I’ve always disliked The Wild Bunch for what I see as its moral nihilism — a violation of the Western genre which it did so much to undermine, and of the very idea of humane art. I don’t think art should make moral judgements or preach moral lessons, but I think it ought to reflect a world where moral questions are important and have consequences.

That’s a personal viewpoint, admittedly, based on my experiences in life, and on my evaluation of great works of art in general. I respect other viewpoints, even if I don’t like or admire them. The idea that human actions have no moral meaning, only a relative meaning based on individual will or style, strikes me as immature, puerile and destructive. It’s defensible as a philosophical proposition, but I reject it, and I don’t think it has ever produced any great works of art.

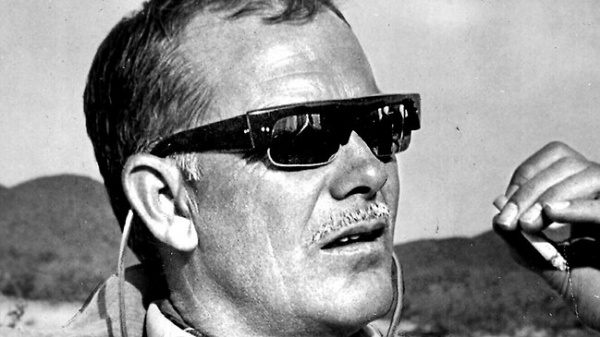

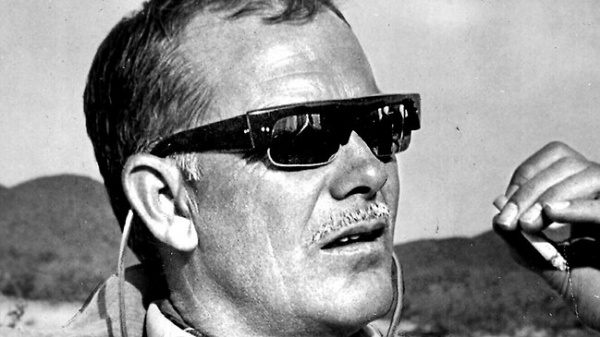

I decided recently to revisit The Wild Bunch, motivated primarily by my respect for the opinions of my friend Scott Bradley (above), who can argue eloquently against the idea that The Wild Bunch is a work of moral nihilism. I also read a few critiques of the film which take the same view.

The Western was losing its cultural prestige in 1969, when Peckinpah’s film came out. The Vietnam war was making many people doubt the ideals America prided itself on, making them wonder if those ideals had always been fraudulent. The Western, embodying a mythology which tended to affirm those ideals, was an obvious target for a revisionist view of such things.

The genre, taken as a whole, had always had room for moral complexity, for good guys who weren’t all that good and bad guys who weren’t all that bad, but it generally held that bad guys could be morally redeemed by honorable acts and that good guys who made bad moral choices would pay a price. Vietnam made some artists, and a big segment of the audience, wonder if that formula, as applied to America in Westerns, was meaningless, and always had been.

As the 60s progressed, Westerns got edgier and darker, and more ironic. Spaghetti Westerns leaned heavily on an irony verging on outright farce. They tended to keep the moral distinction between good guys and bad guys, but they presented the conflict with a wink, suggesting the whole thing might be a joke. Western fans beginning to doubt the genre could have it both ways, rooting for the good guys while not taking them too seriously.

In his 1968 film Once Upon A Time In the West, Sergio Leone cast Henry Fonda as a vicious killer, an unredeemed bad man. It had a certain shock value, but it didn’t upend the moral dynamic of a traditional Western — we weren’t asked to root for the Fonda character, though we may have wanted to, given Fonda’s status as an iconic movie hero. This created an interesting tension.

In The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah took things further. His main protagonist was William Holden, another iconic movie hero, playing Pike Bishop, the leader of a gang of outlaws. In the first scene of the film, the gang is robbing a railroad office. A couple of hapless clerks and a woman are caught inside the office. Bishop says to his men, gesturing to the clerks and the woman, “If they move, kill them.”

This is roughly equivalent to Fonda killing a child at the beginning of Once Upon A Time In the West — it has the same shock value — but the similarity ends there. In The Wild Bunch as it unfolds we are asked to root for the Holden character, to admire him, a man who would murder an unarmed woman to commit a robbery. To me, this takes us into the territory of moral nihilism.

Bishop is cool, with the bearing and the aura of an iconic Western hero. He’s brave and competent, and loyal to his fellow outlaws. His willingness to murder innocent unarmed people is treated as morally meaningless. It’s something a hero can do if he wants to or needs to and still be a hero.

