The horror. The horror.

The horror. The horror.

Bucking Broadway, a John Ford silent Western from 1917, is included as an extra on the new Criterion DVD edition of Stagecoach. It's a real revelation.

One of the earliest films Ford directed, it has a rather lame plot. A cowboy in Wyoming loses his girl to a visiting Easterner, who takes her back to New York to marry her. The girl has second thoughts about the guy and sends for the cowboy, who shows up in New York with some of his cowboy pals to rescue her and thrash the Easterner, who turns out to be a drunk, a lout and a creep.

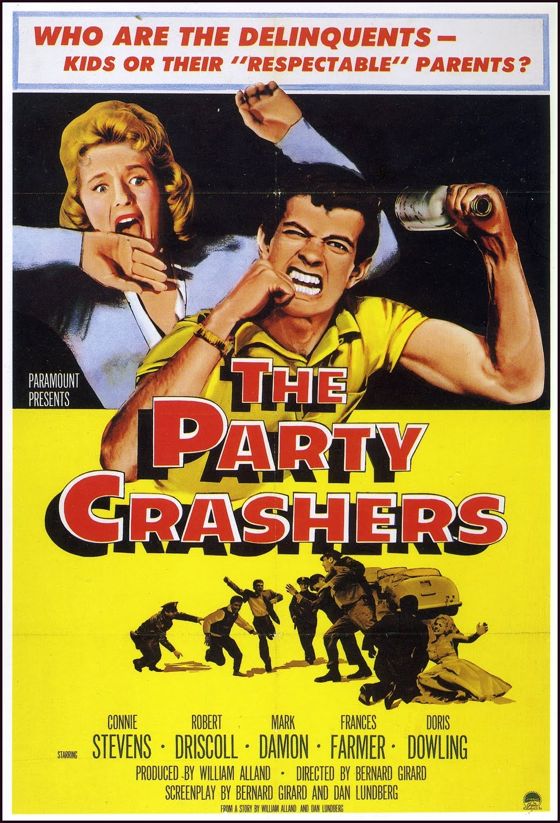

The New York sequences were shot in Los Angeles, so Ford doesn't get to have much fun visually with the idea of cowboys on Broadway. Most of the city action takes place in a big hotel, and the donnybrook between the cowboys and the swells at a big society party there is clumsily staged and unsatisfying. There are a few iconic shots of the cowboys riding horses down the middle of a city street, but there's no more action than this in the urban exteriors.

It's the first half of the film, before the scene switches to the city, that offers the revelation. It's made up of a series of stunningly beautiful images of ranch life, dynamically composed shots that have real poetic power. Even back then, when Ford was just getting started, he had an eye for cinematic composition, for the choreography of movement within a frame that rivaled Griffith's. One could even make a case that his eye surpassed Griffith's by then, just a year after the master directed Intolerance.

Certainly the first half of Bucking Broadway is one of the great achievements of silent cinema, visually speaking. It transforms a simpleminded tale into a lyric poem about the West as lovely as any passage in any film Ford ever made.

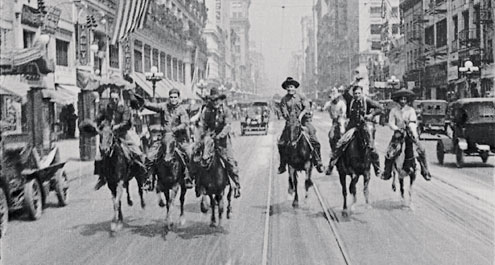

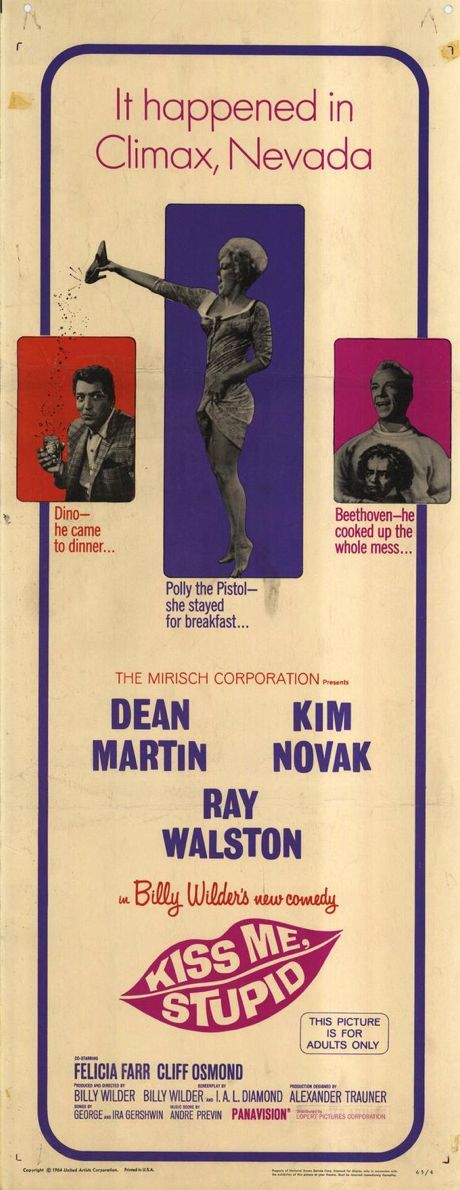

Prompted by Tom Sutpen's insightful thoughts about Kiss Me, Stupid, posted at Illusion Travels By Streetcar, I finally watched this 1964 film by Billy Wilder. Posing as a sex farce, the movie is actually a poisoned-pen letter to the American male — full of bitterness and bile.

As Tom pointed out, Wilder's great sex comedies, like The Apartment, poke fun at the puerile obsessions of American males, but also offer humane female characters who forgive them and to a degree redeem them. The dynamic is at work in Wilder's darker dramas, too, like Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard, but the women don't forgive in those films and the men are not redeemed — they are simply released by death.

There is bitterness and bile directed towards weak, collapsed males in all these films — it's just a question of what, if anything, balances the equation.

Kiss Me, Stupid is unique in that the equation is hardly balanced at all, and in only the most perfunctory way — and yet it is, nominally, a comedy. “Kiss Me, Stupid” might serve as the title for most Wilder films about collapsed males. Its frankness as the actual title of this one seems to reflect Wilder's inability to restrain his contempt for the modern male to any degree at all.

The film opens with a nightclub performance in Las Vegas by “Dino”, played by Dean Martin, parodying — or incarnating, depending on your point of view — his stage persona as a horny, alcoholic hipster. He delivers some patter about the showgirls in the act — cheap sexual innuendo masquerading as humor. The waiters looking on laugh like jackasses at the prurient jokes — the exaggeration of their stupidity is disturbing, totally undercutting the “glamor” of the show and the venue.

It's a kind of set-up for the rest of the film — suggesting that anyone who finds it funny is an imbecile. Wilder has moved from despising the American male to despising his audience. It's a radical act — perhaps not entirely conscious. Kiss Me, Stupid is a film that seems to be powered on some level by a hatred that's gotten out of control.

The women in the film are decent, sensible human beings — like Miss Kubelick in The Apartment. They offer a running commentary on the brutish imbecility of the men. But for once Wilder doesn't give us any avenue leading towards sympathy with the men. “Dino” remains a cartoon boor. The doltish protagonist is played by Ray Walston, who lacks the charm of a Lemmon or a Ewell, which took the edge off of their stupidity in The Apartment and The Seven Year Itch, respectively.

