Click on the image to enlarge.

Category Archives: Movies

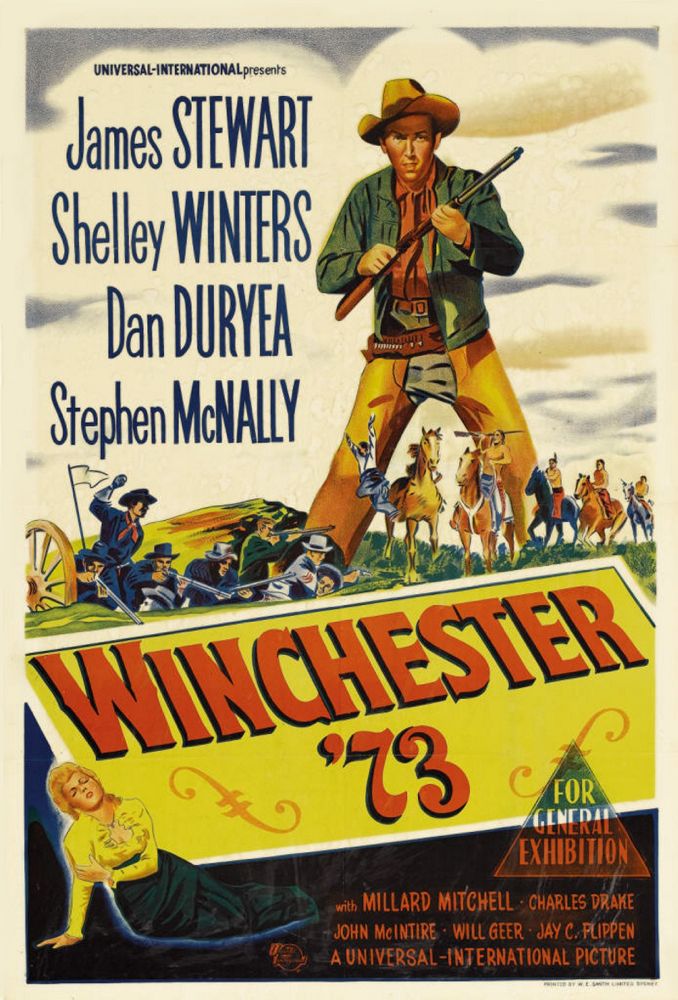

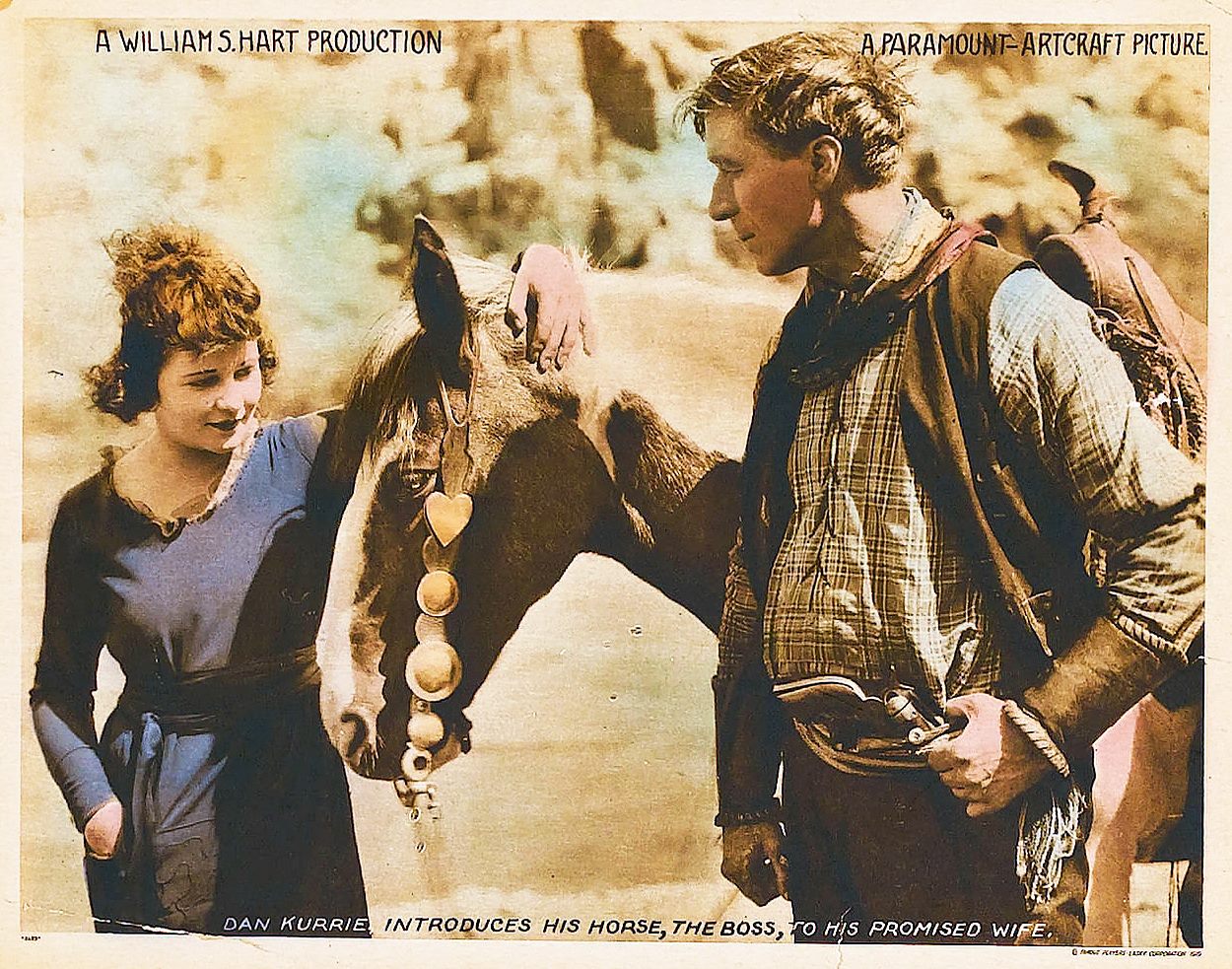

A WESTERN MOVIE LOBBY CARD FOR TODAY

THE SEA, THE SEA

BE STILL, MY HEART

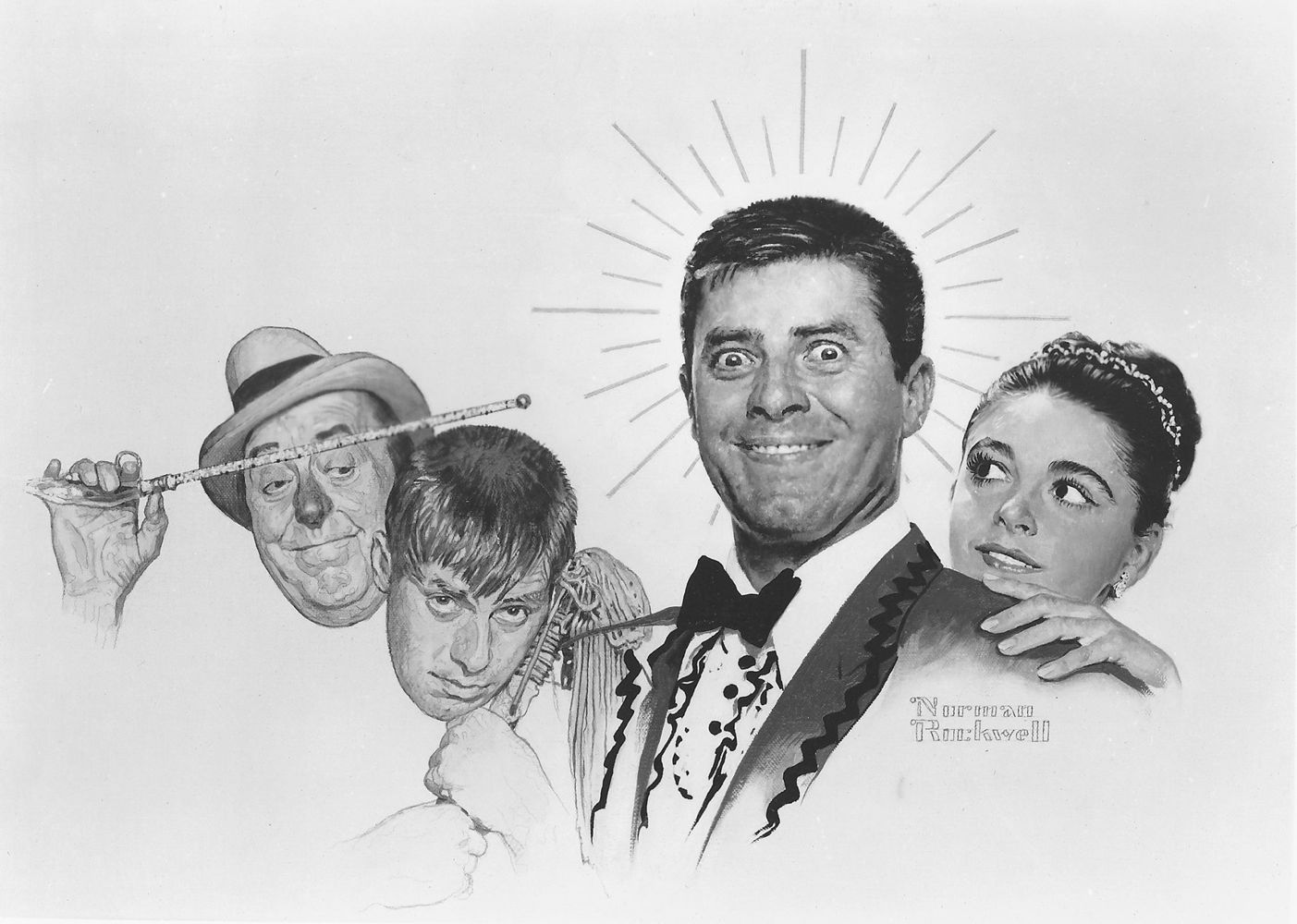

A NORMAN ROCKWELL FOR TODAY

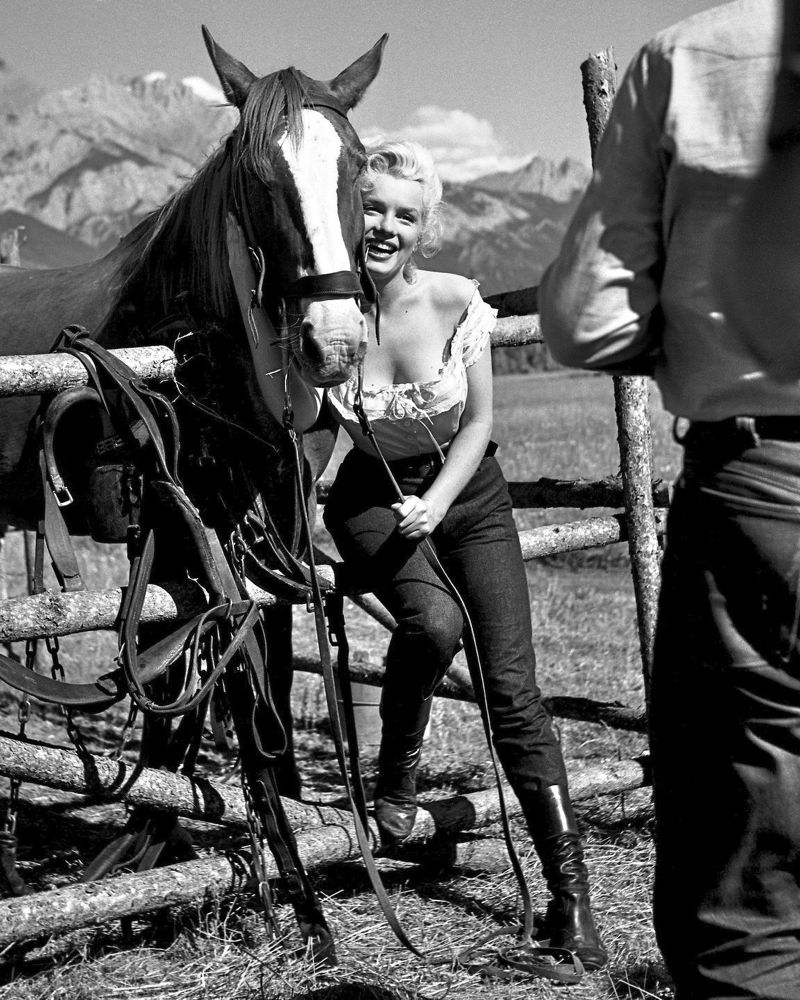

LIFE ON THE FRONTIER

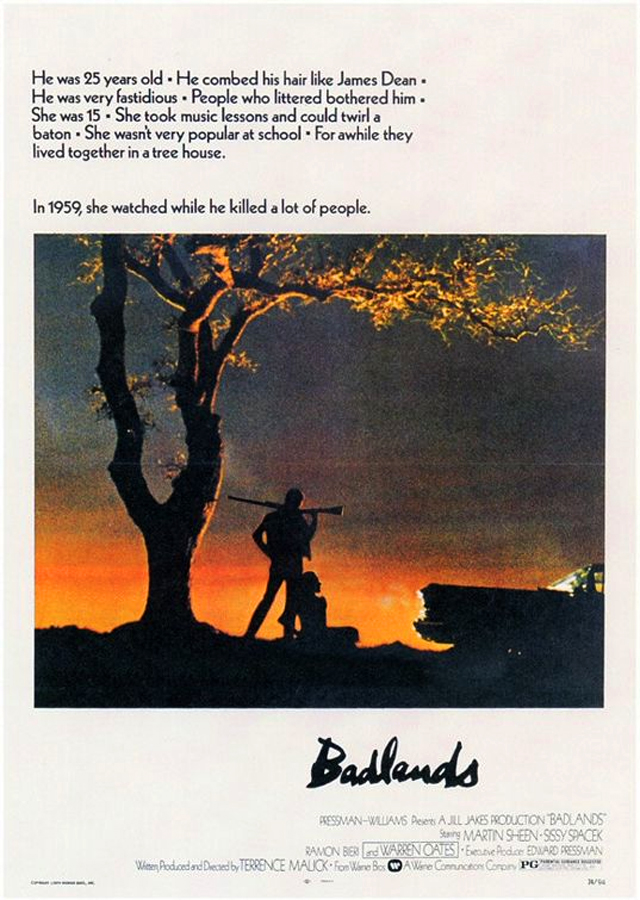

BADLANDS

When Terrence Malick’s first film Badlands came out in 1974, Pauline Kael wrote a withering critique of it, finding it to be so self-consciously arty and metaphorical, so “preconceived”, as she put it, “that there’s