's Captain Ahab and lands in America for a series of comic anachronistic adventures. (Among the artifacts surrounding Dylan in the photograph on the cover of Bringing It All Back Home is the Lotte Lenya album on which he first heard “Pirate Jenny”.)

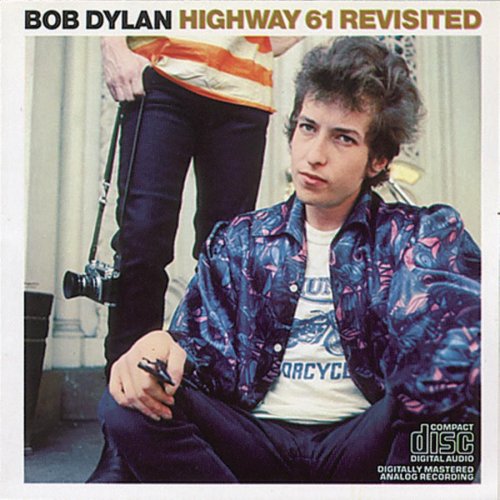

“Desolation Row”, from Highway 61 Revisited, offers a similar bit of jumbled-up, surreal narrative but has become less buffoonish, more poetic.

“Desolation Row” conjures up a vision of a very specific place inhabited by an improbable cast of characters, drawn from every aspect of culture. The real-life poets Pound and Eliot have a mythical fistfight, The Phantom Of the Opera shares the scene with Ophelia and Cassanova. It's a vision, on one level, of culture as it's actually experienced in the imagination. Lon Chaney and Charles Laughton and Victor Hugo are forever linked by The Hunchback of Notre Dame — Desolation Row is that precinct of the mind where all four of them meet up and hang out together.

On the same album, in “Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues”, Dylan presents a variation on this fractured narrative strategy, this time with a series of vignettes and anecdotes about some beat characters hanging out in Mexico. Each element of the song seems to open onto a whole narrative episode which, however, is only suggested, not recounted. It's like shards of a Kerouac novel discovered at an archaeological dig and displayed in glass cases, inviting the viewer to reconstruct the whole from them. (This is, of course, just an extension, or extreme compression, of the fragmented narrative style of Kerouac himself.)

Many Dylan songs can be seen as collages of poetic images, but most are more acutely perceived as collages of story fragments, micro fictions, which suggest great narrative vistas seen fleetingly through a narrow window whose shutters open and close quickly. His song “Floater”, from Love and Theft, suggests a whole cycle of Faulknerian novels glimpsed in this way. Ironically, many lines in “Floater” were lifted almost straight from a Japanese as-told-to autobiography called Confessions Of A Yakuza, yet Dylan has used them in the context of a series of interconnected micro fictions about a place and time and characters that seem indigenously, essentially American.

Here are eight lines from “Floater”:

My grandfather was a duck trapper

He could do it with just dragnets and ropes

My grandmother could sew new dresses out of old cloth

I don't know if they had any dreams or hopes

I had 'em once though, I suppose, to go along

With all the ring dancin' Christmas carols on all of them Christmas Eves

I left all my dreams and hopes

Buried under tobacco leaves

I doubt if any of this reflects actual memories from Dylan's own life, but the lines do seem to sum up the whole life of some particular person, in a kind of generational saga told through lightning flashes of imagery.

The precise details, the dragnets and ropes, the old cloth, the ring dancing, seduce us into emblematic episodes, in somewhat the same way that the brief flashbacks in A Christmas Carol seduce us into emblematic episodes from the happier early years of Scrooge. And Dylan doesn't just leave his hopes and dreams behind, he leaves them “buried under tobacco leaves”. Here the detail is more symbolic, more open — did the narrator lose his hopes and dreams in the drudgery of work, or just in wasted hours marked out by the smoke of cigarettes?

The details and episodes evoked in these lines propel the story Dylan is telling into our own imaginations, prompting us to fill in the rest, to travel back in time like Scrooge, to visit the narrator's lost world, to construct our own sense of it, our own dream of it. And this, of course, is what all good stories do. What's left out of them is what eventually belongs most securely to us, almost as if they were our own experiences, because we have collaborated in the making of them.

