Click on the image to enlarge.

Category Archives: Movies

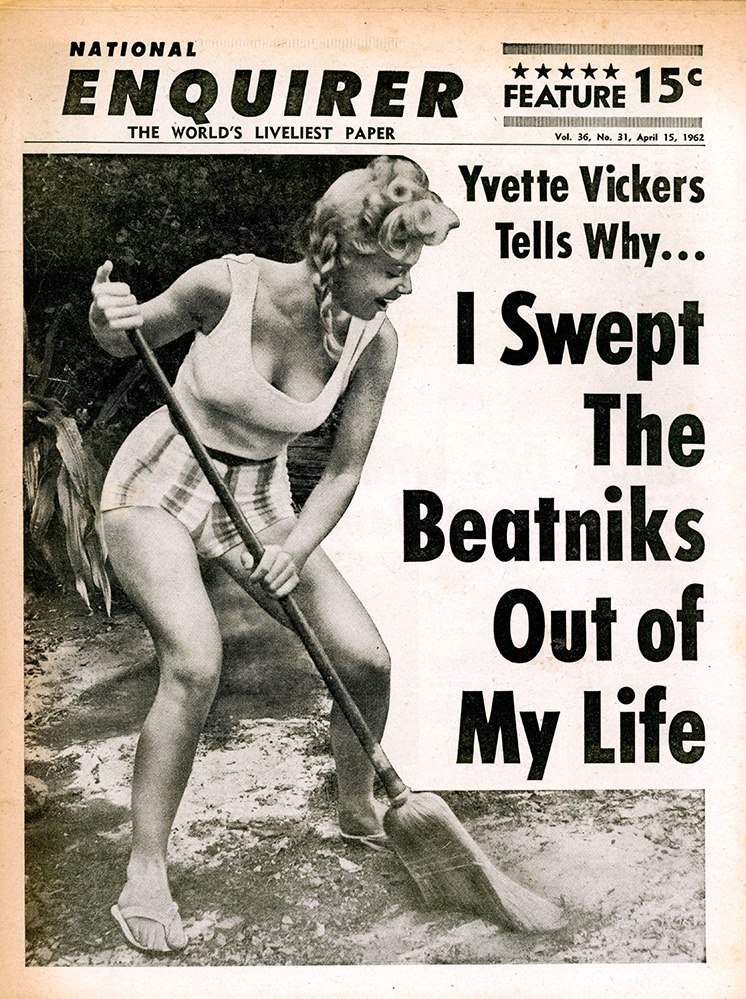

A TABLOID NEWSPAPER COVER FOR TODAY

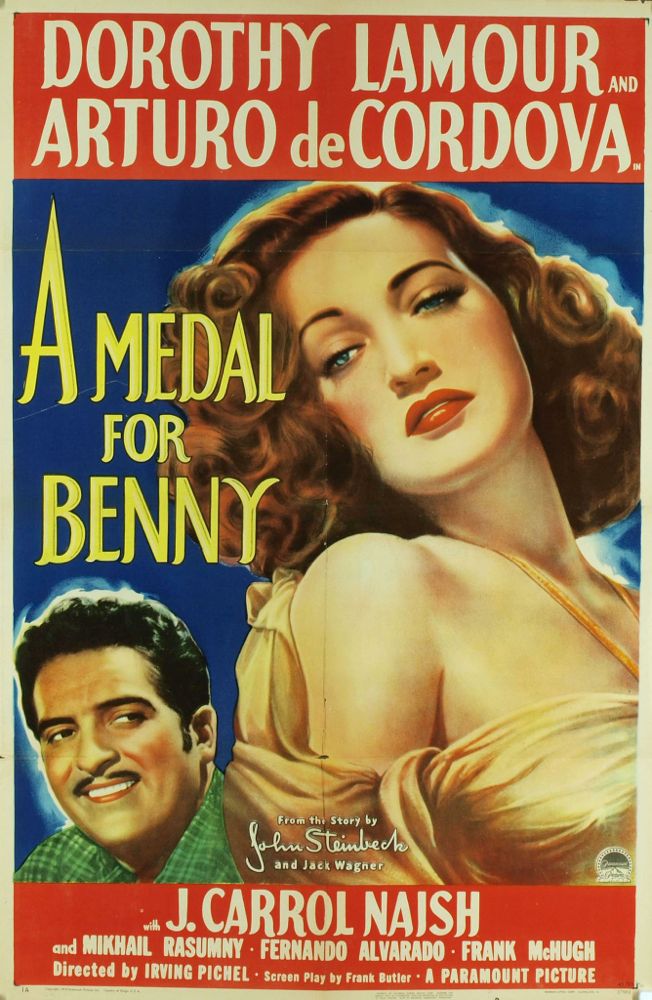

A FILM POSTER FOR TODAY

FRANÇOISE

HOUSEHOLD GODS

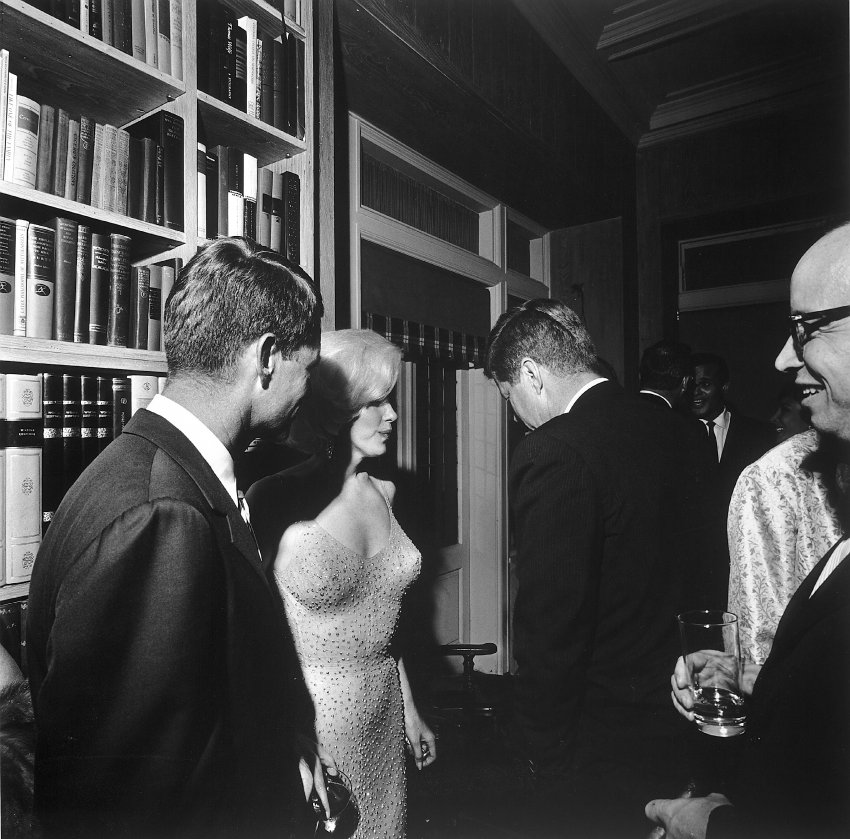

MARILYN

LLOYD’S MODERN LIFE: FROM THE TERRACE

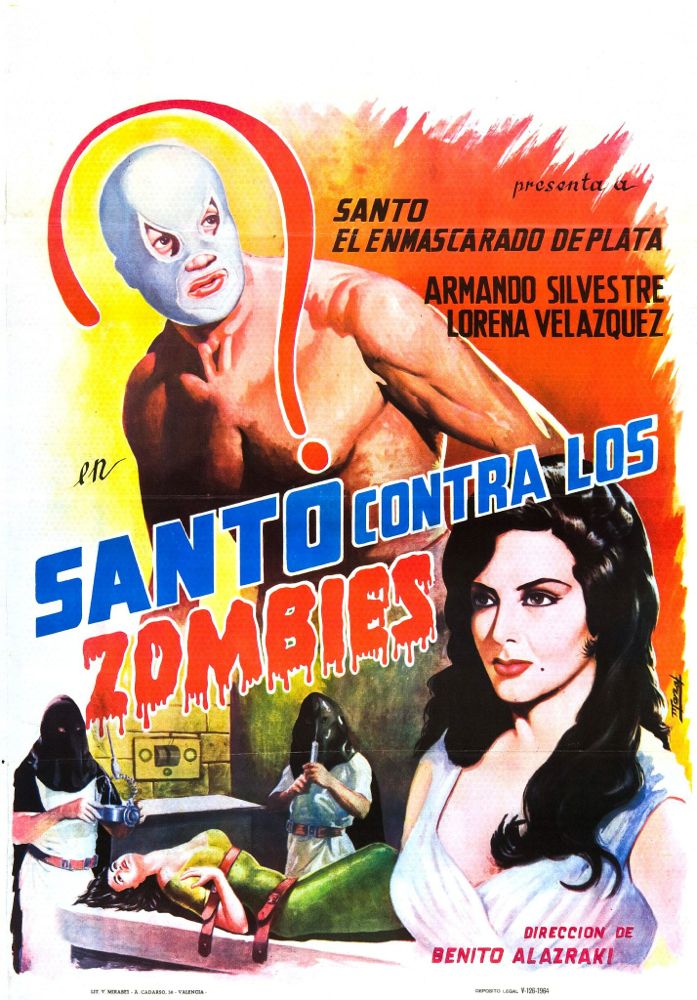

A MEXICAN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

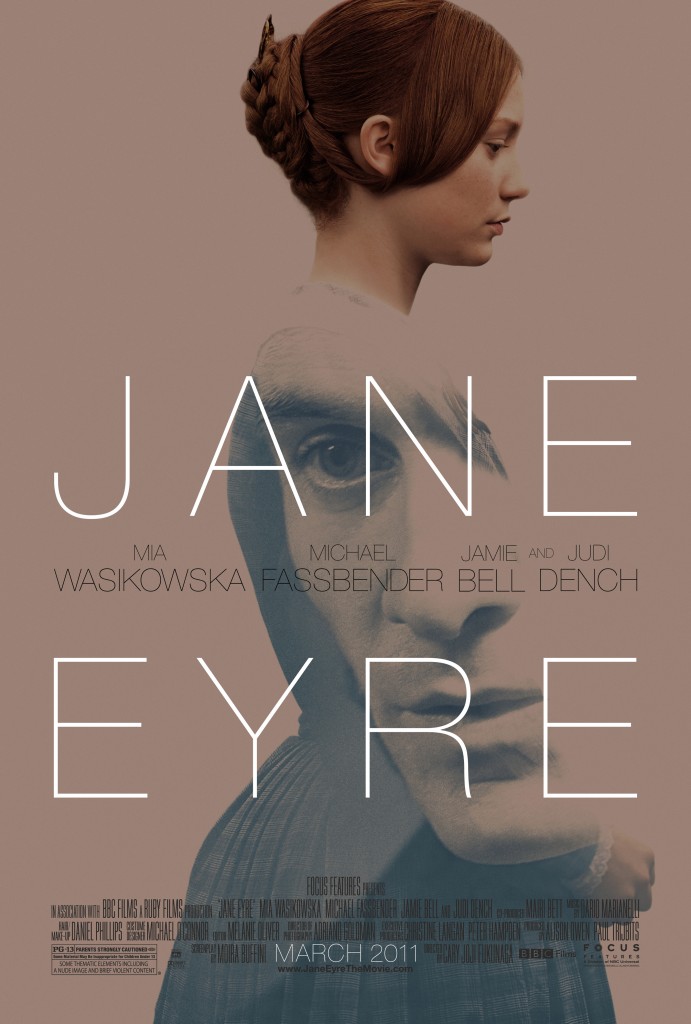

JANE

A few nights ago I watched Cary Fukunaga’s 2011 adaptation of Jane Eyre and I can’t stop thinking about it. It’s not a perfect film but it’s brilliant in many ways, and a number of them derive from the script by Moira Buffini.

