Paul Zahl (of The Zahl File) offers another meditation on an extraordinary bit of American culture from days gone by, the T. V. series One Step Beyond. If you don't remember it, or never saw it, Paul suggests that you might do well to keep it that way, just for your own peace of mind:

EXCRUCIATING — BUT WAIT, THERE'S MORE . . .

by Paul F. M. Zahl

Way Out, Roald Dahl's television show, was the ugly one, the ghoulish

one, the cruel one.

Twilight Zone was the high end of these early television gems of the fantastic — moralistic and righteous, at times redemptive and even hopeful.

Christ got at least two positive mentions in the Rod Serling scripts,

and the team effort showed in the artful results.

But in between, in between the cruelty of Roald Dahl and the justice of

Rod Serling, came the observing eye of . . . John Newland.

Newland is barely remembered today, but in the late 1950s and early

1960s (and even into the 1970s) he produced, directed, and acted in

scores and scores of television shows, mostly in the supernatural or

thriller line. Speaking of Thriller, Newland directed “Pigeons from

Hell” for that great series, scaring us all where it counts — early

childhood — and leaving us with that tender scar forever.

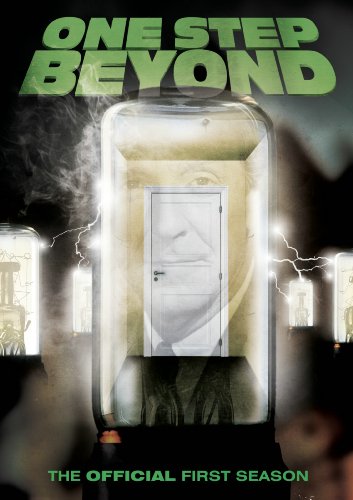

Newland's big achievement was hosting three seasons of a series concerning the

paranormal. The series was entitled One Step Beyond. It was created by Merwin Gerard and consisted of

thirty-minute 'docu-dramas' of supposed instances of possession,

ghostly presence, telepathy, and predictions of dreadful futures.

I have been watching One Step Beyond since the day it was birthed, in

1959. Almost all of the shows have been on video since the beginning,

as they were somehow in the public domain. And now — there is a God

— Paramount has released the first season of One Step Beyond in

splendid condition. Oh, and the music, especially the theme called

“Fear”, written by Harry Lubin, is the ultimate science-fiction/horror

theme. Anyone who is reading this would recognize it instantly. (I

listen to it right before bedtime every night. Mary loves it, too.)

But what has come to me in recent viewings, with an almost stunning

power, is a sort of personal truth about the inner spring of these

tight dramas. It is a truth about the supernatural in general, and it

springs from its source. These stories, with few exceptions that I can

see, are about love lost or love gone wrong. Someone has lost someone,

and is desperate with grief. He or she is completely naked to the

possibility of contact. Or someone has done somebody wrong, and the

guilt is killing them. Or, even, somebody hates somebody else, and the

hate gets objectified, in some kind of paranormal occurrence.

Below are some examples of what I am talking about. (“The Dead Part Of

the House” is available on the official Paramount DVD release (above), the

rest are available for download or viewing through YouTube or related

sites.)

Season One, Episode Nine: “The Dead Part of the House”

A widower hates his nine-year-old daughter because she survived an

accident that killed her mother.

He resents his little girl. And she knows it, and the child is

perishing for love, in front of his eyes.

She develops three ghostly friends, and in a benign move, these

supernatural friends are able to bring her father to his senses.

Phillip Abbott plays the father and conveys an irrational paternal

hatred, based on a love for his wife gone awry, that is painful to

watch, in the extreme. The little girl is entirely sympathetic, and so

completely shaken. Moreover, the child's kind aunt is powerless over

her brother.

It is Tennessee Williams, as far as I am concerned, on a claustrophobic

'50s television set, yet completely unself-conscious.

Season Two, Episode Seven: “The Open Window”

A painter of fashion models — his current model is played by Louise Fletcher —

observes a woman in an apartment across the way preparing to commit

suicide. She has been rejected romantically and her little

black-and-white four-walled world is killing her. Her disconcerting

monologue and preparations, overheard and observed, have several

antecedents in theater and movies. But the television camera closes in

on her, with dissection. It is impossible to watch. And it's only

1960!

As for the denouement, you'll have to see it yourself. But it's not

really about the genre, it's about human attachment severed and love

torn to shreds. How did Newland, who produced and directed, get this

out at an early hour Friday night? I don't think anybody at the

network or the sponsor must have seen it as serious, because it was

about, uh, ESP. But it was very serious.

Season Two, Episode 20: “Who Are You?”

A little girl wakes up in her bed and doesn't recognize her parents.

Her parents are loving, devoted, and dear. She runs away and finds the people she believes to be her parents. They, for their part, are living in a total darkness of grief, having

lost their own little girl recently.

The little girl we are watching is possessed of the spirit of the

other, dead little girl. And she is horrified by the attentions of her natural parents. And her grief-stricken 'real' parents are horrified by her.

This child is totally lost, but alive and real, a whole self of

yearning.

When “Who Are You?” is over and the implications of the first 20

minutes — these shows are all 29 minutes long — begin to sink in, the

situation becomes excruciating.

In short, don't watch this.

Just two more examples, but they can be multiplied by a score of others:

Season Two, Episode 32: “Delia”

Here is a humdinger, which begins so quietly and prosaically that the

middle section takes you completely by surprise.

A vacationing American man is trying to recover from a second lousy

marriage, and is drinking in a bar on a quiet island off Mexico. Another American, a sexy divorcée, at a table nearby, invites him

over. She is beautiful and the kind of woman most men would love to

meet under such circumstances. But he turns her down. He is

impossible.

He takes a self-pitying walk down to the beach, and half way down,

meets an extremely beautiful, refined, and quite un-sexy woman sitting

alone by a tree. She knows all about him, connects with him instantly

— as he with her — and they are completely and in a single minute one

in love forever. She is the lost and final love eternal, with eternal

eyes and never-ending smile.

He exits for a moment, comes back — and she is gone.

He spends the rest of his life searching for her, and ends up back on

the island, where he awaits her return, and drinks himself to death.

I won't give away the ending.

This little parable is the ultimate dream of romance between a man and

a woman. Drink to me only with thine eyes. I will spend my life

awaiting your return. And die in the process.

After you see “Delia” once, it becomes impossible to watch it again.

Get thee behind me. (Get thee to a nunnery)

He should have stayed with the giving brunette. Hélas, he didn't.

Season Two, Episode 33: “The Visitor”

This one is a celebrated episode. It starred Joan Fontaine, with Warren

Beatty, in either his first or second appearance ever.

It concerns a woman in older middle-age who has left her husband,

against his will, for the bottle; and has pulled herself completely

within herself at their cozy mountain get-away. A nice fire is burning

on a snowy night, there's plenty of money, and there's a bar full of

whisky. But a young man knocks at the door, his car having broken down

in the snow, and he is trying to get to the hospital where his young

wife is having a baby. He cannot get there.

Who he is and why he is there and what he has come to do? All is

revealed, neatly and affectingly.

Again, this is about love gone wrong, about malice as the consequence of hurt,

about grief causing people to go mad — and all on a minuscule set, with one

camera, two actors, and dread, with heart.

Don't see this one either.

I watch these episodes of One Step Beyond and have to tell myself not

to watch any more. They are saturated with grief. They are fistfuls of loss and love that

is separated, by the curtain of death, from fulfillment, even promise.

Yes, there is compassion — and none whatever of the ghoulish joy in

karma that Way Out featured every time. I would call these instances

of Baby-Boomer television masterpieces of wrecked emotion, and love's

attachment snapped forever.

How come these are so powerful — if “excruciating” means powerful? I would like to finish this article by trying to say why.

In the first place these are completely uncompromised one-act plays.

The camera prowls around — I honestly think of Rossellini and the

inquiring camera, maybe even the camera as protagonist, though I fear

that sounds pretentious. (I invoked Tolstoy once in a conversation

with Joe Dante, and he suddenly started to look at me coolly. I sure

wanted to withdraw that particular comment.) Yet it is true that John

Newland's camera moves around a lot, in interior spaces about the size

of a closet most of the time. In addition, his close-ups, which are

numerous, completely fill the screen. These are intimate dramas —

they are about one or two, or at the most three, characters. The

people's faces are tortured. They are anguished. The unflinching

close-ups mostly record grief and separation. What are ghosts

in these stories other than objectified presences of love become

unattainable? Thus the excruciating atmosphere of One Step Beyond.

There is one other thing:

When I was eight and nine years old and saw shows like this, I

definitely connected with the fear and dread. But

I didn't really get the truth. The psychology was completely at the

edges, or rather, out of the question.

I just knew, to my bones and my nerve ends, that something serious was

going on.

Too serious.

Twilight Zone, which saved the day, was more distanced somehow. It

didn't raise the resistance that was raised by One Step Beyond.

Neither could I have appreciated The Glass Menagerie. (Still can't

watch the last act.)

My advice to you, dear reader, is Skip This One. Sit It Out.

It's too close to home. Take away the supernatural part of it, and

there is only human loss.

Oder — and I truly wish I had done this when I was president of a

theological seminary — show “Delia'”and “The Dead Part of the House”

to a class for future ministers on . . . pastoral care. In the church,

and in the frayed and hungry world around us, you're going to encounter

quite a few Delias and a whole directory full of The Dead Parts of

Houses.