Click on the image to enlarge.

Category Archives: Movies

BLUE JASMINE

A mean, sad, bitchy movie about a mean, sad, bitchy woman — the narrative of a life on the skids presented without grace, without mercy, without a hope of redemption.

You can indulge your schadenfreude to the fullest here, courtesy of Woody Allen in full bitch queen mode, then slink home and try to forget the whole episode.

Good luck!

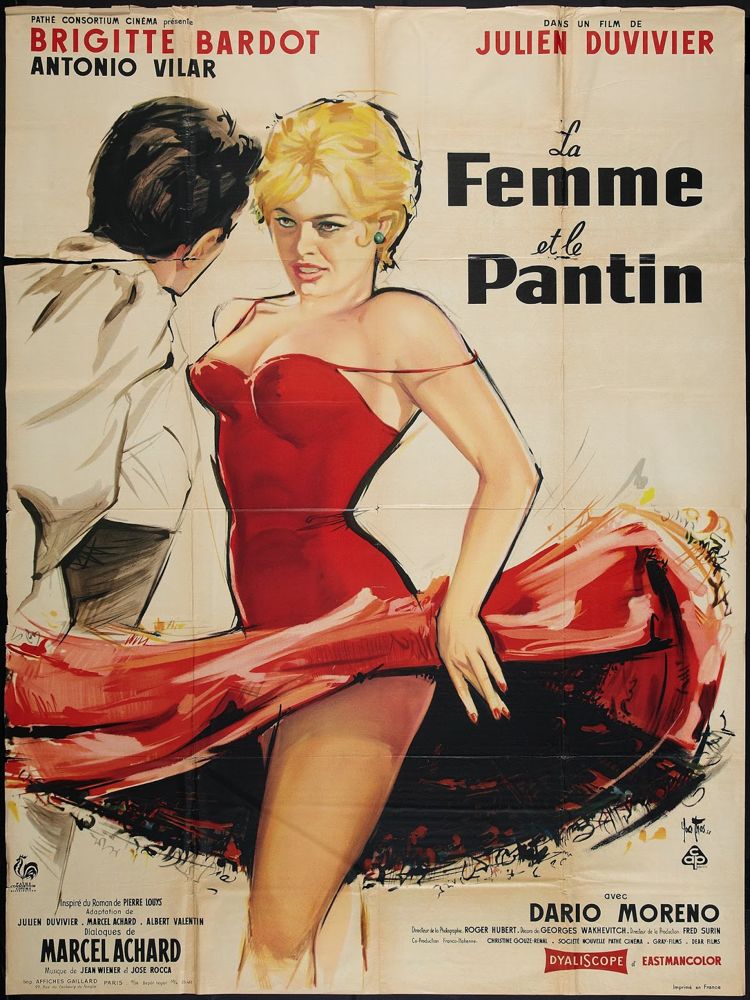

A MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

THERE’S JUST SOMETHING

HÔTEL DE CHAGRIN

Last night I dreamed I checked into an old hotel somewhere in Europe with Françoise Dorléac. It was a dark place with dark wood paneling.

In the hotel room, when Mlle. Dorléac took off her make-up her face began to glow white, uncannily, as though from within — as though she were in the process of becoming a ghost.

I woke up before the process was completed. In retrospect this dream encounter was not scary, just strange and sad.

