They kidnapped the cinema, but we’ll go after it, and we’ll find it in the end, I promise you. We’ll find it. Just as sure as the turning of the earth.

Click on the image to enlarge.

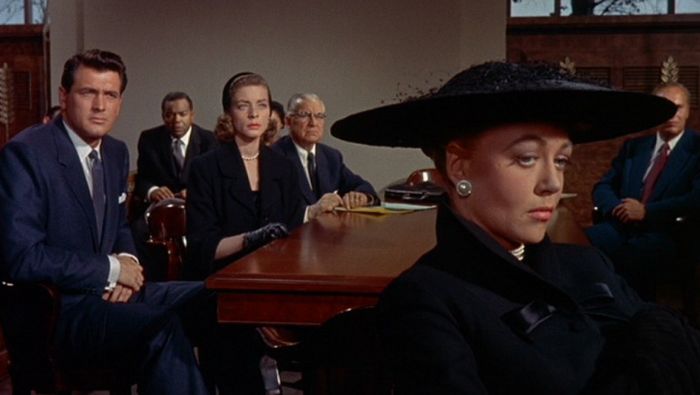

In Douglas Sirk’s movies the women think. I haven’t noticed that with

any other director. With any. Usually the women just react, do the

things women usually do, and here they actually think. That’s

something you’ve got to see. It’s wonderful to see a woman thinking.

That gives you hope. Honest.

— Rainer Werner Fassbinder

I think this is a profound insight. Most movies are made by men, and men are obsessively, if quite naturally, interested in what women think of them, and of other men. However sympathetic they may be to women, they are not much interested in what women think about other things than men, or in the thoughts of women which cannot be influenced by male behavior.

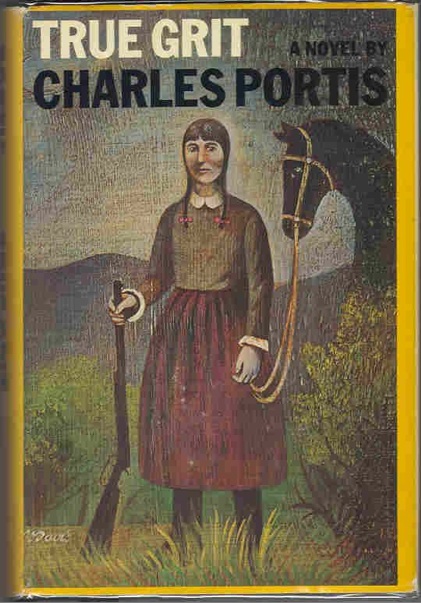

I am trying to think of exceptions to Fassbinder’s rule, and I can’t come up with much. I think we see Mattie Ross in the Coen brothers’s version of True Grit thinking.

I think we see the old and the young Rose in Titanic thinking.

I think we see Barbara Stanwyck thinking in almost every role she ever played, regardless of the lines she was reading and regardless of who was directing her.

Some other icons of female independence, like Katherine Hepburn, always seem to be reacting to men on some level, saying, in effect, “See how much I don’t need you?” — which of course is just a way of saying, “You’re going to have to come and get me.” This I think falls into the category of reacting, of doing the things women are expected to do.

Greta Garbo is an anomaly. She rarely seems to be thinking anything, even in reaction to what men do, which allows us to project thoughts into her. I wouldn’t say that we ever see her thinking, but it’s possible to imagine that we do. In a way, this is the source of her whole mystique.

I think we can see Vera Miles thinking in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence — we have to, really, because the whole truth of the film is located in her thoughts, which are never verbalized.

In odd moments here and there, in films which are dominated by a male viewpoint, we can see women thinking — in On the Waterfront, for example, we can see Eva Marie Saint thinking occasionally.

In The Palm Beach Story, Preston Sturges sometimes lets us see Claudette Colbert thinking.

It’s in musicals, curiously, in song and dance numbers, that we can most often see women thinking — Judy Garland, Eleanor Powell, Ginger Rogers, Cyd Charisse. Powell and Charisse in particular never seem overly concerned with manipulating or reacting to what men think of their sexuality — they seem to be enjoying it for its own sake, thinking about it in their own terms.

That’s about it.

I'm living it, folks . . .

