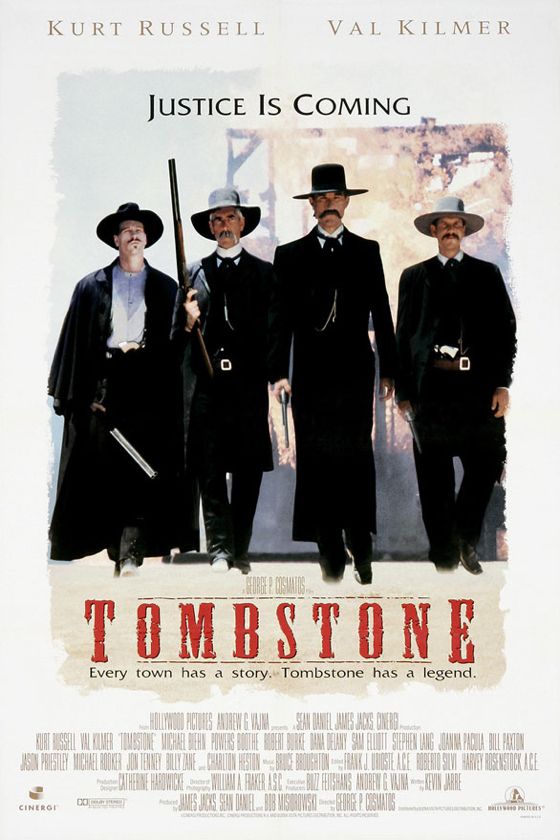

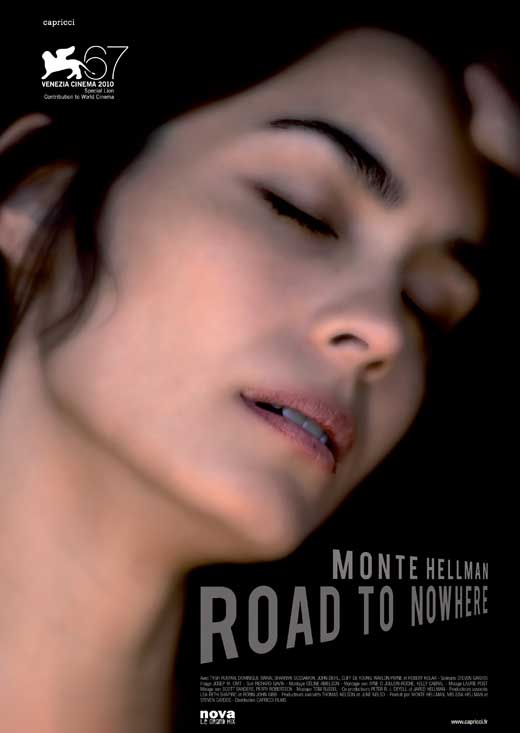

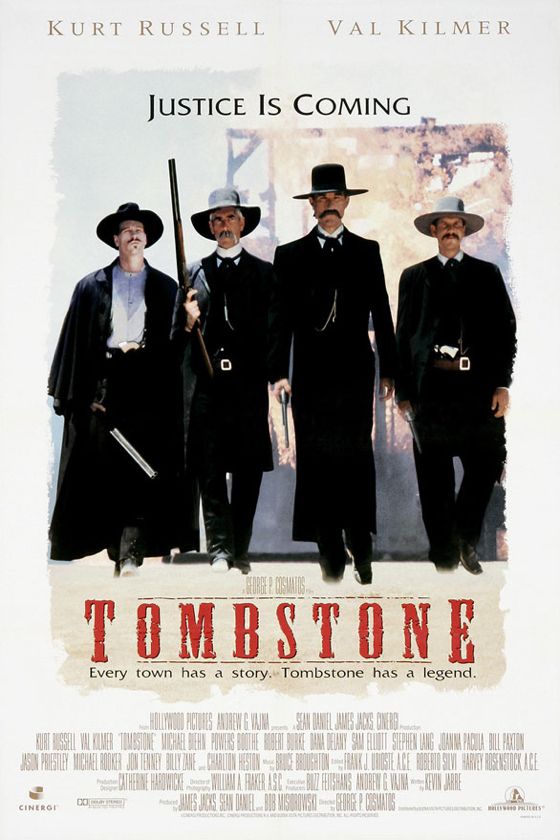

In the wake of my friend Kevin Jarre's recent death, I decided, fearfully, to re-watch the movie that might have been his masterpiece, Tombstone, released in 1993 as “A George P. Cosmatos Film”.