nothing left to respond to”. It’s a fair comment, as far as it goes, but it doesn’t really go far enough.

Malick was a protegé of Arthur Penn, and Badlands is in some ways a gloss on Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, a film Kael loved and helped to find an audience. Jay Cocks summed up the difference between the two films well. Badlands, he said, “might better be regarded less as a companion piece to Bonnie and Clyde than as an elaboration and reply. It is not loose and high-spirited. All its comedy has a frosty irony, and its violence, instead of being brutally balletic, is executed with a dry, remorseless drive.”

In other words, Badlands is a story about serial killers without the fun and visceral energy of a superior Hollywood entertainment, elements Kael valued highly, and rightly, in cinema. But a film doesn’t automatically descend into what Kael called “draggy art” just because it’s meditative and emotionally cool.

Kael said she found the “cold detachment” of Badlands offensive, but cold detachment is not the only element of the film. Indeed, Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek are such appealing screen presences, and their dialogue is so funny, that the film starts out warm and engaging. It’s only as the narrative proceeds that Malick asks us to take a step back from them, to see them as stupid and evil — to see the charm of Sheen’s Kit as repellent.

Malick wanted to play with our expectations about films of youthful rebellion, to make us slowly but surely self-conscious, even a bit ashamed, of those expectations. It’s a somewhat cerebral approach to filmmaking, perhaps, but not necessarily pretentious. Hitchcock made grand popular entertainments out of the same ambition to undermine our identification with his protagonists, keep the ground of expectation and sympathy shifting beneath our feet.

