My nephew Harry and my friend PZ discussing movies — the subject here, Kurosawa!

My nephew Harry and my friend PZ discussing movies — the subject here, Kurosawa!

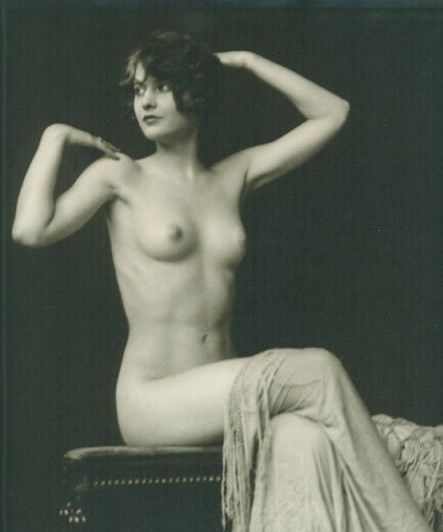

The former Miss Ruby Stevens, in excelsis . . .

Just as the industrial labor process separates off from handicraft, so the form of communication corresponding to this process — information — separates off from the form of communication corresponding to the artisanal process of labor, which is storytelling. This connection must be kept in mind if one is to form an idea of the explosive force contained within information. This force is liberated in sensation. With the sensation, whatever resembles wisdom, oral tradition or the epic side of truth is razed the ground.

— Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

Storytelling is linked to artisanal labor because it is created out of the life experience of an individual storyteller, most especially the time spent learning the craft of it. It's not so different from making furniture by hand. Information, by contrast, is merely collected and repackaged. It has the nature of an industrial product, which can be separated from the process of its creation and sold like any other commodity.

Storytelling embodies, at its best, as Benjamin notes, wisdom, tradition and a truth that transcends both the moment and the immediate context of its telling — it is epic in that sense. Information has commercial value to the degree that it embodies sensation — sensation in the sense of surprise or shock value, and sensation in the sense of newness or exclusivity.

Most modern movies don't tell stories — they sell sensation.

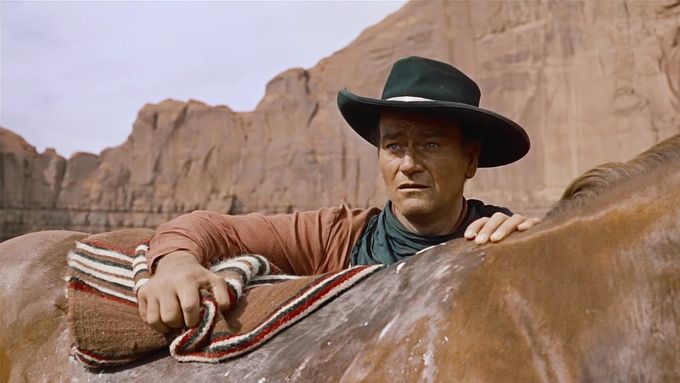

Facebook friend Ray Sawhill has a theory that classic Westerns deal with the themes of shame and honor, which began to feel old-hat in the Sixties when movies shifted more and more to the paradigm of guilt and therapy, following trends in the culture at large.

This wasn’t a universal trend, however — even though it came

to dominate Hollywood (which still has a strong culture of guilt and

therapy) as well as various other self-styled cultural elites — because

whenever a Western dealing with the themes of shame and honor has

managed to slip past the Hollywood gatekeepers, it has invariably found

a big audience. See Unforgiven and the new True Grit, for example.

As I see it, the difference between shame and guilt in this context would be — shame is something you feel because of your own failings, while guilt can be seen as something imposed on you unfairly by others. The difference between honor and therapy would be — honor requires you to make moral choices and take moral actions, while therapy can be seen as something you pay for with cash and consume passively, without the intervention of moral thought.

Therapy strives for vindication and healing — honor strives for redemption, and redemption is the theme of almost every great Western.

You have to have unusual power and authority in Hollywood to get a shame-and-honor Western made, you have to be Clint Eastwood or the Coen brothers, because the industry simply doesn’t understand such movies, and to the degree that it does understand them, it hates them, even when they make a lot of money — perhaps especially when they make a lot of money. If there ever is a full-scale revival of the traditional Western, it will have to originate outside of Hollywood.