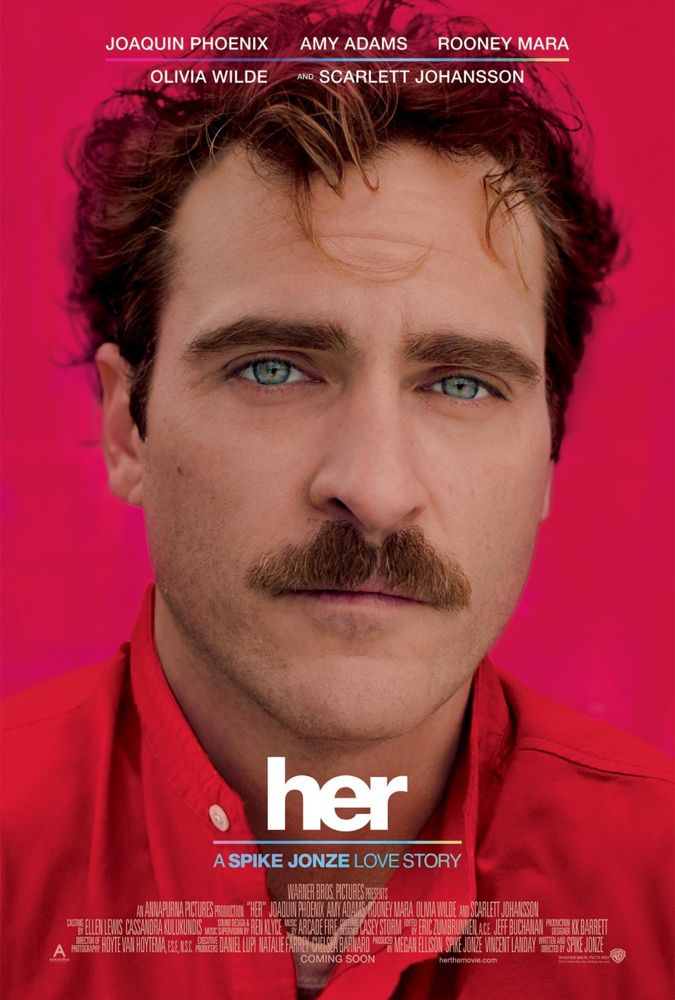

her

This film would not have made sense ten years go — now it makes too much sense for comfort. It’s nominally about a guy named Theodore who falls in love with the sultry voice, witty style and consoling charm of his smartphone’s operating system. The tale is set a few years in the future, when the interactive possibilities of a virtual human OS have been extensively developed, but you can recognize the OS here (who calls herself Samantha) as a lineal descendent of Siri.

Falling in love with an operating system has its limitations, obviously — only a fantasy form of sex is possible — but at first those limitations don’t seem so bad. Samantha has infinite patience, access to most human knowledge and develops genuine insights into Theodore’s moods and character, his man-boy passivity and fear masquerading as sensitivity.

Most importantly, Samantha knows how to “talk through” a relationship — she knows all the ploys and challenges and rewards, all the boundaries to be negotiated . . . and you begin to realize that this “talk” is the relationship, that the relationship’s only substance is this web of clichés that we have all been programmed to export and import on cue. It’s the kind of self-conscious talk that would make, and often enough does make, even a corporeal relationship bloodless, immaterial . . . an abstract proposition.

Theodore begins to understand this when Samantha introduces him to one of her other “lovers”, a virtual Alan Watts. This is the equivalent of that moment in a flesh-and-blood relationship when one partner discovers a route to a spiritual awakening which, unfortunately, will require some physical unfaithfulness to go along with it. (Watts was notorious for seducing his female devotees with highfalutin’ Zen platitudes about “personal liberation”.)

Meanwhile, as the Theodore-Samantha relationship runs its more and more painfully familiar course, Theodore finds himself thrown together with an old friend going through her own break up. She’s not as brilliant as Samantha, not as perceptive, not as stylish, not as eloquent — but she’s a real girl who needs a real boy . . . a relationship that isn’t created by talking about it, but by doing it.

By the end of this astonishingly wise and goodhearted film, you may feel you’re watching the first meeting of a new Adam and Eve — the boy and girl of the future who will have to rescue romance from the outdated code of standard relationship software, so predictable by now that even Siri will soon be able to imitate it flawlessly.

Click on the images to enlarge.

