In a review of Legends Of the Fall, which he called “the Monty Python version of Bonanza“, Terrence Rafferty said that making a cynical Western was the equivalent of shooting someone in the back.

Westerns got very edgy and borderline neurotic in the 1950s but they didn't get cynical until the 1960s, reflecting a deep distrust of American government and a sweeping re-evaluation of American values, centered around the war in Vietnam and made keener by the assassinations of several key progressive political leaders. It seemed like a good idea at the time to question whether or not the American dream had always been a lie.

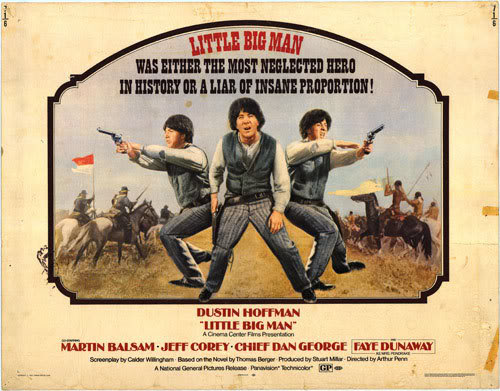

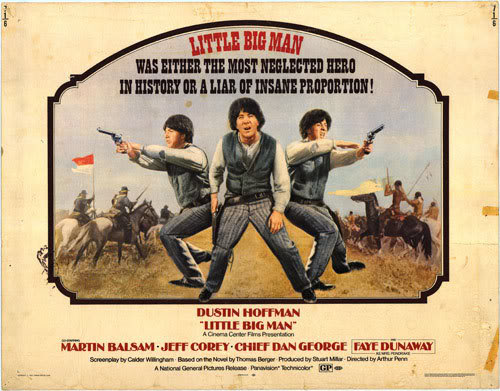

The Western, of course, had always been a genre in which basic American values — self-reliance, common decency, gallantry, justice — were tested and found to be both worthy and enduring. But it was also a genre in which the subjugation of Native Americans was generally celebrated, and obvious parallels could be drawn between that and what we were doing to the Vietnamese people — as they were, for example, in Arthur Penn's Little Big Man. The Western was thus a natural place to start the deconstruction of the American dream.