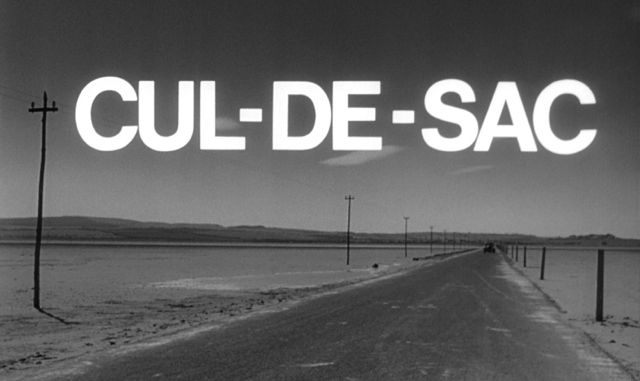

Roman Polanski's 1966 film Cul-de-sac is a slight work — its absurdist nihilism and casual misogyny add up to a fairly puerile vision of the human condition — but it's a wonderfully made film and consistently entertaining. There are hilariously eccentric performances by Lionel Stander and Donald Pleasence and by a fine supporting cast, and the film is beautifully shot in a truly strange location that itself becomes a major character in the tale.

The presence of Françoise Dorléac contributes an unintended poignancy to Cul-de-sac — she would die in an automobile accident a year after the film was released. She doesn't have much of a part — playing the fickle and vapid wife of Pleasence. She takes her clothes off on a regular basis, to remind us that she's the decisive female presence over whom and before whom Stander and Pleasence enact their preposterous duel of wills, but she doesn't seem to have much will of her own. She doesn't help drive the story — she just complicates it and decorates it.

Still, she's so luminously beautiful and fascinating that Polanski can't quite reduce her to feminine inanity — one senses a woman in her who might have given the film real depth and power if Polanski had taken her character a bit more seriously.

Pleasence's character is apparently haunted by an earlier relationship with an unseen “Agnes”, referenced glancingly here and there but whose name becomes a cry of anguish at the end, a summary of something lost long before the film began. But it's Dorléac's name one wants to speak at the end now — dead at the age of 25, leaving only a modest body of work behind her, some of it quite wonderful. What she might have accomplished in this film, had Polanski's not kept such a pyschic distance from her, becomes a symbol of all the work she might have done had she lived.

Jean Vigo's first film, the “documentary” À Propos de Nice, from 1930, can certainly be read as a social commentary — indeed, Vigo himself urged viewers to read it as a social commentary. In the French left-wing circles Vigo moved in, documentaries which offered a critique of bourgeois life or a celebration of the proletariat we're more or less de rigeur.

In fact, however, Vigo was hardly a doctrinaire leftist — he was an anarchist, who never joined the Communist party, and would have naturally opposed any system of reform whose results could be anticipated in detail. He believed that extreme freedom would create its own unforeseeable utopias.

More importantly, Vigo was primarily a visual poet. His portrait of Nice connects most directly with the works of his peers who were interested in creating documentary poems about cities, celebrating their energy in lyrical terms — another reason why À Propos de Nice resists a simple political analysis.

Yes, the film contains ironic and often unflattering images of the idle rich enjoying themselves in a bourgeois playground by the sea — but Vigo seems at least as amused and delighted by these images as appalled. They have the whimsical, endearing, even celebratory quality of Lartigue's photographs of the same class in the same sort of settings. And Vigo's images of the working-class people of Nice utterly lack the heroic quality considered appropriate by more didactic left-wing filmmakers.

Whatever he thought he was making, Vigo in fact created a unique film that celebrates life, energy, movement. It is a reflection of the joy he took in the world as it was — made poignant by his frail health, and perhaps his own sense that he wouldn't have long to enjoy that world. The film ends with images of mortality — statues in a graveyard, carnival figures consumed by flames. As it was, Vigo died at the age of 29, four years after this film was made.

