Category Archives: Movies

THE SCOTTISH FILM

MARILYN REGINA

LLOYD’S MODERN LIFE: DOWN ESCALATOR

. . . featuring the saddest man in Las Vegas.

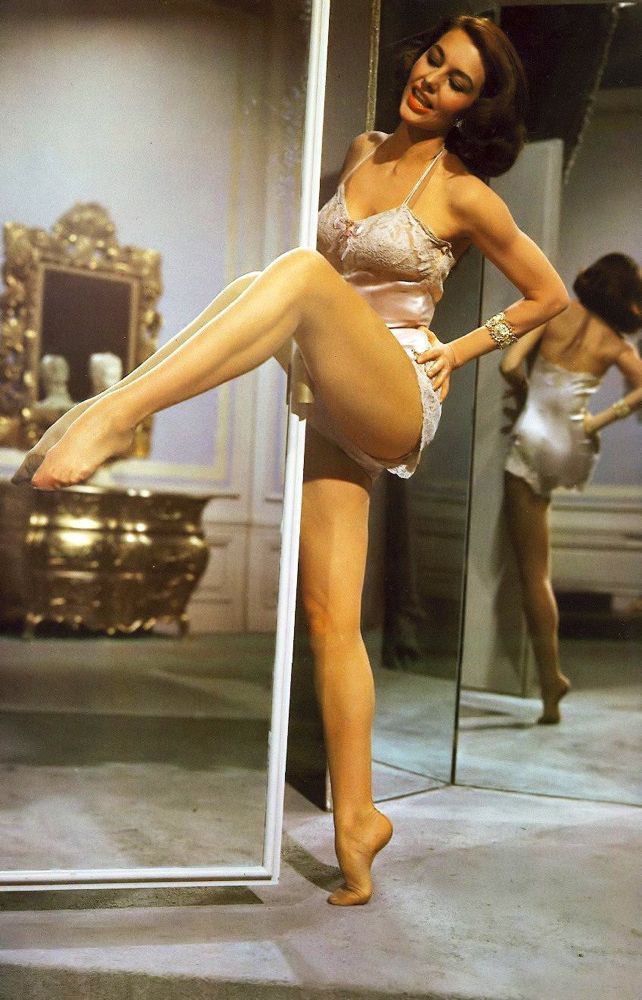

AND GOD CREATED WOMAN

TRY A LITTLE TENDERNESS

VIEW FROM THE REAR WINDOW

Fellow blogger Tristan Forward sent this amazing time-lapse conflation of all the shots in Rear Window taken from the protagonist’s rear window. It reminds us that Hitchcock didn’t just go to great lengths to make his protagonist’s apartment an interesting space to inhabit, cinematically — he went to equally great lengths to vary and enliven the POV shots looking out from that space.

BLU-RAY

Blu-ray is to DVD what vinyl is to CD — that is, it offers an incremental increase in quality that somehow takes the viewing or listening experience into a new realm. Vinyl sounds more like live music than a CD can, Blu-ray looks more like a projected 35mm print than a DVD can.

The Blu-ray quality is more important for some films than for others — beautifully lit films with shots composed in depth, like The Searchers, take your breath away on Blu-Ray.

It makes a great difference with a film like Rear Window, much of which takes place in a single room. Hitchcock works hard, through lighting and composition, to make that room seem like an interesting place to be confined. It feels bigger and more inviting when seen in a Blu-Ray presentation, offering the compensations Hitchcock counted on for limiting his male star’s presence to one relatively small space.

