Category Archives: Movies

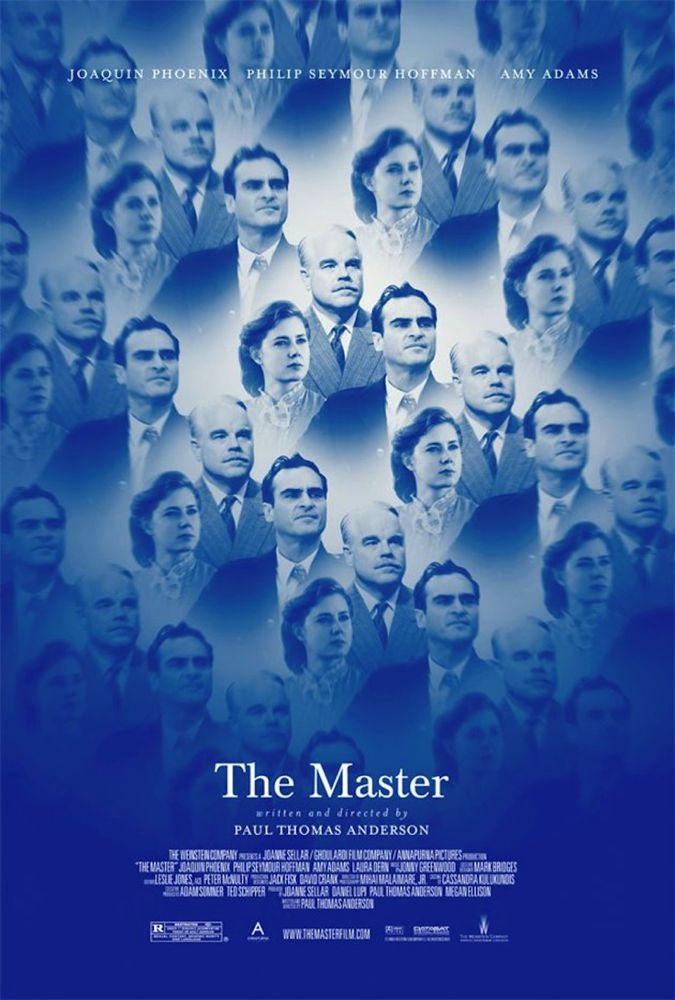

THE MASTER

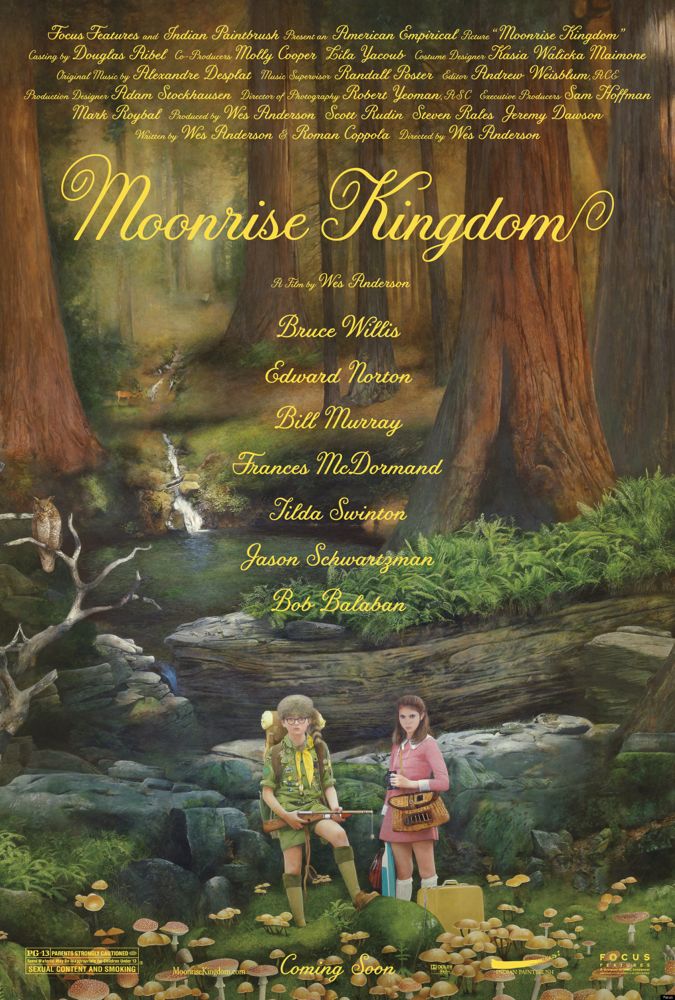

MOONRISE KINGDOM

I’ve never thought much of Wes Anderson’s films. They always struck me as eccentric but tepid — films that took on emotional subjects in cute tones that avoided any actual emotional engagement.

Moonrise Kingdom is different. It celebrates an anti-cynical view of romance in emotionally convincing terms. It’s a period film, set in 1965, and it’s conveyed in a cute deadpan style, but its heart is with its innocent lovers absolutely — so absolutely that it achieves more than a few moments of genuine poetry.

Anderson has finally found a tale in which he can reconcile his hipster hauteur with his romantic inclinations, and the result transcends hipsterdom entirely. This is probably as close as a cool modern filmmaker can get to genuine romance, but it gets very close indeed.