BOXING DAY

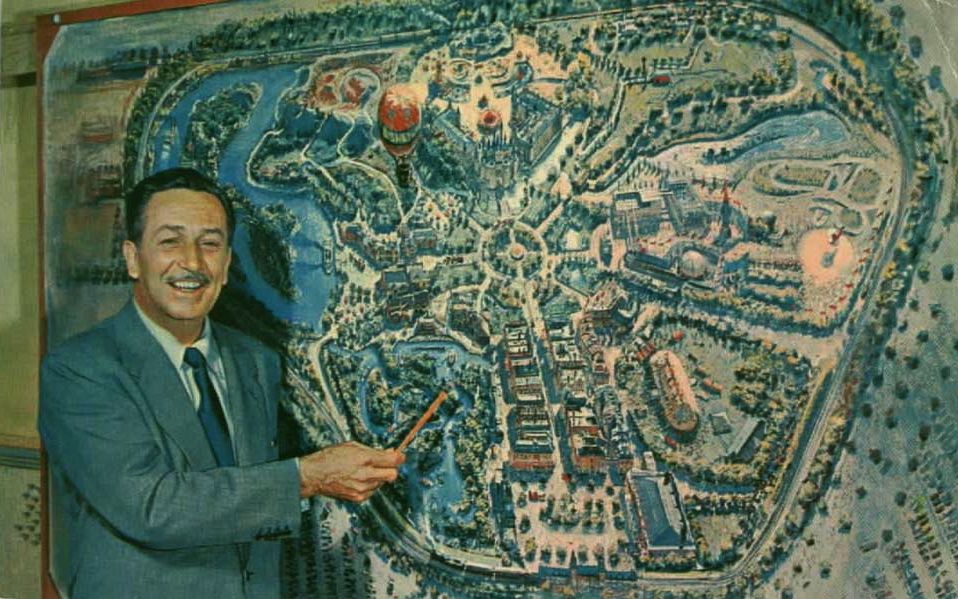

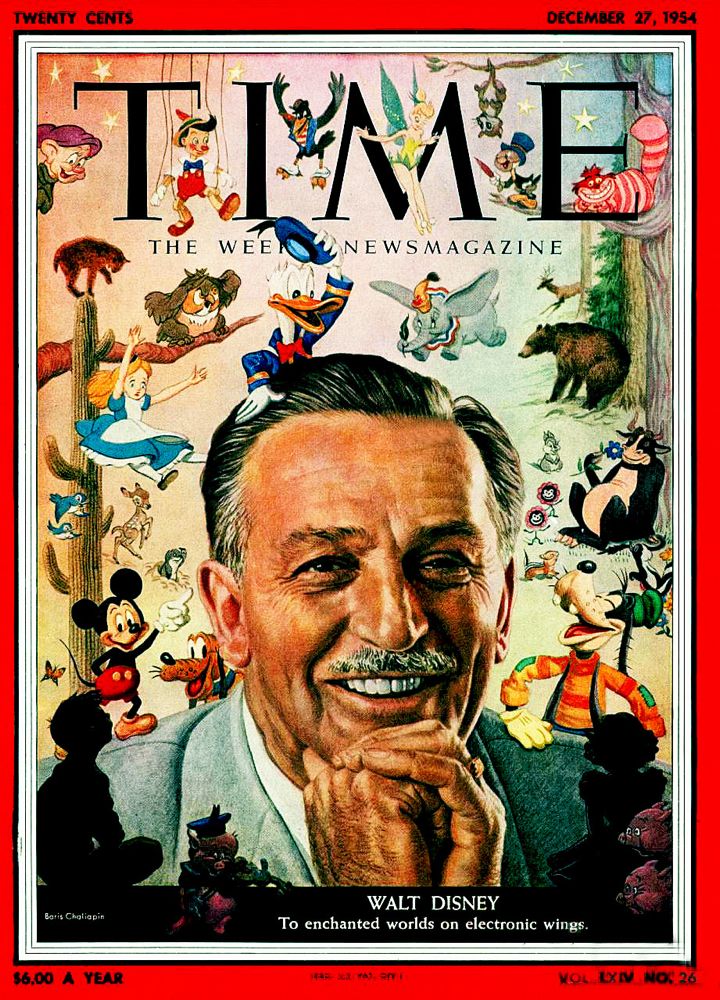

SAVING MR. DISNEY

There’s been a lot of criticism of Saving Mr. Banks as constituting a glorification of Walt Disney by the company he founded. The implication is that Disney doesn’t deserve glorification, and only gets it here through corporate puffery.