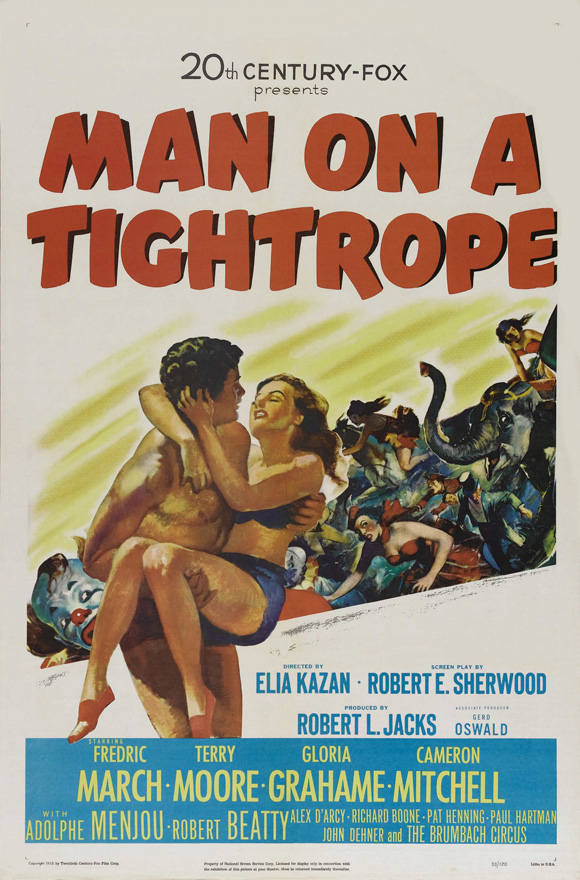

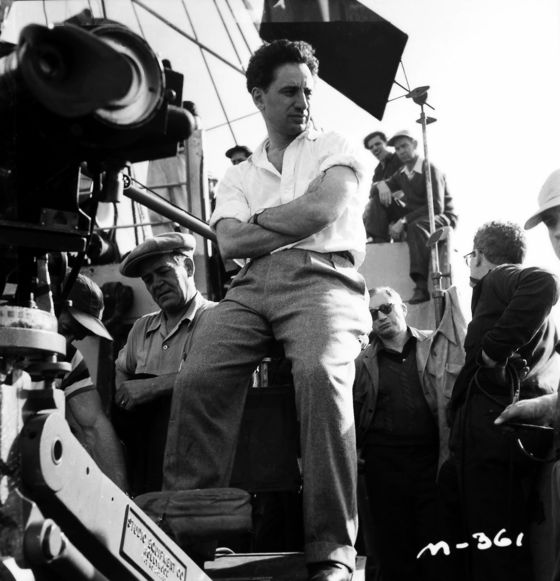

I’d never even heard of Elia Kazan’s Man On A Tightrope until I encountered it in the new Elia Kazan Collection DVD box set, so I was a little surprised to discover that it’s a minor masterpiece. Kazan dismisses it as a misfire in his autobiography, probably because Daryl Zanuck took it away from him and edited it himself. Kazan didn’t like what Zanuck had done with it, and when it flopped at the box office, he may have just wanted to forget it.

It doesn’t deserve to be forgotten.

If Ingmar Bergman had ever made a cold-war thriller, it would probably have looked a lot like this film. It’s about a shabby little circus troupe behind the Iron Curtain which plans to escape across the border to freedom in the West. According to Kazan, Zanuck cut the picture to emphasize the suspense element, losing a lot of Kazan’s nuance and atmosphere, but the truth is that it works as a thriller and has plenty of nuance and atmosphere — beautiful and surreal images of the circus world that elevate the film into an eloquent metaphor for artists struggling to escape restraint.

Frederick March gives one of his best performances as the leader of the circus — quiet, understated, touching. Gloria Graham is as vexing as she often was as his wayward wife and Adolph Menjou has a brief but effective turn as a Communist internal security operative.

The film was shot in Germany, mostly on location, and looks terrific, blending the poetic and the documentary with a sure eye.

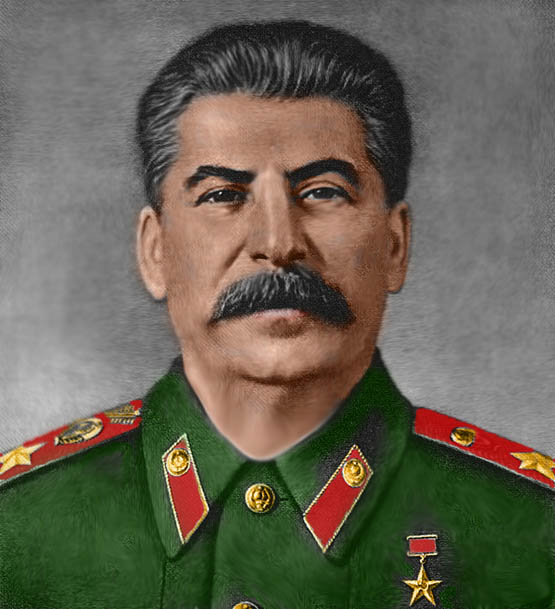

It was the first film Kazan made after naming names before HUAC and earning the eternal enmity of progressives, but the interference with the arts depicted in the film echoes the interference attempted on American soil by the members of the American Communist Party whom Kazan “betrayed” to HUAC. It was this interference which caused Kazan himself to leave the Party in the 1930s, and Man On A Tightrope was a kind of defiant defense of his actions, then and later. It reminds us that, however opportunistic and hypocritical the Communist witch hunters may have been, they were hunting real witches — real and ruthless apologists for Stalin and Stalinist methods.

That ought to be taken into account in judging Kazan for “ratting them out”, but none of it needs to be taken into account in appraising Man On A Tightrope, which is a fine and masterful work of art.

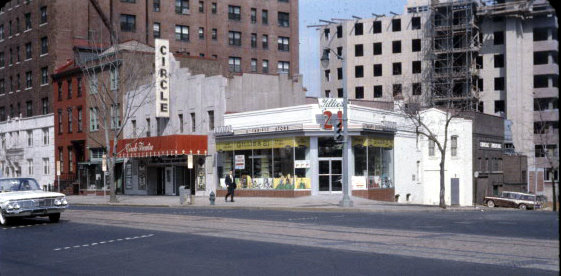

In a recent episode of PZ's Podcast, my friend Paul Zahl paid tribute to The Circle Theatre in Washington, D. C., a now vanished palace of dreams where he and I first encountered foreign films. It was in the early 1960s and we were about 13 years-old at the time, living in an age before cable and home video, when finding “art films” required the sort of effort usually associated with obtaining illegal drugs or firearms.