I would also argue that the film is not quite the metaphor for modern American society that Kael and others have seen it as. Kael said, “The movie can be summed up: mass-culture banality is killing our souls and making everybody affectless.” It can be read that way, I guess, but it seems to me that Malick wasn’t trying to be so dogmatic, so obvious.

Although Sheen has the active and showy part, the film is really about Spacek’s Holly. She’s the narrator of the film, and there are suggestions that she may not be a reliable narrator. Towards the end of the film she recounts an event she wasn’t present at, tells us what she thinks might have happened, and Malick shows it happening that way on screen.

It makes us wonder, in retrospect, how much of the story Holly’s been telling us is really true and how much reflects her adolescent fantasies of how it might have been or should have been. It’s yet another way of Malick distancing us from the story, but it also invites us to move closer to Holly, to try and get inside her head, and this is really quite far from the “cold detachment” that Kael accuses Malick of.

And though Holly reads celebrity gossip magazines, she’s also fascinated by antique stereographic pictures she’s brought from her home. She reads from Kon-Tiki, a popular book, but one that was ten years old at the time the movie is set and not an artifact of teen culture. Her head is filled with fairy tales and dreams of adventure as much as it is with images derived from romance comic books.

It’s Kit who sees himself as James Dean and spouts platitudes that seem to be lifted from The Reader’s Digest. He represents the banality of mass culture, but Holly wants to see him as something finer and more romantic. You begin to doubt, when you think about it, if Kit and Holly’s dreamlike idyll in the forest ever happened at all — to suspect it might just be something Holly made up out of images from Swiss Family Robinson.

Kael was right to note that there’s something overly calculated about the film, but wrong to see that calculation as simpleminded. I think Malick had subtler and deeper ambitions for the film than creating metaphors about modern society. He had begun, haltingly and vaguely perhaps, his investigation of the imagination’s role, love’s role, the beauty of nature’s role, in reconciling us to life — even a life as bleak and hopeless as Holly’s.

HOW WOMEN AGE

Our culture doesn’t set much value on the beauty of older women. As a result of this many women as they age resist the work of time, dye their hair, take knives to their faces, in a ghastly, hopeless effort to keep looking young.

It’s madness, of course, because older women can be extremely beautiful, and not just beautiful the way an old faded photograph is beautiful, but beautiful the way an old wine can be beautiful — intoxicating, and arousing.

I once ran into Tanaquil Le Clercq at a party in New York in the 1980s. She had been a principal dancer at The New York City Ballet in the 1940s and 1950s, wife and muse of its founder George Balanchine. She was still stunningly beautiful. My friend Kevin Jarre was with me at the party and he leaned over to me and said, “Look at that woman, Lloyd. She makes me . . . tense.”

He meant that she aroused him as an erotic being. She was at the time about 60 and confined to a wheelchair.

Elizabeth Warren is ancient by modern standards — in other words, my age, 64 — but her volatile intellect and energetic idealism make her erotically alive, a desirable woman, while the exhausted cynicism of Hillary Clinton is reflected in the crumbling of her face, which is starting to look like the crumbled face of Jan Brewer, the mean-hearted governor of Arizona. These are not women you’d want to take home with you, even at 3am after a long night of drinking.

I just saw an interview with Sissy Spacek from 2012 and felt that she was far sexier at the age of 62 that she had ever been in her so-called prime.

Let’s be frank here — I’m not talking about the beauty of older women as an abstract value, I’m talking about fuckability. Our culture has a sick and perverse notion of what constitutes fuckability in a woman. Many older women, who grow bitter and cynical and desperate before their time, pass beyond fuckability. Tant pis. Others keep their fuckability alive. Our culture needs to be more alert to their erotic power.

