As opposed to murder mysteries (for example), which are basically

intellectual puzzles organized around a frisson or two, great suspense

thrillers — which include many different kinds of movies, from

Hitchcock to classic film noir — are rarely about their nominal subjects. Their plots are

constructions designed to investigate and expose various modes of

existential dread which would be too uncomfortable to face directly but

which are thrilling to experience when disguised as mere

amusement. The process is very similar to what happens in dreams,

in which we find visual and plastic equivalents to inner tensions which

the conscious mind prefers to avoid confronting head-on.

There’s a smooth continuum between the suspense thriller and the horror

film, the latter category being reached when the subject of death,

bodily decay and destruction is foregrounded and taken right up to the

edge of what the mind is willing to process within a work of

entertainment. (Convention and the age of audience members play

a large part in determining where that edge begins.)

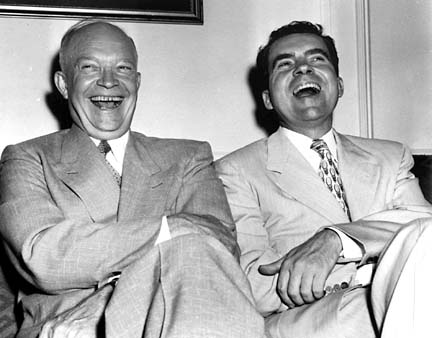

The film noir tradition, which began during and flourished just after WWII, expanded the limits of dread which American movie audiences would accept — and obviously the

horrors of the global conflict played a determining role in this development. Film noir

reflected a new cynicism about politics, since politicians had failed

to prevent the war, about civilization, which had been exposed as a

veneer beneath which savagery lurked, and about human nature, because

ordinary people did unspeakable things to each other in the course of

the war.

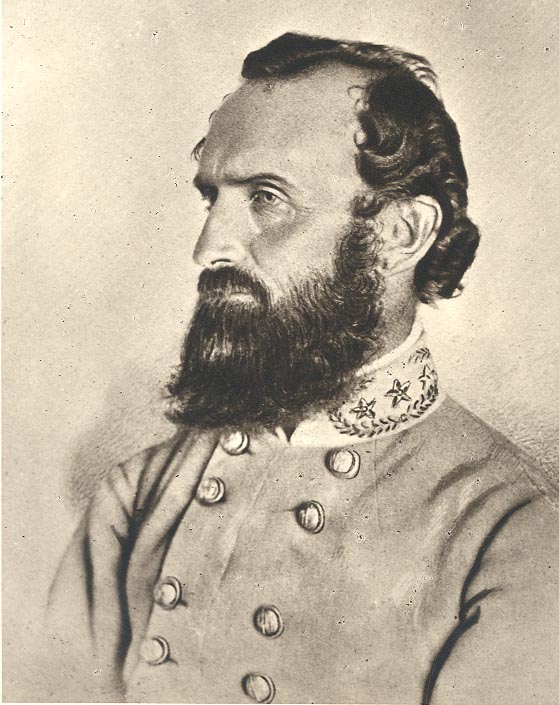

But most of all, film noir, at its heart, reflected a new insecurity about manhood.

Charles Lindbergh, before the war, wrote of his fear that a truly

global conflict would sap the virility of the civilized world and

create a vacuum in which demons would breed. He wasn’t just

talking about the young men who would be killed but the young men

whose experience of war would exhaust their spirits — leave them unfit

for the business of domestic life, the hard work of peacetime

civilization.

I think this was a profound insight, and helps explain the crisis of

manhood which afflicted 50s America and which came to fruition in the

epidemic of divorce in the 60s, along with a general retreat from male

responsibility to the institutions of marriage and the family.

The greatest generation had given all it had — its reserves of service

and sacrifice were used up.

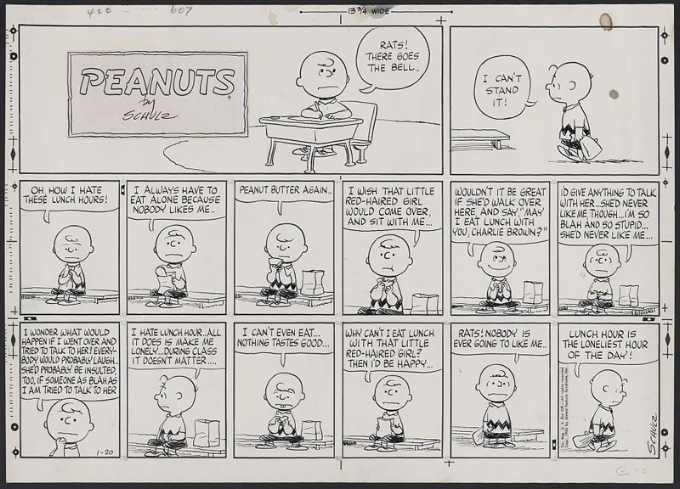

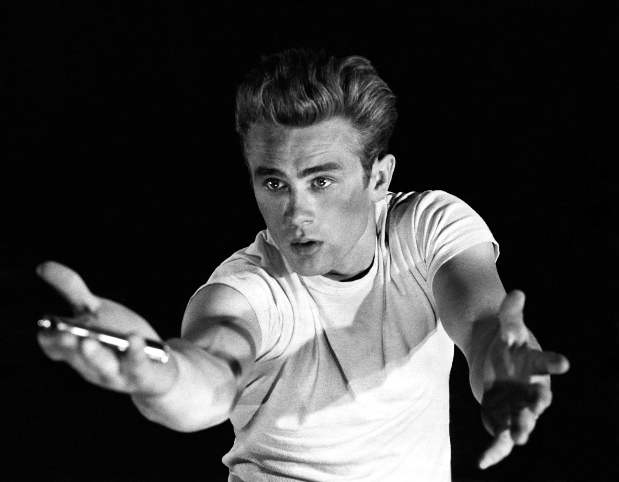

This also helps explain the disaffection of youth in the 50s and

60s, the nihilism of the Beats, the rebellion of rock and roll, the search

for newer and more authentic male role models like James Dean and Elvis

Presley — all of which culminated in a radical rejection of older male

paradigms in the 60s, in the de-sexing of the male which began with the

adolescent image of the early Beatles and ended with the long-haired

male flower child.

There was much that was positive in this cultural shift, but its root

causes and possible consequences remained largely unexamined, along

with its dark side — which was an increasing fear and hatred of women,

who could not help but represent an accusation aimed at male

uncertainty and insecurity.

It’s curious, I think, in an age which celebrates feminism and the new

sensitivity of males, that our popular culture degrades and commodifies

women to a far greater degree than earlier, frankly patriarchal

societies. Camille Paglia provided the key to this paradox when

she observed that the status of women today is determined not by a

patriarchy which has gown too powerful but by a patriarchy which has

collapsed, grown unsure of itself.

Film noir is the place to begin a study of this whole, strange phenomenon. Look at a film like Out Of the Past, one of the classics of the tradition. On one level it’s a crime

thriller, an exposé of social corruption, an exercise in cynicism about

everything. But this level is superficial. At the heart

of its tension is a vision of things gone horribly wrong between the

sexes — the dream of a lost romantic paradise, the fear that real

partnership and co-operation were no longer options, the nightmare of a

fraudulent and impossible romantic redemption.

At the center of most great filmsin the noir tradition is the femme fatale

— a tough, independent, alluring figure who’s dangerous precisely

because she exploits the impotence of her male counterpoint. The

collapsed male projects, as he always must, his own inner chaos onto

the female who exposes his weakness, his existential nullity in a

culture that no longer knows what it means to be a man.

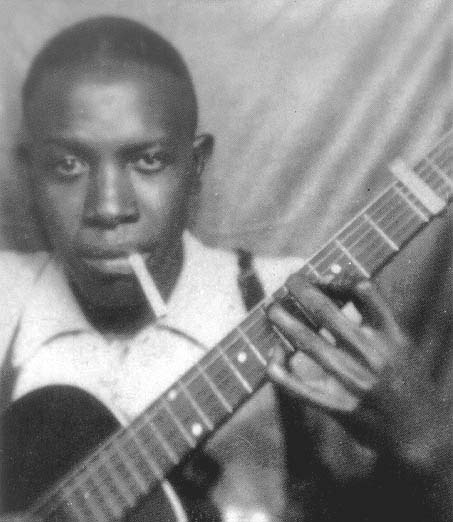

Check out the image below, where Robert Mitchum holds on to his

inadequate cigarette-phallus and Jane Greer seems to ask, “Is that it

— is that all you’ve got?”:

Cigarettes are almost always more than cigarettes in film noir.

The tough guys always reach for them when they’re trying to be hard and

cool — and when a woman smokes a cigarette, she’s usually getting

ready to un-man somebody.

The femme fatale of the film noir tradition is the mother of our modern world. It has no father.