As my friend Ron Salvatore has noted, it must have been very tempting to portray Jane as a modern-day feminist trapped in a corset, but any attempt to do that, to associate her independence with any form of modern ideology, would have robbed Jane of her prime virtue — the fact that she is a woman who figures things out for herself.

In fact, Charlotte Bronte and Jane base their claims for female equality on an inner faith in themselves as individuals, and justify that faith on religious grounds. It’s easy to forget that the true roots of modern feminism lie in the Protestant Reformation, and its insistence that each soul, male or female, is responsible for its own salvation. (Not responsible, it must be noted, for earning its own salvation, since in core Protestant theology salvation can’t be earned, but responsible for accepting the salvation offered as a gift by God.)

This doctrine led directly to the Protestant disapproval of arranged marriages, on the grounds that it was an individual woman’s responsibility to marry a godly man, even in defiance of her family’s wish to the contrary. This caused a social upheaval which is evident in art as early as Shakespeare’s plays, which deal repeatedly with conflicts between fathers and daughters over issues of marriage, with Shakespeare invariably endorsing the rights of the daughters.

Buffini does not shy away from the now utterly uncool religious foundation of feminism. She follows Bronte in the moment when Jane makes her case for equality with Mr. Rochester, as follows:

Am I a machine without feelings? Do you think that because I am poor, obscure, plain and little that I am soulless and heartless? I have as much soul as you and full as much heart. I’m not speaking to you through mortal flesh . . . It’s my spirit that addresses your spirit as if we’d passed through the grave and stood at God’s feet, equal — as we are . . . I am a free human being with an independent will, which I now exert to leave you.

This is Jane speaking from the depth of her being as a person of faith — she believes that her right to equality and independence is a gift from God, just as the signers of the American Declaration Of Independence did.

But, as with those signers, Jane’s equality and independence are things she feels inherently — they constitute a truth which she holds to be self-evident. Who knows how many women of Jane’s time felt the same? Jane’s heroism lies in the fact that she has the courage to speak of it openly, defiantly, without regard for consequences.

And this is the key to the genius of Fukunaga’s film, and to Mia Wasikowska’s exceptionally fine performance as Jane — they show us the mind of Jane at work behind the level gaze, they convince us of her faith in herself and in God.

What they give us, in fact, is a real woman on screen — a woman who exists independent of male desire and male control, a woman who is responsible for her own soul. This is all but unique in modern movies — at least since Rose, old Rose and young Rose, in James Cameron’s Titanic. All the other examples I can think of involve much younger females, Mattie Ross in the Coen brothers’ True Grit, Suzy Bishop in Moonrise Kingdom, Hush Puppy in Beasts Of the Southern Wild.

But Wasikowska’s Jane is a mature woman, and the fierceness of her individuality and will has a decided erotic quality, which works on us as it works on Mr. Rochester. In her bastions of Victorian drapery, she is far more vexing than the half-clothed cartoon women who titillate male vanity in most modern movies. We become convinced that there is a real woman beneath all that drapery, behind all that circumspect locution — and we are reminded how sexy a real woman can be.

SO LONG, ‘DOBE

MOVIE COWBOY

HORRIFYING CHRISTMAS ANIMATION

. . . not for small kids.

