Rio Grande, from 1950, the last film in John Ford’s cavalry trilogy, isn’t really about the cavalry, it’s about marriage, and like any serious work about marriage it deals with the subject of boundaries — boundaries respected, boundaries transgressed and boundaries transcended.

“Love is the mutual respect of two solitudes,” says Rilke, but in a marriage those two solitudes interpenetrate, in the partnership of daily living, in sexual intercourse and in the not unrelated phenomenon of bringing children into the world. To say that it gets complicated is to put it very mildly indeed.

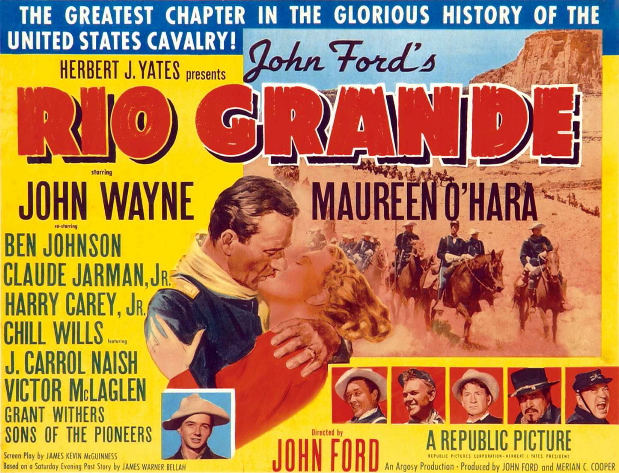

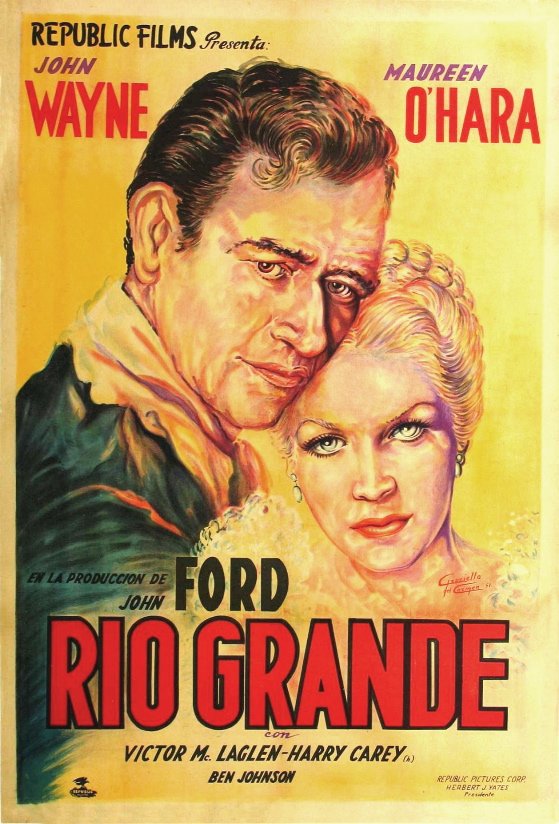

The river that gives this film its title is itself a boundary, of course, between two countries. Its very name embodies its divisive nature — on the Mexican side, the river is called the Rio Bravo, reminding us that people don’t always have the same names for the things that separate them, complicating communication considerably. The river is problematic for the film’s protagonist, Colonel Kirby Yorke, played by John Wayne, because Apaches living on the Mexican side are raiding into U. S. territory and he can’t follow them back to their refuge below the border.

He is compelled to respect the boundary and also to find a way out of the dilemma this places him in. He offers to put his command under the authority of the Mexican army for the purposes of a punitive expedition against the Apaches, who are bedeviling Mexicans as well, but national pride prevents the Mexican army from accepting help.

This is a fine set-up for a Western adventure film, but it’s only a metaphor for the film’s real drama, which concerns Colonel Yorke’s marriage.