I'm not really sure what drew us to The Circle, an art house cinema — we were monster movie fans at the time — or what we thought we would find there. We didn't know anyone who either knew or cared much about “art films” and we certainly didn't know anyone who thought they were cool. I know that what we did find at The Circle was a series of revelations about the possibilities of movies, and glimpses of adult sexuality, and the beginnings of lifelong passions for the French New Wave and the works of directors like Ingmar Bergman and Roberto Rossellini.

The Circle was demolished years ago and youth has long since fled, but the wonders we encountered at that theater remain as bright as when we first beheld them.

Listen to Paul's podcast here — The Circle.

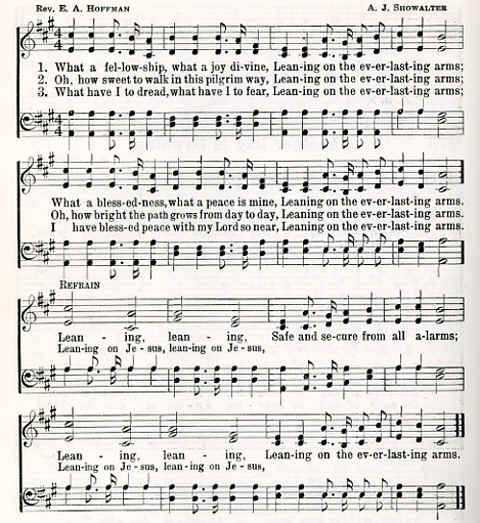

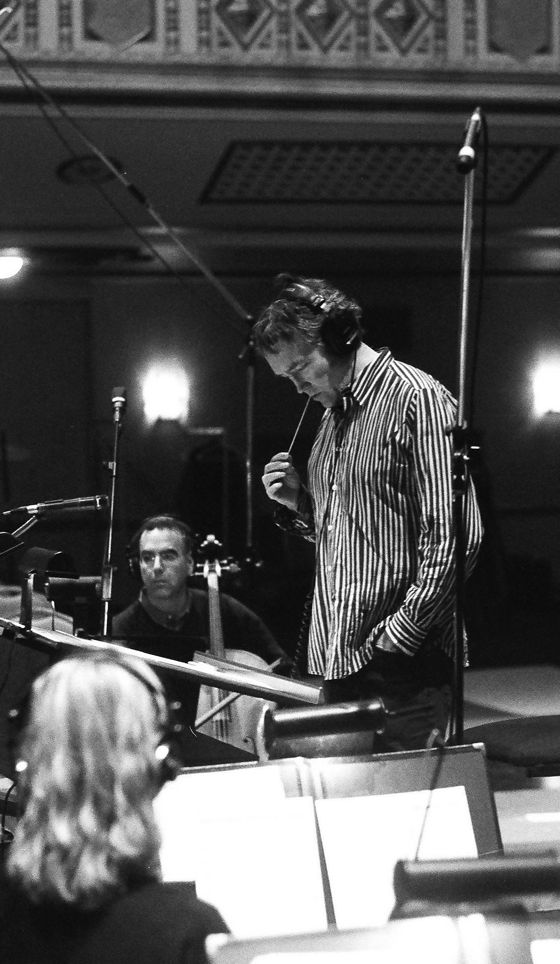

Carter Burwell's score for the Coen brothers' True Grit is one of the finest of recent times — a score inseparable from the film's emotional impact and moral meaning. It's therefore ironic, and actually insane, that it was deemed ineligible for an Academy Award for best score, because it is largely based on themes from old hymns.

From the time of Bach to the time of Bob Dylan, putting old tunes to new uses has been an important part of the work of many great composers. It is, paradoxically, an endeavor in which a composer can most clearly demonstrate his or her originality. Presenting familiar melodies to us in ways that renew them, allow us to hear them in new ways, requires a high degree of imaginative skill.

In his score for True Grit, Burwell works with hymns that are hardly central to the culture these days, but still linger in the collective memory. He rings variations on their melodies that are intimately tied to the moods and themes of the film, and link the film to the musical heritage of America, as the film itself is rooted in the history of the nation and echoes the history of the Western film genre.

Burwell's elegant arrangements don't trade in nostalgia, however, but evoke the severe and demanding faith of 19th-century America — the faith of the film's central character, Mattie Ross. They evoke the grandeur and the dignity of virtue and aspiration, not the narcosis of religious “comfort”. They harken back, as the film does, to what Greil Marcus calls “the weird old America” — the funky, scary, endlessly strange America of a relentless, antic, eccentric people who dreamed majestic things and then cobbled them into existence by any means that came to hand.

Burwell's arrangements have the flavor of the parish hall, of music made communally — simple and unadorned, but inexorable. There is no hint of pastiche about them, or of antiquarian reconstruction — they channel the pure spirit of the frontier.

“Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” is the central hymn in the score — it is associated with the “father theme” of the film. We hear it played on a piano over the opening shot of Mattie's murdered father, and then in moments when Rooster Cogburn and Ranger La Boeuf make emotional connections with Mattie, becoming the substitute fathers she so desperately needs. This is an unspoken theme of the book and the movie — speaking it out loud would have turned True Grit into a Disney film, but speaking it in music offers a subliminal and potent emotional reinforcement.

Wisely, Burwell doesn't use “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” for the climactic set-pieces of the film — he switches gears to strike a bigger and more decisive note. When Rooster rescues Mattie from the snake pit, Burwell uses the melody of “Hold On To God's Unchanging Hand”, which we've heard once before in Mattie's great moment of heroism when she swims Little Blackie across the river, and first earns Rooster's admiration (although he admits to admiration only for her horse.)

