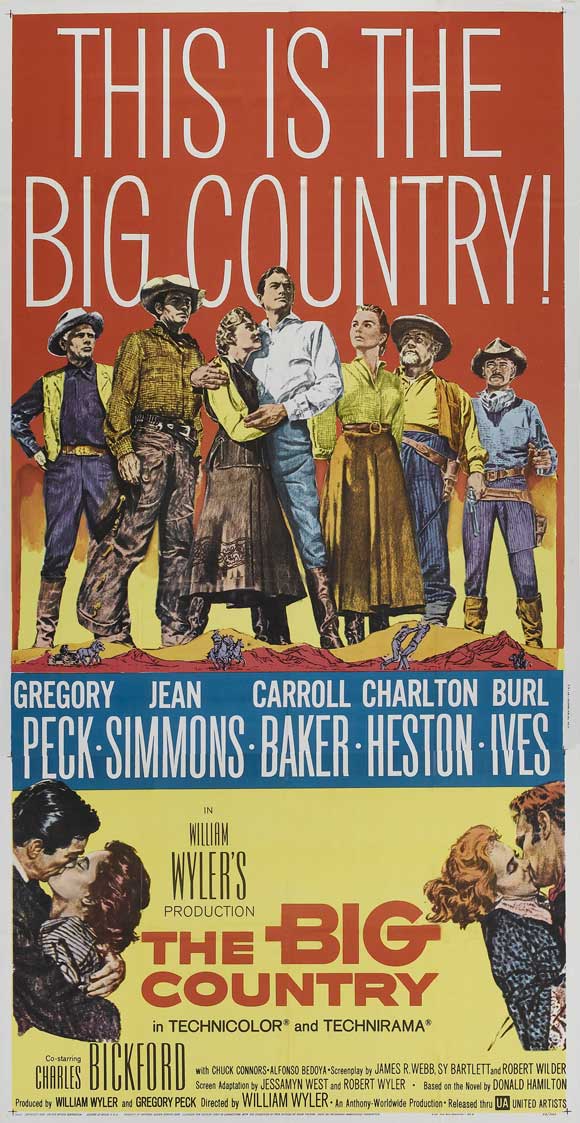

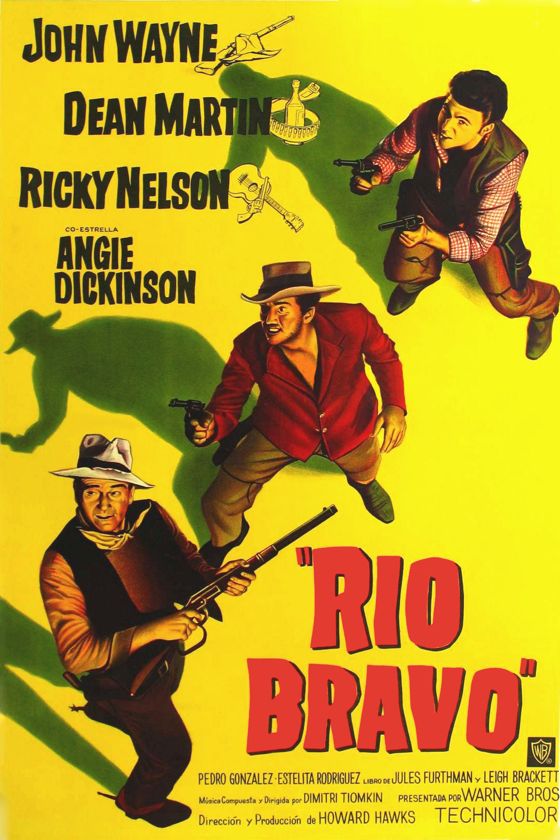

Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo, from 1959, is many people's favorite Western, and there has certainly never been one that's more entertaining. Hawks famously said that it was his answer to High Noon, which he found irritating because its hero sheriff ran around begging the citizens of his town to help him with his job. Sheriff John T. Chance in Rio Bravo, played by John Wayne, pointedly refuses help from the citizens of his town on the grounds that they're not professionals and would only get in his way. (He already has two allies — professional but flawed, just to make things more interesting — and picks up a third along the way.)