I watched it for the first time, when it came out, in a state of sorrow, but this time I watched it in a state of rage. Then, one could see it as a lost opportunity for cinema, for the Western, and for Kevin. Now that he's gone one has to view it as the last opportunity for Kevin, who had the ability once to resuscitate not just the Hollywood Western, but Hollywood itself.

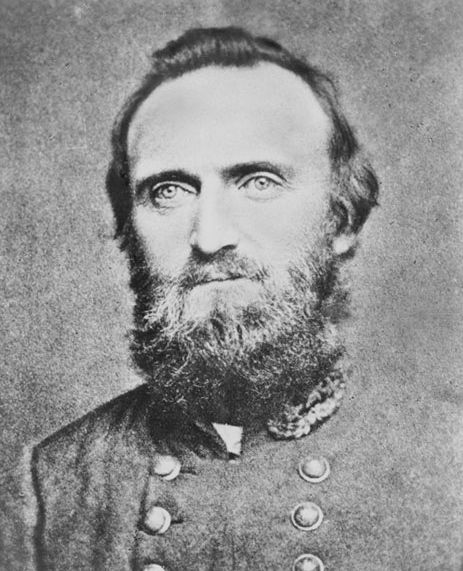

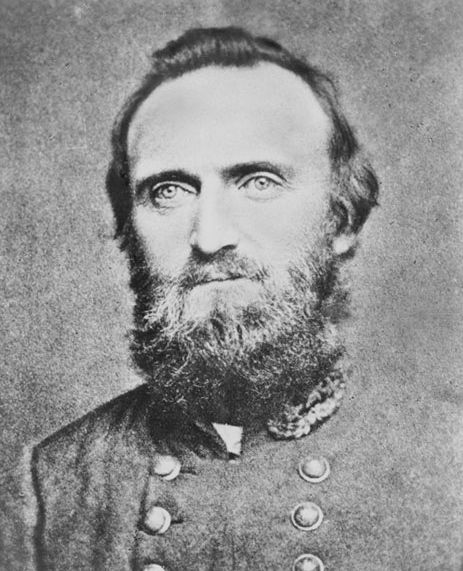

When I read his original 138-page draft of the script, not long before Kevin went off to start directing the film, I believed I had encountered something momentous. “This movie,” I said to him, “is going to be like Jackson's flank march at the Battle of Chancellorsville.” That march was a recklessly bold move by most of Lee's available forces to strike the rear of the overwhelmingly superior Union forces confronting him. While Jackson was on the move, Lee would be totally vulnerable to even a modest Union advance. If the march had been detected while in progress, Lee's whole army could have been crushed in detail.

It was not detected, it took the Union forces totally by surprise and sent them into a full-on rout. It turned what was a stalemate at best into an impossible victory.

I associated this with the movie Kevin was about to make because I knew that Kevin had conceived of a film which would be both stunning, artistically, and wildly commercial. Hollywood would not know what had hit it. Kevin had revived the craft of storytelling from Hollywood's Golden Age, brought it forward into the modern era and opened a way back into films that were both entertaining and powerful, exhilarating and profound.