The orchestration in the river crossing scene

is grand and noble, almost stately. It does not try to sell the excitement

and danger and suspense of what Mattie is doing, but to emphasize the

magnificence of her courage. It seems to summon up the whole epic sweep

of America's westward progress, and the thrill of every river crossing

in the history of Westerns. It's music that orients us morally to the

scene it's accompanying.

Using the theme again in the snake pit scene reminds us that Rooster's heroism there is on some level a response to Mattie's heroism — an attempt to honor it.

Film scores, especially today, don't often provide this sort of complex resonance with a film's themes — they usually just underline the immediate sensations of the scene in front of us. Burwell is collaborating with the Coens on a profound level here — making the score a participant in the construction of the meaning of the film. It's a stunning achievement, and the Academy has disgraced itself by failing to appreciate it.

Burwell or the Coens made an inspired choice by playing Iris Dement's recording of “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” at the film's close. Her performance is very powerful, accompanied by a simple piano and guitar arrangement. Her vocal is both raw, down-home, and beautiful, soaring — she seems to be singing to us from the heart of the 19th Century.

The score is a fine one to listen to on its own, but for some reason the soundtrack CD doesn't include the Dement recording. It's included as a bonus if you buy the album on iTunes, but only in the abridged version used in the film itself. For the full recording, it's worth tracking down Dement's album of sacred songs, Lifeline, which also features a sublime version of “Near the Cross”.

In her liner notes for Lifeline, Dement says, “These songs aren't about religion. At least to me they aren't. They're about something bigger than that.” The same might be said of the hymn tunes Burwell has adapted so brilliantly in his True Grit score. They resonate on many different levels at once, as the music for any great film score does.

[Image © The Los Angeles Times]

[Image © The Los Angeles Times]

I’ve seen True Grit three times now. I

liked it better the second time than the first, and I liked it better

the third time than the second — although on the third viewing I managed

not to cry until the very end.

I saw the film at three

different theaters, each of which had digital projection. At the first

two theaters the image looked mushy at times, and slightly washed out

in certain scenes. I assumed this was due to the digital nature of the

presentation, but it wasn’t that, because at the last theater the film

looked spectacular — almost like a photochemical print. I could tell

that the movie was beautifully composed and lit on my first two

viewings, but on the third I really got to enjoy the beauty of it in a

more sensual way.

Hailee Steinfeld’s performance seemed

richer and more nuanced this time. The Coens obviously steered her

into doing less than she might have — going for bigger effects might

have exposed her inexperience as an actor — but holding back was also

right for the role. Once you realize how perfectly pitched her

performance is, how complex her reactions really are, you start paying

closer attention to her, and reacting more emotionally to what she’s

doing.

I loved sitting through the previews this time,

because they were so ghastly, like transmissions from another universe

than the one True Grit inhabits. All the “coming

attractions” looked like movies that have already been made, over and

over again — the products of that eternal circle-jerk that is

modern-day Hollywood. When True Grit comes on, you see an

original work of art — based on a novel, and the second film version

of that novel, but alive with new invention and new energy. It’s a

film that will always be brand new.

I think it’s one of the greatest Westerns ever made, worthy of Mann and Boetticher and even Ford — yes . . . even Ford.

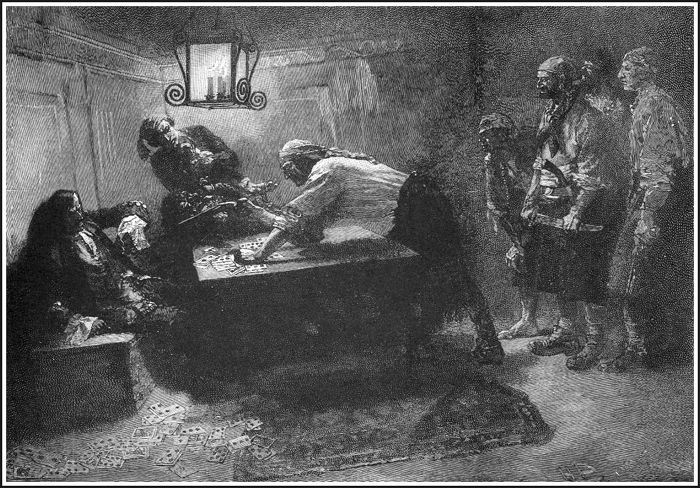

As kids, Joel and Ethan Coen were obsessed with the works of Howard Pyle and his disciple N. C. Wyeth. They were especially fond of the image above, one of those collected, after Pyle's death, in Howard Pyle's Book Of Pirates. They reconstructed a version of the scene in True Grit — in the cabin where Rooster and Mattie are holding the two captured outlaws.

Pyle was a very great artist, and once highly regarded — Vincent van Gogh told his brother that Pyle's work struck him dumb with admiration. He is not as well regarded today — there are no first-class collections of his work in print — but Victorian academic art continues to inform the great visual artists of the cinema, if only at second or third hand. John Ford would have known Pyle's work well, and if the look of True Grit reminds you of the look of a Ford film, it's in part because Ford and the Coens all learned from the dynamic and dramatic compositions of Pyle and his followers, so powerfully “cinematic” in their effects.

This is Harry Rossi's third Majestic Micro Movie, and his best.

Watch it here — Hay

The Coen brothers' version of True Grit opens with a slow track in on a man lying dead on a street in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in the 1870s. In a voice-over, an older woman recounts the details of the man's death. He was her father, and was shot down in cold blood by his hired hand, who then fled into the Choctaw Nation, beyond the reach of Arkansas law. She, at the age of fourteen, decided to go after the man and bring him to justice. Snow falls over the body, and snow will be a recurring visual motif in the film that follows. It will become a quiet emblem of grace in a tale of violence and revenge.