LLOYD’S MODERN LIFE: 5:54 AM

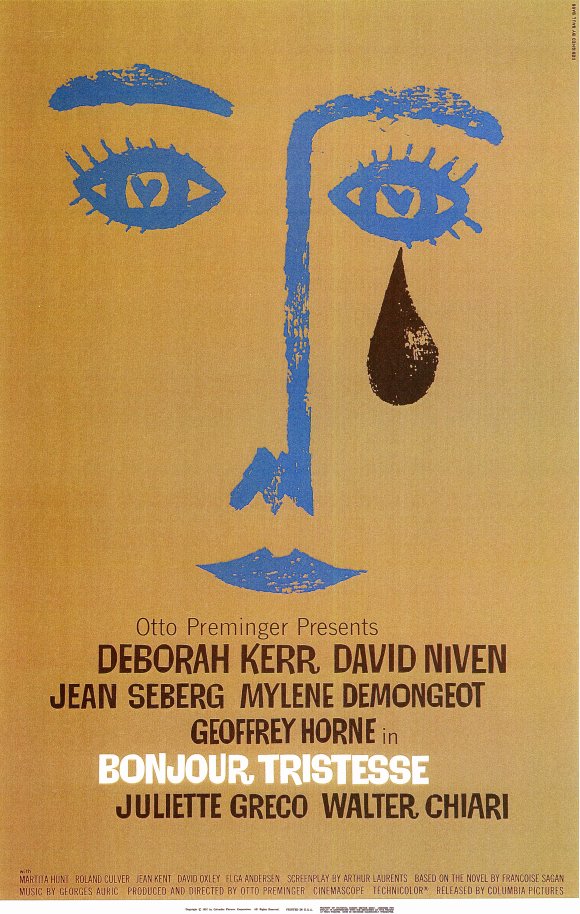

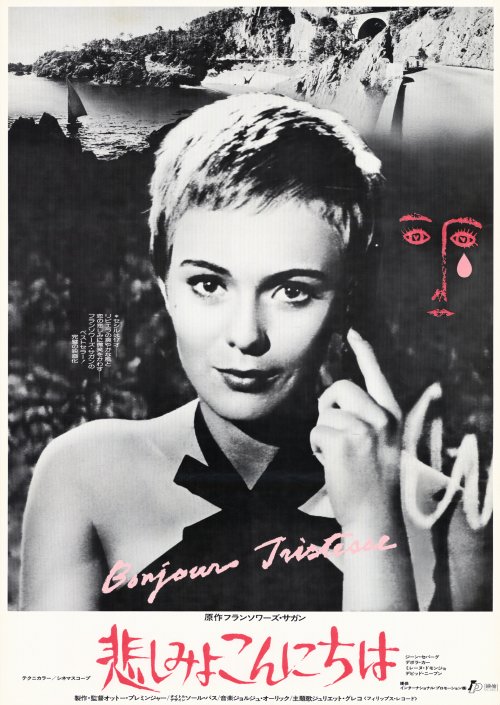

BONJOUR TRISTESSE

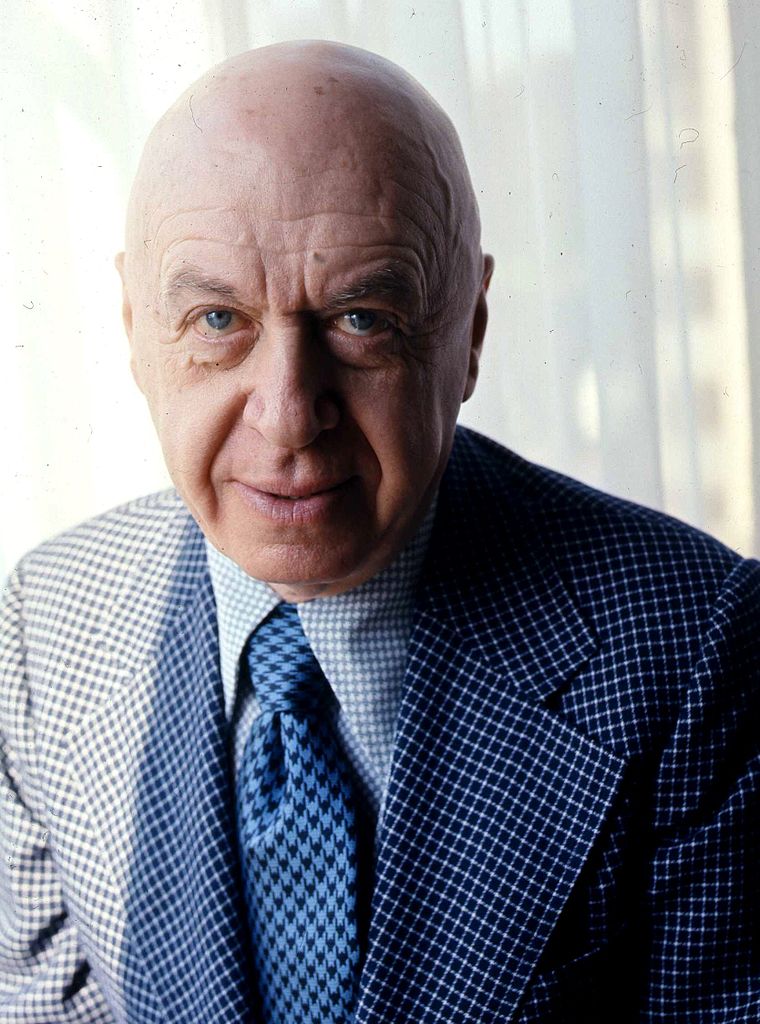

Otto Preminger’s body of work is wildly uneven but at his best he was a master of cinematic style — something the critics and directors of the French New Wave celebrated tirelessly but which has been largely forgotten in our time.

Preminger had an instinctive gift for creating arresting cinematic spaces, exploring them with a moving camera and choreographing movement through them. His method with these things was showier than John Ford’s, subtler than Orson Welles’s, but can stand comparison with the craft of either of those more revered directors.

Like Ford, Preminger was a martinet on the set but, unlike Ford’s, his abusive ways didn’t always motivate his actors to give great performances. Still, when he cast a film well, he presided over some memorable ones, and Jean Seberg’s performance in Bonjour Tristesse is one of the most memorable of them all.

Preminger had plucked her from obscurity for the title role in his film Saint Joan, in which she was brilliant but for which she received scathing reviews. Casting her as the lead in Bonjour Tristesse was a kind of reparation by Preminger for this unaccountable public humiliation.

As in the earlier film, Seberg doesn’t exactly act — she just has her being in front of the camera and becomes fascinating, in a way many better trained actors never manage. Her delivery is sometimes flat, her line readings clumsy, but she seems to project her whole self onto the screen, and you can’t take your eyes off of her, even when she’s interacting with David Niven and Deborah Kerr, who both give brilliant but more traditionally crafted performances in the film.