Kiss Me, Stupid ends with the Walston character “humanized” by his encounter with a good-hearted prostitute called Polly the Pistol, played by Kim Novak, but the change isn't convincing — it plays like a sop to audience expectations that comes too late, unfelt and under-dramatized. You sort of hate his wife for settling for a dimwit like him, even if she's found a way to manipulate him into being an acceptable mate.

The film is commonly regarded as an unpleasant failure, but it fails only because Wilder didn't follow his venomous vision to its uttermost ends. But how could he — at least in what purported to be a mainstream comedy? You get a feeling in Double Indemnity that Wilder truly hates his lead couple — not for their criminality but for their bad taste, cheap banter, infantile desires. In a drama, he could resolve this hatred by killing them. In the “comic” world of Kiss Me, Stupid he has to leave his dumb males in their nihilistic hell. The barely perceptible glimmer of hope, of redemption, he felt compelled to offer them reads as a confession of artistic bafflement by Wilder.

You can't kill off every collapsed male in America, after all — but for most of Kiss Me, Stupid you get a feeling that's just what Wilder wishes he could do. He settled for humiliating and degrading them, and in the process humiliating and degrading anyone who might find their predicament amusing.

Kiss Me, Stupid is, finally, an ugly film about ugly men. Some fun, huh? Well, not exactly — but damned interesting, if only as an example of what can happen when an artist is unhinged, deranged by the very passions that, controlled and balanced, fueled his best work.

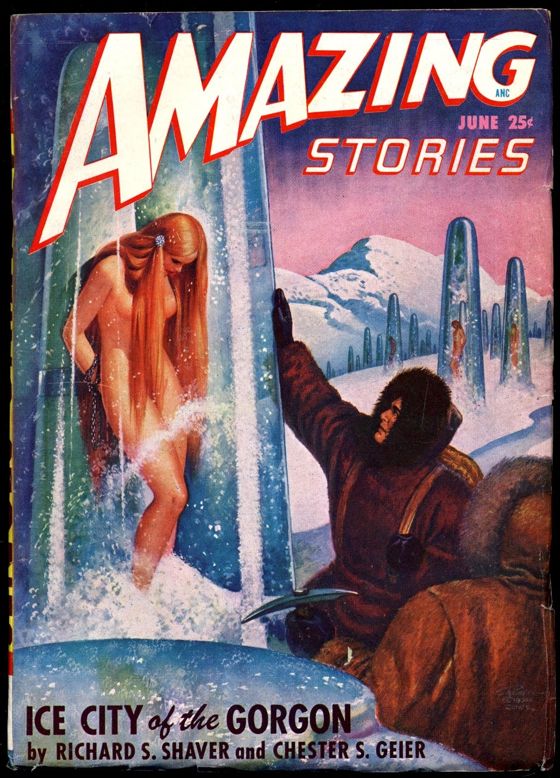

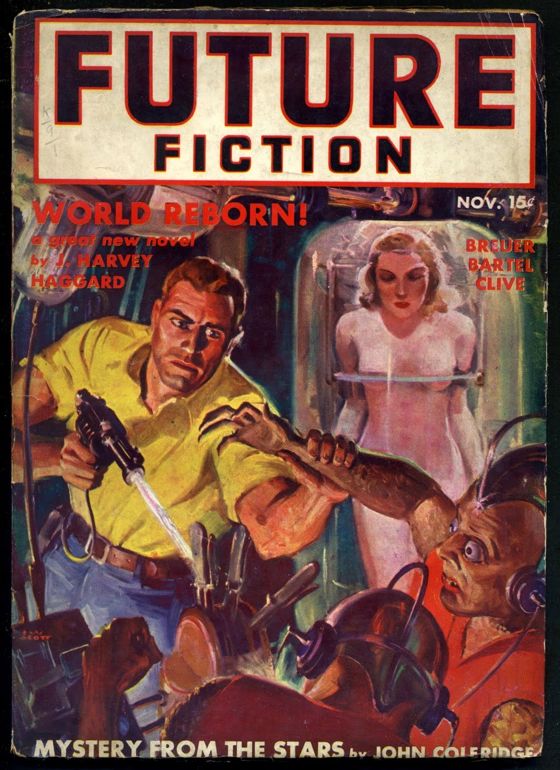

Images of women suspended vertically in transparent capsules captured the imaginations of fantasy writers in the 20th Century. Above and below, illustrations for the covers of pulp science fiction magazines.

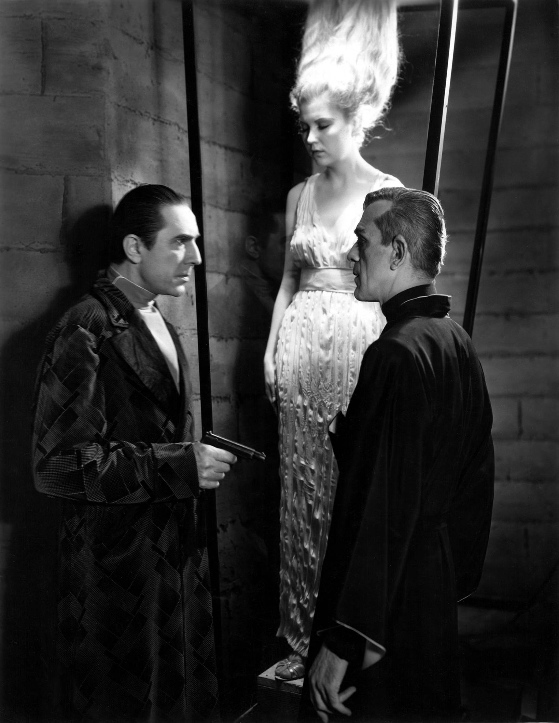

And here's the same idea in a classic Hollywood horror film, The Black Cat:

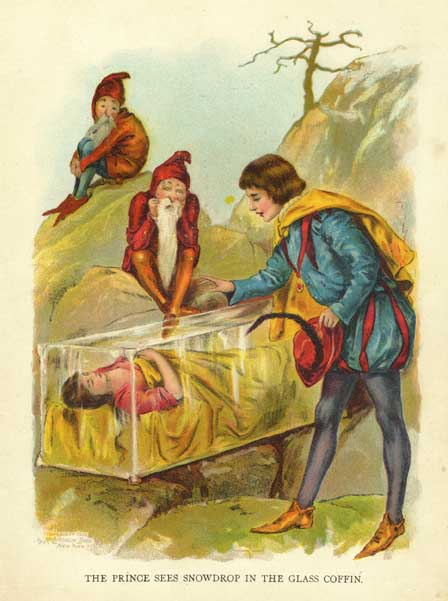

I guess it's just a variant of the glass coffin in which many a fairytale princess has slept her enchanted sleep:

Originally, I suppose, the image suggested a virginal state, from which the prince's kiss would awaken the maid, a kind of sexual initiation. I'm not sure what it signifies in the modern age, but probably not that — more likely a vision of woman as pure image or possession, safe, contained, unthreatening . . .

Imagine cinema as the sea. Imagine being picked up and hurled bodily

into that sea. Some films are like that. Suddenly, you no longer have

a picturesque ocean view, or a pleasant medium for transporting you on

a vessel from here to there. You are wet from head to toe, you are

part of the ocean, and you must swim or sink.