The slow tracking shot and the narration and the gentle snowfall ask us to settle back and concentrate . . . on a story that will take its time in the telling, as most good stories do. Joel and Ethan Coen are asserting that they have a real story to tell, a story worth hearing, and this assertion comes as shock in the context of most movies of our time, which assault us furiously with fast cutting and loud sounds, trying to get our attention by crude means, usually to hide the fact that that there will be no story on offer — just a series of sensations.

Everything about this film asks the audience to step forward towards it, to pay attention, to look for a personal reaction instead of a reaction prefabricated by the filmmakers. Those whose perceptions have been dulled by the sensory assaults of modern films, or whose imaginations have been crippled by stories which are not really stories but just a collection of incidents, may find themselves a bit put out. The rest will find themselves embarked on a great adventure — not just as spectators but as participants.

Visually, the film is structured around shots — beautiful images of deep spaces that we can enter into imaginatively. This is extremely rare in modern films, which are generally structured around rapid sequences of shots, none of which is interesting or seductive in itself — it's only the fake excitement of the cutting that we're meant to respond to. This works the way the spiel of a three-card monte dealer works — to distract us from the flim-flam he's trying to put over on us with his sleight-of-hand.

The performances of the actors make no explicit appeals to our judgment or affections. Jeff Bridges, as Rooster Cogburn, snarls and mumbles his lines as though he doesn't much care if he's understood — but it's Cogburn who doesn't care, not Bridges. Bridges is simply thoroughly absorbed in Cogburn.

Matt Damon, playing a Texas Ranger named La Boeuf who's a bit of a dolt, never puts quotes around his bombast or his insecurity, to let us know that he, Damon, is not that sort of fellow. He puts the fellow before us as he is, with absolute conviction, and this makes for a spectacular pay-off when La Boeuf proves his mettle at the film's climax. Having allowed us to take his faults seriously, Damon also allows us to take his redemption seriously.

Hailee Steinfeld as Mattie also makes no direct appeal to our goodwill. Mattie is a pill in many ways, a plucky but very cold and judgmental little girl. Her need and fear are never emphasized, her love for Cogburn is never articulated or sentimentalized in any way. We are given the space to feel her emotional odyssey because we haven't been prompted to read it as such, haven't had our noses rubbed in it.

Almost every moment in the film that might have been milked for an obvious audience response — like Cogburn's heroic ride against the four bad men — is all but thrown away, in the sense that we aren't provided with that extra note of emphasis reminding us of the import of what we're watching, that little pause in which we're meant to cheer. The tale proceeds as if it were happening without us, and that, by the paradox of storytelling, draws us deeper into it. It's a tale that blossoms and clobbers us over the head only at the end of it, perhaps only after we've left the theater, resonating like a real experience of real things.

If you find, after seeing the film, that you love Mattie Ross and Reuben Cogburn and Ranger La Boeuf, it's not the result of a story committee in Hollywood telling you that they're lovable — it's the result of something that has happened in your own heart.

It takes a lot of skill to tell a story this way. In the modern age, it takes even more courage. Hollywood hates and despises its audience — believes it brings nothing to a film, except perhaps a recognition of the name of the property that's been adapted to the screen, and certainly not a human heart.

The Coen brothers, in True Grit, imagined an audience made up of real people, with real emotions, real moral and spiritual concerns — an audience that would bring as much to the table as their film brought, ready for a conversation about serious and wonderful things.

As it turns out, there was such an audience out there, ready for such a conversation — which is why True Grit became a surprise hit over the recent holidays. That audience is still there. It is still ready. You can be sure, too, that Hollywood still hates and despises it, which is why, increasingly, audiences hate and despise most of what Hollywood has to offer. Movie attendance in 2010 was the lowest it's been in fifteen years.

It's easy to see where this trail is heading — and it's not Hollywood's way. The major studios still have a practical veto power over what films audiences will see — but only in the short term. In the long term, audiences will have an even more efficient veto power over Hollywood, and everything that Hollywood represents.

The Coen brothers are known for their dark humor and bleak view of the world, but in recent years they have become increasingly obsessed with the mystery of goodness. In the desolation of a North Dakota winter, vicious killers stalk the land, and there suddenly is Marge Gunderson, a paragon of decency and courage. Why? Why is there a Marge Gunderson?

This is essentially a religious question, in the sense that it has no logical, rational answer. The temptation of theology is to supply logical, rational answers to religious questions, but it's the unanswerable questions that move the heart and change lives. That's why the Bible is long on stories and short on theology, why Jesus taught with parables instead of intellectual arguments.

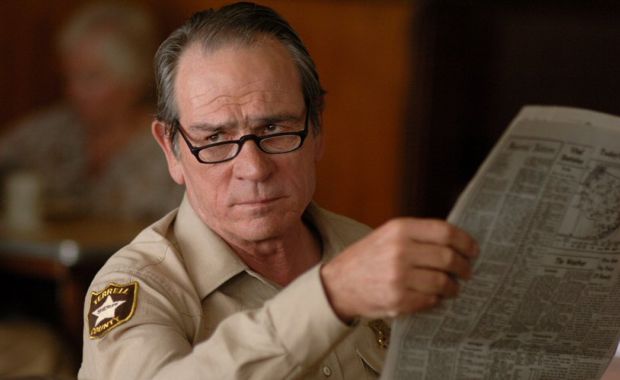

The Coen brothers' film No Country For Old Men is almost a reprise of Fargo — without the comedy this time, and with a much darker and more terrifying view of the evil stalking the borderlands. The figure of the good sheriff, played by Tommy Lee Jones, who seems to stand alone against the horror, is even more mysterious than Marge was.

