The greatest, or possibly the dumbest, road movie ever made . . .

The greatest, or possibly the dumbest, road movie ever made . . .

This is not one of the great Hollywood epics but, boy, is it fun. If you watch it on a decent-sized TV in the Blu-ray edition by Twilight Time, the lunatic spectacle of it all will carry you comfortably through its general silliness. You can bask in the technical virtuosity of the 20th-Century Fox studio at its zenith, marvel at director Michael Curtiz’s elegant professionalism, and gaze in awe at what stars could do with less than stellar material . . . and at how non-stars, like the ill-chosen leading man Edmund Purdom, could be given a kind of imputed charisma by their surroundings. The whole thing is just a hoot from start to finish.

Elsewhere on this site Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) has written a more sympathetic evaluation of the film — Walking In Memphis — with some fascinating observations on Jack Kerouac, who saw it when it first came out and hated it!

[Let me take this opportunity to apologize for the erratic formatting of many old posts here — the unavoidable by-product of a switch to a new blogging platform. I am trying to regularize the formatting of these old posts to the degree that it’s possible, but it will take me some time to get around to all of them.]

Kendra Elliott and the three Js take a superficial look at deep focus . . .

Terrific 5-minite film by my nephew Harry Rossi and his cohorts in the NCSA filmmaking program . . .

A Majestic Micro Movie directed by Jae Song.

You’re probably thinking, “No, not for me” — but The Saturni urge you to think again . . .

The secret of film directing . . .

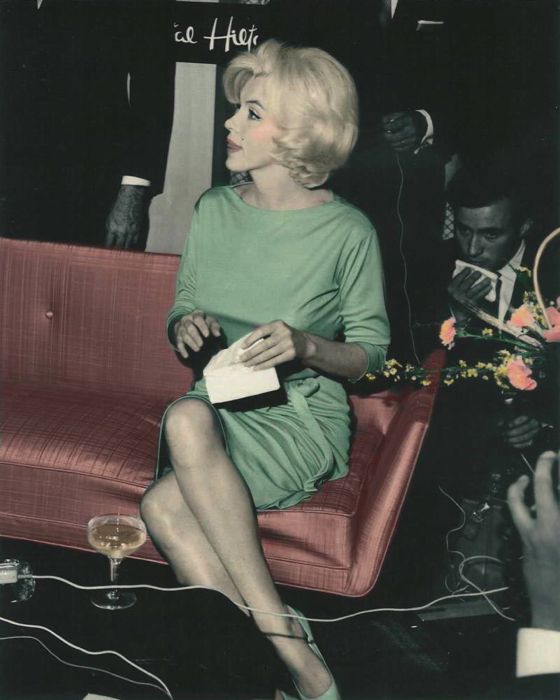

Marilyn Monroe was buried in this Pucci dress which she had worn at a press conference in Mexico City (above) six months before she died. It was chosen by her half-sister and two of her assistants. Her personal make-up man came in to prepare the body for burial, as he had promised he would. It was a difficult task, due to the damage done by the autopsy. Monroe's breasts had been mostly done away with, for example, so the dress had to be stuffed to restore a semblance of the legendary bust, and the corpse was also fitted with a wig, one Monroe had worn in her last uncompleted film, to cover incisions made in the skull.

Dust to dust — even for the most beautiful among us.

Marilyn Monroe, on why she was sometimes difficult on the set, wanting her performance to be perfect:

I used to go to movies on Saturday night when, for instance, when I worked in a factory, and that was my only time that I could enjoy myself, really, that I really relaxed and enjoyed myself, and so, I used to be really disappointed if I went to a movie — 'cause I waited all week to go to the movie, and I worked hard for the money I spent — and if I went to a movie and it was a bad movie and I thought people didn't do their best, kind of did it sloppy or something, I really was mad, you know, angry when I left, 'cause then I didn't have anything to go on for a whole week. I'd wait for another week.