It was part of Preminger’s genius to know that Seberg’s kind of performance can make for riveting cinema, even if it’s not what mainstream audiences are used to and expect. Godard, among others, however, knew what Preminger was up to, and carried it forward when he cast Seberg in his first film, Breathless, which he described as a documentary about Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo making a movie. Their quirky onscreen personae never quite merge into the parts they are playing, and the tension of this is what makes Godard’s film so alive.

Seberg is the living heart of Bonjour Tristesse in the same way. Along with Preminger’s elegant shot-making, she transforms what might have been an overly precious coming-of-age melodrama into a cinematic marvel — working herself up to passages of emotional self-revelation that startle and devastate, climaxing in a final close-up that is surely one of the most powerful in screen history. Not that many people outside the offices of Cahiers du Cinéma appreciated her stealth genius at the time — the film tanked and Seberg again got dreadful reviews, which almost ended her career.

Twilight Time has just released a stunning Blu-ray edition of the film, and it’s a case where the higher resolution of the image reveals Preminger’s art more fully than the DVD edition, opening up spaces that you seem to fall into dreamily and in which Seberg’s magical screen presence blossoms and astonishes.

[The Twilight Time package contains, as usual, a superb booklet essay on the film by Julie Kirgo and an isolated track of the elegant and evocative score by Georges Auric. Actually, the score shares the track with the effects track, mostly heard between the music cues but sometimes underneath them. The effects track is extensive, very built up, suggesting that Preminger used very little location sound in the final film and looped most or all of the dialogue. It would be interesting to know if that was part of the production plan, allowing Preminger more freedom to move his camera on the practical locations where virtually all of the film was shot, or if it was something he decided to do after the fact in order to give him more opportunity to work with Seberg on her line readings.]

Click on the images to enlarge.