He seems to possess some supernatural power over the Bardem character's pure wickedness — his very presence seems to be able to make the Bardem charcter vanish into thin air — but it's a power that even the Jones character doesn't understand. There is a suggestion that his decency and courage are outdated virtues, on the verge of being overwhelmed by the world's evil. And yet they linger . . .

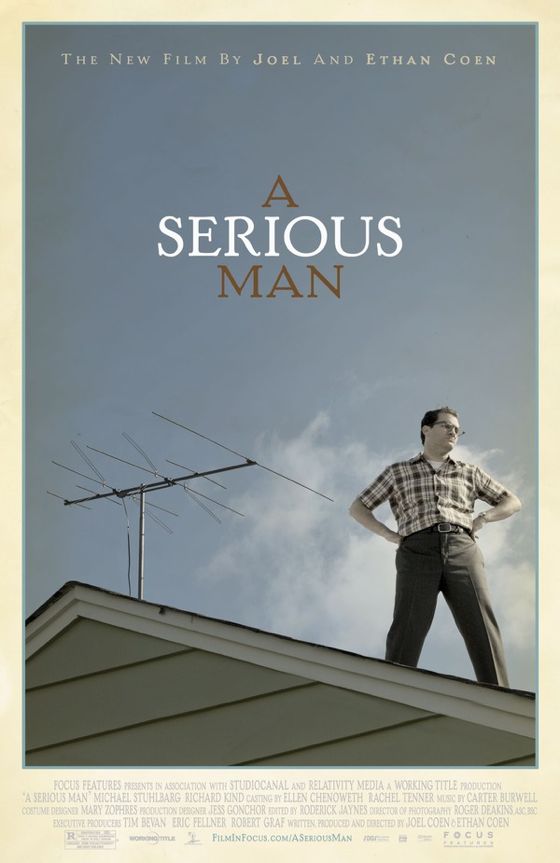

In A Serious Man, the Coens take on the Book Of Job, the Bible's great story of a man who clings to righteousness in the face of an implacably destructive universe. It makes no sense — it is, yet again, a mystery to be puzzled over.

In Charles Portis's novel True Grit, the Coens found a text ideally suited to their late-period themes. A self-righteous and vengeful little girl meets up with a violent and none-too-virtuous law officer, and somehow they find a way to love each other. Their mission of harsh justice is infected with grace, a grace neither of them really understands, except on a level beneath conscious thought. They part ways after their adventure, but the little girl lives the whole rest of her life in the glow of one great act of love on the part of the least likely of men . . . a kind of redemption for both of them by the unexplainable appearance of goodness.

The Coens use the hymn “Leaning On the Everlasting Arms” as a musical motif throughout the film, and Iris Dement's recording of it comes at the film's end, summing it all up in a way. The phrase “everlasting arms” is from the Old Testament, and is used in the hymn as an image of Christian salvation, but the use of the song here is not theological in any sense. Mattie Ross's conscious religion is cold, judgmental and unforgiving — Rooster Cogburn's religion is non-existent. There is no theology in what saves them, because what saves them is irrational. The everlasting arms are just there, without explanation — the way Marge Gunderson is just there.

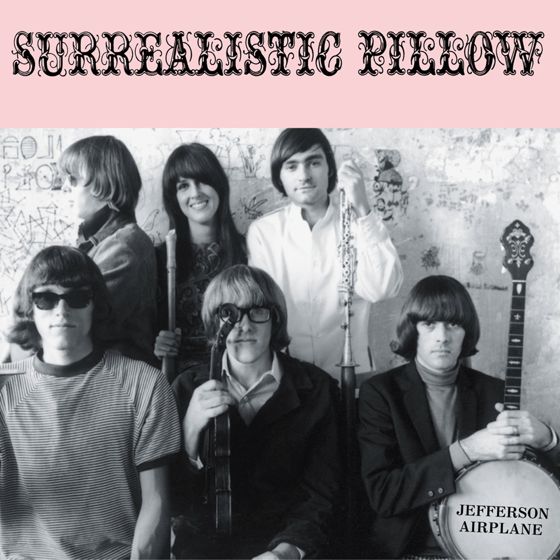

A key to all this can be found in the figure of Rabbi Marshak in A Serious Man. He is the ancient and remote fount of all wisdom, but unavailable to the film's Job figure, who can't get an appointment to see him. But his son is granted an interview after his bar mitzvah. The old sage sighs and then, improbably and hilariously, quotes a line from a Jefferson Airplane song — “When the truth is found to be lies . . .” And just when you expect wise council on this subject, the rabbi breaks off, trying to remember the names of the members of the Airplane.

So much for wisdom — almost. Ending the inscrutable interview, the rabbi gives the kid a portable radio, and says, “Be a good boy.” So — when the truth is found to be lies . . . be a good boy.

There is no suggestion that this will restore truth to the world, or make a triumph out of life. It's more a statement of faith — that goodness, like the Dude, abides, and that it may be the only mystery worth contemplating.