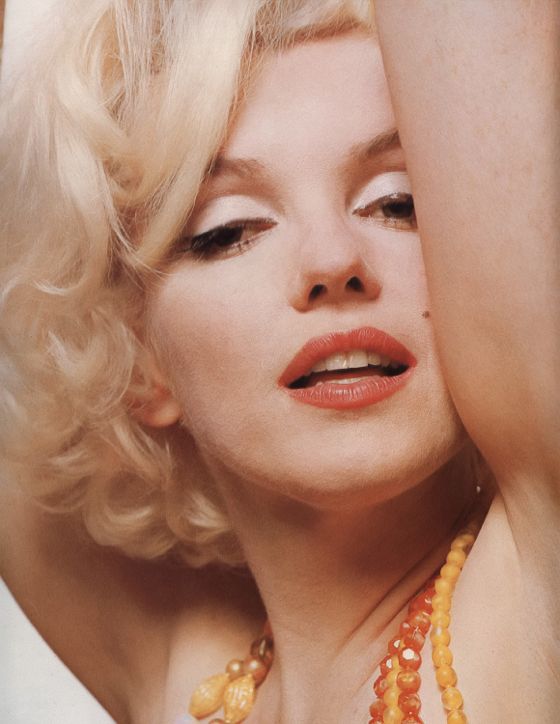

In many of her films, Marilyn Monroe played “Marilyn Monroe”, a relatively fixed persona, the one that made her a star and an enduring icon. “Marilyn Monroe” was a slightly ditzy, intuitively wise blond bombshell. She spoke in a little-girl voice and paraded her sexuality with a cheerful, almost infantile innocence. But there was a lot more to it than that.

Monroe the actor presented this persona with an elegance and precision that required artfulness of a very high order. Her control over her voice was considerable, her control over her body sublime. You can see this most clearly in her musical numbers. She did not have a naturally strong vocal instrument, which makes her witty and/or dramatic readings of songs that much more impressive. She was not trained as a dancer, which makes her dance moves, always so lyrical and finely executed, that much more surprising.

This physical control over her body is present in all her screen appearances, even in purely dramatic roles. She knew how to possess space as only the greatest screen actors can. She is one of the few sound-era movie stars who could have been just as stellar in the silent era. Her style of movement involved extreme virtuosity. But there was a lot more to it even than that.

Monroe's virtuosity as a performer was so well calculated and well executed that it introduced an element of irony into her style, contradicting the ditzy side of the “Marilyn Monroe” persona, emphasizing the intuitively wise side. This could be disturbing, anti-erotic, even, suggesting that the real joke in all her comedies might be on anyone who took that persona too seriously. She created or perfected a powerful erotic style while at the same time critiquing it — but there was never a hint of condescension or parody, of camp, in the critique. Compared to Mae West, or Madonna, or Lady Gaga, performers who have worked the same vein of erotic irony, with a leering wink or a hip sneer, Monroe had the touch of a lyric poet.

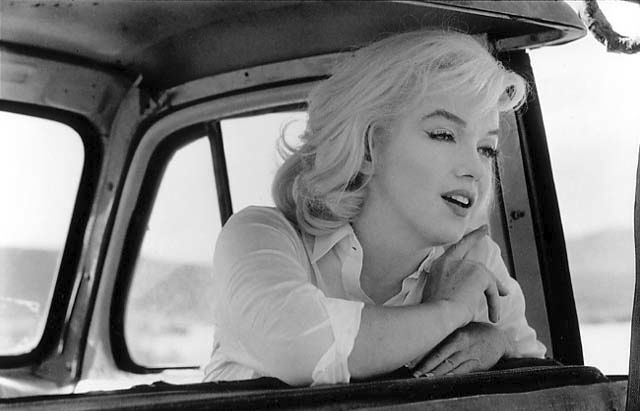

Most miraculous of all, Monroe was able to translate this persona into her non-musical, non-comedic roles. “Marilyn Monroe” was the creation of the actor, her writers and directors, and her public — but it wasn't mere artifice. There was a psychological truth at the heart of the persona. Many real women present themselves as childlike but sexual, exhibitionist but innocent, scatterbrained but deeply knowing. The strategy reflects both an inner insecurity and a canny appreciation of male insecurity. In her straight dramatic roles, Monroe was able to translate this insight into more naturalistic terms, fold it into characters whose strategies of self-presentation are perfectly recognizable as those of people we have all met in ordinary life.

The insight, in whatever form it's manifested, results in a resonant paradox. The ability to manipulate men, to fashion a mask that will attract and console them, is a form of female power. But it is also a source of female despair — what woman wants a man so easily manipulated? What woman doesn't want to tear off the mask and be seen for who she is — even, and perhaps especially, if she herself doesn't know who she is? Sexual love is undoubtedly a game, but it's a game that promises to reveal the deepest truths about those who play it.

The ultimate question Monroe the artist asks is — how can the game be played if one of the players doesn't know it's a game or, if he does know, doesn't know how to play it very well? In the era of collapsed manhood that followed WWII, asking that question made Monroe an international sensation, an icon, a crucial cultural figure. She remains sensational, and essential to American culture, because the question still haunts us, still has no answer.