Is it possible to imagine a contemporary movie romance like this between lovers who are older than twelve? It would be nice to think so, but I’m not holding my breath . . .

Click on the images to enlarge.

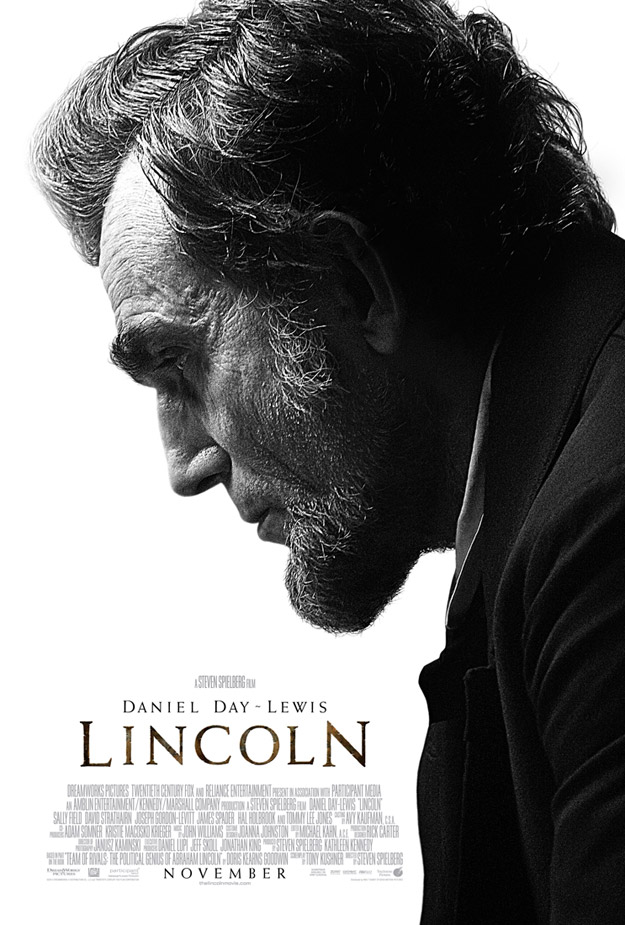

LINCOLN

The trailers for Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, and the poster above, which depicts the man as a kind of bas-relief sculpture, suggested that the film was going to be a chore to get through — a pious civics lesson about the martyred saint who freed the slaves and saved the Union.

In fact, the film is quite entertaining, thanks to Tony Kushner’s lively and intelligent screenplay and a number of very good performances, by Daniel Day Lewis, Sally Field and Tommy Lee Jones in particular. Lewis’s interpretation of Lincoln is the best of all those that have been done in movies, simply because he makes Lincoln seem like good company, as by all contemporary accounts he was. This is something even Henry Fonda, likeable as he was as a screen presence, couldn’t quite pull off except in brief moments.