Vigo said that he thought a documentary should reflect not some objective truth about things but a “documented point of view” about things. Ultimately, the documented point of view reflected by À Propos de Nice is simply joy, made sweeter by a sense of the ephemeral nature of joy. The leftist pieties on its surface dissolve into the spirit of the filmmaker — a cheerful, antic, sensual soul, amazed by the world and by what cinema could make of it.

Kendra Elliott's first live-action short, Beatrice and Bob, will have its East Coast premiere at the Woodstock Film Festival on 23 September, with another showing on 24 September:

Screening Times and Tickets

Kendra is a brilliant artist and animator, and a wonderful actor who really helped make Jae Song's Majestic Micro Movie Essays On Cinema special. It will be interesting to see what she does in her first foray into live-action directing.

If you're in the area — check it out!

This film is a “mystical” love story — its script is a farrago of flapdoodle and mythological symbolism. It simply can't be taken seriously. And yet, and yet . . .

Its images, created by the great Jack Cardiff, are so lush and beautiful, so seductive, and its story has such oneiric momentum, that one is captivated in spite of oneself. Martin Scorsese has said that watching it is like being drawn in to a strange and wonderful dream, and the stranger it gets, the more convincing it becomes, as often happens with dreams.

It is a movie one inhabits, even if one's sense of good taste and reason urge one to resist it. I can't say that it produces the emotional effects it seems to be trying for, but it's a lovely, delirious vision, and it stays with you long after its narrative evaporates in your mind.

Perhaps it's Ava Gardner who engineers the miracle — unconvincing as a symbolic reincarnation of the mythological Pandora, she is utterly convincing as a mythological creature in her own right, self-contained, potent, invincibly female.

