PZ offers some thoughts on a novel and a film that have been regularly misunderstood, or at least mischaracterized:

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit

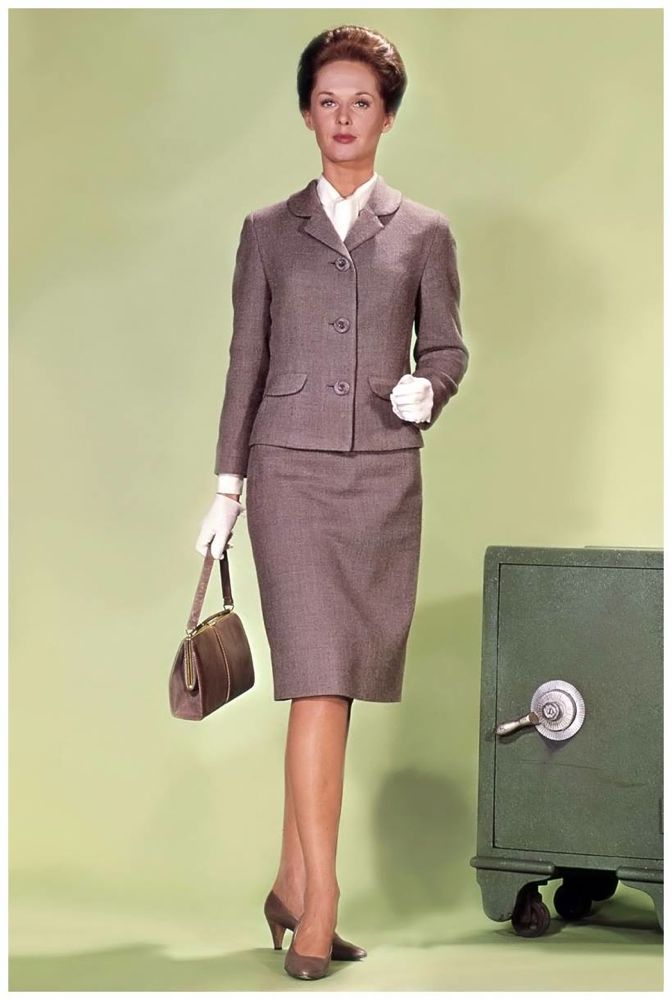

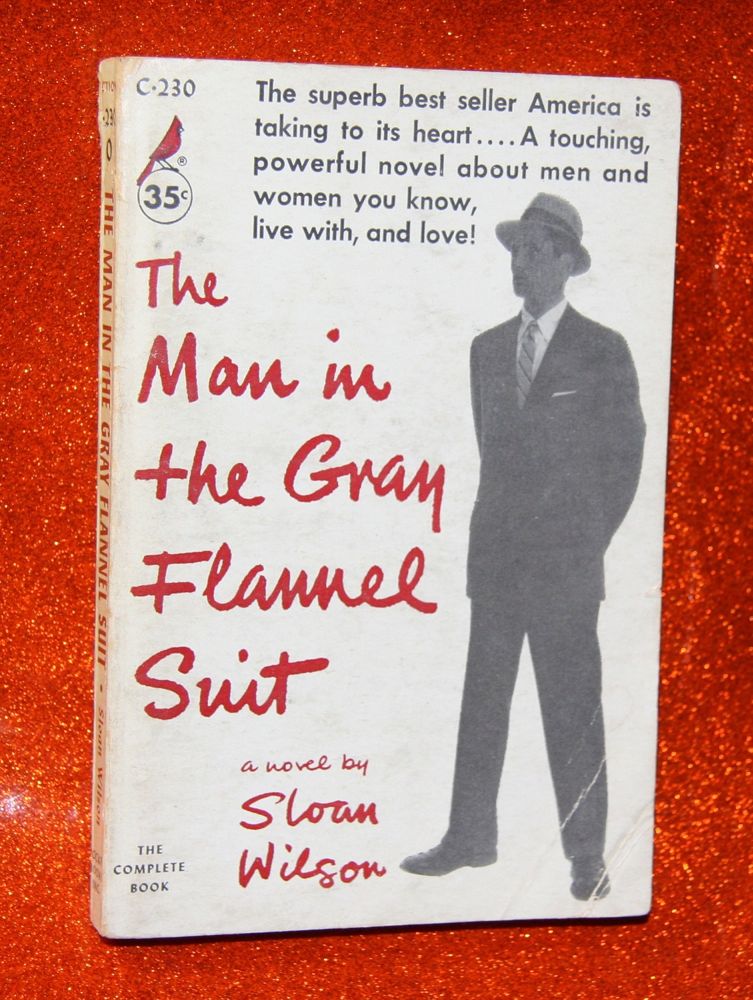

This is an interesting movie (1956) and a very interesting book (1955). Sloan Wilson, a master novelist who understood marriage and men, wrote the novel. Darryl F. Zanuck produced the movie, and Nunnally Johnson scripted it and directed it. It starred Gregory Peck and Jennifer Jones.

I was drawn to the novels of Sloan Wilson in the aftermath of a personal trauma,

for, come to find out, Wilson’s characteristic protagonists are men who are trying to find themselves in the aftermath of a shock. Wilson is not in fact the portraitist of 1950s “suburban conformity”, which is the usual critics’ tag attached to his work; but rather, a portraitist of men who live in the aftermath, as Wilson himself did, of trauma. His heroes are usually early middle-aged “Everymen” who have seen disturbing action in wartime and are trying to re-adjust their lives to “account” for what they have been through.