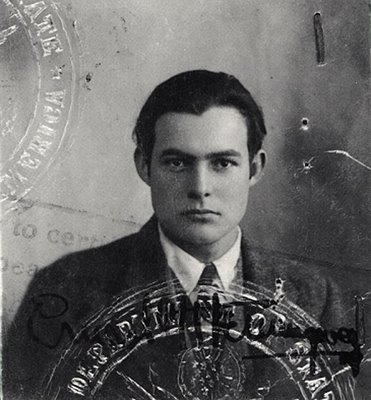

This was one of the secrets of storytelling that Hemingway knew well, and consciously, almost from the very beginning of his career as a writer. All of his best work uses this “strategic opacity”, as Stephen Greenblatt has called it, referring to Shakespeare's method of storytelling — this uncharted space that the hearer of the tale must fill in for herself.

Dylan is a great singer, a fine tunesmith and poet, but not least among his gifts is the gift of storytelling, in a fragmented, micro-fictional form of his own devising.

THE MOVIES BEGIN . . . AGAIN

When new technologies appear, the instinct is to try and figure out ways to make them the vessels for existing content. But new technologies usually need a new kind of content — or old content wholly re-imagined.

When it became possible to distribute movies on the Internet, everybody tried to figure out how aging, worn-out Hollywood content could be shifted over to the new venue and monetized. It was an effort doomed to fail. Content can never be considered apart from the means used to distribute it, and thus the ways it is consumed.

What we need to do is look at what kind of movies are working on the Internet, and proceed from there. What's working are short comedy bits, short sexy images and actualities — real-life anecdotal videos of a cute or startling nature.

It's strikingly like the content that first made movies popular, when the technology of projected film first hit the scene at the end of the 19th century. Films were novelties then — people had no way conceptually of consuming them as self-contained works. So they were shown as peep-show attractions in arcades or as interludes on vaudeville bills. What people responded to were . . . short comedy bits, short sexy images (a dancer showing a bit of leg was soft porn back then), and actualities, real-life anecdotal films of a cute or startling nature.

Plus ça change, huh?

But people soon grew tired of these snippets. They wanted longer, more coherent pieces, which meant that they wanted stories. But it wasn't possible to jump straight to any existing story form. Attention span still could not support film stories the length of plays, much less novels, or even short stories. Ten minutes was the absolute limit of attention one could count on from an early film viewer — about the length of a vaudeville skit. So a whole new form of storytelling was developed — one that incorporated short comedy bits, sexy stuff and documentary footage (of trains, for example.) But now these were integrated into a narrative.

Audiences had to learn to absorb these short narratives before they could be expanded into feature-length film narratives — into an evening's entertainment. It happened remarkably fast, primarily because the ten-minute and then the twenty-minute form was developed with such brilliant invention by storytellers like Griffith. The density of content and suggestion in Griffith's one-reelers and two-reelers, and the extraordinary beauty of his images — like the one above from The Country Doctor in 1909 — eventually made it clear (to some) that movies could hold an audience's attention for even longer than twenty minutes.

Filmmakers need to start anticipating what story forms are going to work on the Internet. There will not be a straight jump to feature-length narratives, or even half-hour narratives. Even the length of a ten-minute vaudeville skit is probably too long. What's needed are stories no longer than a cute cat video.

Can stories, real stories, be that short? Of course they can. Micro-fiction is as valid a form of fiction as any other — if it is dense with content and suggestion, if it can conjure up whole worlds beyond the frame of its images and brief running time.

Hemingway was once challenged to write a six word story. He came up with this — “For sale, baby shoes, never used.” That tells a real story, and a good one. It resonates in the mind and in the heart, like any good story. The micro-movies that will introduce real narrative content to Internet cinema will have to learn that kind of dynamic compression, and they will have to be told in images of genuine beauty, depth and inventiveness — there will be no room for the slick, throwaway non-images of the current Hollywood cinema, which have to be hurled past us at lightning speed because they would not reward close scrutiny.

This path is really the only way forward for filmmakers of the Internet era. It may seem like re-inventing the wheel, but filmmakers of the nickelodeon era were also re-inventing the wheel when they tried to figure out how to put over a grand Biblical epic in ten minutes. They seem to have had an awful lot of fun doing it, though, and in the process they created a new art form.

An essay like this can't really suggest the kinds of films I'm proposing, but my friend Jae Song is currently directing a series of movies in New York — I call them Majestic Micro Movies — which will make the whole thing clearer. You'll be able to watch them soon — here, there and everywhere.