The film takes a brutal look at the mechanics of American democracy, at the skulduggery and corruption that grease the wheels of even the most idealistic legislative achievements. This is paralleled by a visual evocation of the shadowy and grimy physical world of the 19th Century — you get a sense from watching this film of how bad most people of that time probably smelled.

The film fudges a bit on Lincoln’s views about integrating freed blacks into American society as citizens — he probably wasn’t as sanguine about the prospects of that, as open to the idea, as he’s presented here. On the other hand, it’s fair to suggest that his thinking on the subject might have evolved had he lived longer — that there were the seeds of such an evolution in his heart.

What’s less forgivable about the subtext of the film is the suggestion that the questionable legal and moral tactics Lincoln used during the greatest crisis that ever faced the nation, a time of armed conflict on a massive scale, might be applicable to our own current President, whose legal and moral transgressions against the Constitution and liberty itself haven’t unfolded in a similar context.

I don’t think there’s any doubt that Kushner and Spielberg had some such apology for Obama in mind when they made this film — and wanted to imply that noble intentions can justify almost any act by a President. That’s a stretch — and a dangerous one.

ON THE SET

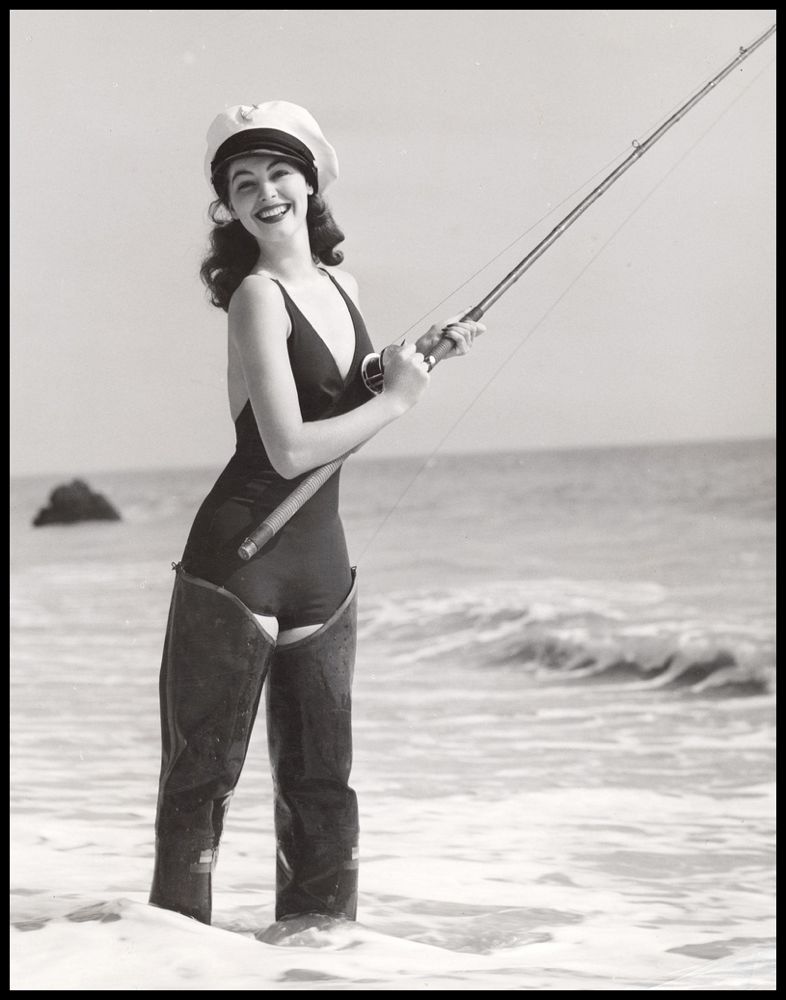

A LOBBY CARD FOR TODAY

ESSENTIAL

Meet Me In St. Louis joins my list (along with The Searchers and Rear Window) of Blu-ray editions that belong in every home — that are in themselves worth buying a Blu-ray player for.