ON THE SET

AND GOD CREATED BARBARA STANWYCK

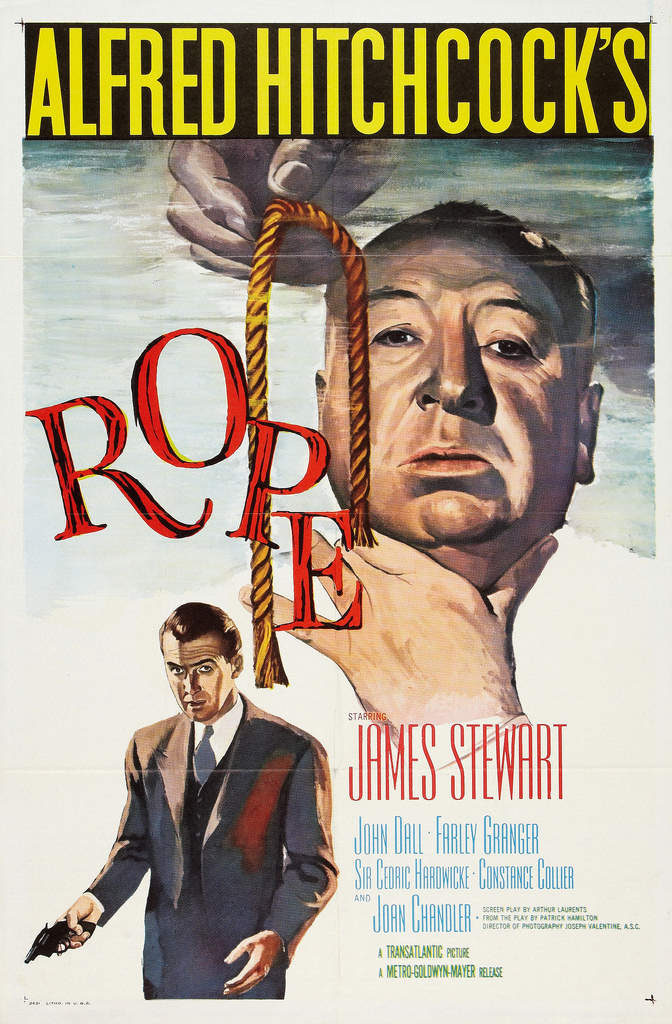

ROPE

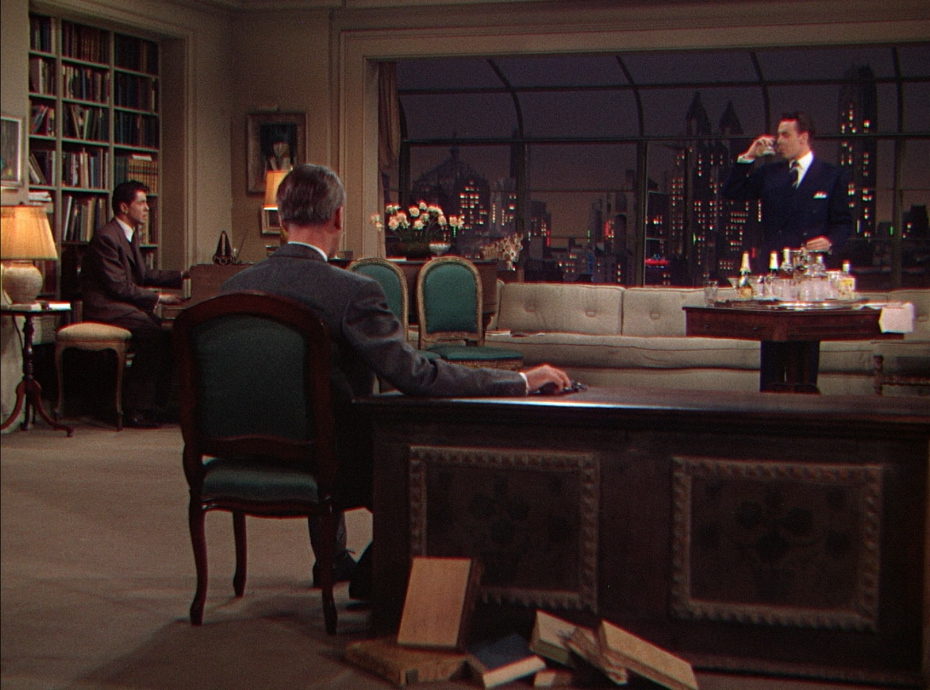

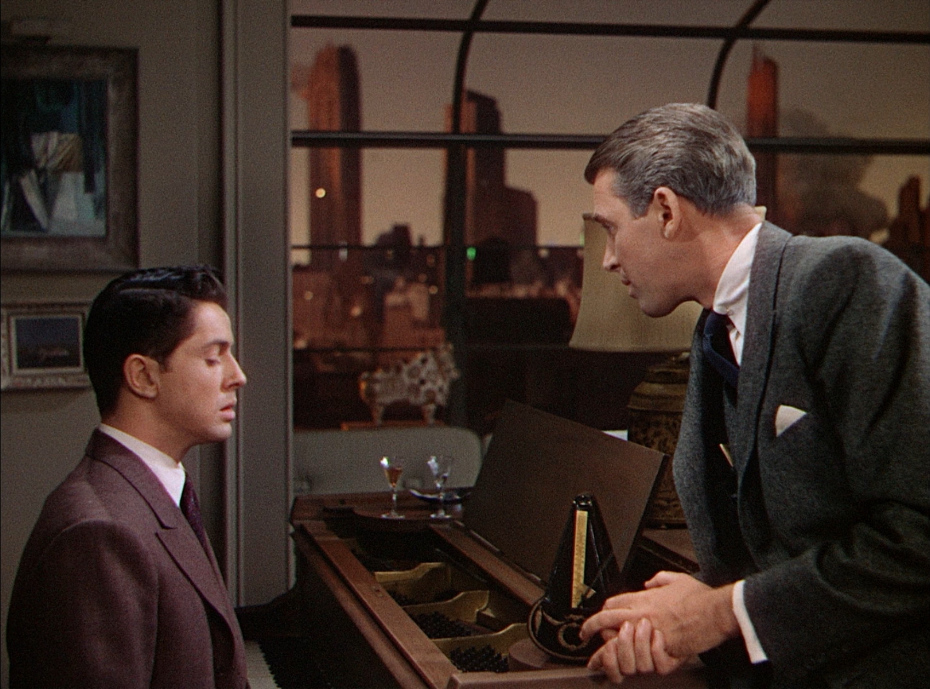

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope is a film that really opens up and comes alive in the new Blu-ray edition. (It does so even more with a good print on a big screen, if you’re ever lucky enough to see it that way.)

Rope is at its most basic level a movie about a set, a magical set with walls that can be moved off screen during shooting to accommodate elaborate camera moves through its spaces, which consist of four rooms in line — a living room, a foyer, a dining room and a kitchen. The camera moves in and around all these rooms except the kitchen, which is only seem through its door.

The film is shot in a series of ten ten-minute takes — the maximum shot length possible for a film camera of the time. The camera moves almost constantly to re-frame elements of the shots for dramatic purposes, since Hitchcock chose not to use editing for this purpose. The cuts between the shots are disguised in various ways to give the impression of the film unfolding as one continuous shot.

There is canny calculation in all this. The elegant movement of the camera through apparently constrained spaces seems magical at first — and the better the print the more magical it seems. But gradually we come to realize the limits of the spaces, to realize that the camera is never going to to move outside them, and this creates a a creeping sense of claustrophobia.

This formal strategy mirrors the emotional claustrophobia of the drama, which centers on a domestic partnership between two gay men which is coming apart at the seams under the pressure of a neurotic power imbalance in the relationship.

