. . . it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God Bless Us, Every One!

Category Archives: Meditations

ZOMBIE WATCH

The Church Of England voted this week not to allow women to serve as bishops. This is the church’s way of saying, “We are a rotting ambulatory zombie corpse — someone please put us out of our misery.”

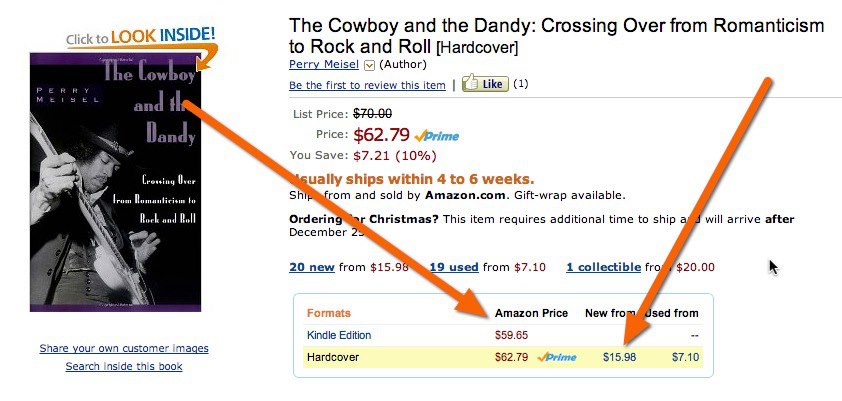

Kindle pricing by the publishing industry is the industry’s way of saying, “We are a rotting ambulatory zombie corpse — someone please put us out of our misery.” (With thanks to Ray Sawhill . . .)

I just paid a premium price of $17 to see a moderately entertaining movie on a modestly-sized IMAX screen. This is Hollywood’s way of saying, “We are a rotting ambulatory zombie corpse — someone please put us out of our misery.”

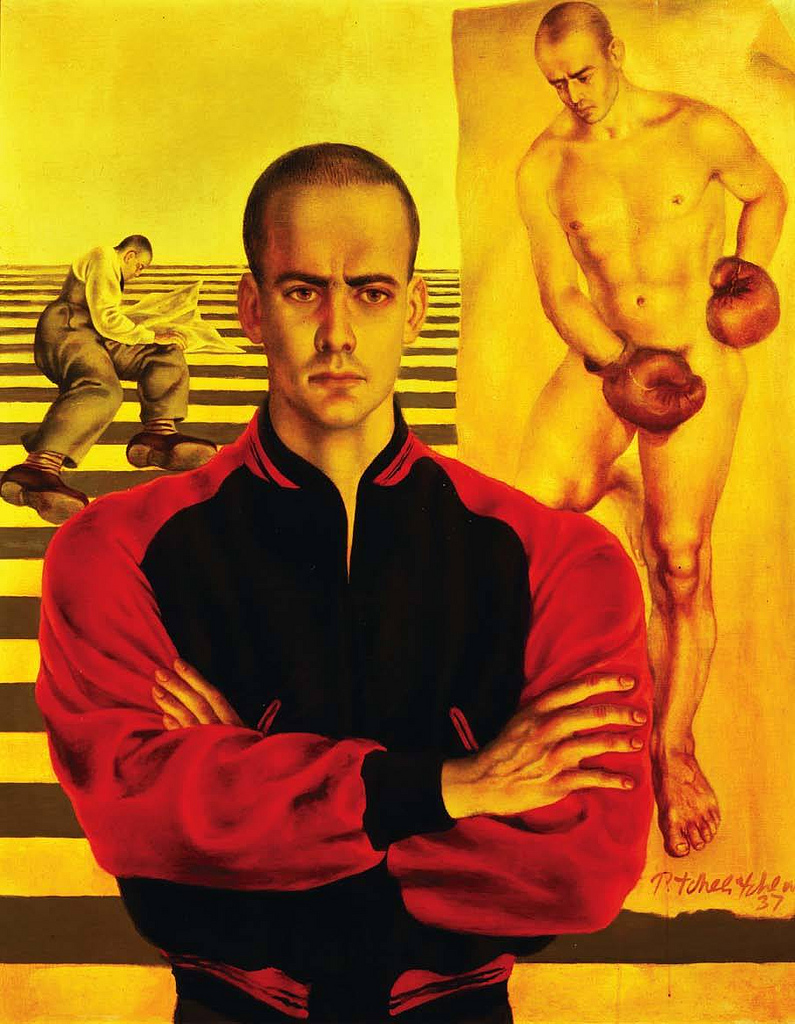

A LINCOLN KIRSTEIN QUOTE FOR TODAY

LLOYD’S MODERN LIFE: CANDLE

A Sufi parable . . .