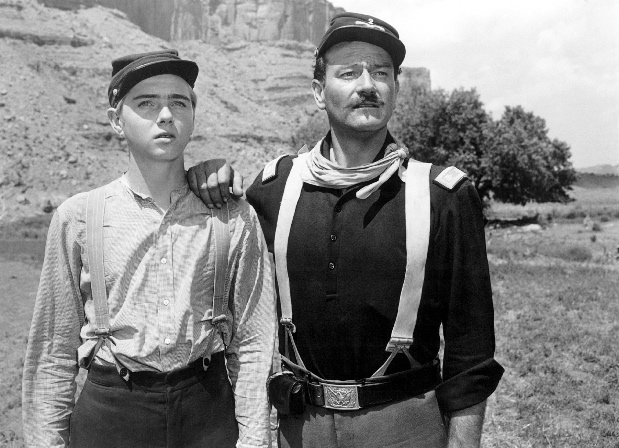

Yorke has been estranged from his wife for seventeen years, ever since, under orders, he burned down her family’s Virginia plantation during the Civil War, after which she came to hate soldiers, the profession of soldiering, and him. She took their infant son with her when she left him, but the son has become a soldier himself now, seventeen years later, against her will, and has been assigned to serve under his father at the remote fort near the Rio Grande.

Kathleen Yorke, played by Maureen O’Hara, shows up at the fort to purchase her son’s release from the army — but neither the son nor the father is prepared to sign the necessary papers, as they stare each other down across another kind of chasm, the awful chasm that exists between a father and son who don’t know each other.

Here, then, is one spectacularly dysfunctional family. Proximity saves them — proximity and the ritual etiquette of military life, of gallantry between the sexes. With personal passions roiling beneath the surface, they treat each other with respect, obeying the outward forms of civility, long enough to get to the bottom of things, to transcend their personal passions — bitterness, suspicion, resentment, shame, wounded pride.

The outward forms of civility, military and courtly, are all about respecting boundaries — establishing a border between people across which they have a chance of seeing each other as individuals.

But these borders exist to be crossed — and this is the ultimate profound and paradoxical message of Ford’s film. Yorke’s commanding general finally orders him to cross the Rio Grande in pursuit of the Apaches, in violation of international law. Yorke finally hauls off and kisses his wife, transgressing the line she has drawn between them. His wife offers to clean and repair his uniform — his soldier’s uniform, the symbol of everything she despises about him. The son crosses his own boundary into self-sufficient manhood, and the parents allow him to do it — and their re-established love for each other gives them the courage to do it.

People who see this film as simplistic, as an old-fashioned celebration of gallantry towards women, of military life, completely miss the point. The darkness in Yorke’s soul, the existential loneliness of his wife and son, are as devastating as any portraits of despair in a film noir. The rituals that save them are also the rituals that imprison them. There is no simple way to cross the Rio Grande — the cost of the crossing is enormous, almost more than the characters can bear. But the only salvation lies on the other side of the river.

Rio Grande is a film often damned with faint praise, but it’s one of the greatest of all American films, and in its deceptively simple, elegiac way, one of the deepest and wisest films ever made about marriage.

It’s a film whose sublime artistry is disguised by hiding in plain sight. Take for example the remarkable sequence in which Ben Johnson and Harry Carey, Jr. put on a display of Roman riding — galloping around a ring and taking a jump while standing on the backs of two horses running together. It’s a display enacted mostly for the Yorkes’ son Jeff, who must then try it himself, with mixed results.

Jeff has to learn a similar skill in life — finding a footing in the world of his mother and the world of his father, before he can come into his own as a man. And they must relearn how to work as a team in order to give him a chance to find that footing. The whole interior psychology of the film is thus summed up in a series of stunning visual images that on the surface read as a throwaway action interlude.

Cinema just doesn’t get any better or more eloquent than this.

[With special thanks to Dr. Macro’s High Quality Movie Scans for the illustrations.]