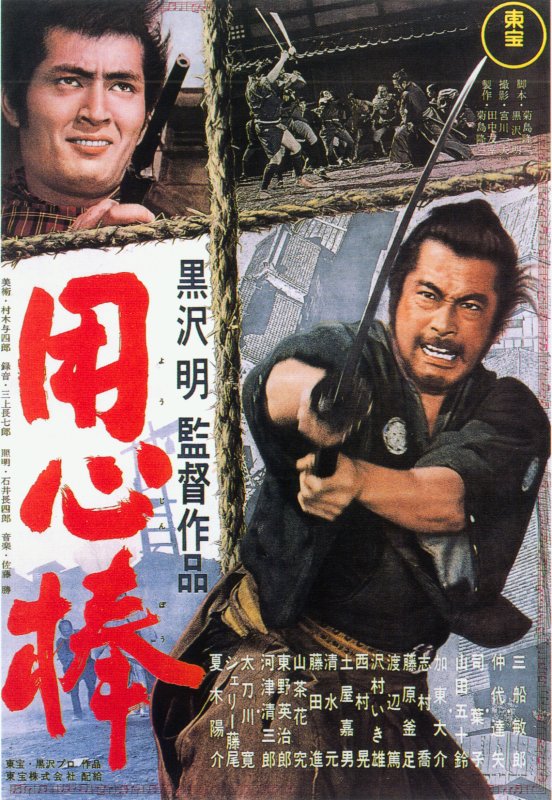

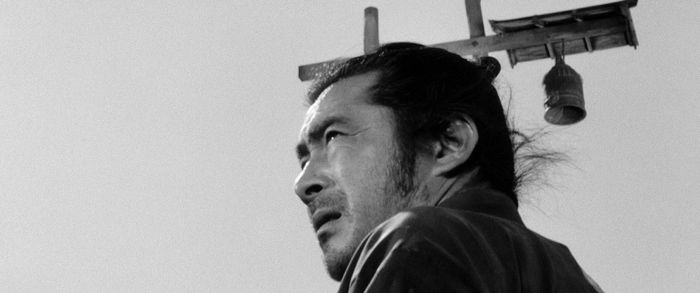

It's well known that Sergio Leone stole the plot of Fistful Of Dollars from Kurosawa's Yojimbo, transposed it to the Old West and gave birth to the Spaghetti Western. Leone's film was a big hit worldwide, and in a legal settlement over the plagiarism, Kurosawa was awarded the revenues from the film in most Asian markets. Yojimbo had a been a big hit itself, mostly in Japan, but the profits to Kurosawa from Fistful Of Dollars exceeded those of the original by a considerable degree. Kurosawa always regarded this as a stroke of great good fortune.

Leone fans like to point out how much he added to what he took from Kurosawa, but in fact it was very little. Everything that's most startlingly “original” about Fistful Of Dollars was already present in the film it was based on. The quirky visual style, mixing views of deep spaces with extreme and iconic widescreen close-ups, the jangly score, with odd instrumentation and occasional bombastic flourishes, the whole sardonic attitude towards genre, were invented by Kurosawa. Calling Leone's style “operatic”, and thus linking it to specifically Italian sources, ignores the fact that Yojimbo is just as “operatic” in just the same ways.

Kurosawa's film was extremely radical for its time. He was trying to re-imagine the samurai film, invest it with a modernistic attitude, while at the same time delivering the reliable pleasures of action set-pieces, but action set-pieces that were even bolder and more dazzling than those usually found in the genre.

As part of his strategy, Kurosawa emphasized the link between samurai films and American Westerns, which he loved and had studied carefully. The story unfolds almost entirely on a traditional Western T-set, representing a town with a main street that ends at a cross street. It's a Japanese town from around 1860, not an American one on the frontier in the same era, but its look and feel are familiar from any number of American Westerns.

The climactic showdown between the chief adversaries in Yojimbo deliberately evokes the traditional showdown in the street between gunslingers in a Western, and Kurosawa even introduces a pistol into the confrontation, to make the association, and the irony, clearer.

The film is basically a comedy, or satire, with interludes of action and dramatic seriousness. Its mixed tone resembles to a degree that of Rio Bravo, which had come out a few years earlier and done terrific box office. Yojimbo's comedy, though, is much less genial than the comedy of Hawks's great Western. It has a dark and savage quality, and its fooling with its genre has a edge of malice, a deconstructive quality, as though it wanted to sweep the traditional samurai film into history. Hawks's joshing with the Western genre is loving by comparison.

It was the sardonic edge, the dark comedy, the self-conscious and almost sarcastic attitude towards genre, that defined the Spaghetti Western of Sergio Leone, and Leone took all those qualities directly from Kurosawa's film.

Yojimbo was one of its director's most successful and influential films but not, I think, one of his great ones. The twists and turns of the plot become repetitive, the visual style is too often merely mannered, the sardonic attitude is superficial, almost adolescent in its knowing diffidence. Mifune's wonderful performance ties it all together as an entertainment, at least on a first viewing, but I think the film is more important as a catalyst in the development of the Sixties Western than as an artistic achievement in its own right.

