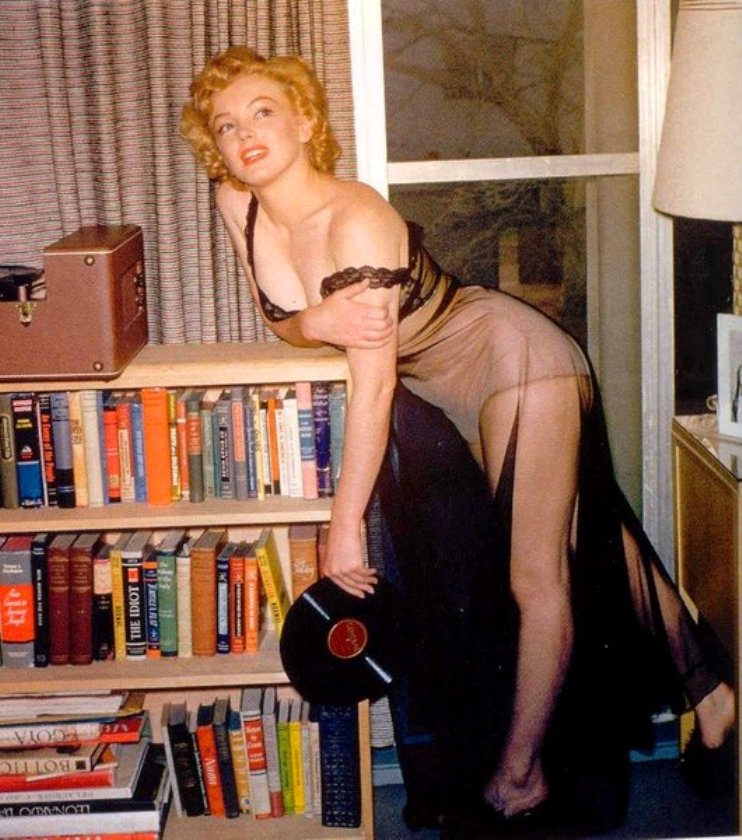

There are few films as entertaining and as beautiful to look at as the series Josef von Sternberg made with Marlene Dietrich in Hollywood in the 1930s. It would be wrong to see them — or, God forbid, dismiss them — as exercises in camp. They are not ironic send-ups of the exotic romance film — they are in fact attempts to take the exotic romance film as far into the realm of delirious sensuality as it can be taken. They treat romance and Eros absolutely seriously, as long as we admit that play and perversity are serious elements of romance and Eros.

At heart they are sweet films — films about people disillusioned with true love who somehow find a way to believe in it again. On the surface, however, they seethe with pure carnality, unfolding in a thoroughly eroticized universe, and it’s Dietrich’s persona and Von Sternberg’s visuals which do the eroticizing. Dietrich usually starts out world-weary and skeptical of men, but the pose never becomes totally cynical. Her characters hold onto the fun of sex if nothing else, and the loving, elegant way Dietrich is lit and photographed suggests that there’s a deep and transcendent nobility in her characters’ wry good humor about it all.

The narratives of the films, often quite preposterous, are mere pretexts for a celebration of female sexuality — the mad images of an utterly artificial world are no more than window dressing for the mad game of sex, but the mad game of sex is always ultimately about love.

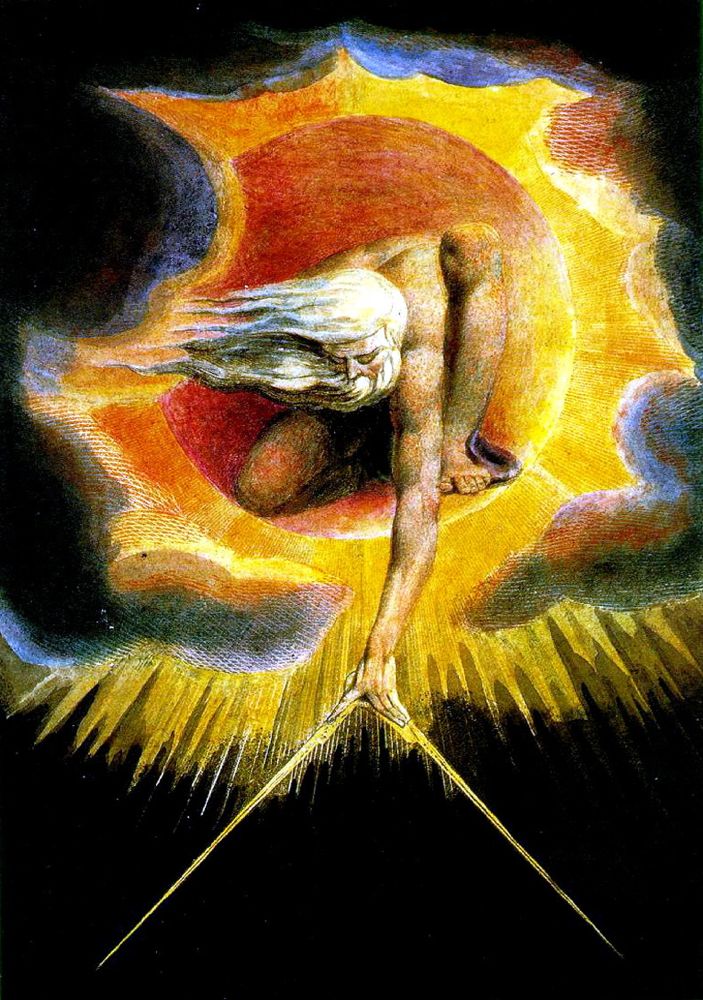

William Blake wrote:

There is a smile of love,

And there is a smile of deceit,

And there is a smile of smiles

In which these two smiles meet.

This is Dietrich’s smile in these films — bewitching, beautiful, mysterious and profound.

Click on the images to enlarge.