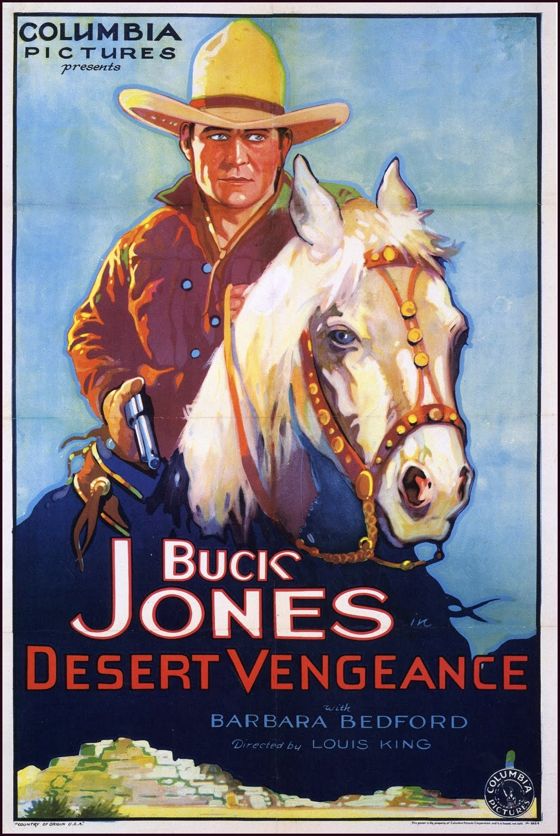

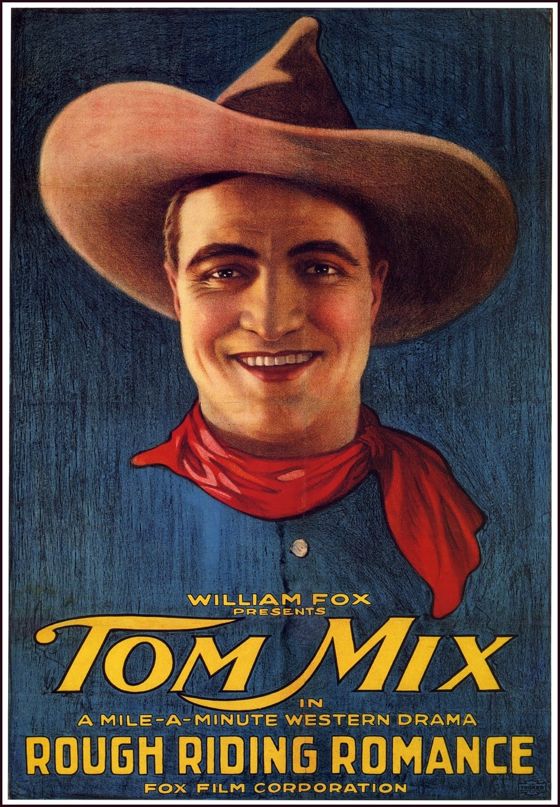

The irony is that by turning the whole myth of the Old West into a lie, American movies lost part of their ability to endorse values which might have aided America in rescuing itself from the perversities of the 60s. Cowboy heroes were, after all, honest, independent and defenders of the weak and the wronged, who often enough in Westerns were exploited and oppressed Native Americans.

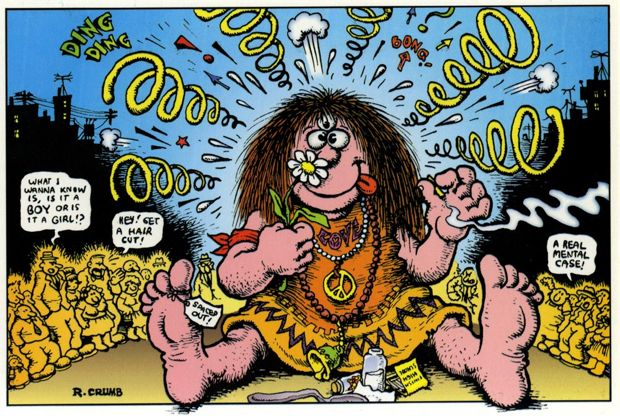

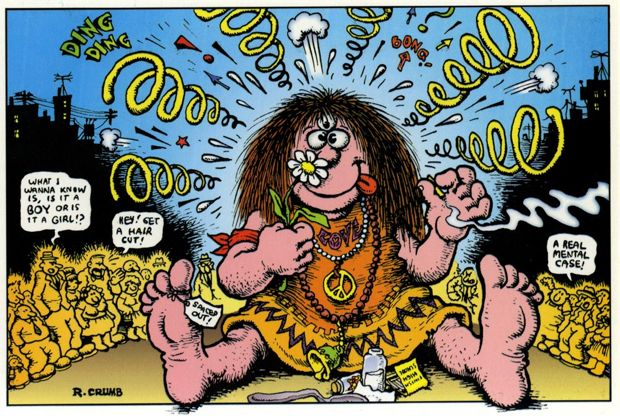

The lost myth of the cowboy hero was not replaced by anything even remotely comparable. The anti-hero, who expressed his bona fides only in opposition to establishment values, was an unreliable guide to moral behavior. The free-spirited hippie was not a creature of action but of solipsistic ecstasy, of sensual indulgence.