Greed is a film like that. The Last Laugh is a film like that.

Here are some others — Intolerance, Touch Of Evil, The

Conformist, The Searchers, Chimes At Midnight, The Rules Of the

Game, L’Atalante, Titanic, Vertigo, Seven Samurai, Sherlock, Jr., The

Band Wagon. These are not films you can just look at — you

have to navigate them, exert yourself to keep your head above

the surface of them.

I’m not talking about films which merely overwhelm the senses or the emotions (and certainly not the intellect), but films so alive with cinematic, that is to say plastic, invention that you find yourself ravished by the medium itself — aesthetically overwhelmed, as it were.

It doesn’t really matter what you think of such films, just as your opinion of the ocean is irrelevant when you’re thrown into it. You are forced to react to it, on its own terms, not yours, one way or the other. You accept those terms or you drown.

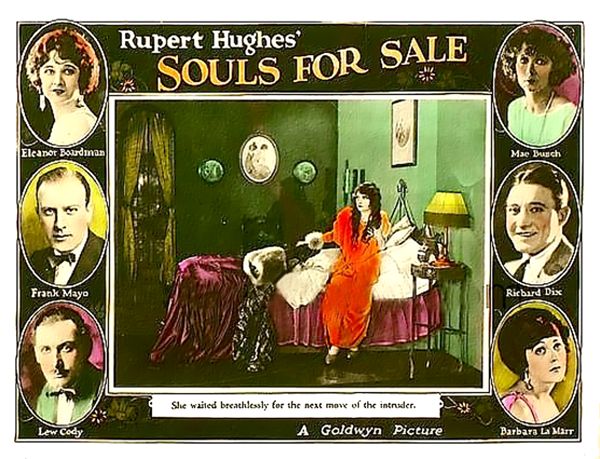

Souls For Sale is, I think, the second best movie ever made about Hollywood, and makes a perfect pendant to the best, Sunset Boulevard. Souls For Sale is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of Eden, just as Sunset Boulevard is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of purgatory.

The sheer, delirious joy of movie-making before the studio bean-counters took full control of the industry is present in Souls For Sale. The film tries to present a balanced view of Hollywood from the other side of the camera, but it can't really — it's too swept up in the nuttiness and energy and attractiveness of the movie folk.

The film features a lot of cameo appearances by real Hollywood stars and directors of the time. One of them is especially poignant. We get a glimpse of Erich Von Stroheim at work on a set for Greed. We know now that he was creating one of the greatest works in the history of American art, but the cameo was filmed when the production still belonged to Sam Goldwyn's company. Before Greed was completed, that company was sold to Metro and the production thus came under the control of Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, who, in an act of unspeakable thuggishness, decided to mutilate Von Stroheim's masterpiece, to send a message to the rest of Hollywood's talent — you are no longer in control here . . . the industry you built now belongs to thugs like us.

In Souls For Sale you can see what was lost in that transfer of power — the giddy excitement of a new art form still in the hands of the artists who created it — just as in Sunset Boulevard you can see the rot and decay of that erstwhile Eden under the influence of the thugs. It's no accident that Louis B. Mayer was outraged by Sunset Boulevard. It was an epitaph for everything he personally destroyed.

The giddiness of that time before the thugs took control informs every moment of Souls For Sale. It's a thoroughly self-reflexive work of art, which pretends to examine how the dream world of the movies is constructed while itself infected with the very dreams it pretends to examine. This tension in its point of view is quite deliberate and often played for laughs, though it more often results in a kind of surreal poetry.

The story opens on a train racing through the desert on its way to Los Angeles. A young bride on her wedding night has suddenly become revulsed by the man she's married and jumps off the train at a remote watering station. She wanders hopelessly through the desert until she comes upon . . . an Arab sheik on a camel, who rescues her from death. He's an actor on location with a film crew, making a movie.

So we have moved with the mad logic of a dream from melodrama to costume drama to comedy. The whole film navigates a similar dream landscape — it's a hall of mirrors from which we never emerge. At the climax, an intertitle informs us that a real hurricane is threatening to wreck the artificial storm set up for the climax of the film within the film — and we proceed to watch the “real” artificial storm ruin the “fake” artificial storm.

If Jorge Luis Borges had ever made a movie, I suspect it would bear an uncanny resemblance to Souls For Sale.

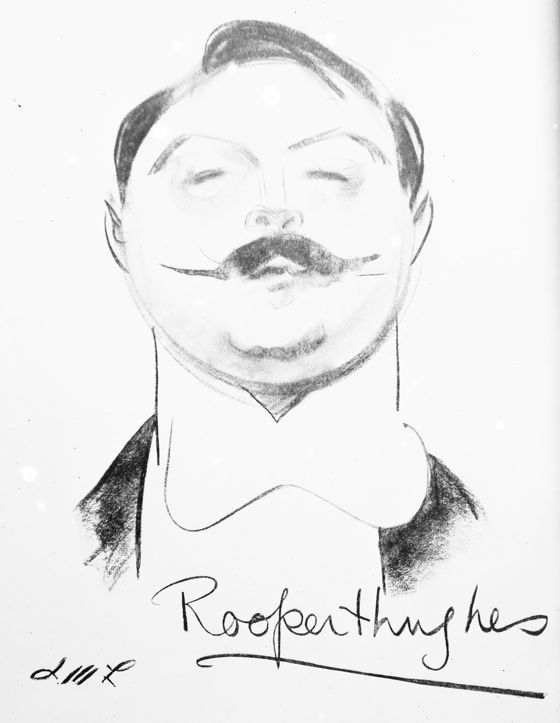

The film was based on a novel by Rupert Hughes and also directed by Hughes (who was Howard Hughes's uncle.) He was a successful playwright, novelist and historian who directed seven films between 1922 and 1924 — then went back to writing. Souls For Sale is a handsomely mounted and photographed production, with fine performances, and it has a few images of real grace and power. Hughes was either exceptionally well-supported by Goldwyn's studio technicians or else he had a genuine gift for directing. In either case, it would be interesting to know why he abandoned the craft.

He left us a minor masterpiece, though — a vision of what the movies might have been without “boy geniuses” like Irving Thalberg and “benevolent patriarchs” like Louis B. Mayer.

This takes existential nullity, a speciality of the exploitation movie, about as far as it can go.

[Be warned — from this point on in my tableau-by-tableau march through Godard's Vivre Sa Vie there are spoilers which might affect your enjoyment of the film if you haven't seen it.]

The film's fifth tableau is titled “The boulevards — The first man — The room”. It begins with shots, from a moving vehicle and on tracks, of streets where prostitutes are plying their trade. Nana, walking along one of these streets, is approached by a man who asks if she's available. She says yes and takes him to a cheap hotel room.

She closes the curtains of the first-floor room, which looks out onto the street, and prepares to have sex with the man. Nana has committed herself to a life of prostitution.

The room is shabby but clean. The man is not unattractive and behaves well at first, giving Nana more money than they've agreed on because she doesn't have change for his 5000-franc note.

But then, when he embraces her, he tries to kiss her, and she resists this, withholding the one intimacy prostitutes traditionally refuse to sell. (This reminds one of Goethe's great line — “The kiss is the ultimate sexual experience.”)

