This September saw two important events in the life of our culture. One of them got a lot of attention, the other didn't. The attention went to the CD release of the remastered Beatles catalogue — an event that was important but in great measure symbolic. It was wonderful to have all those albums sounding so good — as good as CDs probably can sound — but it's not like the music had been unavailable before the remasters. The remasters were primarily an excuse to listen to it all again and begin thinking about The Beatles' place in history.

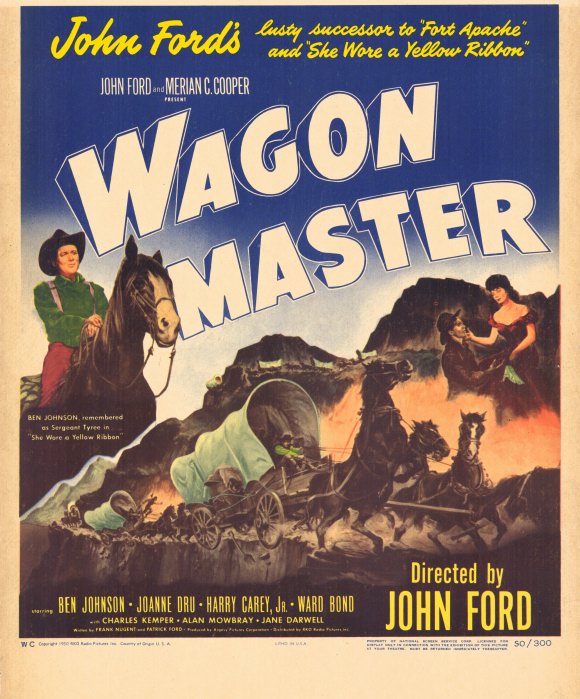

A week after the remastered Beatles catalogue was released, John Ford's Wagon Master appeared for the first time on DVD in the U. S. Its arrival didn't cause much of a stir. Wagon Master was a film that had been very hard to see, and for that reason lingered at edge of Ford's body of work, greatly admired by some but generally considered a second-rank effort in the Ford canon. The reviews of the DVD I've run across online, very respectful for the most part, have confirmed this status — the consensus seems to be that it's good to have the movie on DVD at last, even though its appearance is not likely to spark a major critical reevaluation, placing it in the same league as The Searchers, for example.

However, that's just where it belongs. Wagon Master may well be Ford's greatest film, his most perfectly realized film and, in some ways, his most radical film.

It is certainly one of his most personal films and he himself often cited it, sometimes in company with The Sun Shines Bright, as his favorite film. Harry Carey, Jr., who starred in the film with Ben Johnson, Ward Bond and Joanne Dru, said that Ford was in a good mood the whole time he was making it. This was not usual for Ford, to put it mildly — he had a vicious streak that almost always found its way onto the sets of his movies. It was nowhere in evidence on the set of Wagon Master, which Ford banged out in 30 days in something resembling a state of bliss.

One can imagine a few personal reasons for this. It was a low-budget film, made by his own independent production company, and it had no name stars in it. Ford had no executives on his back up there in Moab, Utah, where he shot most of it, and no star egos to keep in check. He made this film with almost complete freedom from studio interference.

Ford said that he fought a thousand battles with the studios in his career and lost all of them. Occasionally, with a studio head like Daryl Zanuck, he was fighting with someone he admired, grudgingly. But look at the changes Zanuck made to My Darling Clementine between the surviving preview version and the release version. They all coarsen the film, diminish its poetry and its subtlety. They may or may not have been wise changes from a commercial standpoint — we will never know — but the film would have been a greater work of art if Zanuck had kept his hands off of it.

Wagon Master is one of the only Hollywood films I can think of which does not open with a corporate logo. It's not marked up front with the brand of the nasty little men who controlled Hollywood by the simple expedient of exercising a virtual monopoly over film distribution in America. (If you think any of those guys would have survived six months in a free market for movies, you just haven't looked past the glamor of their artificially-created power.)

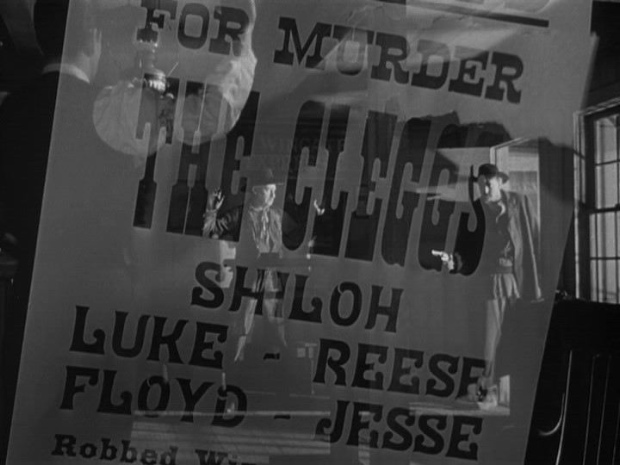

Instead of a corporate logo, Wagon Master opens with a dark image of a robbery in a small office, superimposed over a wanted poster of the robbers (above) — the Cleggs, a family of outlaws who will figure importantly in the story we're about to see. There's probably an ironic joke in this. When Ford tried to create his independent production company, he was robbed blind by the studios he still depended on for distribution — and there was nothing he could do about it. Working on a small profit margin, Ford's company eventually failed because the financial edge it needed was stolen from him by the studios he was trying to break free from.

So Wagon Master is brought to you by the Cleggs — like every other Hollywood movie from the era. Dumb, brutal thugs, the Cleggs will come a beggin' to the good folks of the film's wagon train, sponging off them, feigning gratitude, just waiting for the moment when they can exercise their ugly form of control. You can see the good folks of the wagon train as the people in Hollywood who actually did the work there, who actually made the films there, for the benefit of the dimwits with the guns. How delightful it must have been for Ford to set the dimwits up in this way, all the while knowing that in the story of this film, at least, they would get their comeuppance, and then some. No wonder he was in a good mood out there on the frontier, telling this tale.

But even if this joke is embedded in Wagon Master it's not finally what the film is about. It's a lot deeper than that, a lot more complex. On one level it's about the way men and horses move through landscapes — about the way horses behave when they're pulling wagons through rivers, about the way Ben Johnson sits a horse. The way Ben Johnson sits a horse is at the very heart of the film.

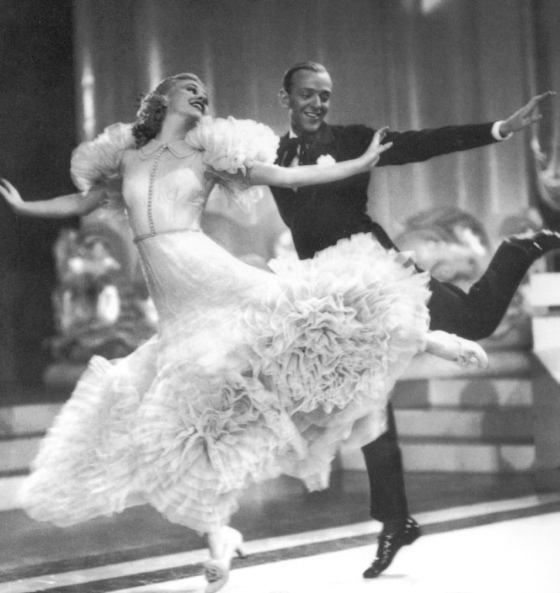

Johnson's grace in the saddle is every bit as magical as Fred Astaire's casual defiance of gravity in his dances, and every bit as cinematic. It helps to have some familiarity with riding to appreciate it. On the commentary for the new DVD, Harry Carey, Jr., himself a fine horseman, keeps crying out with pleasure at Johnson's way with a horse. (“That's how you get on a horse!” Carey will shout occasionally. “That's how you get on a horse!”) But even if you've never been close enough to a horse to smell it, you can feel the magic of what Johnson is doing — just as you can feel the magic of Astaire even if you've got two left feet.

As with dance, horsemanship suggests moral values. Treating a horse in a kindly, respectful way parallels the courtly partnership of a great pas de deux. Skill and ease on a horse, the physical virtuosity of it, evoke character, testify to history. Johnson, like Astaire, had the sort of virtuosity which can only be achieved through a lifetime of discipline, a lifetime spent in the saddle or in the practice studio.

Here's something to look for in Wagon Master — a scene where Johnson does his most spectacular riding, fleeing from a band of mounted Navajos. He and his horse traverse rough ground like water flowing over a rocky stream bed. At one point Johnson loses his right rein at a full gallop downhill and leans down to retrieve it like a short-stop scooping up an easy grounder. Johnson once said of a spectacular ride in another Ford film, “I was just a passenger on that one.” This gets close to the mystery of riding — a great horsebacker is always a great passenger, in tune with his mount, with the ground they cover, in tune therefore with the earth but creating new possibilities of movement in space, like a dancer. It is a combination of mastery and surrender, of harmony and challenge, an image of human potential at its extreme limits.

When you see Astaire dance, you know he's going to get the girl in the end. When you see Johnson ride, you know he's going to save the dream of the Mormons migrating west.

You know he's going to get the girl, too. The “love story” between Johnson and Dru, playing a slightly worn showgirl, is one of the deepest in all of Ford's work, and one of the sexiest, though Ford doesn't even give them a fade-out kiss. It's all about the gracious courtship of a woman who has long ago given up dreams of gracious courtship. It's about her surprise at this, and mistrust of it, and final surrender.

It's a romance that plays out in physical terms, in the way he moves and the way she moves — a complicated sexual display in which every casual touch or glance is erotically charged. In the last two-shot of the couple, riding on the seat of a wagon, nothing has been spoken about what's ahead for them, but you can see it in their eyes. It's almost indecent, what you see in their eyes.

Wagon Master is a film made up of closely observed physical phenomena which Ford has somehow invested with moral and spiritual meaning. Good and evil don't need to be given symbolic markers — we see them at work without masks, without name-tags. In all of art, I think only Tolstoy, in War and Peace, got anywhere close to this effect.

In Wagon Master, Ford shot a thoroughly convincing documentary about the world of spirit . . . about spirit made flesh, literally. Other films have tried to do this, but Wagon Master makes even the best of them, like The Diary Of A Country Priest, look ham-handed by comparison.

The ending of Wagon Master is as odd and unconventional as its opening. Just as the settlers get within sight of their promised land the narrative deconstructs itself — we are presented with a montage of discontinuous shots. Some seem to show the characters riding on to a new life, others are shots from earlier in the film. Time dissolves, the wagon train moves on, in the mystical dimension the film has conjured from its meticulous rendering of actualités.

To put it very bluntly, as Ford might have, to get us off the scent of his piety and faith, Wagon Master is a God-damned miracle.