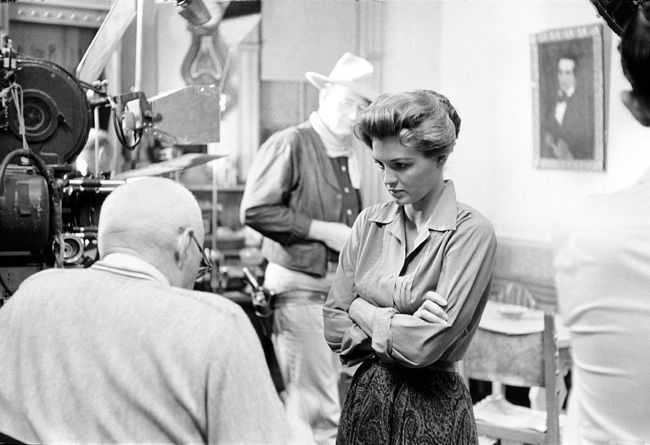

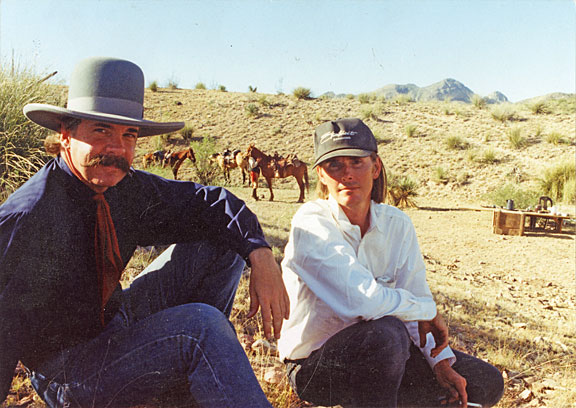

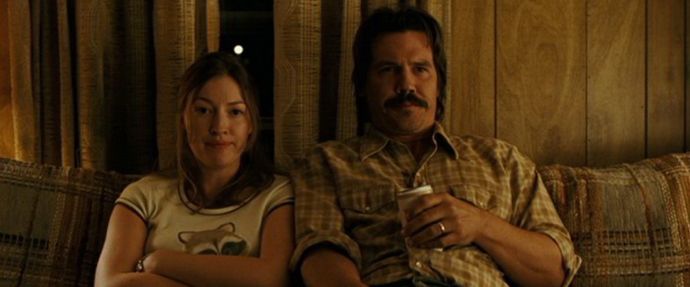

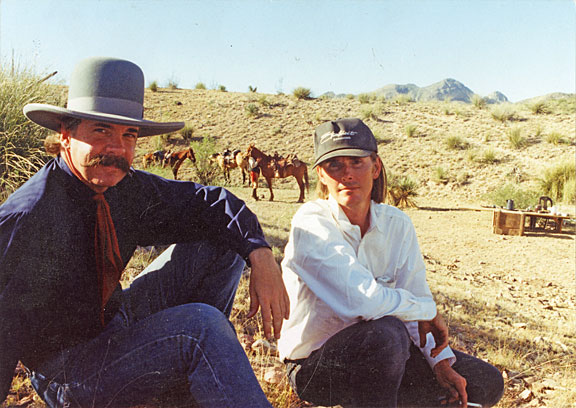

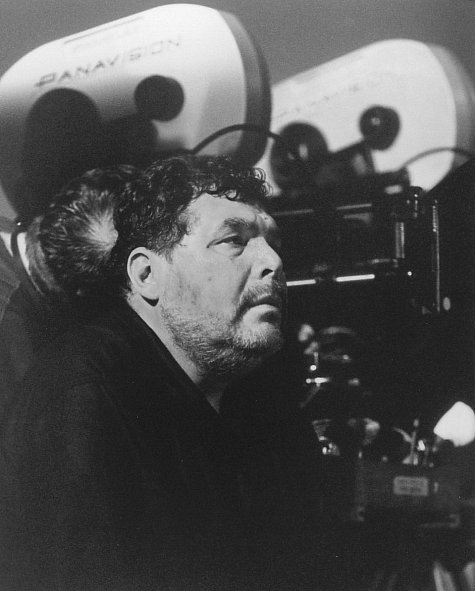

Kevin (above right, on the set) lasted only a few weeks as director of the film. I can't say of my own knowledge why he was replaced. There are stories of eccentric behavior on his part, and of falling behind schedule. I do know that the power on the production shifted to mediocrities, and that they trashed his vision. Enough of it remained to make the film beloved by fans of the Western and a solid hit at the box office, but enough of it remained also to make clear what it could have been.