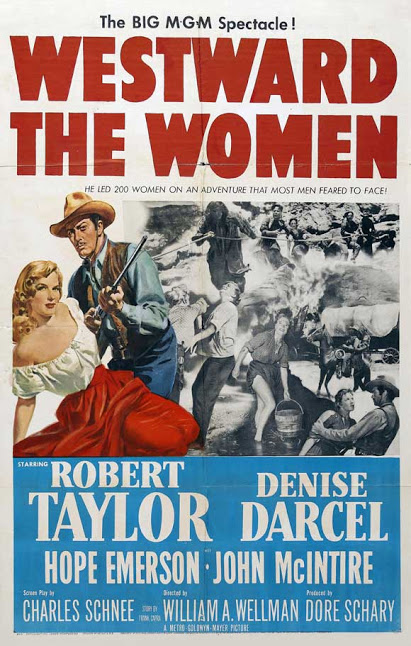

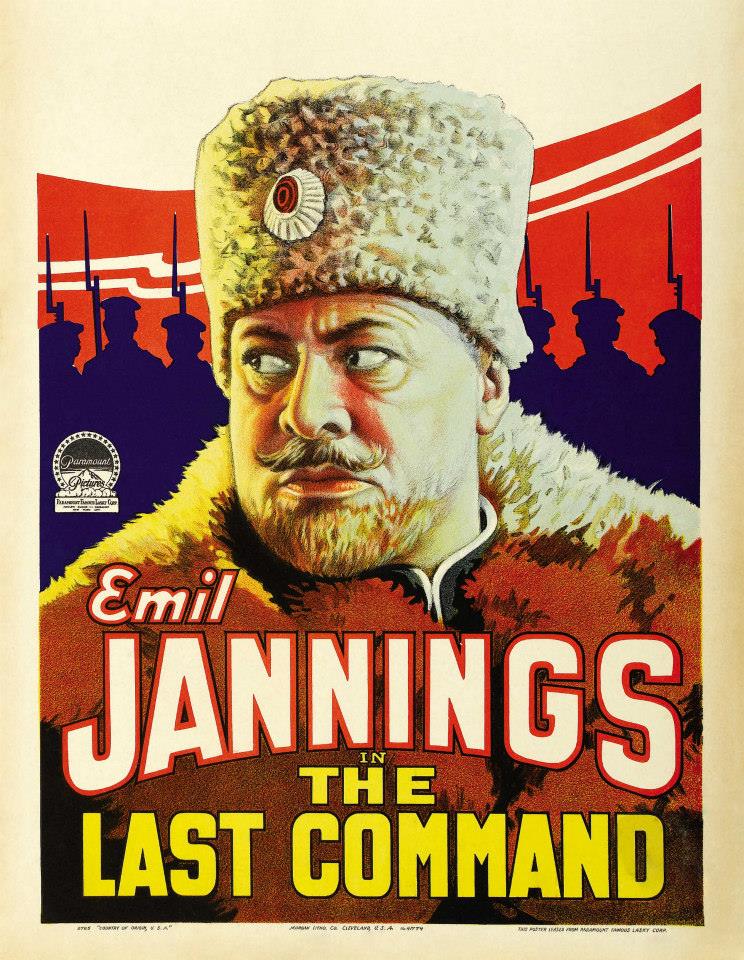

A MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

A SILENT WESTERN LOBBY CARD FOR TODAY

WESTWARD THE WOMEN

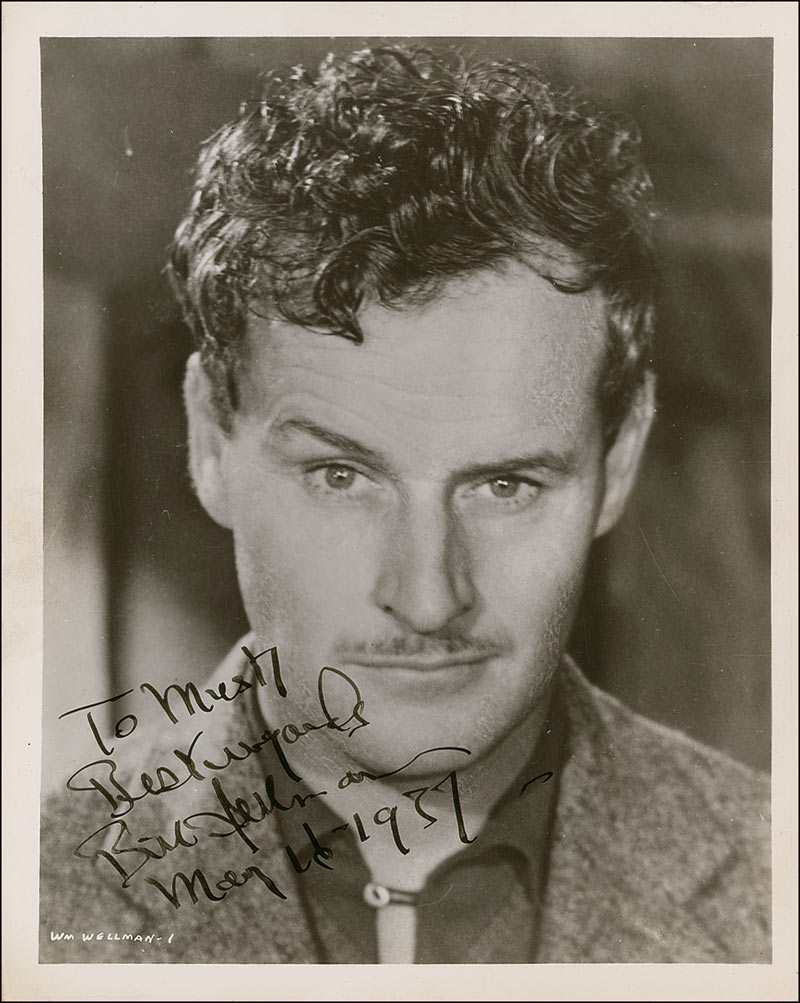

A lot of Hollywood directors who earned their spurs in the silent era and survived into the sound era had backgrounds far removed from the picture business. A number of them were mechanics, race car drivers, pilots. They were what used to be called manly men, and they brought a traditional masculine perspective to their work in action films. I’m talking about guys like William Wellman, Howard Hawks and Victor Fleming.