This dialectic is a little silly — there are obviously situations in which each approach would be appropriate — but Chance's is a lot more appealing, because it's closer to the classic Western idea of the hero. High Noon is about a town trying (and failing) to make the transition from frontier outpost to civilized community. Rio Bravo is governed by a different vision of the West, in which community in that sense is irrelevant — individual initiative and responsibility are the central and decisive issues.

Chance's attitude also reflects a recurring theme in Hawks's work — a celebration of professionalism, of people who know how to get the job done and do get it done, however cynical they may be about the job itself. The small, closely-knit team, dedicated to a particular objective, is important to Hawks, along with the mechanics of teamwork — society as a whole doesn't concern him all that much, and is often presented as indifferent or corrupt, as it is for the most part in Rio Bravo.

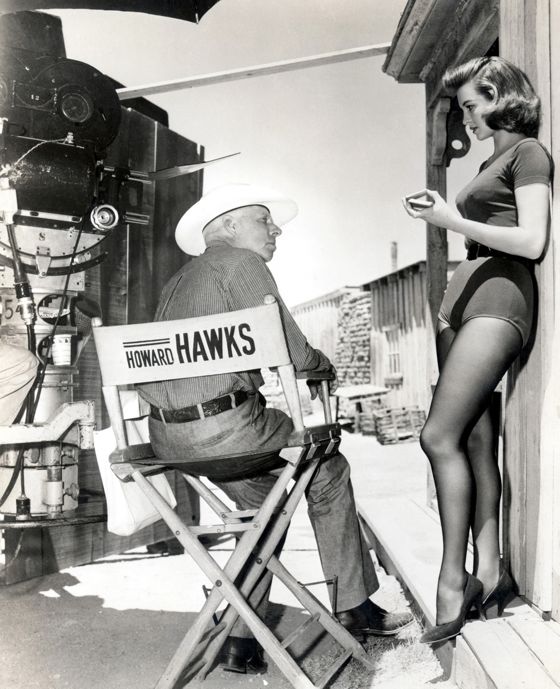

Sex in Hawks's work is also more a matter of teamwork than romance — a game for two that has to be played well, and with a certain amount of diffidence. Hawks's typical women aggressively pursue men they're attracted to, but expect to be amused in return. Angie Dickinson is the hard-boiled dame “Feathers” who pursues Chance in Rio Bravo, asking nothing more than his engagement and encouragement for as long as things last. She's a virtual reprise of the Lauren Bacall character in To Have and Have Not, a drifter and adventurer who's intrigued enough by the hero to pause for a while in her wanderings to play with him.

Feathers initiates the first kiss in Rio Bravo, which Chance responds to almost passively. Then they kiss again and he's more active, at which she pronounces herself satisfied — “It's better when two people do it.” It's a direct echo of Bacall's famous line in To Have and Have Not in which she tells Bogart that kissing is “better when you help”.