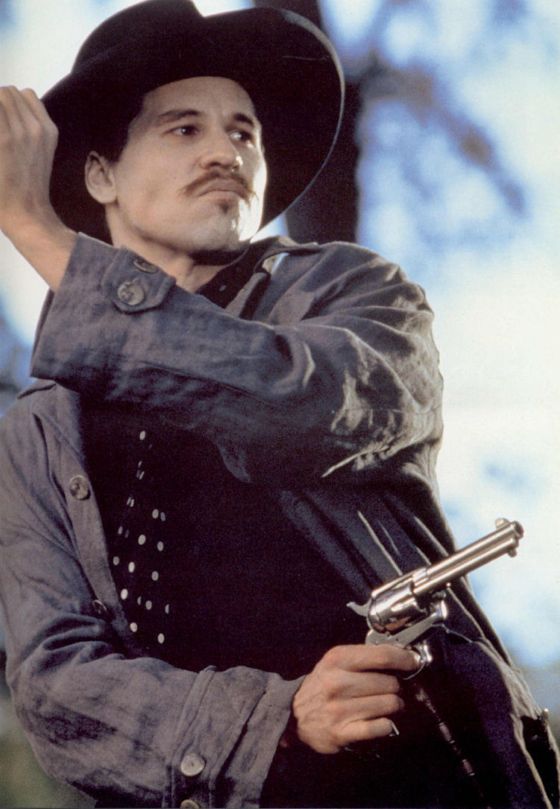

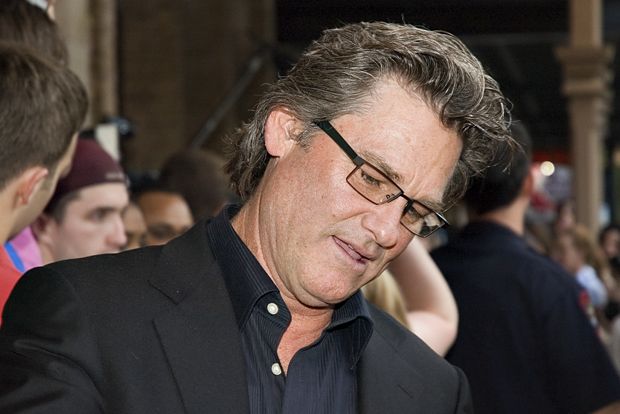

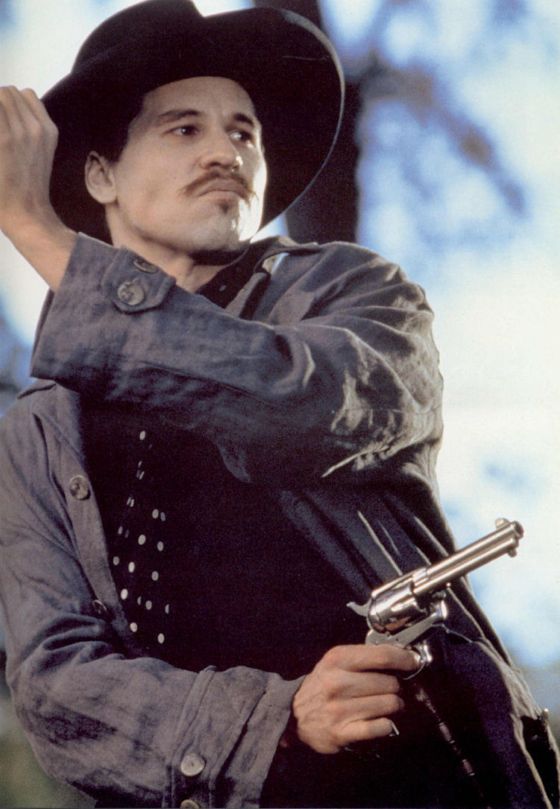

Kevin cast the film, of course, and supervised the design of the production. Every choice he made on those fronts was pitch-perfect. Some of the footage he shot remains in the film, and all of it is breathtaking, worthy of John Ford, a comparison I don't make lightly. The rest of the film looks like crap, like a high-class TV movie. About 30 pages of Kevin's script were discarded, and Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer worked with the director who replaced Kevin, George Cosmatos, and with a journeyman screenwriter named John Fasano to “improve” existing pages.

Everything done after Kevin was fired cheapened and diminished the film. After the film was favorably received by critics and audiences, the mediocrities were proud to take credit for the cheapening and diminishing, as though these things had actually been what “saved” the picture and made it work.

These people didn't just want to take the miraculous gift Kevin had given them — they wanted to pretend that they had given it to themselves.