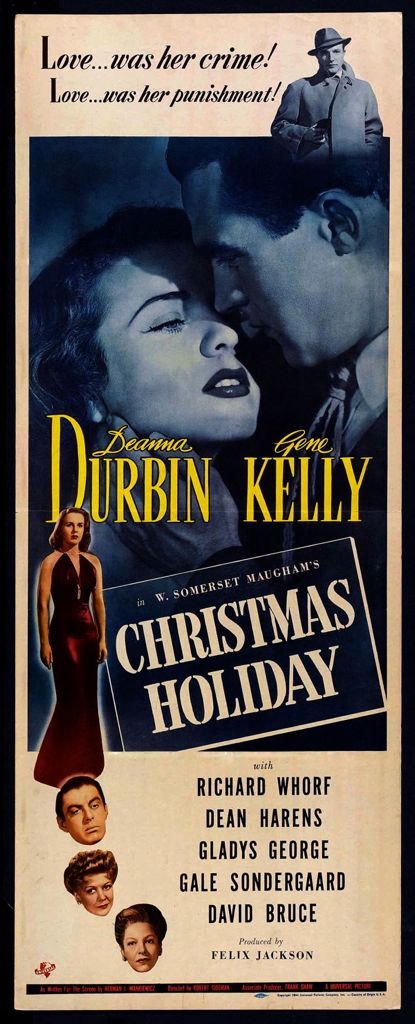

A MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

CAROL FOR ANOTHER CHRISTMAS

Paul Zahl weighs in with some seasonal thoughts about a TV show written by Rod Serling:

CHRISTMAS COFFEE WITH ROD SERLING

Anyone who likes Christmas has got to like Rod Serling. Serling was no Grinch! In fact he liked Christmas so much that he wrote two Twilight Zone episodes about Christmas, and one Night Gallery episode.

The gem of gems, however, if you like Christmas and also like Rod Serling, has got to be his 1964 teleplay Carol for Another Christmas. I’m a person who has been living for seeing this one ever since word came out that TCM was going to air it this Christmas. Twice, in fact!

Can I talk a little about the visuals of this counter-cultural television show — counter-cultural in l964 and still counter-cultural today? It was shot in New York City and directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who also produced it. It tells the Christmas Eve story of the redemption of a rich and powerful WASP refugee from James Gould Cozzens country,

a man with a big grudge against life. His name is “Daniel Grudge” and he is played by Sterling Hayden.

The vehicle, you might say, for the redemption of Daniel Grudge is a round-the-world tour, for embittered Mr. Grudge, of the past, the present, and the future of war. He is required to take passage on a World War I troop ship transporting the coffins of war dead. He is required to visit the victims of Hiroshima, all young girls, who have lost their faces. (In a typical Serling subversive touch, the voice of conscience is a Southern American blonde WAVE, played by Eva Marie Saint, who tries to get through to the hard Yankee “Grudge”.)

The hero is then required to spend time in a Communist gulag for prisoners of all ages and races, where they are singing Christmas songs in Russian, tho’ Serling is quick to show prisoners who “do not celebrate Christmas”.

Finally, “Mr. Grudge”, as Serling characteristically calls him way too many times, has to sit through a rally with the “Imperial Me”, played by Peter Sellers, in a bombed out meeting-house in his own hometown, where the few survivors of a nuclear war gather to become even more savage than before. This is Daniel Grudge’s Christmas Future.

The expressionist visual style of the show is powerful, especially in the gulag scenes, the “Imperial Me” scenes, and at the quiet and soft finish to Carol for Another Christmas. At the end, Mr. Grudge is just sitting there, having coffee with his African-American servants — they won’t be servants much longer — and listening to Christmas Carols on the radio. I think the very leisurely close of the piece is an interesting artistic decision. After all the talk — and there is plenty of Rod Serling talk, especially in the first third — the last scenes of the play are quiet.

We do find out that “Nephew Fred”, played by Ben Gazzara, is on his way to church, and we also hear church bells outside across the snow. But otherwise it’s just Sterling Hayden, drinking and actually savoring a long cup of coffee, with the radio on in the background, playing carols.. Anti-climactic? No Tiny Tim? Well, maybe. But it’s still moving.

A final note:

As my wife Mary and I watched Carol for Another Christmas, we both thought this: Rod Serling seemed to see Christmas as a uniting and reconciling celebration rather than as a divisive power. The script constantly speaks of “peace on earth, good will to men” — the “Brotherhood of Man”. Fascinating — Christmas as a word of unity to the family of man, no matter what your creed or specific beliefs. Apparently it was not a problem for the writer and the producer/director of Carol for Another Christmas. Both artists were ethnically Jewish.