This is nonsense. Disney was one of the greatest artists, or artistic impresarios, of the 20th Century. He supervised the creation of some of the most sublime passages of cinema in the medium’s history. Here’s James Agee on some of the early Disney cartoons:

Do you ever happen to see any of the Silly Symphonies by Walt Disney? On the whole they are very beautiful. A sort of combination of Mozart, super-ballet, and La Fontaine . . .

The comparison with Mozart, with whom Agee associated Disney in other writings, is not farfetched.

Disney also revived Victorian spectacle theater, which had indirectly given birth to the movies, in his theme parks, creating, or recreating, one of the most vital if under-appreciated art forms of our time.

And Disney had balls bigger than those of any studio executive of his time. He was willing to take creative and financial risks that would have turned his peers to jelly. He certainly had balls bigger than anyone running a studio in Hollywood today, or ever likely to again.

Did Disney have a kind of middlebrow sentimentality? Sure. It was the middlebrow sentimentality of the audience that he, and most artists in Hollywood, sought to please. He still manged to create magnificent art within that limitation, as Dickens had before him.

Think what you will about Saving Mr. Banks — I found it fairly entertaining and occasionally moving — but don’t use it a pretext to patronize the genius of Walt Disney. One person of such genius in Hollywood today could redeem American popular movies.

Click on the images to enlarge.

A CHRISTMAS TREE FOR TODAY

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

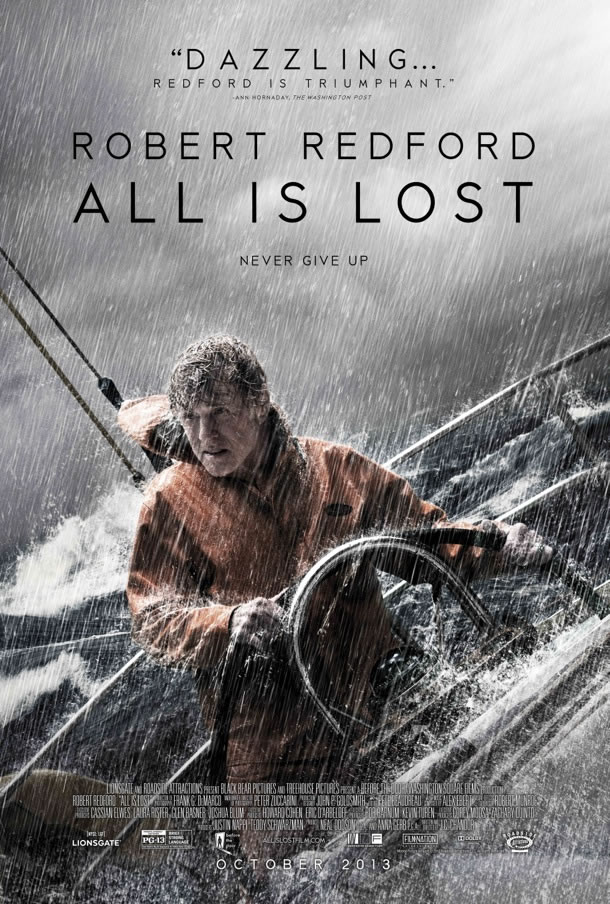

ALL IS LOST

This is not a terribly enjoyable film to watch — it’s harrowing and unsettling. It’s also extremely odd — a film with almost no dialogue. It’s about a sailor on a small boat in the middle of the Indian Ocean whose vessel receives a near-fatal injury, forcing the sailor to improvise a series of responses to the catastrophe in order to survive.

Things go from bad to worse — the sea does what it will with a sailor in distress. But the sailor keeps improvising, in the face of the worst the sea has to offer.

Robert Redford plays the sailor. Those who think that movie stars live or die by the dialogue they’re given need to look at Redford’s performance in this film. He has no dialogue — just a little voice-over speech at the beginning. And yet he’s consistently fascinating to watch.

Probably only an established star could have pulled off a performance like this — someone so confident in his or her screen persona that he or she is sure the audience will pay attention to the smallest details of eye movement, of facial expression. If Redford had overacted this part even a little it would have been a disaster.