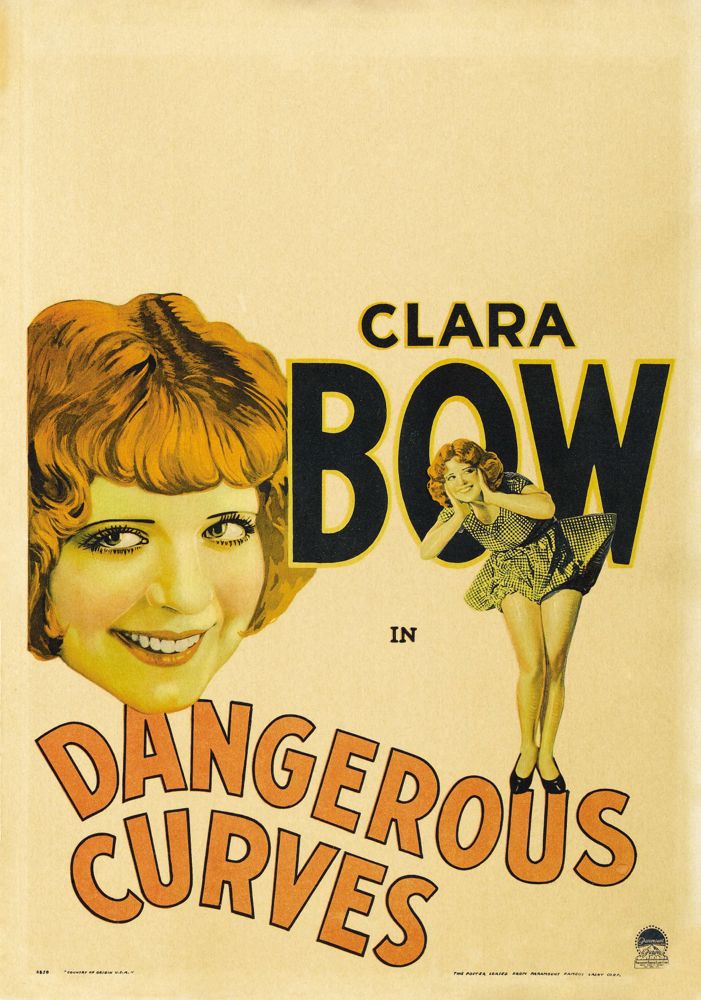

Curiously, these men were also exceptionally skilled in presenting strong women on screen — they seemed to be fascinated and not in the least bit threatened by strong women. Victor Fleming, who directed Gone With the Wind and The Wizard Of Oz, both anchored by strong female leads, was also the first director to let Clara Bow do her thing on screen in the silent film Mantrap, in which she ran sexual circles around her male leads and laughed at them while she was doing it.