Meet Me In St. Louis is one of the greatest of all Hollywood musicals, and one of the greatest of all movies. It grows deeper and more astonishing with each viewing. If this film doesn’t make you cry, you need to totally reexamine your life, your values, your sense of what the world is really all about.

Producer Arthur Freed was the driving force behind getting the film made at MGM. Most of the other executives at the studio strongly opposed it — they didn’t think it was about anything, not understanding that the dysfunctional moments of a happy family is a subject of the most sublime profundity.

Louis B. Mayer intervened and told Freed to go ahead with the production, saying, “Either he’ll learn something or we’ll learn something.” The result was the most profitable film in MGM’s history, beating out even Gone With the Wind, which MGM only owned part of.

Gene Kelley said it was his favorite musical, and Martin Scorsese lists it among the films that most influenced his visual style. It’s an absolute miracle — especially on Blu-ray, where it’s possible to more fully appreciate director Vincente Minnelli’s elegant exploration of the house at the center of the film, and the choreography of the family members within it which reflects the shifting elements of the family dynamic.

Click on the images to enlarge.

DIETRICH AT THE FRONT

A MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

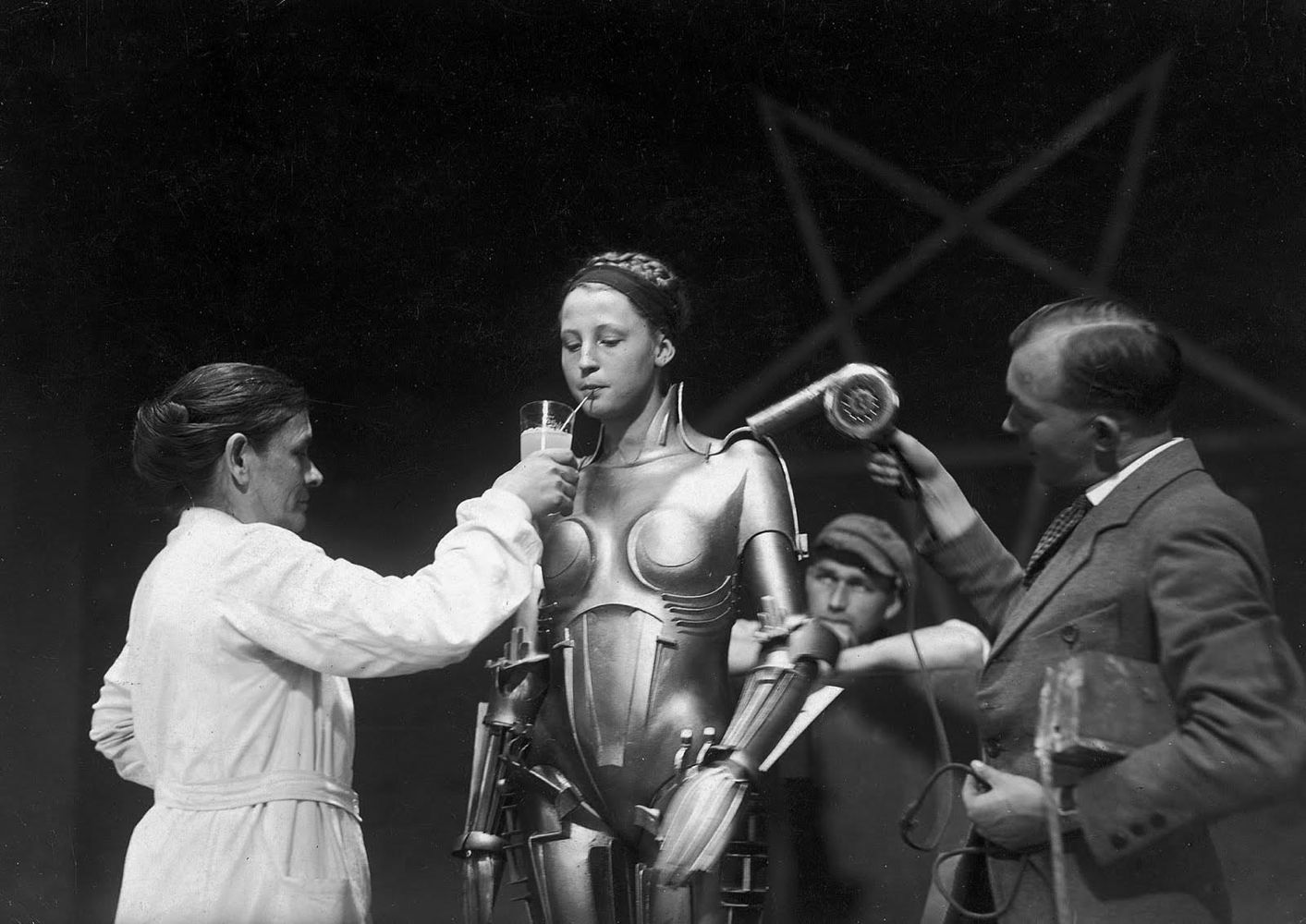

ON THE SET

VENUS

HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS

A HOLIDAY WREATH FOR TODAY

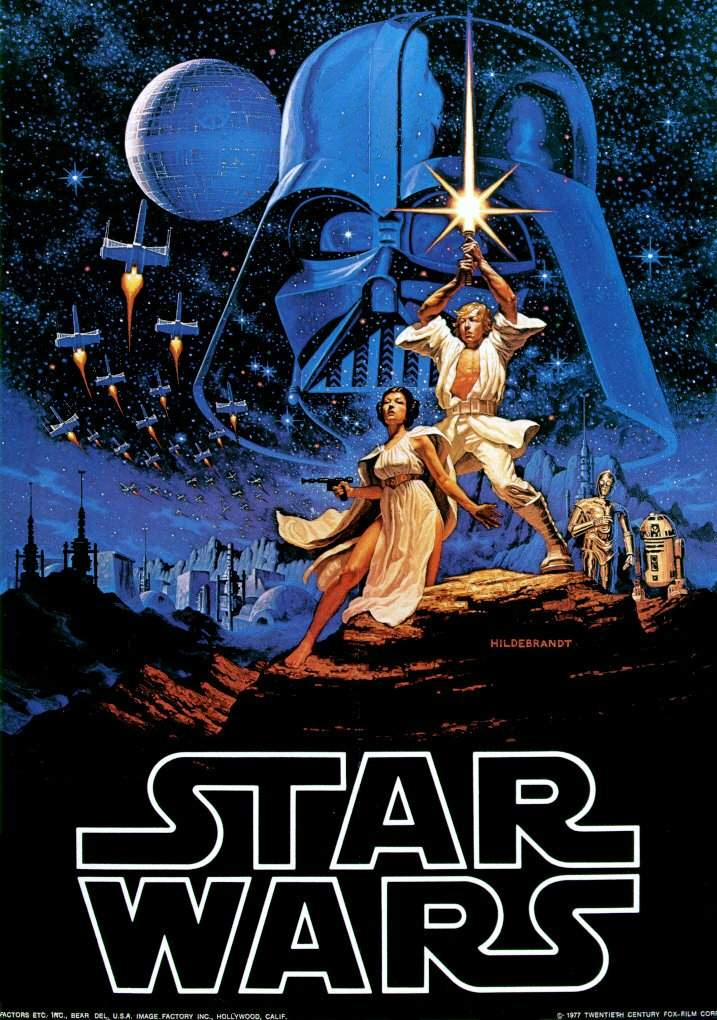

STAR WARS

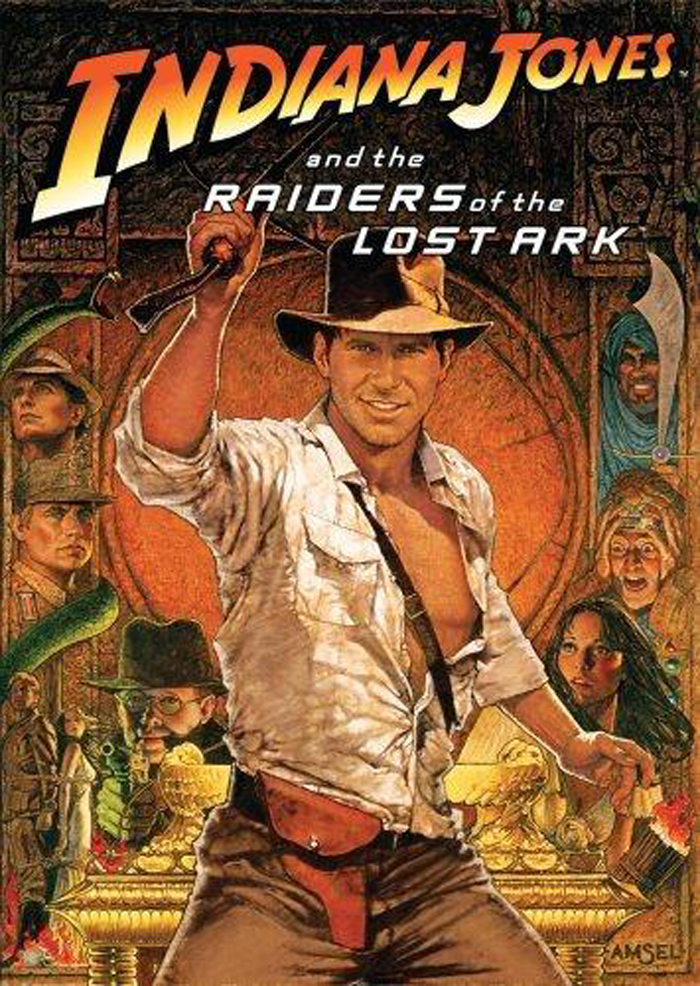

The first three Star Wars movies, like the first Indiana Jones movie, were the products of a brilliant conceptual leap. Lucas and Spielberg decided to makes films based on the B-movies they loved as kids but in a different register — with the magic they remembered from their childhoods but treated with the wit and visual poetry they were capable of as adults.

They thus delivered this remembered movie magic out of the realm of nostalgia and made it new and alive for modern audiences — and for themselves, too, undoubtedly. They didn’t copy the old films that had once so inspired them — they recreated them not as they were but as they remembered the experience of seeing them for the first time.

It’s too bad in a way that the Star Wars films were so successful, became such a cultural institution, because they outlived as a phenomenon and as a commercial property the impulse that led Lucas to make them. When he came to make the second Star Wars trilogy, prequels to the first, he seemed to have lost touch with the imaginative roots of the first three films . . . he seemed to be trying to recapture the creative thrill of making those first three films, not the childhood memories that gave birth to them.

In a curious paradox, the second trilogy became actual B-movies, a recapitulation of the re-imagined formulas of the first trilogy — exercises in nostalgia for films that had transcended nostalgia.

The second trilogy is creatively flat, fun without being exhilarating or fully alive. The action sequences remain dense with excitement and visual poetry — the stories and the dialogue thud along as though no one cared much about them. The imagined worlds depicted are elaborate and inventive without being enchanting. The films work as entertainments on many levels, but they lack the spark of genius, of full-on creative commitment.

Someday, perhaps, kids who grew up on and enjoyed the films of the second trilogy will try to make movies that capture their youthful excitement about them, turning those B-movie dreams into something that transcends them. They will be doing what Lucas did when he made the first Star Wars trilogy.

THE BEST OF VIMEO

. . . highlights a Majestic Micro Movie by Jae Song.