So — no dialogue, grueling action on a tiny circumscribed platform, subtle acting . . . and yet the film is riveting. It’s a nautical procedural in which each procedure is invested with suspense, a kind of dogged, stoic heroism, and what Yeats called “the fascination of what’s difficult.”

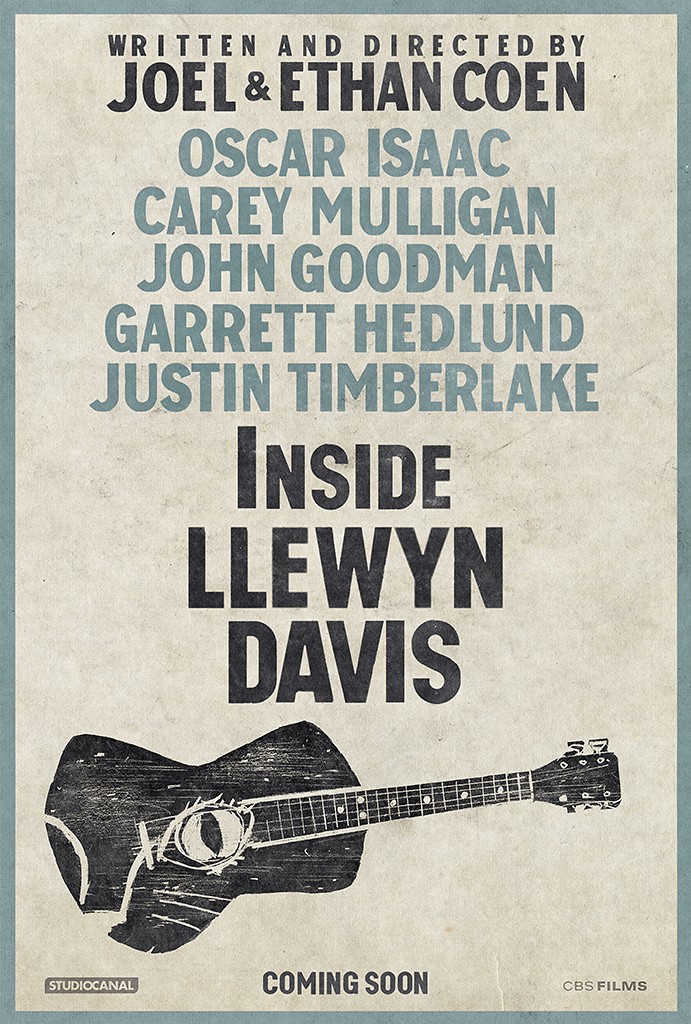

INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS

There’s a line in a Bob Dylan song — “I know plenty of people put me up for a day or two” — that perfectly sums up everybody’s scrambling days, when you were between fixed abodes, between relationships, between steady jobs, between plans, between dreams . . . when you wore out every welcome you received because you didn’t know where the next welcome was coming from, when you were too proud to go home to mom and dad (and maybe you’d worn out their welcome, too), when you just didn’t know what the fuck you were going to do next.

When you’re young you figure such days will pass, and they usually do, after a fashion, but you never really get over them. Inside Llewyn Davis is about such days in the life of a struggling folksinger in New York in the early 1960s. Its evocation of that time and place, that musical scene, is magical, but it’s the evocation of Llewyn’s scrambling life that makes the film memorable.

It’s not one of the Coen brothers’ most inspired efforts — the litany of Llewyn’s woes gets a bit repetitive after a while. Once you realize that nothing is going to turn out well for Llewyn the narrative loses momentum. And yet . . . Inside Llewyn Davis gets at something, portrays something, that few films ever have.