VOYAGE TO WINDWARD

To those unacquainted with sailing, a vessel beating to windward always looks erratic.

— Joseph Furnas, biographer of Robert Louis Stevenson

Life, as you may have noticed, is a voyage to windward. Everything good in it lies at the exact point of the compass from which the wind is blowing, which means you have to tack, zigzag back and forth close-hauled into the wind, gaining only a little forward progress on each tack.

What seems to be an erratic course is in fact the fastest, the only, route to your destination.

GOD

UNKNOWN

MORE GRACE IN PRACTICE

The second part of a talk with Paul Zahl about Grace in practice — the first part of the talk can be found here.

GRACE IN PRACTICE

Paul Zahl talks about Grace in practice. A brief addendum to the talk can be found here.

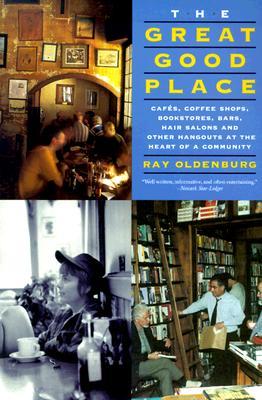

THE GREAT GOOD PLACE

It’s rare to read a work of sociology that makes you cry, but The Great

Good Place by Ray Oldenburg is such a work. Even the title touches my

heart, describing as it does a place and phenomenon which has been all

but eradicated from American life by urban planners and suburban zoning

laws . . . the local tavern, coffee house, diner, corner store, soda

fountain . . . the “third place” set in between home and work where the

sometimes overwhelming confinement of the former and the often

stressful environment of the latter can be mediated by informal

conviviality with a small voluntary community of fellow citizens.

A true third place must be convenient, not dependent on traveling a great

distance to reach, so its gatherings need not be planned — it must be

utterly inclusive, public, welcoming, and it must have regulars who

frequent it by happy choice and not out of any sense of obligation.

Whatever its physical ambiance might be, it becomes cozy and warm

through sociability, free and easy conversation, a sense of belonging

not maintained by any rules except those freely chosen by each

individual.

Oldenburg’s valuable synthesis of sociological insight into the third place, and

the dire consequences to the quality of American life brought about by

its demise, is also a quiet Jeremiad against the society, against all

of us, who have allowed this catastrophe to happen.

I think one reason people come so far in such numbers to Las Vegas is to

experience, in a brief concentrated dose, the free and easy mood of the

vanished third place — to drink and play with strangers who are not

really strangers, once greeted cheerfully and respectfully. Las Vegas

is America’s lost mythical corner tavern, with the naughty calendar on

the wall, poker in the back room, cheap food and drink at the bar. No

expectations, no networking, no snobbery — a true exercise in

democracy, inclusiveness, civility amidst diversity.

It’s a fantasy, of course, since the unique mood of Las Vegas is not

integrated into the lives of those who visit here, and so can never

take the place of a real third place. It is a great good place, though,

where you can kick back a little, forget the troubles of the workaday

world, see a few familiar faces and have a friendly word or two with

almost anyone you meet, from any walk of life and any place on the map.

Oldenburg argues persuasively that we’re not really human, fully human, if we don’t have places in our regular day-to-day lives where that is possible . . .

REVELATIONS

John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic, never consummated his marriage, which was annulled after a few years. He said his wife was “not as other women”, physically, and one biographer has speculated that Ruskin was put off by the sight of his wife’s pubic hair. Knowing the female nude only through art, he might never have seen such a thing, and might have thought it was an anomaly. His wife later remarried and had several children, so she must have been “as other women” in most respects.

The convention in most Western art, before the 20th Century, has been to present the female genitalia as a hairless mound of flesh without an orifice. (The ancient Greeks, who found the depiction of female genitalia shocking, usually presented them draped, rather than denatured.)

One major convention in modern fashion photography is to present half-clad women who are almost revealing, threatening to reveal, but not quite revealing their genitalia, or nipples.