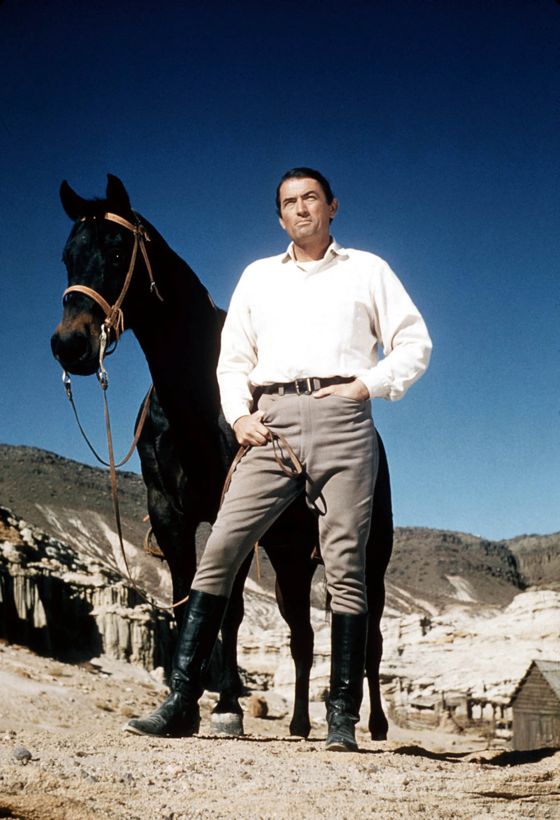

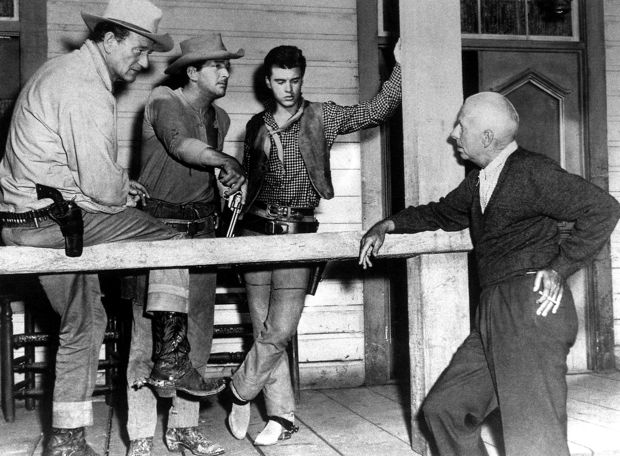

Dean Martin gives a surprisingly strong performance as Dude, a broken-down deputy who has to rehabilitate himself in order to help his friend Chance. Ricky Nelson plays a hot-shot kid gunslinger whose professionalism impresses Chance and leads them into an inevitable alliance.

Nelson's performance is lackluster — he's in the film for marketing purposes — but Hawks uses Wayne's authority as a star and Western icon to lend Nelson's character “Colorado” substance. If John Wayne approves of the kid and takes him seriously, who are we to second-guess him? Colorado has a moment of fancy gun-play in a shootout, but his heroism doesn't really register until Wayne tells the other guys how good Colorado was.

Nelson's presence, and the cheerful tone of the film, let us know that nothing much more than entertainment is at stake in the tale. John Ford is always interested in exposing the moral contradictions of his heroes, in examining the moral landscape of America itself. Hawks is just interested in hanging out with some cool people and watching them do their thing. Rio Bravo unfolds at a leisurely pace but is never dull for a moment — because the company is so good. The only real suspense lies in wondering if the characters will be cool enough when their big moments arrive. Of course they always are — and then some.

The spirit of fun that infuses the film is almost tongue-in-cheek — one can see in it a foreshadowing of the Sergio Leone approach to the Western, in which every Western cliché seems to have quotation marks around it, seems to be delivered with a wink. Unlike Leone, though, Hawks is never interested in subverting or upending the clichés — just in having some fun with them, in the most efficient and elegant way possible.

Molly Haskell has called Rio Bravo “a movie one loves and returns to as to an old friend” — and that's not faint praise for a film which lasts well over two hours and proceeds, as I've said, at such a leisurely pace. It's a “town Western”, too, one that never strays from the town it's set in, that takes place mostly in interiors and on one street on a studio lot. But Hawks explores this narrow geography thoroughly, makes us feel at home in it, and his cinematographer Russell Harlan lights it warmly. The film makes us cozy and comfortable, gives us time to know and savor the quirks and qualities of its characters.

This may make it seem like a simple film, but it's hardly that — the skill required to make something this “simple” so consistently fascinating and enjoyable is hard to value or praise too highly. It takes the kind of cool and impeccable professionalism that Hawks admires and celebrates so agreeably in his protagonists.