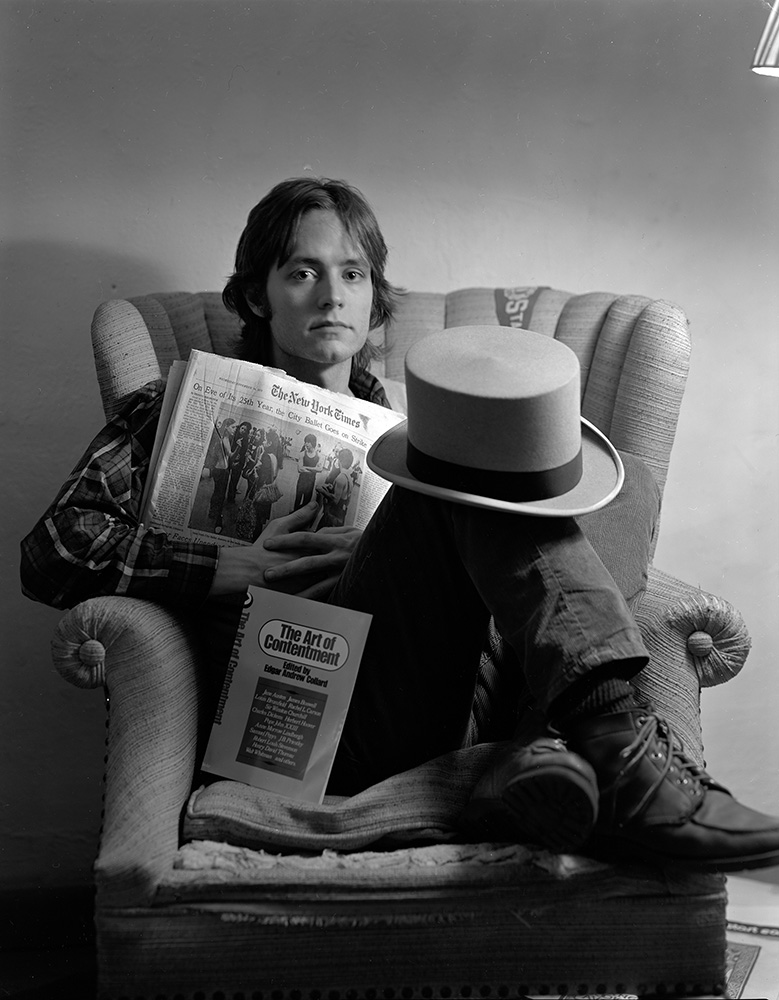

[Image © Langdon Clay]

I spent many of my own scrambling days in New York in the 70s so the film brings back poignant memories, and a curious personal revelation. I got all, or almost all of the things I dreamed about getting in the 70s and one by one they have all evaporated or come to seem hollow — and I feel today more like that scrambling kid in his 20s than I ever have since the 70s. With one difference — I’m no longer looking for a home in this world, I mean, one that I can rely on. I know that all homes are provisional, as provisional as sleeping on a couch in a friend’s living room.

So it’s heartbreaking to see Llewyn Davis’s heartbreak as he looks for a home, a place for himself. I want to slip him 20 bucks and tell him not to worry — tell him that he’s already as home as he’ll ever be, that life is a perpetual scramble, and worth the discombobulation. Not that he’d listen, anymore than I would have when I was in my 20s.

Click on the images to enlarge.