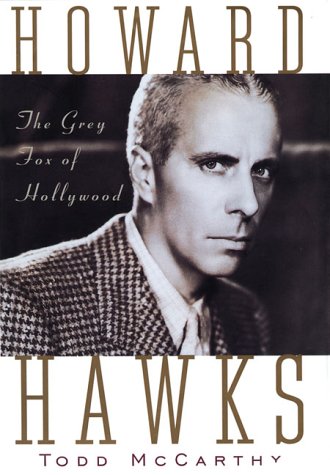

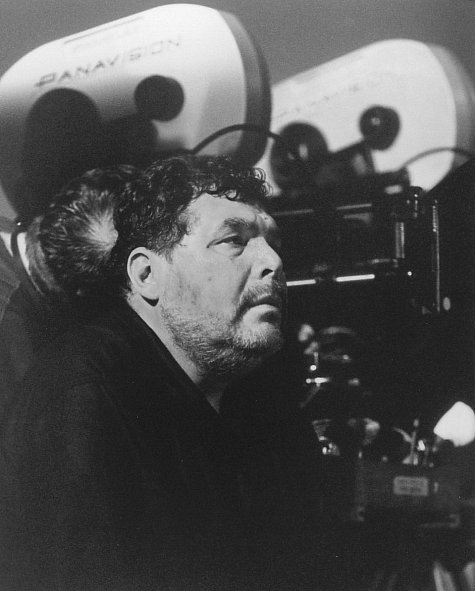

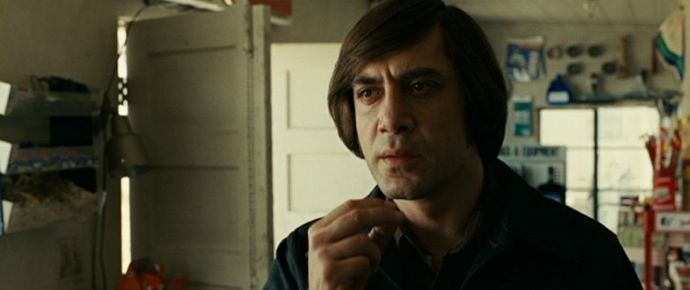

In his director's commentary on the DVD, George Cosmatos (above) takes full credit for the historically authentic details of the story and look of the film, even though he had nothing to do with these things. He also reveals the secrets of his approach to shooting the film, which involved using multiple cameras to record each scene, so the editor could make the choices he didn't know how to make on the set, and varying the style of the shots as much as possible, to create “interest”. This is the craft of a journeyman, at best. Cosmatos was a competent journeyman.

After Cosmatos died, Kurt Russell “revealed” that in fact he himself had directed the film after Kevin left, using Cosmatos as a front. He did it by stealth, giving the stooge Cosmatos shot-lists the night before each day's work and executing his ideas on the set by a series of hand signals he and Cosmatos had worked out. This would constitute the first time in film history that a movie has been secretly directed by someone without anyone else on the production suspecting the fact. The idea that you can direct a film with shot-lists and hand signals is beyond ludicrous — it's pathetic.

Russell and Cosmatos seem to have known so little about what directing a film actually entails, or I should say what directing a film well actually entails, that they may have believed their sad fantasies of themselves at the true auteurs of Tombstone. In any case, Cosmatos probably knew he could get away with retailing his fantasies on the DVD because Kevin was never much interested in re-fighting the battle of Tombstone in public. Russell certainly knew that he could get away with trashing Cosmatos's contribution to the film, such as it was, because Cosmatos could not argue back from the grave.

I knew Cosmatos slightly, and I know he was extremely proud of having directed Tombstone. It's not easy to replace a director while a shoot is in progress, and Cosmatos got the job done, however one might evaluate the quality of his work. I have a lot of respect for Russell as an actor, and he gave a fine performance in Tombstone — but even if he did secretly direct the very badly directed film, the fact remains that decimating Cosmatos's legacy the way he did, when Cosmatos was no longer around to defend it, strikes me as just this side of nauseating. Russell should have put his name on the film as its director or kept his mouth shut. If the film had tanked at the box office and had no reputation today, I strongly suspect that he would have kept the secret of his extraordinary accomplishment to himself.

People are used to merely throwing up their hands at dishonorable behavior like this because “it's just the way Hollywood works”. But it only works that way because enough people throw up their hands, and in many cases actually respect the yacks for possessing enough power to behave like insolent curs and get away with it.

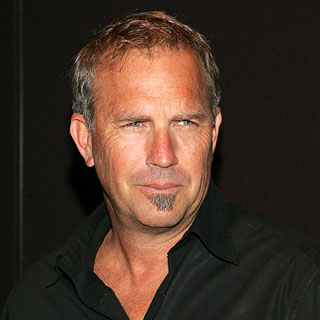

In the interview in which Russell revealed his secret authorship of Tombstone, he said he respected Kevin Costner for trying to prevent the release of Tombstone, so it couldn't compete with Costner's (far inferior) version of the tale, Wyatt Earp. “He was playing hardball,” Russell said. No, he wasn't playing hardball. In hardball, as Earl Weaver once said, “you've got to put the ball over the plate and give the other fellow his chance”. Men play hardball. Collapsed males play the Hollywood game.

I think the rage I felt watching Tombstone again is useful — following the principle that “the tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”. The moment has come when filmmakers, and the culture, need to say, as Wyatt Earp says in Kevin's script, when he's had enough of the insolence of the curs, “You tell 'em I'm coming . . . and hell's coming with me, you hear? Hell's coming with me!”

Anyone who has a problem with this can step right up and get their time. I'm your huckleberry.