Some might argue that the “Marilyn Monroe” persona was one born of limited range and skill, but this is like denigrating a great shortstop because his athletic prowess doesn't mirror the athletic prowess of a great boxer. They're playing different sports, in different arenas. If you prefer one to the other, make sure you've got tickets to the right event — and if you find yourself at the wrong event, don't blame the athletes who are playing a game you don't enjoy or appreciate.

[Photo by Mary Zahl]

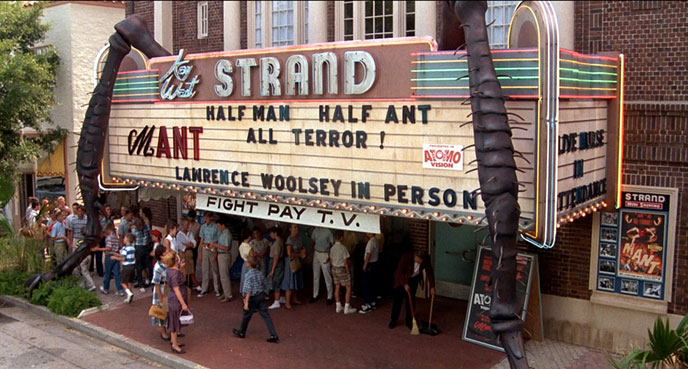

Above, Paul Zahl in front of the Cocoa Beach Playhouse in Cocoa Beach, Florida. Paul's visit to the theater, not too far from where he lives, in the Orlando area, was in the nature of a pilgrimage, since the Cocoa Beach Playhouse figured prominently in one of his favorite movies, Matinee by Joe Dante, where it doubled as the Strand theater in Key West:

There was a real Strand theater in Key West (now closed and turned into a Walgreen's) but for logistical reasons it was decided to dress the Cocoa Beach theater to represent it when Matinee was shot in 1993.

Matinee is a really enjoyable movie — check it out if you haven't seen it. Hard to find for many years, it was re-released on DVD in 2010.

When she died in 1990, Barbara Stanwyck was cremated and her ashes were spread, at her request, in Lone Pine, California, reportedly because she had enjoyed making Westerns there.

The Violent Men (above) is the only Stanwyck Western I can track down that was shot in Lone Pine — there may have been others.

Lone Pine is haunted by many movie ghosts, because a lot of movies have been made in the beautiful country around it. I felt their presence when I visited the place for the first time two years ago, but I didn't know then that Stanwyck was literally there, in the dust among the rocks, in the wind. I need to go back now, and take some flowers.

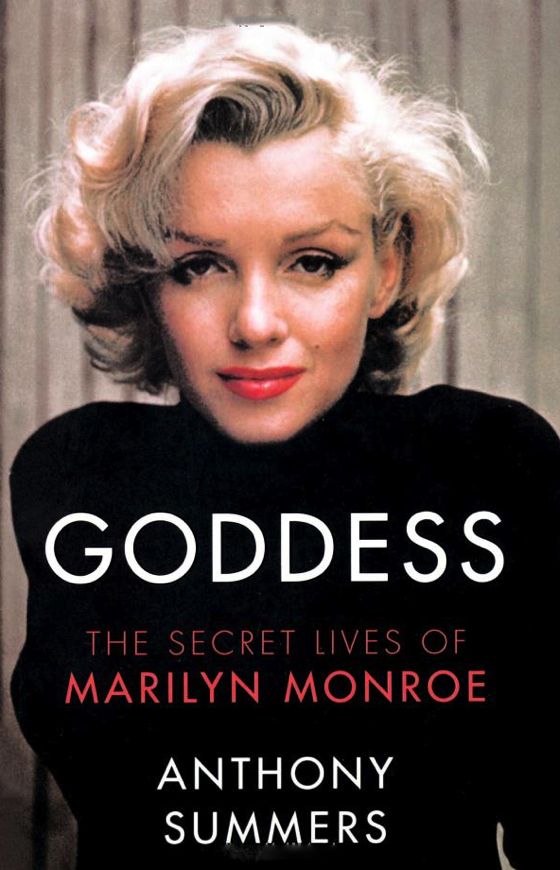

Goddess is a long and detailed biography of the amazing Marilyn Monroe. Summers, like most biographers of the star, is after dirt and scandal, but he seems to have been fairly scrupulous about reporting only the scandal and dirt he could corroborate through meticulous research, juiced up here and there by speculations that are reasonable or not totally unreasonable, depending on your point of view. Written originally in the 1980s, Summers's book reported an affair between Monroe and Elia Kazan, based on the testimony of acquaintances Summers found convincing. Kazan's biography, published a few years later, confirmed the truth of Summers's account. One has a sense that he mostly got things right.

