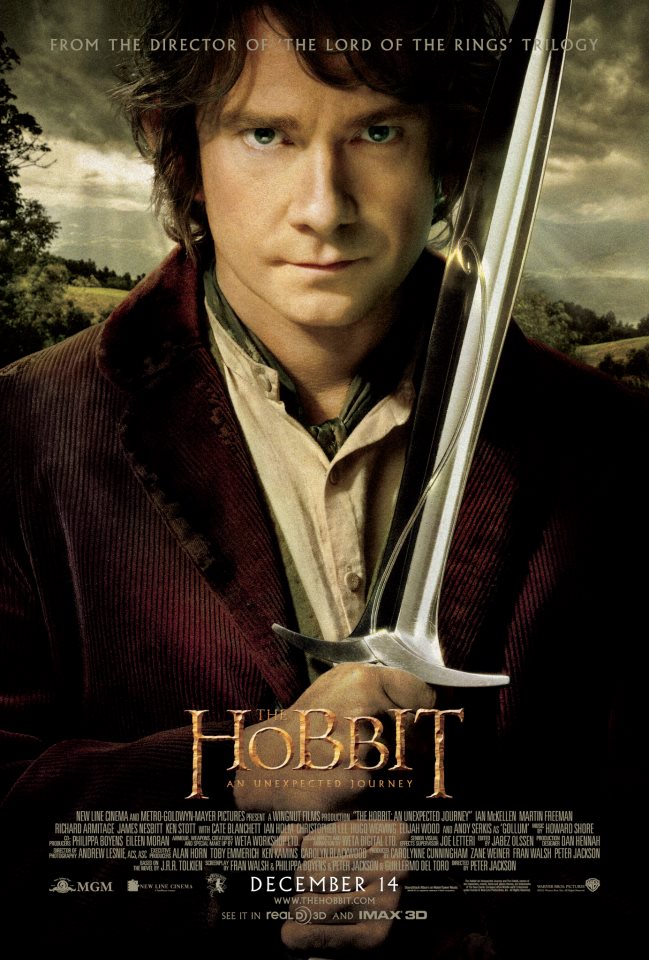

You could, with some justice, dismiss this latest of Peter Jackson’s Tolkien movies as self-indulgent, guilty of inflating modest story content to immodest lengths — or you could just adjust your sensibility to Jackson’s leisurely narrative pace, go with it and see where it takes you. I would suggest the latter course.

There’s plenty of movie magic in the film to divert you, and while none of the images is as exciting, inventive or lyrical as some of those in the Rings trilogy, they’re good enough to keep you attentive.

But neither narrative momentum nor movie magic explains why this film is so easy to love, why audiences are flocking to see it. The film’s chief attractions are moral — it celebrates the value of simple decency in a horrifying world. It celebrates characters who treasure “loyalty, honor and a willing heart” above all other things.

Loyalty, honor and willing hearts are in short supply among our leaders these days, and among our pop culture icons — they are virtues that seem almost pathetic in the context of modern life, the attributes of losers. But in Middle Earth, they conquer, they rule, against all odds, and people are hungry to see that triumph of simple decency, even in a fairytale land.

We are frightened these days, as Gandalf is frightened of the dark forces gathering at the edges of his world, and the common decency of Bilbo Baggins gives us heart, as it gives Gandalf heart.

It is the genius of Gandalf, and of Peter Jackson, to understand the character of Bilbo as a specific against despair. It’s what makes them both powerful wizards.