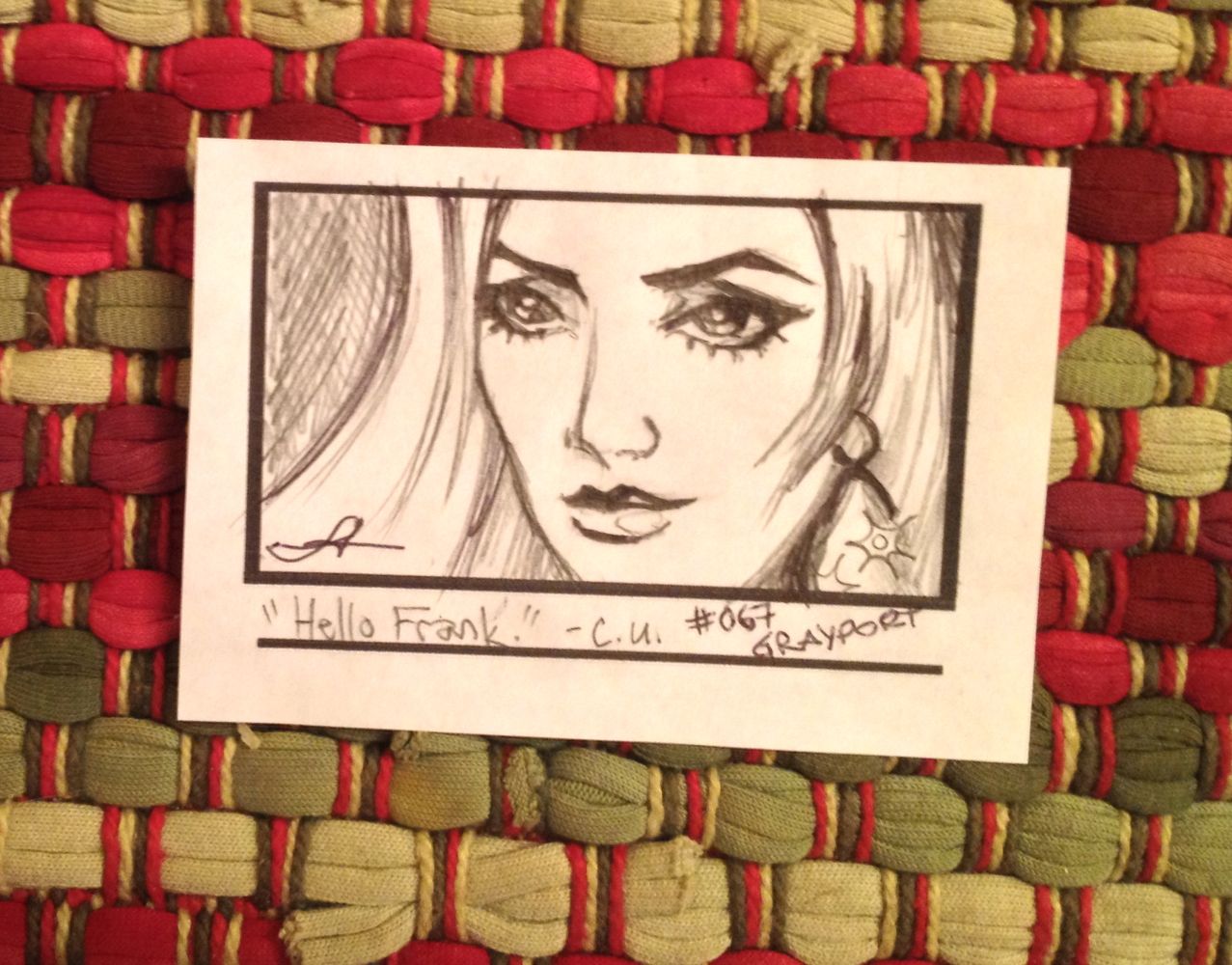

LOOK WHAT I JUST GOT

. . . original storyboard art for the upcoming indie film Grayport, one of the Kickstarter rewards for a modest $25 contribution. Get yourself one here:

Click on the image to enlarge.

NEBRASKA

I must say I embarked on a viewing of this film with some trepidation. I’ve always thought of Alexander Payne’s films as “watchable” — and if that sounds like damning them with faint praise, well, that’s the idea. They are films with interesting premises set in interesting places and employing interesting actors but don’t add up to much more than a couple of hours of diversion.

Noting that Nebraska was shot in black and white, I feared that Payne had at last decided to make a full-on art film, which I expected to be pretentious and dreary — but Nebraska is neither of those things. It’s a modest, well-observed, beautifully shot movie that doesn’t condescend to its quirky heartland characters and their relentlessly flat world. Instead it takes them seriously, or as seriously as they deserve to be taken, and it loves them, without judgment.