In a traditional Western, even a dark modern one like Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, we would expect a vicious killer like Bishop to have a change of heart, to recognize his own moral nullity, to be given a chance to redeem himself. But neither Bishop nor Peckinpah sees any need for redemption. Bishop’s style and will and bravery are redemption enough.

There are, as I say, arguments against this view — centering on the idea that Bishop and his gang, when they flee into Mexico, are touched by the goodness of the Mexican peasants and eventually sacrifice themselves in the cause of the peasants’ revolt against their corrupt government. I myself don’t see evidence for this in the text.

They certainly sympathize with the peasants and are disgusted by the corruption and viciousness of their oppressors, but they don’t think twice when the vicious and corrupt Federal general Mapache hires them to rob a U. S. Army train of the weapons it’s carrying, back on American soil, and deliver the weapons to him. They’re completely fine with killing American soldiers to accomplish the robbery.

It’s true that they agree to given Angel, a Mexican member of the gang, a case of rifles to pass along to the insurgent peasants, but only in return for his share of Mapache’s money. The wild bunch remain true to their nature — a gang of moral monsters, who will do just about anything, even the right thing, for money.

Bishop is not shown actually murdering an unarmed women, but in the opening he leaves the clerks and the woman in the railroad office as hostages in the charge of a psychotic gang member who does kill them when they move, trying to escape. They die off-screen — perhaps because Peckinpah doesn’t want to show us the graphic consequence of Pike’s repellent indifference to innocent human life.

Angel is shown murdering an unarmed woman, a former lover he kills because she has betrayed him and taken up with Mapache. There is no sign that any of the wild bunch has any moral qualms about this atrocious act. Quite the opposite in fact. At the climax of the film the gang sacrifices itself in an effort to rescue Angel from the Federales — a hopeless gesture which they know won’t succeed. In essence, they commit “suicide by Federales”, preferring to go down fighting rather than endure the fact that their era on the frontier is coming to an end.

Their suicide walk is justly famous — it’s designed to portray the outlaws as heroic, even though there’s nothing heroic about what they’re doing. Attempting to rescue “one of their own” is just a pretext for going out in a blaze of cosmetic glory. It’s no more heroic than the 9/11 terrorists flying planes into The Twin Towers — sacrificing their lives “bravely”, perhaps, but in the service of an ignoble cause.

Peckinpah can’t even allow the bunch to commit suicide honorably — at one point in the climactic shootout Dutch saves himself temporarily by using an unarmed woman as a human shield. She takes a bullet meant for him. The perversity of this is extreme. You get a feeling Peckinpah was expressing a deep contempt for the audience, mocking it as he was mocking the Western genre itself, because he could get it to root for such vile “heroes” as these.

I’ve read a “feminist” defense of Angel’s murder of his former lover, seeing it as a blow against the corrupt government that’s oppressing his people, a political act, motivated by Angel’s own self-hatred over his impotence in the face of that oppression. This is plausible psychologically, but it avoids the moral issue of murdering unarmed people, which doesn’t seem to interest Peckinpah at all, any more than it interests Bishop.

Understanding Angel’s act, even sympathizing with it, is not an excuse for utterly ignoring the moral questions it raises — again, on a par with understanding the motivations of the 9/11 terrorists while totally ignoring the moral questions raised by their act of murdering unarmed people.

I’m not saying that Peckinpah had an obligation as an artist to condemn Angel — only that ignoring the full moral dimensions of Angel’s act, in effect trivializing them, is an exercise in nihilism. In The Wild Bunch in general we are asked to cheer for some truly despicable men, to ignore their despicable acts, to revere them for their style and courage alone. It’s a shabby, puerile view of the world, and makes for a shabby, puerile film.

Peckinpah was a more complicated artist than The Wild Bunch would indicate. He loved showing the dark side of human nature without mitigation or pious revulsion, but he rarely presented that dark side as something to be laughed about, relished, celebrated as heroic. His own dark side led him into a life of creeping, harrowing despair — he knew only too well the price of a dalliance with moral nihilism, and that knowledge informs his best work, gives it depth and complexity. It’s entirely absent from The Wild Bunch.

So in the end, after revisiting the film with as open a mind as I could summon, I find that I still dislike The Wild Bunch intensely — for much the same reasons I outlined in an earlier post here. The film traffics in images of heroism, albeit stirring images of heroism, that are cheap and hollow and repulsive.