Fully one third of the book, however, is devoted to his investigation into the last two years of Monroe's life, her rumored affairs with John and Robert Kennedy and the mob's interest in those affairs for possible use as blackmail. This was the “new” and most sensational material in the book when it came out, but not all readers will have the patience to follow every twist and turn of the obsessive research Summers did on the subject. Those who do will not find much to admire in the Kennedy brothers as men — they were slimeballs of the lowest sort in their private lives.

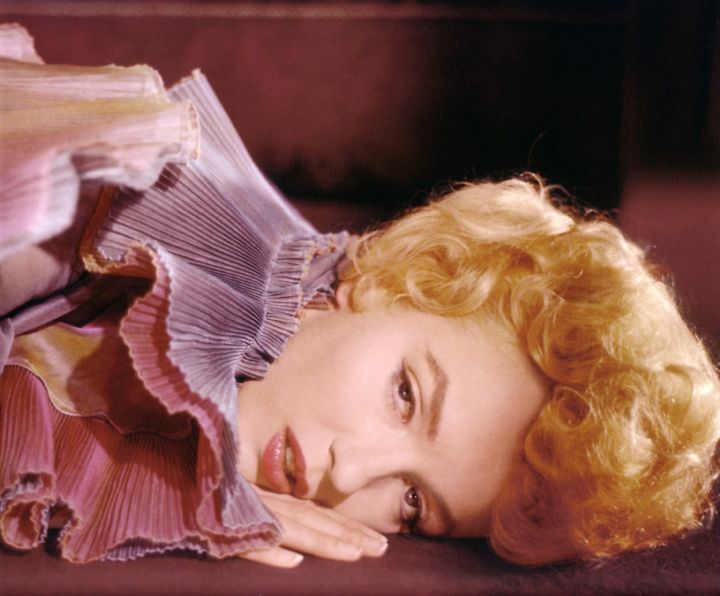

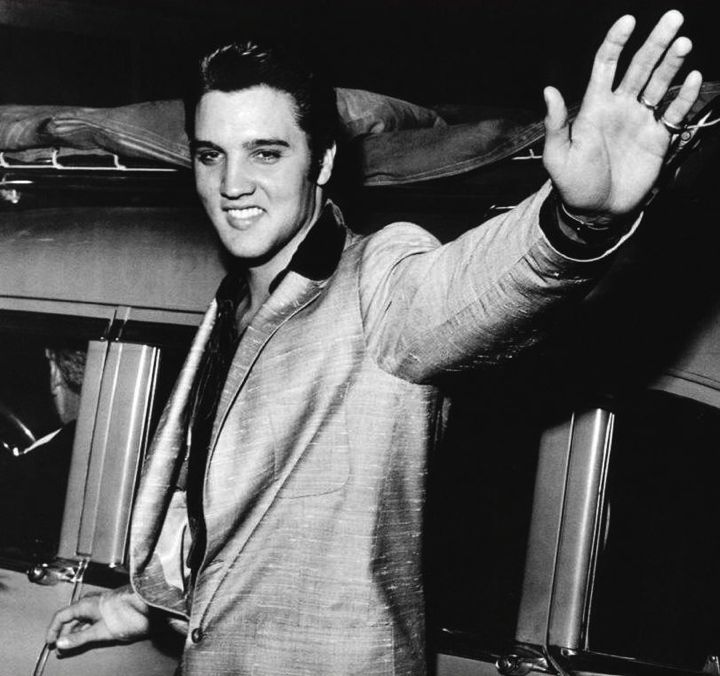

What emerges in the end is the tale of a stupendously and increasingly sad life, ending in a drug-induced haze, profound loneliness and overwhelming depression. It is very much like the tale Peter Guralnick tells in his much finer biography of Elvis Presley — the tale of a canny, ambitious, brilliant but shockingly innocent artist fulfilled at first and then crushed by success and fame.

As with Elvis, the redemption is to be found only in the work, whose magic endures long after the personal nightmare came to its end in the grave. It's a magic that was perhaps delightful to Monroe while she was making it but added up to less than nothing for her at the sorry end of her days. There's no particular moral to these tales. Both Elvis and Marilyn were damaged people, helpless to resist the addictions that killed them — addictions that irresponsible doctors and friends were only too happy to enable, in return for proximity to the intoxicating glamor of a star.

All we can do is turn back to the work they did, still bright and enchanting, still full of joy and life, and say a prayer for the repose of their souls.