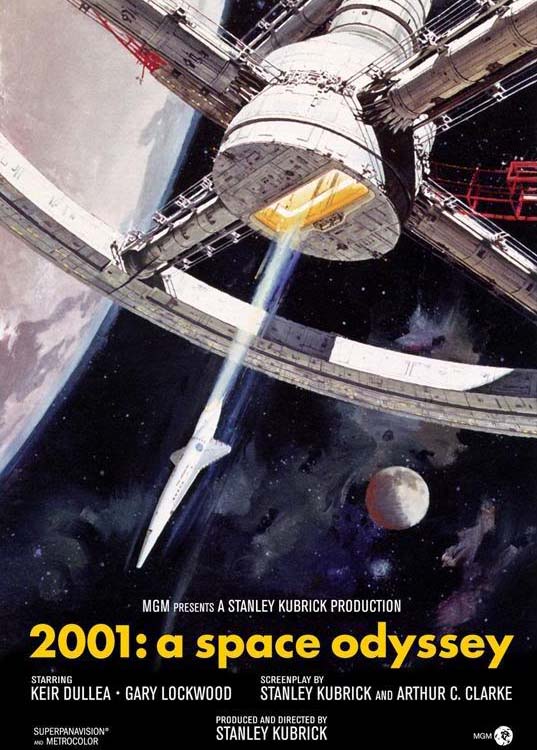

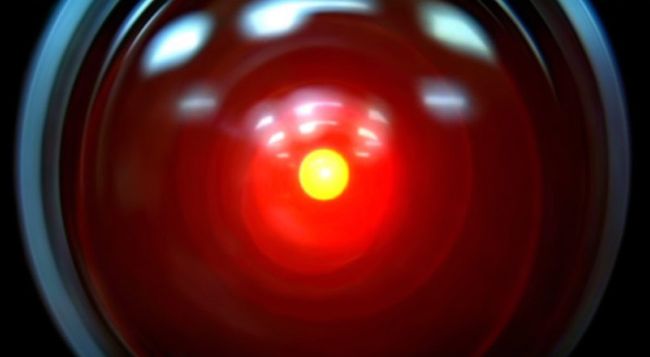

The dramatic narrative of Stanley Kubrick's legendary space epic is meager, to say the least. Crisply told, it could fit easily into a half-hour episode of The Twilight Zone. Its core is a duel to the death between two somewhat mechanical human astronauts and an all too human computer on a mysterious mission to Jupiter. The first 54 minutes of the film are, in story terms, pure exposition, which might have been delivered in a few minutes. The last 25 minutes pay off the Jupiter mission, but not in narrative terms — the climax of the “odyssey”, and the discoveries that prompted it, remain mysterious, unexplained. There is no dramatic denouement.

Half the film is thus in essence about something other than drama, other than narrative. It's about situating us imaginatively in time and space. The first 20 minutes of the film take place in prehistoric times, and illustrate man's discovery of tools — which he turns instantly into weapons. The boldest jump cut in all of cinema takes us from a prehistoric weapon spinning in the air to a space ship circling the earth to the strains of a Viennese waltz. The suggestion is that all human achievement in the interim has been of a piece. Man the maker has used his toolmaking skills to create art and technology, but these are merely elaborations of a single phenomenon.

Indeed, it turns out that the most advanced technology in the film, the HAL 9000 computer that controls every function of the space ship heading towards Jupiter, is also a weapon, a killing machine — an attribute that seems intrinsic to its nature as a tool. It cannot help but incarnate the murderous instincts of the species that made it. When Dave the human astronaut defeats and lobotomizes the computer, it's easy to see this as a kind of metaphorical rejection of technology itself, linked as it is to mankind's murderous proclivities.

Having made this leap, Dave is taken on a mystical journey of rebirth, which presumably will mark a new stage in mankind's development, one as portentous as the one marked by the original discovery of tools.

Both of these turning points of development are accompanied by the appearance of a black monolith, a token it would seem of some higher life form which is prompting man along in his evolution. The monolith is something of a red herring, however. It is never explained, the life form it represents is never shown. It thus becomes merely a suggestive emblem of evolution, or perhaps an admission that the agency of evolution cannot be explained.

What the film is really doing is, as I say, situating us in time, asking us to be aware of our place in time, in a particular stage of human development. The prehistoric era is distant enough that the discovery of toolmaking seems somewhat fantastic, just as the year 2001 was distant enough from 1968, when the film came out, to make the imminent ramifications of technology seem fantastic. But we recognize all too well the violent nature of early man, just as we recognize all too well the bland efficiency of the corporate man of 1968, projected slightly into the future.

What makes the film a film, in the end, instead of an illustrated lecture on philosophy, is the way Kubrick situates us in its imagined spaces — on the African savannahs where early man emerged, on vehicles commuting to the moon, on the moon itself, on a craft penetrating deeper into space . . . even projecting us, at the end, into the unimaginable future.

The meticulous, slow-paced exposition of the film's first hour doesn't read as exposition — it allows us to experience viscerally a routine trip to the moon. The deliberate pace of the duel on the space ship traveling to Jupiter puts us aboard that ship and makes it an environment we can imagine inhabiting. The mind-bending visuals at the end allow us to feel, if not understand, what confronting a new stage of consciousness might be like.

Kubrick is using the full resources of cinema in the service of his philosophical meditation on the state of human development. The red-herring mystery of the monolith, the dramatic suspense of the duel with the computer, supply just enough of conventional movie narrative to string us along on what is essentially an intellectual journey.

Kubrick's intellectual meditation will seem trite if reduced to words alone, but Kubrick puts us into spaces, into seductive environments, in which we ourselves can meditate, internalize for a time the truths Kubrick wants us to entertain, evaluate their resonance within our own imaginations.

In the 1960s, only Godard was making films as radical, conceptually, as 2001. It remains astonishing that 2001 was financed by a major Hollywood studio. Ironically, it was only the resources of a major studio that made Kubrick's conceptual experiment possible, by giving him the money it took to make his imaginary spaces plausible. If they had not been plausible, the film would have been the most boring and superficial slide lecture in the history of movies, instead of what it is — a singular experiment in cinema that still points the way to uncharted possibilities for the medium.

. . . directed and animated by Kendra Elliott — an amazing piece of work.

Check it out here:

“Twilight Lovebite” by Lavalier