Hawks unleashed Hildy Johnson and Sugarpuss O’Shea and Lorelei Lee on equally defenseless males and made us laugh at their invincible power and wit.

In 1951 William Wellman made the very odd Western Westward the Women about a wagon train of mail order brides making a 2000-mile trek from Chicago to California to hook up with prospective mates on the frontier. There are a couple of ex-hookers among them, hoping to turn over a new leaf, but they’re mostly “good women” looking for good husbands.

They’re led by the exceptionally competent but distinctly misogynistic trail guide Buck Wyatt, played by Robert Taylor. He admits up front that only two things in life scare him, and they’re both “good women”. He says he hates women’s cooking, and doesn’t expect much out of his charges except suffering and perseverance. He hires a gang of men to provide for their defense on the journey.

But then most of the men desert the train when Wyatt executes one of them for raping a woman. Wyatt wants to turn back but the women won’t turn back, even if he does. At that moment they become the heroes of the film, and Wyatt watches as they do what needs to be done to get the train through, at first amused, then a little bit awestruck.

The women don’t turn into men. Before they arrive at their destination they insist on stopping so they can make themselves presentable when they meet their future partners. Wyatt doesn’t understand this — it seems a little “girly” after all they’ve been through — but he’s past arguing with them. They’re his equals as trail bosses now.

Yet when the women show up to meet the men they’ve prettied themselves up for, their spokeswoman makes it clear that the women will do the choosing. Their passage across the continent may have been paid for by the men, but the women are in charge of the pairing up — they’ll have the last word on that.

Wellman presents all this with little comment — not making a point of female courage and competence, just showing it. Nor does he patronize the women’s desire to make themselves attractive at the end. He just respects it without judgment — not suggesting that they’ve turned back into “girly girls” but accepting that they’ve always been girly girls, as well as tough characters, as tough as any man. They can work like men, and fight like men, and die like men, but they’re . . . different.

Wellman was a tough guy — he won the Croix de Guerre with two palms flying airplanes in France in WWI. It took a tough man to make a movie like Westward the Women.

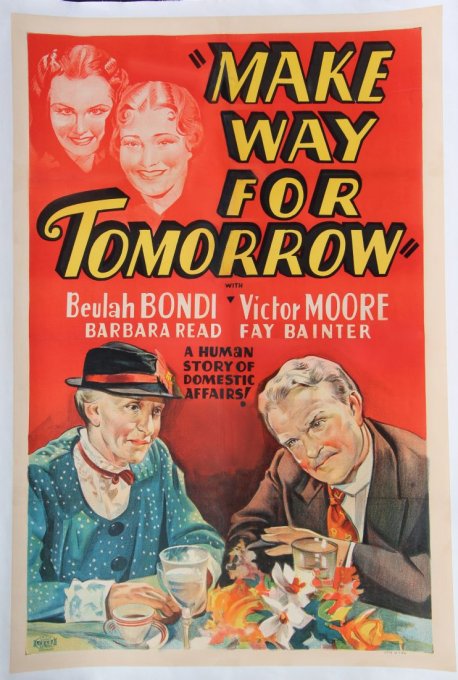

MAKE WAY FOR TOMORROW

Orson Welles said this movie made him cry like a baby. It certainly made me cry like a baby. It may be the best tearjerker of all time, or at least the best tearjerker that isn’t about young love doomed. This one is about old love doomed.

It’s one of the most disturbing movies ever made. Everybody in it is annoying to one degree or another, and yet everybody has their reasons. Every scene of family dysfunction is wrenching, and yet every situation is familiar, painfully familiar.

It’s about the way parents annoy and embarrass children, and the way children hurt and disrespect parents. It’s about problems without solutions, wounds that can’t be healed. When tiny moments of grace intrude, from the kindness of strangers, from an inarticulate expression of love perfectly understood, they pierce the heart like arrows.

I can’t recommend it even for a good cry — you’ll cry but you won’t enjoy it. It elicits tears that burn. But in its own way it’s profound, a masterpiece — the sort of work that makes you want to change your life, and hope it’s not too late.