The tableau ends with Nana's struggle against the kiss still in progress. She has been cool and businesslike up to this point — now she looks disgusted and afraid. This dynamic is part of Nana's character as presented in the film. She seems a bit dim, a bit cold about selling herself, but also pathetic. The pathos is all the more powerful for this — she's not a whore with a heart of gold, just a rather ordinary woman of no special distinction, beyond her good looks. She seems incapable of estimating where her path in life will actually lead her, morally and emotionally. This enables us to preserve our pity for her.

Next:

Previously:

The third tableau, or chapter, of Godard's Vivre Sa Vie is primarily about the cinema. It begins with a transitional scene connecting it to the preceding tableau which showed us the protagonist Nana's working life. She returns home but cannot get the key to her apartment from the concierge, because she owes back rent. We know from the preceding tableau that Nana has lent 2000 francs to a co-worker, who wasn't at work that day.

Cast adrift in the city, Nana meets a friend by chance on the street, the guy she was breaking up with in the first tableau, who shows her some pictures of his child, apparently a child he had with Nana. Her only relationship with the child now seems to be through these photographs, through images.

Nana refuses an offer of dinner from her ex because she wants to go to the movies. She goes to see Carl Dreyer's silent film La Passion de Jeanne Arc at the Jeanne d'Arc theater. She's sitting with a date, who has his arm around her, but she is utterly absorbed in the film.

Godard shows us a relatively long passage from the film, cut into his own film — in other words we don't see this passage as images playing on the movie theater screen, which is never shown in the shots inside the theater. Thus, when Godard cuts from Dreyer's extreme close-ups of the suffering Joan about to meet her death to a close-up of Nana reacting emotionally to the images, a kind of equivalence is suggested, on two levels.

Nana is identifying with the character Joan . . . but Anna Karina, playing Nana, is also mirroring or doubling the actress Falconetti, playing Joan. Karina is entering the history of film as an image.

After the film, Nana ditches her date, whom she's apparently just hustled for the admission price to the movie, and goes to meet another man at a café. We've seen Nana “servicing” a male customer at the record shop — now we've seen her trading a little groping for a movie ticket. In the first tableau, her boyfriend accuses her of breaking up with him because he doesn't have enough money — and she doesn't exactly deny it. Godard is establishing the idea of her persona, especially her sexual persona, as a marketable commodity.

Nana and the new guy she meets sit beside each other at the café bar, like Nana and her soon-to-be ex in the first tableau, but they face each other, and we can see their faces. The camera tracks back and forth between them nervously, mostly keeping them in a two-shot but one that's constantly reconfigured.

This nervous, apparently unmotivated tracking makes us conscious of the camera, even as Nana and the man discuss photographs he's going to take of her to help her break into the movies, which is her dream.

The ironies grow elaborate. Godard has already put Karina into the movies, into this movie among others, and suggested an equivalence between her image and some of the most iconic images in all of cinema — but the character Nana is somewhere far behind the actor playing her.

Curiously, this dissonance doesn't disrupt either our sympathy for the character or our delight in Godard's abstract aesthetic gambits. The two levels of meaning play against each other in a logical and beautiful way, like two counterpointed lines in a Bach fugue.

Next:

Previously:

The second tableau or chapter of Godard's Vivre Sa Vie consists of a single very complex shot. It opens on a counter in a record shop where the film's lead character, played by Anna Karina, works. She is servicing a customer, checking to see for him whether the shop has albums by various artists in stock.

At one point she has to move to some bins on a lower level of the shop and the camera pans and tracks with her as she does. In the course of this she chats with two of her co-workers, asking about another employee who's absent from work and who owes her money.

She finds the record the customer wants and returns to the counter as the camera pans and tracks back to the original shot and then tracks along further in the same direction to the cash register, where the transaction is completed by the cashier. The camera tracks and pans back the other way, losing Karina, revealing now a shop window across the street. Continuing to track and pan the camera comes to rest on a view of a busy Paris street seen through the doorway of the record shop.

The whole scene gives us a vivid image of the character's boring work life, her position of deferential service to the customers — a man in this case — as well as a vision of her as someone entirely boxed in by a world of commerce. The camera, panning and tracking, gives us something close to a 360-degree view from her work station, in a single shot. The presence of merchandise and commercial activity wherever the camera looks makes a social statement about the world she inhabits, but the unbroken continuity of the single shot makes us feel it as an oppressive reality.

Next:

Previously:

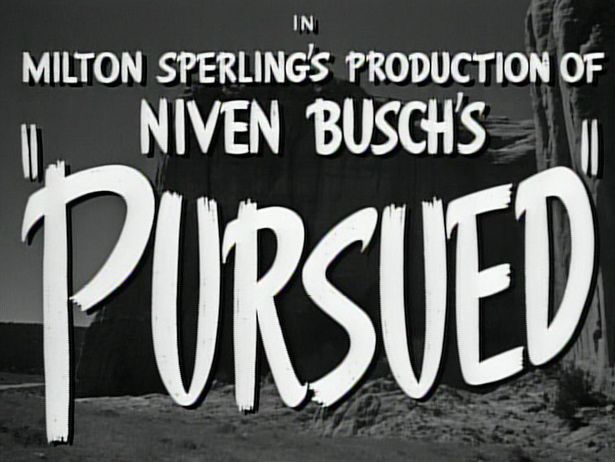

Niven Busch was a crucial figure in the development of the Western after World War Two. He was a New York magazine writer before moving to Hollywood in the 1930s to work as a story editor and screenwriter. He supplied stories or wrote scripts for a variety of genres, including two conventional Westerns, The Westerner, for William Wyler, co-written with Jo Swerling, and Belle Starr, on which he had a co-story credit.

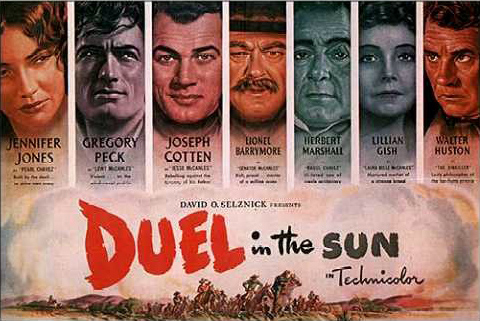

In the early Forties, Busch began writing novels — his second, Duel In the Sun, set in the Old West, was a bestseller and became the basis for David Selznick's notorious film of the same title. This was the film that began to change the nature of the post-WWII Western. Its adult sexuality, which caused it serious problems with the Breen office, its dark Gothic tone and its neurotic or twisted characters marked it as new kind of Western — one more in keeping with the noirish mood of the nation after WWII and Hiroshima.

Busch's own script for Duel In the Sun was discarded, but he was soon at work on an original Western screenplay, Pursued, which many consider the first true noir Western — that is, a Western which deliberately mirrored the themes and forms of the post-war crime thrillers we would eventually call films noirs. Pursued starred Robert Mitchum, who had made a lot of Westerns but was about to become, with Out Of the Past, a true icon of the classic film noir. Busch himself had recently done the screen adaptation of James M. Cain's noirish thriller The Postman Always Rings Twice.