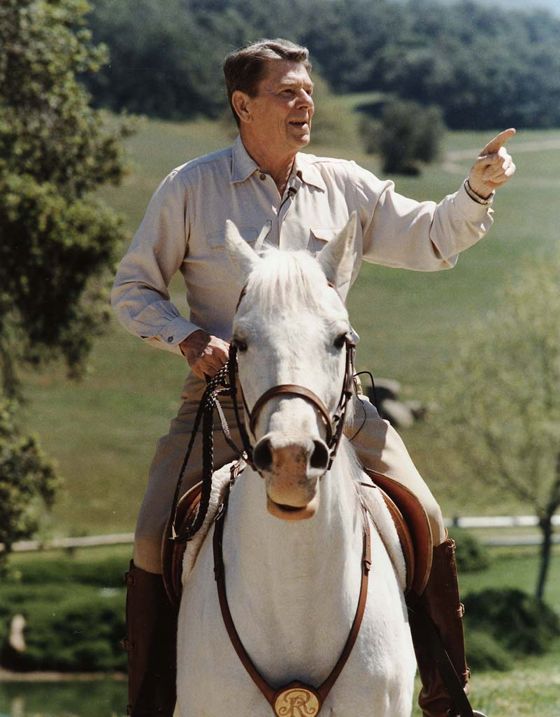

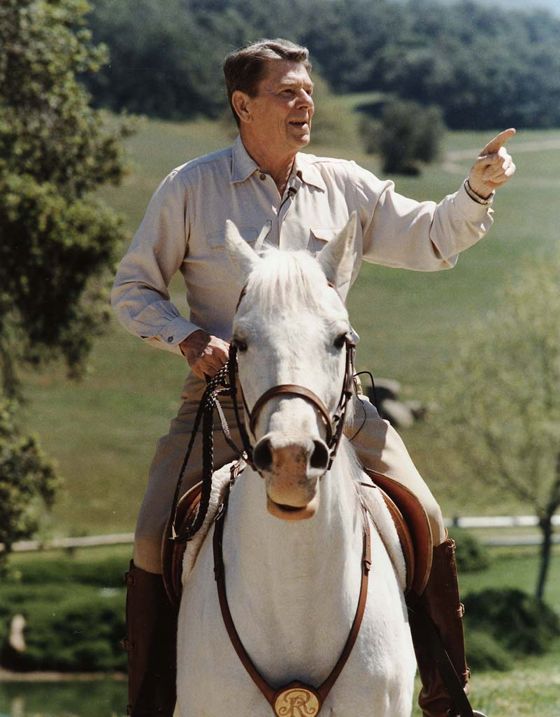

Both these figures were useful cultural icons, channels for feelings that needed an outlet, but they were mythological dead-ends. They didn't nourish the American spirit. When Ronald Reagan rode a horse back into the center of the American dream, even people who didn't care much for his policies succumbed to his imagery. They were just glad to see somebody, anybody, back in the saddle again.