Tom Rath, the gray-suited Westport commuter of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, is carrying inside himself absolute shock at the things he had to do in France in l944 and the losses he suffered in the Pacific right after that. No one knows this about Tom Rath — he is taciturn and diffident, like many survivors of that war. Not even his wife knows. There is another aspect, too, of his time overseas that returns to haunt him. Nothing can be compartmentalized, even on the New Haven Line.

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit is a truly explosive novel and movie, nuclear but also abreactive. It is not about conformity. It is about engaging pain. Fortunately, Tom and Betty Rath do engage the pain. They are enabled somehow to go into it, rather than shy away from it. They are literally saved by a kind of confrontation with their suffering. Their story is almost ennobling.

When you think about the Eisenhower years, or if you have experienced a trauma since the Eisenhower years — like maybe last week — you could learn from Sloan Wilson. You could get something out of quiet Tom and not-so-quiet Betty Rath. Life’s acuteness forces them to go towards, not suppress and flee — like my own tendency, for example. It is not exactly “fight or flight” in the Raths’ case. But it’s certainly not flight.

While you’re at it, read Sloan Wilson’s Georgie Winthrop (1963) — the year of the Great Event we’ve been recently remembering. Poor George Winthrop. He is not allowed off the hook either. But he comes into something, too. Something good. Or at least, survivable.

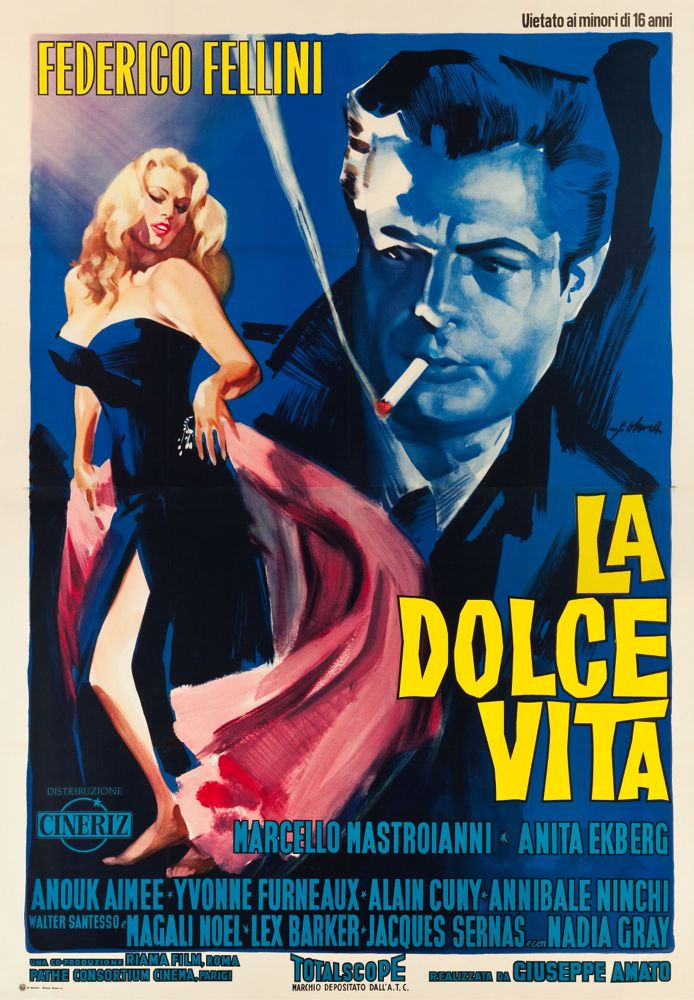

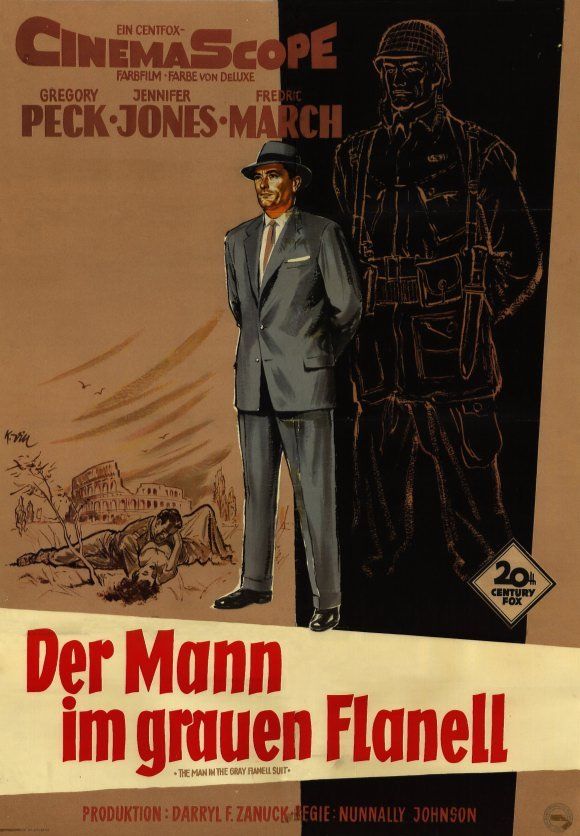

[PZ also points out a telling difference between the U. S. and the European advertising art for the film. In the German poster above, the context of the tale is emphasized by the ghost of the soldier he once was standing behind and towering over the figure of Peck. In American advertising art, this ghost figure did not appear. This suggests that American audiences would not have been immediately attracted by an image of PTSD haunting returned American soldiers. That subject had to be treated obliquely, in the guise of crime thrillers, for example, in the film noir tradition, or in the guise of a tale about “suburban conformity”.]