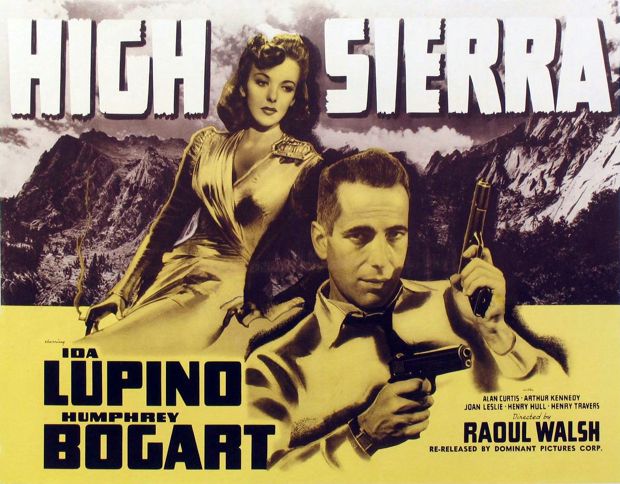

Pursued was directed by veteran Raoul Walsh, who had made some fine pre-war crime thrillers, like High Sierra. These weren't films noirs, exactly, but they were part of one tradition from which film noir emerged (another being the hard-boiled detective thriller.)

Walsh seems to know, though, that in Pursued he's venturing into new territory. Walsh had a spare, no-frills visual style, but the visual style of Pursued is anything but spare. It's dark and moody, almost expressionistic at times. In High Sierra, Walsh's style has a documentary quality — he's looking at a desperate man colliding with a desperate destiny in an almost clinical way. In Pursued he's trying to get inside the psyche of his haunted protagonist.

Pursued is structured as a series of flashbacks, which wasn't a common device for Westerns but became a very common one in the classic film noir. The Western landscape in Pursued is not a symbol of freedom and redemption, as it is in most Westerns. It has an ominous, threatening aspect — like the urban labyrinth of the film noir.

It's almost as though the neurosis and existential anxiety of the urban noir has infected the Western genre — and in truth I think that's pretty much what happened. The atomic-era crime thriller, what we now call the film noir, was a very popular genre, and Duel In the Sun was a big box-office hit. There was commercial calculation as well as artistic daring in the move to darker and more adult Westerns.

However, for all its importance as a milestone in the development of the post-war Western, Pursued is not a very satisfying film. The noirish elements haven't been fully integrated into a consistent tone — as they would be in the later edgy Westerns Anthony Mann made with Jimmy Stewart. Pursued lurches from mood to mood and style to style, sometimes playing like a standard Western, sometimes like a Gothic romance. Busch's attempt to tell a tale of dark destiny feels mostly contrived, without the psychological persuasiveness of The Furies, for example, based on another of his Western novels. Pursued has its moments of perverse power but is more interesting as a stage stop on the way to the genre-bending Western territory that lay ahead.

Commemorating the shortest, saddest, most electrifying love affair in movie history.

In a very interesting comment thread on Facebook, sparked by some remarks in the press by Cotty Chubb about the film Unthinkable which he produced, John Tarnoff raised the issue of “4-wall digital” distribution. “4-wall” is the practice of renting a movie theater to showcase a film which hasn't gotten traditional distribution. It's usually been done in a major city, hoping to get press attention, which then might lead to traditional distribution. It still required expensive local advertising, usually in newspapers, and of course at least one costly photochemical print of the film.

But things have changed. Digital projection doesn't require costly photochemical prints, and online advertising, including peer-to-peer advertising, could theoretically reach enough people to fill a movie theater at any given showtime. The decline in attendance for traditional theatrical films, and the shrinking of their demographic appeal, is likely to continue, even though revenues will continue to flatline, more or less, due to inflated ticket prices (which is what 3D is really all about.)

4-walling suddenly seems like an interesting alternative to traditional distribution, since theater owners still need people marching past their concession stands and since the costs of 4-walling have fallen to within the capacities of independent producers — if they can figure out how to do it right.

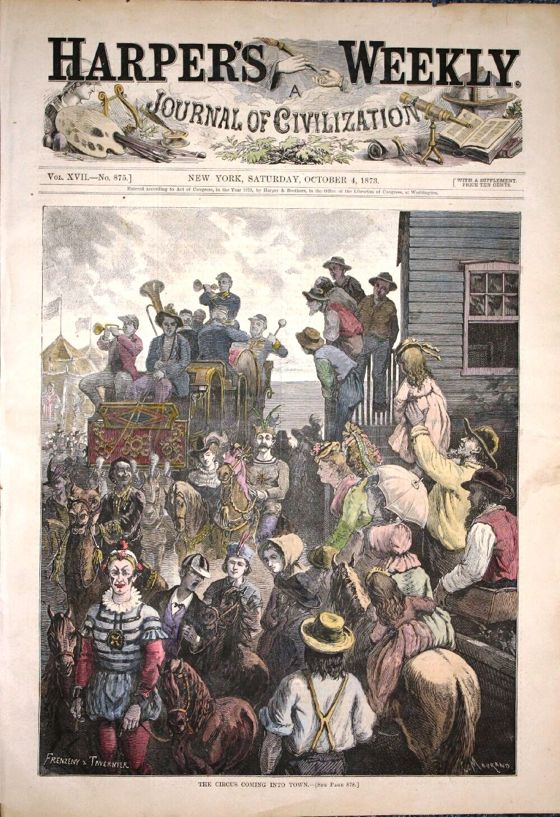

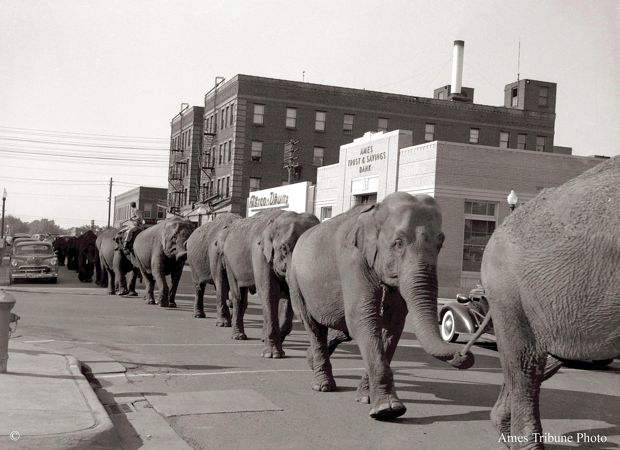

Doing it right is going to involve relearning the ageless techniques of exploitation and ballyhoo. Seeding mentions in discussion groups or on Facebook and Twitter is only part of the equation. 4-wall exhibitors are going to have to make some waves in the local community where the film is to be shown — which was the function of the classic circus parade. The performers of a circus would march through the streets of the town they were about to play, previewing their wares. This was an entertainment in itself, all given for free, to build interest and excitement.

A free concert in a park or shopping mall might be the modern equivalent — or even a parade, done in collaboration with some local group with a connection to the film's subject matter. We're talking about relatively small towns here, places where a little free entertainment is a big event . . . but the train circuses played lots of relatively small towns and made most of their money from them.

We're also talking about films that don't cost too much to make — ones with budgets in the hundreds-of-thousands-of-dollars range, not the millions-of-dollars range. And that means they have to be really, really good films.

The theater experience needs to become an event as well — with the stars of the film in attendance, programs, ushers in character costumes (volunteers from the local high school drama club). And I mean “stars of the film”, not “stars” in the current sense of the word, because such stars won't show up in Cheyenne, Wyoming for a live appearance in a shopping mall or at a rodeo. All the creators of the films of the future will need to think of themselves as part of the traveling circus that the film will become.