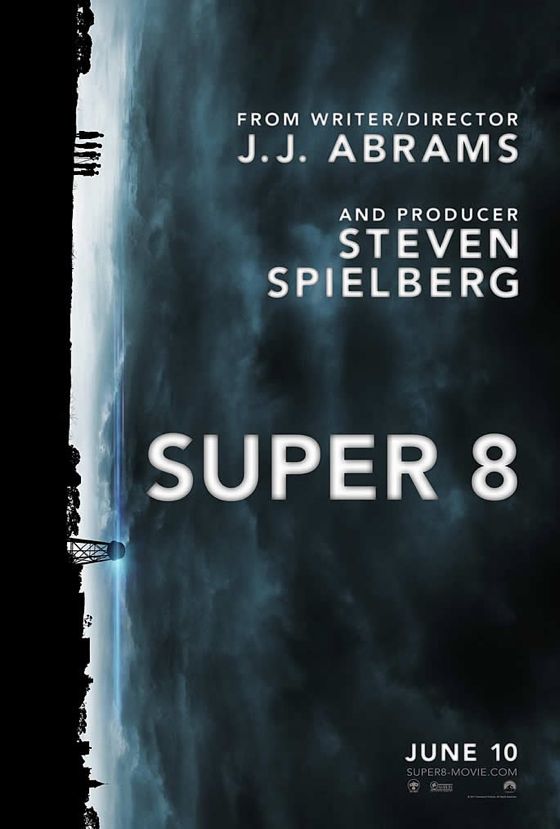

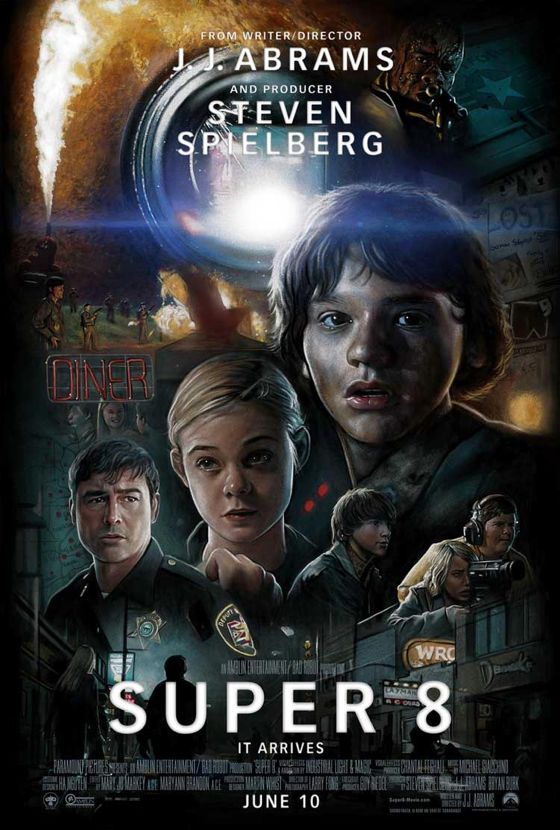

A few viewings of the movie Super 8 prompt some musings from Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) on the layers of life and on the difficulty of telling a facade from a foundation:

BACK TO FRONT IN SUPER 8

There are two stories within the movie Super 8. Which is the “front story” and which is the “back”?

There are two different realities depicted in Super 8. Which is true and which is false? Or rather, which is really real?

The two stories of Super 8 are the story of childhood, on the one hand, and of adulthood, on the other.

Joe is grieving the death of his mother, Charles wants urgently, to the exclusion of all else, to finish his movie, Cary loves to blow things up and burn things down, and Alice wants to be able to love her father. The children see nothing else, hear nothing else, and can talk of nothing else. The children are immediate with their feelings: there is no monitor governing their emotions. Moreover, the children find out, long before anyone else does, what's really going on.

The adults, on the other hand, are trying to control everything. The USAF is trying to control the world. Joe's Dad is “scrambling” — the current word — to control the panic of the town. The merchants of Lillian, Ohio are calling their insurance companies; meeting fruitlessly and interminably to discuss the problem, and with all the wrong information; and blaming “bears” or the Soviets. No adult has the slightest idea what is going on, except the local science teacher, who understands it from the inside out.

The children, in other words, are right with the truth, from start to finish. Instinctively, because of their ungoverned feelings — not a bad thing in this movie — they are never wrong, about any aspect of their lives. I believe this is true in life. “A little child shall lead them.” “Unless you become as a little child, you shall in no wise enter the kingdom of heaven.”

The two stories in Super 8 reflect the two realities of Super 8. The children see everything as it is, or you could almost say, only as it is. The adults, so full of worry and fret, so completely engrossed by conflicting supposed obligations and responsibilities, see nothing as it is. The cost to the adults is the near destruction of their lives and town. The gift to them from the children is knowledge, understanding, and reconciliation.

Super 8 is also monistic. It is a monistic work of popular art. By this I mean that it portrays love and compassion — sounds like a cliché, doesn't it? — as universal to all creatures, including alien monsters. The playing field of love is level.

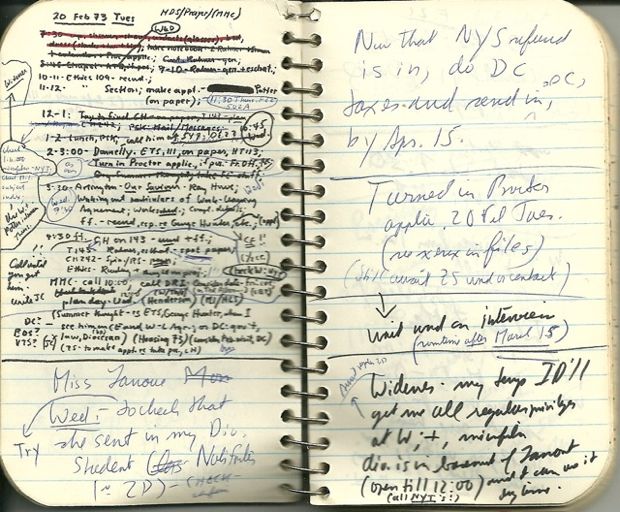

Recently I came across ten little notebooks, notebooks for a person's breast pocket, which I used for my to-do lists during the Winter and Spring of 1972-1973. I was a recent college graduate and quite confused, about absolutely everything. A lot was going on, and just barely underneath the surface. It mainly concerned girls, and sex; not to mention who did I wish to be and become. I was striking out on almost every front, though there were a few shafts of light oddly breaking through. But those notebooks, goddammit!