The photograph at the head of this post is from the notorious ad campaign for American Apparel, which made a splash by violating this convention. It shows pubic hair, and other American Apparel ads have shown nipples.

I myself find this explicitness refreshing. There’s tease involved — the ads don’t show everything — but they don’t fetishize the naughty bits. Indeed, they celebrate them. They also show women as whole beings, rather than as custodians of desirable but forbidden body parts.

Most fashion photography uses sex to sell clothes. To me, the American Apparel ads use clothes to sell sex, which is often the real point of clothes, and seems a far healthier approach.

Rescuing the female body from commercialization and commodification is one of the great tasks that lie before our civilization. The American Apparel ads can’t be said to contribute much to this task, but perhaps it can be said that they’re a modest step in the right direction.

DON'T REJOICE

It's never a good idea to rejoice over the death of another human

being, even the wickedest of human beings. Wicked people want to infect

us with their inhumanity and blood lust, and if we succumb we give them

a kind of triumph. I cried when I heard that Bin Laden was dead — it

took me right back to 9/11, when I watched the Twin Towers come down

from my terrace in New York — but his death doesn't bring closure or

reparation, just a kind of crude emotional release.

The world is a better place without Bin Laden, and he summoned his own

death. He had it coming — but we've all got it coming. Now is a time

to rejoice over the courage of the special forces who risked their

lives to put an end to Bin Laden's murderous career — but it's also a

time to pray for Bin Laden's immortal soul, and to meditate on the

mystery of evil, which his death has not put an end to. It's a time to

resolve to be something different than he was.

Weep for the Bin Ladens of this world, in a way he could not weep for

those he killed.

SOHO

Remember the mornings I kissed you goodnight . . .

My friend J. B. White composed this song for a script I wrote in the early 1980s, about Soho, when that part of Manhattan was just coming into its own as a Bohemian enclave, and where I had so many magical adventures. Thirty years later, none of that Soho remains — it's a Yuppie shopping mall today — though the ghosts, the faces in the windows, are still there, I suppose, my own among them.

The places you

love that you can never return to are also places you can never

leave. They become part of your own small portion of eternity.

[Song © J. B. White]

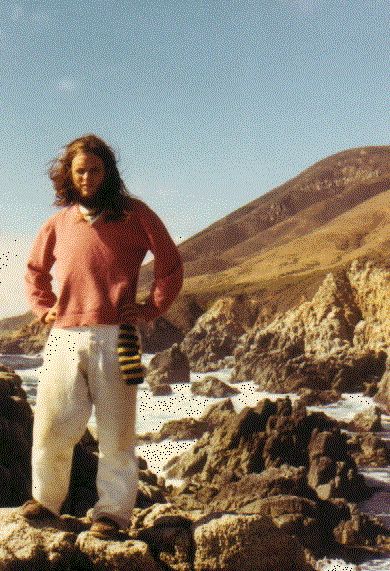

RAMBLING BOY

Sometimes I think about my rambling days — the late 60s and early

70s. Then, when it was a “damp, drizzly November in my soul”, I

wouldn’t, like Ishmael, sign on for a three-year whaling voyage — I’d

get a lift to the nearest Interstate, stick out my thumb, and . . . go.

I might have a vague destination in mind, or I might not. I wouldn’t

have much money on me — that’s for sure. Ten or fifteen dollars stuck

in the toe of my shoe. I just threw myself on the mercy of the world,

and chance. The world and chance never let me down.

It was madness, of course, in practical terms. God knows what might

have befallen me on such journeys. But people were infallibly kind and

generous, and interesting. The world seemed a sweeter and safer place

than it has ever seemed since — when I had more to lose.

When you’re homeless in this world, then you’re home. When you’re on

the road, you’re at journey’s end. When you’re lost, you’re found.

How many of us, in our rambling days, have known this . . . and

forgotten it?

SEAFRET

New tests seem to confirm Darwin’s theory that all life on earth shares a

single ancestor. But what would this microorganism have looked like?

One scientist says, ” . . . to us, it would most likely look like some sort of froth, perhaps

living at the edge of the ocean, or deep in the ocean on a geothermal vent. At the molecular level, I’m sure it would have looked as complex and beautiful as modern life.”

So we were all born, like Aphrodite, from the foam of the sea. Above is François Boucher’s visualization of the event.

Seafret, one of my favorite words, is sea foam blown by the wind.