The online communities that coalesce around certain films also need flesh-and-blood equivalents — a convenient venue, for example, where people who've just seen a film can assemble to discuss it and to bond. Such assemblies would be mighty engines of the word-of-mouth advertising that any film needs to succeed — and create the core of future audiences for future films from the same artists. These assemblies are also opportunities for merchandising — just like the CD and T-shirt tables at rock concerts.

Theater owners used to cook up ballyhoo like this, with the help of the studios, even back in the days when almost everybody in America went to the movies every week. Now that more and more people are declining to go to the movies, such exploitation has become critical.

Producers of small films need to wake up and take charge. The days are past when you could just feed your movie into the distribution machine (if you were lucky), do a little press in the big media centers, and hope for the best from newspaper reviewers and the audience.

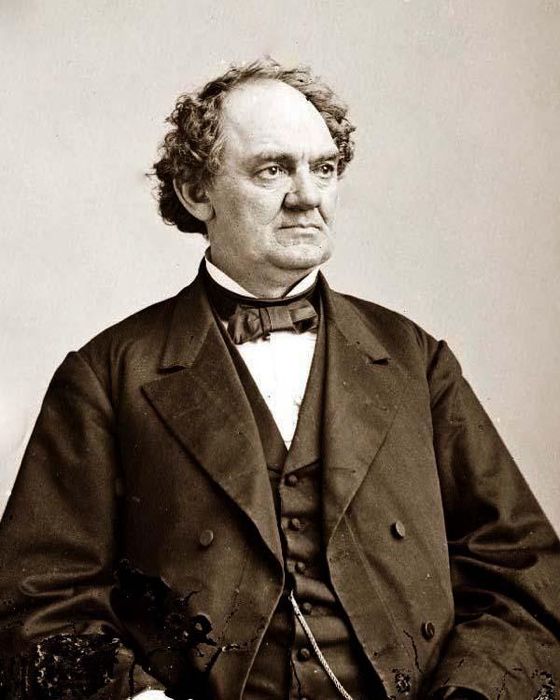

We need to revive the spirit of Barnum (above) — who would do anything, and I mean anything, to drum up interest in his attractions, at his museum or in the rings of his traveling circuses. He realized that ballyhoo is itself an entertainment, an art form — that people love to be bamboozled out of their pocket cash if the bamboozling is daring and spectacular enough . . . and if the first dose of it is free.

Ironically, in this virtual age of ours, the time has come for showmen to get back out on the road — to feed the virtual world with real-life hokum. This is what musicians have come to realize — their money today is made on the road, in live concerts, in providing unique experiences for their fans.

Of course, it will all be meaningless if the attractions, the movies, don't work for people — but that's another advantage of being out on the road. You find out what people want and don't want in the most direct and sometimes brutal ways. They teach you what kind of movies to make — in a way no focus group or demographic analysis ever could, and certainly in a way no studio executive trying to parse the box-office returns in Variety ever could.

To sum it all up as succinctly as possible — modern producers need to start thinking of themselves as showmen again . . . they need to abandon Hollywood, the motion picture capital of greater Los Angeles, and get some sawdust and elephant shit on their shoes.

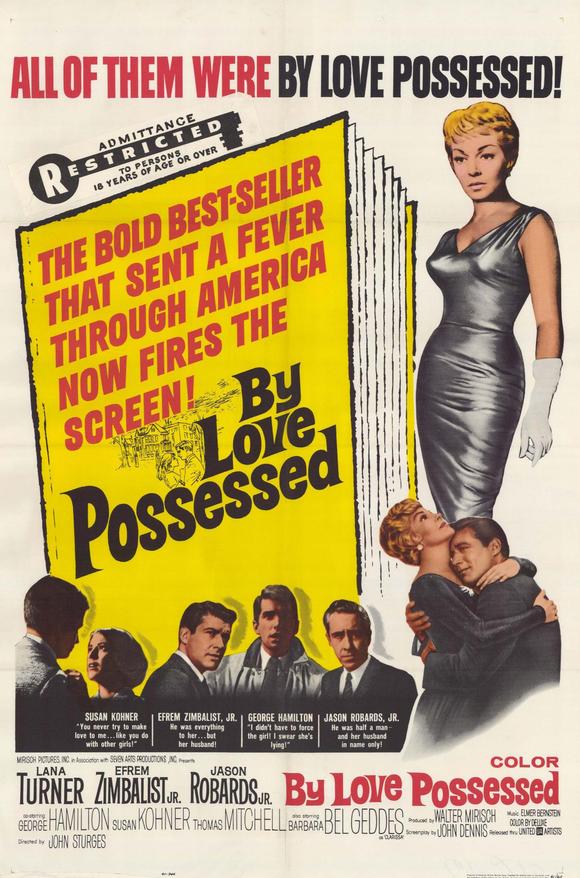

The first part of a remarkable two-part essay by Paul Zahl on the James Gould Cozzens novel By Love Possessed and its screen adaptation by John Sturges.

A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (Part One):

The once extremely popular novel of the year 1957 entitled By Love

Possessed, written by James Gould Cozzens, was made into a Hollywood

movie in 1960 and released the following year. The novel tells the

story of Arthur Winner, Jr., a very sane and prudent attorney living in

a small town in mid-Atlantic America, as his life unravels over a

period of 49 hours. Arthur Winner, who is always referred to in the

novel as “Arthur Winner”, navigates defending a pretty indefensible

young man, for whom Arthur Winner feels personally responsible, from a

charge of rape; as well as helping a legion of citizens of Brocton,

their small town, with their unending personal, legal, and financial

problems. Somewhat priggish — that is what the many hostile critics

of By Love Possessed called Arthur Winner — but also unflappably calm,

Arthur Winner succeeds in holding the wolf of anxiety at the door,

until . . .

Because I hope this post may succeed in making you want to read the

book, I won't give away what becomes of the limits of Arthur Winner's

ability to keep it together.

I will say that the brilliant and wise hero is, credibly, reduced to a

humbled condition, almost a desperate condition. And, partly through

the aid of his friend and law partner Julius Penrose, Arthur Winner

finds the hidden door, the still small voice of an answer, through the

box canyon of his shattering humiliations and disappointments. The

novel's resolution is noble, lyrical, and possibly true . . . to life.

Because By Love Possessed was a number one best-seller for many months

— something close to a national sensation in the fall of 1957 —

it was filmed as an “A” production in 1960 by an independent production company releasing through United Artists. The movie version starred Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. as

Arthur Winner, Jason Robards, Jr. as Julius Penrose, and Lana Turner as

Marjorie Penrose, the extra-marital love interest of the Man of

Reason, Arthur Winner. Other familiar actors played supporting roles,

such as George Hamilton, Thomas Mitchell, Susan Kohner, and Barbara Bel

Geddes. By Love Possessed was directed by John Sturges, who also

directed The Magnificent Seven, released in 1960. John Dennis wrote

the screenplay, which was a big challenge, as the novel is actually an

epic, with many interlocking characters and a lot of talk and a lot of

ideas. The music, which is wonderful in a kind of 1950s soap-opera

manner, was composed by Elmer Bernstein.

I want to say something about movies and books in relation to a comparison of the two versions we have of By Love Possessed.

But first, two additional facts about it:

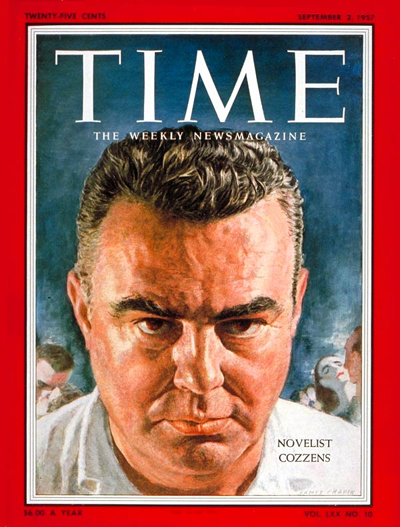

This novel became the object of a famous attack in print by Dwight

MacDonald, in the January 1958 issue of Commentary magazine. Because

Cozzens refused to take the trouble to check the copy for a Time magazine cover story about him and By Love Possessed, several extremely

damaging statements, which he claimed later were not his words at all

but the words of the two hostile writers who interviewed him, had

appeared in print, for the country to see. They made Cozzens sound

like a social snob, who was also bigoted toward African-Americans and

Jews. Although he was a snob — more a “meritocracy”-type snob than a

WASP snob — he was not a racist. His 1949 Pulitzer-Prize winning

novel Guard of Honor had exposed racial segregation in the Air Force,

taking the lid off a subject that many people did not like to talk

about then. Cozzens was also not anti-Semitic. His only real friend,

for he was a hermit in effect, a little like J. D. Salinger in that way,

was his wife. And his wife was Jewish, a well known literary agent in

Manhattan and a liberal Democrat. Nevertheless, certain attitudes of

some of the characters in By Love Possessed are intolerant. So Dwight

MacDonald, stoning the book and its reclusive author, believed he was

taking on “Eisenhower-era” intolerance and complacency.

James Gould Cozzens' career never recovered from MacDonald's attack,

which was widely accepted as being true and accurate. The January 1958

attack on Cozzens was his Nightmare on Elm Street. He had written

incisively and even shatteringly, I believe, about “Ivy League”

characters in a small mid-Atlantic town, a town full of Water Streets,

and Market Streets, and Elm Streets; and then paid a nightmarish price

for it. You can read about the personal effects and “after birth” of

the abuse he took from the critics, in the journals he kept from 1960

to 1964 when he was living in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Oh, and Cozzens was also accused of being anti-Catholic. And

anti-Catholic he was, no doubt about it. Religiously, the writer saw

himself as a “P. E. agnostic” (i.e., Protestant Episcopal agnostic), who

regarded most expressions of Christianity as superstitious.

The second fact I need to mention about the book in relation to the

movie is that the author saw the Hollywood version twice and wrote down

his reactions. This is how James Gould Cozzens reported his first

viewing of By Love Possessed in his journals [VII 19-VII 22 (1961)]:

By Love Possessed was opening at the Capitol [i.e., in New York City]:

and though I thought little of the idea, at loose ends after lunch at

the Harvard Club [above] I followed S.'s [i.e., his wife's] suggestion and went

up. I must admit I got several surprises. For one thing, the

photography was simply and even, sometimes, amazingly, beautiful. For

another, the direction gave constant signs of intelligence, especially

in small touches, often faithfully taken from the book. When law, for

instance, was touched on, the to-be-expected nonsense was carefully not

made of it. The simplification, by sometimes telescoping, sometimes

eliminating characters obviously necessary if the material was to be

got into any actable form, showed evident judgment. Flabbergasted, I

can only say that, taken all in all, I found it a good deal better than

the critics (who probably missed all the good careful small points)

claiming it made a mess of the book, had allowed.

Later, on April 21st, 1962, Cozzens saw the movie again, this time with his wife. Then it was showing in Williamstown:

S. hadn't seen the By Love Possessed film and when it turned up

(second time around) at the Spring St. theatre today insisted on

going. Seeing it a second time, I was again impressed by much really

beautiful photography, and a number of excellences of small detail and

minor casting — the man, whoever he was, cast as “Dr. Shaw” [i.e.,

Everett Sloane] in the trifling part allowed him was almost

disconcerting, he was so exactly in face and manner what I was seeing

as I wrote.

But it was as plain as ever that the job they undertook was impossible:

the book defeated them at every turn and was indeed specifically

intended to. [PZ's Italics.]

A play, an acted entertainment by definition, can't be “honest”

exhibiting True Experience. Actors act “parts”: plays must provide “parts”. The whole basis is “Let's Pretend”. Anything “real” or “true” will destroy or at any rate vitiate this basis. Life is life,

not a play: a play is a play, not life. It seems to follow that an

effective play must cut loose from considerations of: is this probable?

(or even: is this possible?) and proceed on the principle of, say,

Hamlet. Never mind whether this situation makes sense, never mind if

it's obviously impossible. Assume it to be the situation: Now, what

next?

I think this has to be interesting to people who are interested in

movies. Here is a deep and dense novel — even the people who hated it

admired its craft and structure, and its verisimilitude to life as

lived by people like that — which was translated into a lavish

Hollywood production with a famous star and the most costly energies of

studio film-making. And the novel's author, who rarely went to movies

and rarely talked to people or even saw them on the street, approved

of the full treatment.

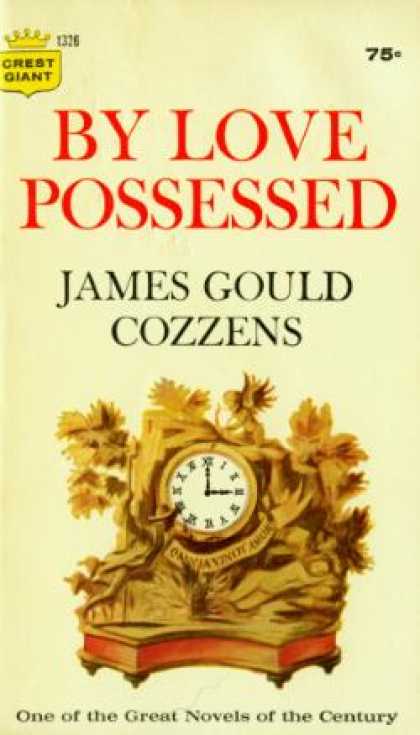

Now, with the book in one hand — my wife's family owned a

first-edition with its famous cover of the “Omnia vincit amor” clock [the paperback edition, with the same cover design, is pictured above] —

and a videotape of the movie in the other (“Miss Turner is as fine as a

red hot flame!”), I would like to compare the two, looking for

similarities and disparities. Since I love the book, admiring

absolutely its reportorial and philosophical ambition, I feel a little

vulnerable. But here goes . . .

Click on the link below for the second part of this essay:

Part two of Paul Zahl's essay on the novel By Love Possessed and its screen adaptation:

A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (Part Two)

Arthur Winner's “nightmare on Elm Street” begins when a Roman Catholic

lady friend of Marjorie Penrose attempts to convert him to the true

church in the setting of a rose garden that bears remorseful memories of his

affair with Marjorie, the wife of his law partner. This Mrs. Pratt

corners Arthur Winner and very skillfully, and craftily, turns the

conversation in the direction of his past sins, which Marjorie has

apparently confessed to her. Just when the Man of Reason thinks he is,

as usual, in quiet control of things, Mrs. Pratt harpoons him. She spears him straight to the heart: “Thou art the man”. Arthur

Winner is only saved from complete humiliation by the appearance, in

the underbrush, of a snake!