The homosexual subtext is never made explicit, but we can feel it in every interaction between the two partners, and we gradually come to understand that this is going to be the primary romantic dynamic of the film — that all the other romance alluded to in the story will stay permanently off-screen.

This would have been a shocking thing to mainstream audiences of 1948 and would have induced another kind of claustrophobia, a thematic claustrophobia, beyond the claustrophobia induced by centering a movie around a romantic relationship that is unraveling before our eyes and has nowhere to go but into catastrophe.

The film seems radical even today, for its technique and its thematic daring. By never mentioning its homosexual subtext, not possible in any case in Hollywood in 1948, it also avoids any kind of special plea for understanding, and thus any kind of patronizing of its gay characters. They are not terribly admirable men, but they are sympathetic on many levels and, more importantly, they are simply who they are — without apology or comment.

Rope is not exactly a pleasurable piece of entertainment — it’s disturbing in many different ways — but it’s a dazzling exercise in cinematic eloquence and dramatic finesse.

Click on the images to enlarge.

ADDENDUM

Facebook friend Catherine Grant reminds me, through this very useful video essay, that not all the cuts in Rope are disguised:

Indeed, the first cut is very much undisguised and meant to startle. I would still say that, except for that first one, the undisguised cuts are all designed to be as unobtrusive as possible, to create the sensation if not the seamless illusion that the film unfolds as one continuous shot.

WHAT I’M SPINNING NOW