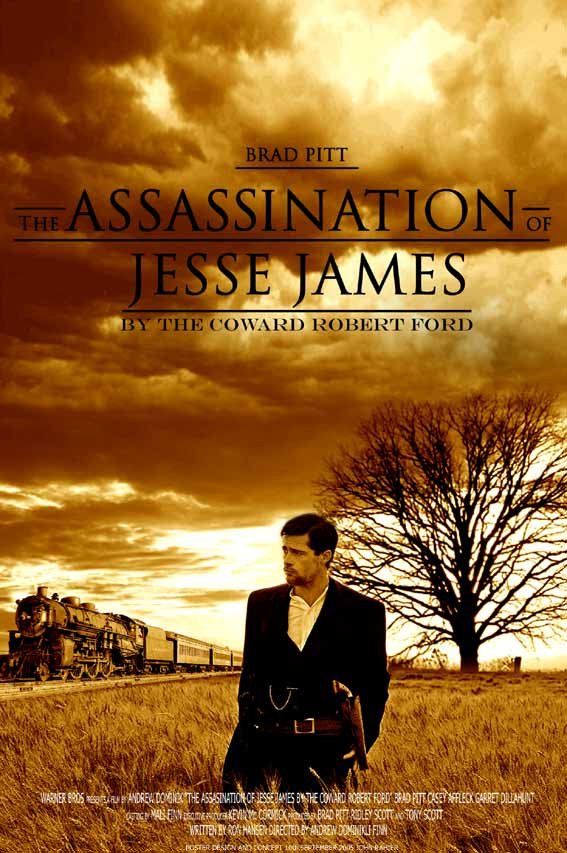

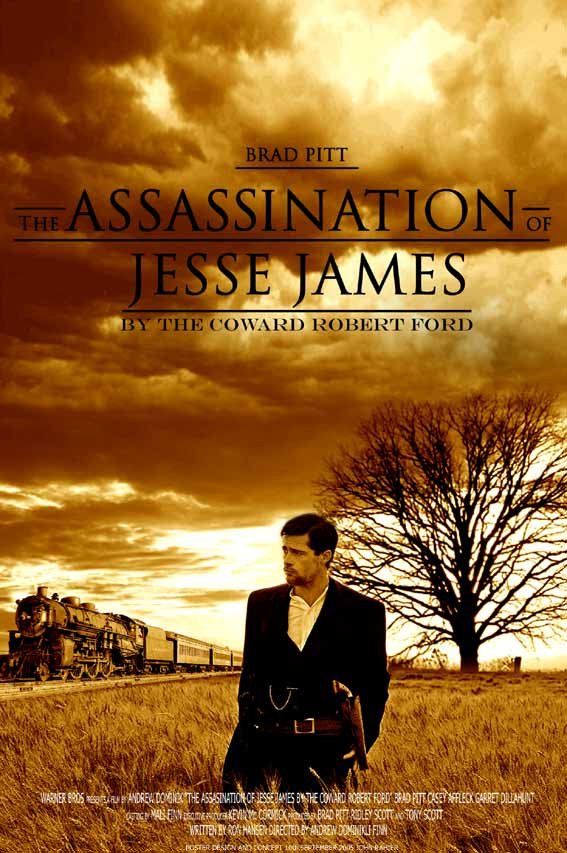

The cowboy hero, however, did not return to the movie screens of America, at least not as a regular player. In Hollywood, the cynical, revisionist or tongue-in-cheek Western was too firmly established as a mark of modernity. When the genuinely heroic cowboy hero did on rare occasions appear, he was greeted warmly. Films like Dances With Wolves, Unforgiven and Tombstone, and the TV mini-series Lonesome Dove, which paid due homage to the traditional Western values, were commercially successful. Dark or satirical or cynical Westerns, like Silverado and Wyatt Earp and the recent The Assassination Of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford, were not.

Hollywood drew the erroneous conclusion that people weren't really interested in Westerns anymore — whereas the truth was that they were no longer interested, indeed had never been interested, in dark, satirical, cynical Westerns . . . Westerns which projected modern despair and anxieties back into the American past. Americans have always looked to Westerns for images of redemption.

The Assassination Of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford offers at its center a brilliant study of collapsed, insecure manhood. It's a timely subject but the one subject a Western cannot embrace. We still look as we have always looked to Westerns for images of an authentic, non-neurotic manhood. A genuine cowboy hero can start out insecure about his manhood, or neurotic about it — like Ethan Edwards in The Searchers — but if he doesn't find redemption, of one sort or another, by the closing credits, we feel cheated, just as we'd feel cheated by a mystery thriller in which the mystery is never solved.

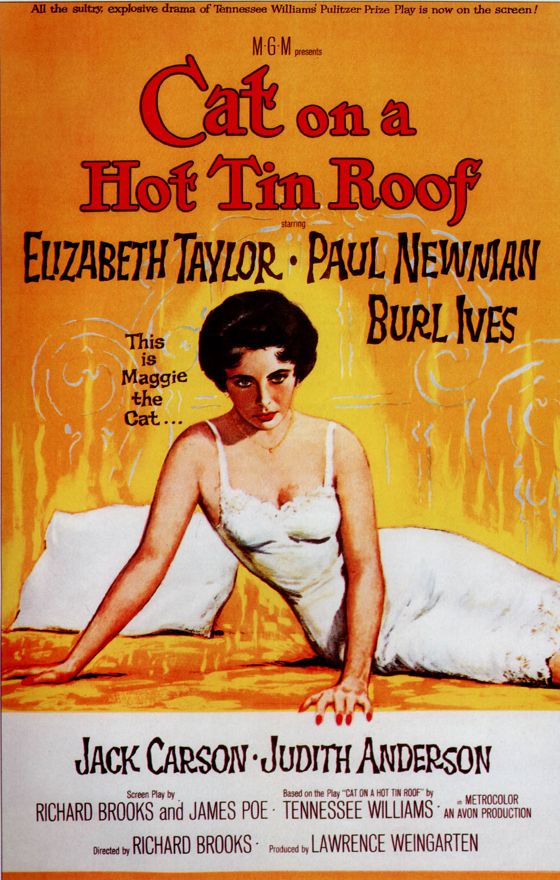

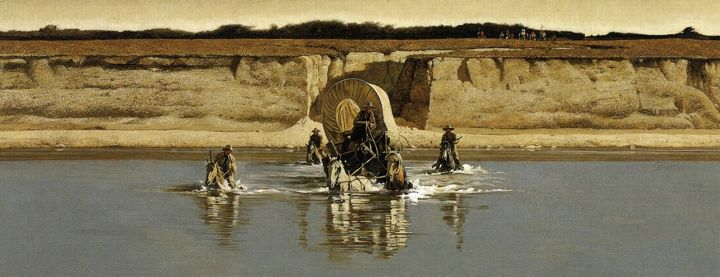

The Western genre was far from exhausted when the cynicism of the 60s shot it in the back. Women, for example, had never been fully integrated into the form, incorporated into the myth. They served as occasions for men to demonstrate virility or gallantry — which are fine things as far as they go — but Westerns rarely showed us the frontier from a woman's point of view, at least not with any consistency.

I would suggest that the role of the Western in the myth of America is hardly played out — it's just been ambushed on the trail. And like any cowboy hero worth his salt, it will get back up on its feet eventually and do what needs to be done.