From this point on, the humbled hero of By Love Possessed is so fully

de-constructed that he has no choice but to take his famous literary

walk from the steps of Christ Church (Episcopal), where he has been

ushering at the Sunday morning service and where he is to become the

next Senior Warden, over to the crucial Detweiler House, then past the

Courthouse and the Christ Church again, past his law office, past

the Union League Club (moribund and soon to close), past the

storefronts of Main Street and beyond, up the street where the old

families of Brocton used to live, right up to the entrance of the house

in which he was born and where his mother still lives, to make his

great and ever remembered (for those who read the book) entrance,

calling upstairs to his aunt, his mother, and his wife.

This is Arthur's nightmare, a universal dereliction of disillusionment,

by which he must catch at hope in a new way. I, for one, find the last

five pages of By Love Possessed satisfying, real, and ennobling. They

took me by surprise. I think about them every day.

How does the movie version envisage the emotionally overwhelming finish

of the book? The answer is, not very well. As Cozzens himself

remarked, in his journal entry describing his second viewing of the

movie in Williamstown, the script writer had collapsed some characters,

and had to diminish the inwardness of the book. So much of this novel

is inner dialogue, inner qualifyings, inner voices of contradiction,

and association; inner asides, both cruel and kind. Thus the

cascading, baroque language of the book is lost in the movie. Of

course it is lost. The visual image is not the same as the written

word.

In its ambitious attempt to put this complicated story in a narrative

without flashback, into a linear tale which takes you somewhere, the

movie fails. I don't see how anyone would really dissent from that

judgment. By Love Possessed The Movie flattens everything out. It

has only its story to tell, brick by brick, or step by step. No one

has gotten inside the story and then developed it cinematically, either

through the composition or the editing. The building and billowing

mood of the book, and also the philosophy of resignation that the book

embodies: they're not on film.

Only in two sections, so far as I can see, do the director and crew get

under the story, to what it is really about — which is the shipwreck

of love that attempts to possess, the forms of love that try to possess

the loved object. Loving that possesses the lover, and thus is about

the lover rather than the beloved — whether it be the love of a parent

for a child, of a husband for a wife, of a high-school girlfriend for

her selfish boyfriend, of an old patrician man for his reputation in

the town, or, in a case so important to this novel, of a “responsible”

older sister for her feckless younger brother — possessive love makes

catastrophes of human relationships. The book is about the victory, in

utter failure, of a man who overcomes the possessiveness of love in

order to, well, live, and then, counter-intuitively, love. That man is

Arthur Winner. What Arthur Winner stumbles on, you might say, is the

victory of resignation, the acquiescence of defeat which results in a

simple solution of simply taking the next step in good faith.

Only in two sections of By Love Possessed The Movie is the deeper

interest of this material expressed visually. There's a lot more

footage outside of these two sections, but it has an almost indifferent

quality of detachment (the wrong kind), which is not philosophical

detachment but rather, “I think we'd better film this thing as quickly

as possible, grin and bear it, and get our product into theaters while

people can still remember reading the book a couple years ago.”

The one section of the film that catches some fire is the scene of

Marjorie Penrose (Lana Turner) coming on strong to Arthur Winner (Efrem

Zimbalist, Jr.) in the Victorian “wedding cake” summer house behind his

home in Roylan, the little enclave just outside Brocton where the

professional families live. This is a memorable scene in the book,

persuasively underlined by thunder and lightning, the last heat of

summer in the autumn leaves, and the very beautiful garden building in

which the conversation takes place. The set dressers here, the sound

effects and music, the roll of the fallen leaves, the effective and

dramatic lighting, and the two performances themselves all come

together to evoke the spirit of the book. I guess there is nothing

particularly cinematic to see, neither in the camera movements nor in

the editing. But the technicolor style, with that swirling music, kind

of takes your breath away. For five minutes. I imagine James Gould

Cozzens was pleased with this scene. The message of the scene( if it

could be put into words?): A nice and ordered Georgian garden with a

decorous Victorian summer house, and it's all about to be ruined, by a

love that possesses its demoniacs.

The second and for my money the only other sequence in By Love

Possessed The Movie that works, is the opening credits. They are very

good. Why very good? Because they capture, in just a few expertly

edited exterior shots and one long pan, the emotional, geographical

context of the story, this story of one man's struggle to find the

answer to the question of how and also why it can be possible to live

in the presence of hope. The camera shows two churches around the town

square, one Episcopal, one “mainstream” Protestant; the Court House;

the Union League Club, dying home to the old and increasingly few first

families of Brocton; and a few old and tired 19th Century mansions

still in use. It feels a little like the main square of Columbus,

Ohio, tho' smaller; or the main square of Columbus, Georgia, about the

same size. Then, at the end of the credits, as “Directed by John

Sturges” flickers on, and off, you see Arthur Winner, briskly but not

hurriedly, calmly but not unconcerned, striding, or rather, simply

walking, across that “Brocton Square”.

The credits for By Love Possessed The Movie capture the atmosphere the

book projects. They are the high point of the film.

“Ain't that peculiar? (Peculiar as can be)”: The story is fully

captured in “second unit” work, with not a word spoken nor any

exposition offered.

There is a lot you could say about this. We have a book that is

possibly great — its controversy never diminished its claim, not

self-made, to gravity. By Love Possessed, I repeat, is a grave and

serious book. We also have a movie version that was probably produced

simply and almost only to capitalize financially on the popular success

of the novel. And so the movie tells its story, the best it can,

having to cut the inwardness of the source, the complexity of the plot,

several important characters, and certainly the religious concerns of

the source. (The Episcopal church in Brocton, together with its young

, well educated, and sincere if inexperienced Rector, The Reverend

Whitmore Trowbridge, S. T. D., figures importantly in By Love Possessed;

and Cozzens's depiction of a Sunday service of Morning Prayer is

absolutely the last word in clinical portraits of what they are

actually like. I know what they are like.) There is nothing

controversial in the movie version — no anti-Catholicism, no “Uncle

Toms”, no intolerant remarks about New York lawyers from the failing,

unsteady patriarch Noah Tuttle, none of that! Only the references to

sex have been kept, but even there, oddly enough, the better sex is in

the book and describes a happily married couple making love.

Here I close. Let me confess something. I love this movie! It's not

very good; it is actually boring; the camera set-ups and pacing are

perfunctory; the actors sleep-walk through their parts, with the

exception of Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., who does convey the vulnerable

actuality of Arthur Winner; and the conclusion is rushed and overly

happy. (The ending of the book is hopeful, but not happy.) Yet I love

this movie.

Why? Because it connects in visual form with some of the constructions

my imagination had made on the basis of the words. The town, the lead

character, the meeting by night in the summer house, the gushing,

oceanic music — these are there, right up in front of you.

If Orson Welles had made this, it would have been a completely

different result. It would not have been the book at all. Or it would

have really been the book. If John Ford had made it . . . well, John Ford never would have made it.

As it is, we have John Sturges's big but little piece of work. Although

I will probably keep the novel with me until the day I die, and though

I make no claims for the turgid tired movie it spun off, I will probably still keep the movie under my pillow, for the next six months.