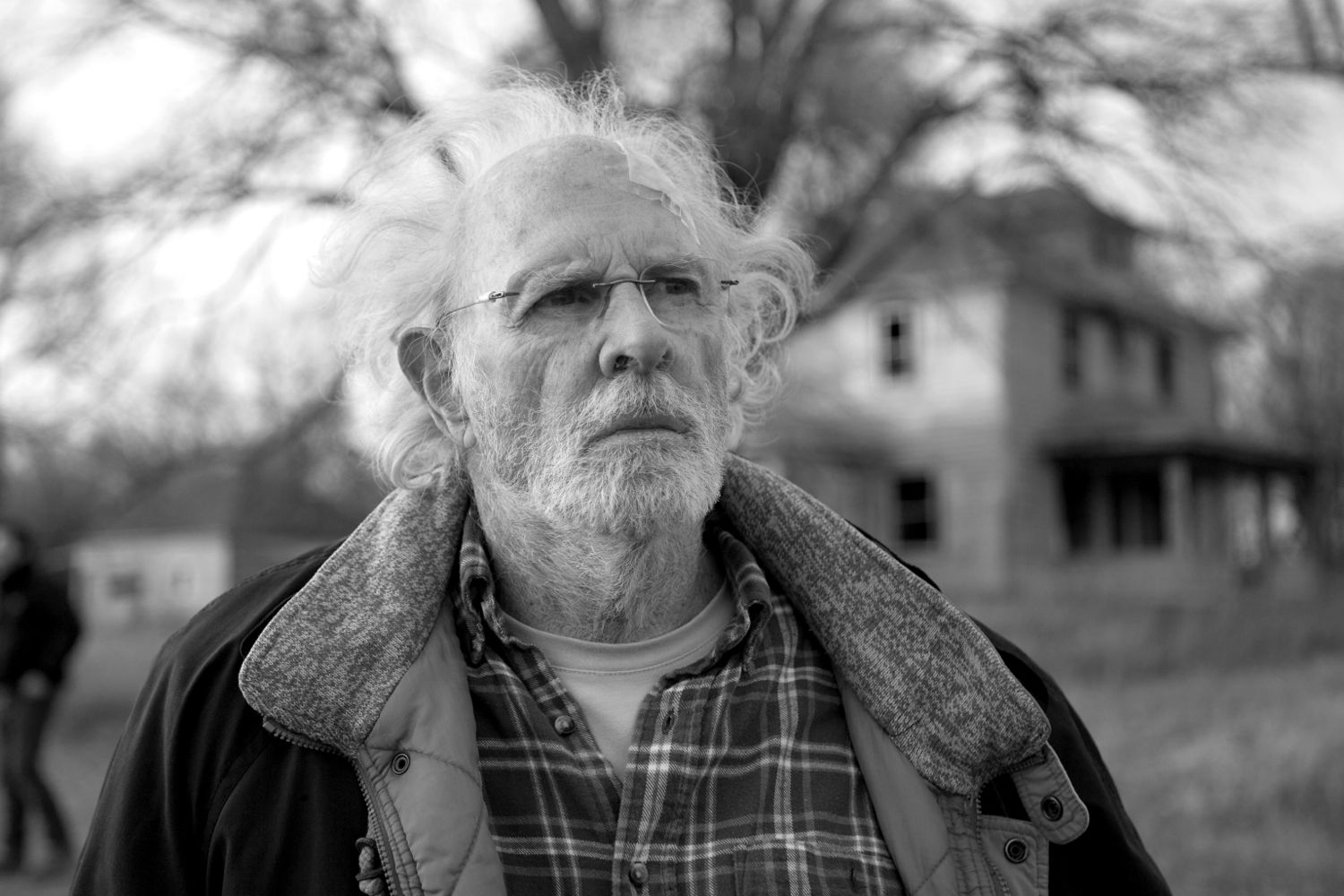

Bruce Dern’s performance sums up what’s good about the movie. Dern is so deep inside the buttoned-up character he plays that he reveals no more about himself to us than he does to the people around him. What might have been a showy caricature of old age becomes instead a moving portrait of estrangement and bewilderment. Dern creates this portrait basically by doing nothing, by reacting blankly to the revelations about his life that the film delivers.

We can read what we want to or need to into his taciturn persona but Payne never prods us into anything. We’re allowed to be amused by the simple-mindedness of some of the characters we encounter, but Payne never patronizes them.

This is the sort of odd, personal, adventuresome yet circumscribed movie that used to get made with some regularity in the 70s. It isn’t a great movie by any means, but it’s an admirable and humane movie — a great rarity on the current scene.

ZOEY’S GUIDE TO REAL LIFE

Matt Barry’s latest — modern youth on the march . . . not.