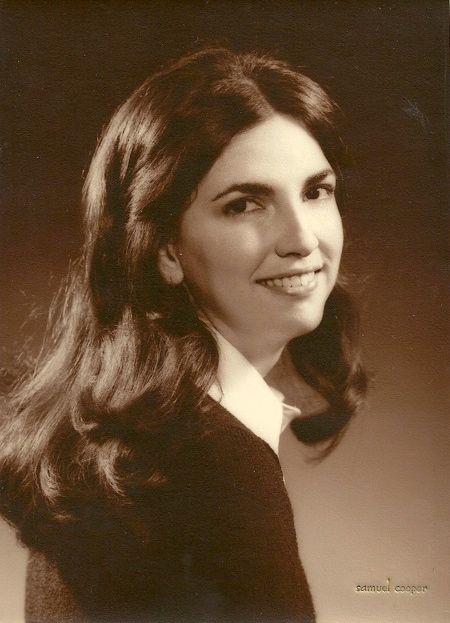

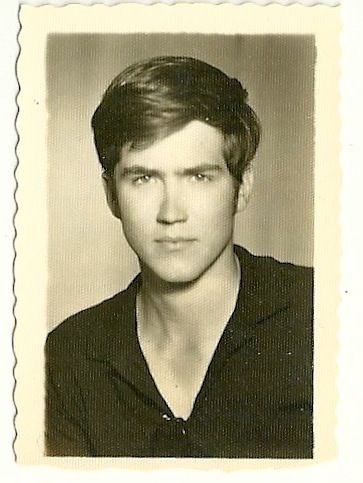

I read them again. They are lists and lists of “urgent” things to do: letters of recommendation to get, applications to complete, courses to take, contacts to make, professions to pursue, taxes to file. Someone named “Mrs. Watson”, the identity of whom I now have no idea but who was probably the administrative assistant to some academic dean, gets innumerable mentions. Yet the only thing I was really thinking about, I mean really, was the person who would later become my wife [below, in a picture from the time]; and how she fit in with some possible other person, and so on.

What I am saying is that my little notebooks carry a “front story”, i.e., “process”, “Mrs. Watson”, and getting into some program or school; and they carry a “back story”, i.e., the core relationship of my future life.

But which was really “back” and which was “front”? It was the opposite of what I thought at the time. The career story was the back story, tho' I conceived it to be the front. The Love Story was the front story, tho' I thought it was the back.

This is a lesson for me from life. If only I could go back to 1973 and live the right emphasis. Just like in Super 8, what you think is the back story is really the only story. [Below, Paul in the Seventies:]

Each of the four times (so far) that I have seen Super 8, I have come home from the theater and dug out my old issues of Famous Monsters. Like the Aga Khan, they are worth their weight in gold. I even found a second issue that had been autographed by Forrest J. Ackerman on the Sacred Day that Lloyd Fonvielle, Bill Bowman, and I were invited to lunch with him.

That's reality. That's the front story. If I could only go back to the future.

. . . to think about Jane Greer, coming out of the sun into La Mar Azul.

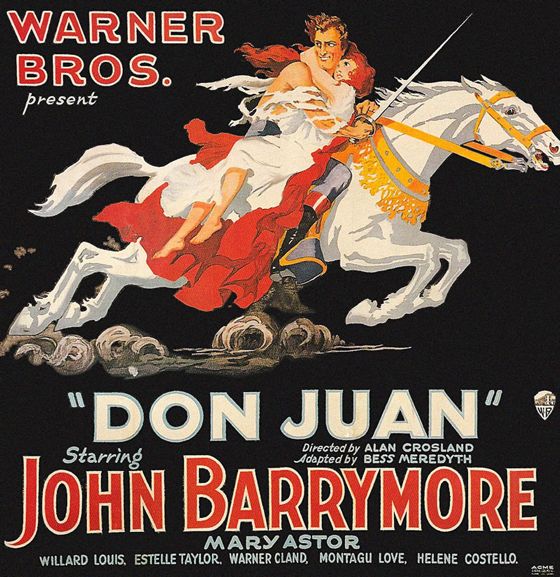

Directed by John Ford, 1926.