Here, Paul Zahl takes a look at an undervalued film by Jacques Demy, and finds much value in it, indeed:

HIS ODD BEAUTY

people seem able to say no to Jacques Demy's vision of life as reflected

in wonderful movies such as

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and Lola (1960). A phrase that seems to cover his vision is “optimistic romanticism”. Those are two good words for it.Demy

made several more films, however, and three of them,

A SlightlyPregnant Man (1973), Lady Oscar (1979), and Parking (1985) are

considered bombs. I've seen them all recently, though only segments of Parking, and can well understand their bad reputations.

But I disagree about Lady Oscar!

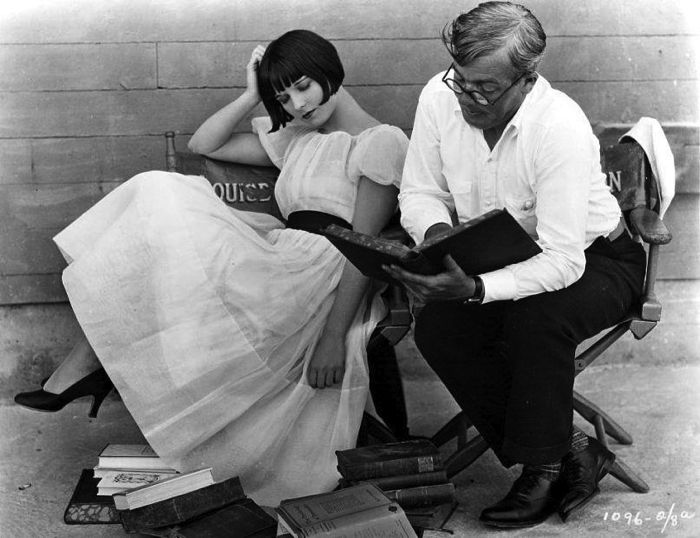

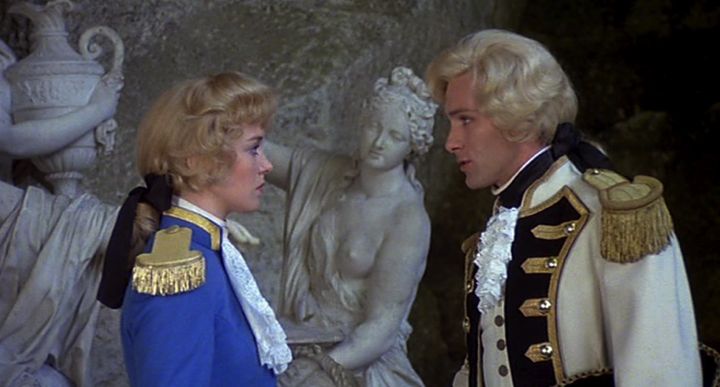

Lady Oscar is a beautiful movie, an opulent, visionary movie, about a

cross-dressing aristocratic heroine, played by Catriona MacColl, in the

Court of Marie Antoinette, who sees and hears the great events of the 1780s in her role of Captain of the Guards, while all the while loving the faithful, kind, courageous stable boy 'André Grandier', played by Barry Stokes.

The movie was directed and also partly written by Jacques Demy; and its lush, sentimental musical score is by Michel Legrand. Most of the actors were English but the film was filmed in France,

much of it at Versailles. An alternate title for the movie was The

Rose of Versailles.

The big stunner, when you

sit down and watch Lady Oscar, is the opening credit revealing that it

was Toho Studios of Japan that produced the film. At first glance, because of that familiar logo, you expect Mothra to come flying into the film. But

no, or rather, “Non!”: it's the fashionable, swirling, and almost

feminine style of the man who directed Catherine Deneuve, Françoise

Dorléac, Anouk Aimée, and later, Dominique Sanda.

In other words, this is a mélange, an improbable

mix of commercial and historical elements, which, taken together,

produced an odd movie — at least, if you stop to consider the

ingredients. Turns out Demy was not getting much work at the time; that the

Japanese had a popular commercial property on their hands, which was a

comic book entitled The Rose of Versailles; and that Lady

Oscar was made entirely and by design for domestic consumption in

Japan, even though it was filmed in France, with English actors, English

dialogue, and a French crew. Lady Oscar's being owned by Toho of

Japan is the main reason it hasn't been seen very often in Europe and

America — until now, that is, with the release in 2008 of a “Jacques

Demy Integrale” boxed set in France.

Long story, isn't it? Has all the makings of a colossal flop, right? Too many cooks spoil the broth, “n'est-ce pas”? You might think so. And many do. But I think Lady Oscar is a touching, lovely, sexy, beautiful movie.

Click here to continue reading and find out why: