[These thoughts on Murnau's The Last Laugh contain plot spoilers — don't read them unless you've seen the film . . . instead, go see the film, one of the greatest ever made.]

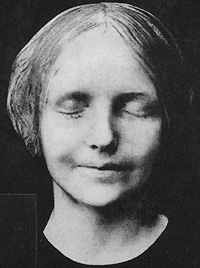

The original German title of Murnau's masterpiece The Last Laugh was Der Letzte Mann, “the last man”. In English this phrase can have a positive connotation, something like “the last real man”, or “the last man standing”, but in German it only connotes degree or place in a literal sense — something like “the lowest man”, “the least of men”, “the last man in the pecking order”.

In the film, the title is explicitly but somewhat ironically linked to the Biblical phrase “the last shall be first, and the first last“. This saying of Jesus appears four times in the New Testament but only in the Synoptic Gospels (i. e. not in John) and in a couple of different contexts. The phrase is often read as simply contrasting the rich and powerful with the poor and oppressed, who will somehow triumph in the fullness of God's justice, but this is a misinterpretation in at least two cases. In those passages, “the first” Jesus refers to are his own self-righteous followers who feel they have some special connection to him and to God because of an imagined advantage they possess — either from having “seen the light” before others, or having spent more “quality time” with him.

Jesus is making the point in those cases that status in some imaginary “Jesus club” has nothing to do with true righteousness, as judged by God. He is offering a rebuke not to those with power who oppress believers but to believers who lord it over their fellow believers. This is obviously not a congenial message to the organizers of religious institutions, for whom sanctioned membership in the official “Jesus club”, with attendant privileges, including eternal salvation unavailable to others, is a prime selling point and recruiting tool.

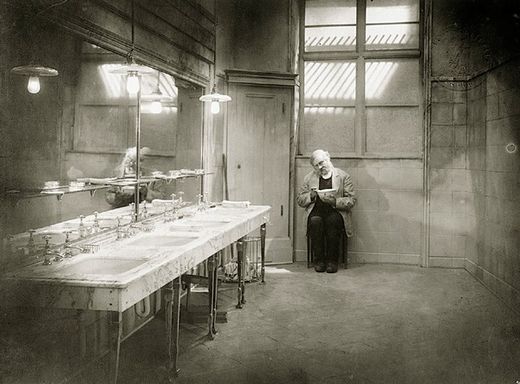

Jesus's phrase is obviously deeply ironic, and it is introduced ironically in Der Letzte Mann. It appears in the very odd epilogue to the film — the preposterous reversal of fortune in which the doorman demoted to restroom attendant receives an unexpected inheritance and suddenly becomes a man of wealth and privilege, elevated even above the position whose loss had crushed him earlier.

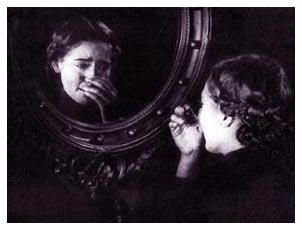

This epilogue follows the film's only intertitle, which is interjected after the washroom attendant has reached the depths of defeat and despair. The intertitle is unrelated to the narrative proper and represents the filmmaker addressing the audience directly and commenting on the narrative. He says that the defeat of the protagonist is how such stories end in real life but that he (the filmmaker) is not content to leave the matter there and will instead, out of love for the protagonist, supply his story with a happy ending.

This is, to put it mildly, disorienting. We're being told, in effect, that the happy ending we're about to see is a fraud, or a fantasy — and that's exactly how it plays. The new dream life of the protagonist is exaggerated and surreal, moving beyond the precincts of expressionism into the realm of the purely fantastic. The protagonist doesn't just enjoy a fancy meal, he stuffs himself from a dessert concoction the size of a small building. He doesn't just serve caviar to his best friend, he shovels gobs of it from a vast pot onto his friend's plate. The whole things seems to be an insolent challenge to the audience, asking, “Do you buy this?”, “Is this what you wanted to see?”

The first shot of the epilogue shows a group of silly-looking rich folk reading a newspaper account of the protagonist's reversal of fortune and laughing derisively — as though they know how ridiculous it is. It's hard not to see these people as Murnau's image of us, of the audience, cynically demanding happy endings for “the least of men” all the while knowing that happy endings are only for the privileged, for the self-styled “first” of men. Exceptions to this rule are the stuff of comedy, of satire or farce.

Murnau shows us the newspaper account the rich folks are laughing at, and it's this account, ironic and unserious, which quotes Jesus's saying, rather frivolously — “It looks as though the old Biblical saying is being fulfilled, that 'the last shall be first'”. Then we are shown the rich folks laughing even louder.

Murnau was apparently forced to add the happy ending to the film, but he subverts it mercilessly, suggesting that Jesus's observation about the first and last is just a joke to most people, something that only applies to the dreamworld of popular entertainment. It's hard to imagine Jesus disagreeing with him.

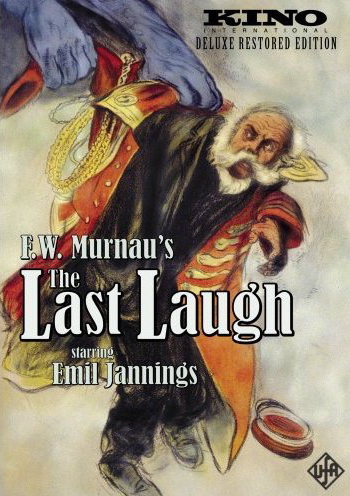

In a film about the making of Der Letzte Mann included on the new Kino DVD edition of the restored film, it is suggested that the story is an anti-militaristic fable — the doorman's obsession with his uniform as a status symbol being a metaphor for German society's obsession with military adventurism. This of course casts Murnau in the best possible light as a “good German” — going against the grain that led Germany to start the Second World War. Murnau and his screenwriter Carl Mayer may have had some such criticism of Germany in mind, but it's hardly the heart of the film — which I think is much closer to the Biblical text they reference in their story's title and in the newspaper article their rich folks find so hilarious.

This is not to say that Murnau and Mayer (a Jew) meant their film to be interpreted from a “Christian” perspective, but it seems inescapable to me that they were using a Christian image — die Letzten, as Luther translated the Greek of the New Testament, εσχατοι, “the last men” — to express their deep love of one beaten and defeated man, and their anguish over his oppression by a cynical and arrogant and hypocritical society, a “Christian” society.

Interestingly, and tragically, Carl Mayer died a “last man”. Like many Jews in the film industry he fled Nazi Germany and ended up in England, where he had trouble finding work. He developed cancer, which was apparently poorly treated, due to to wartime strains on medical facilities, and died with 23 pounds and two books to his name. I'd love to know what those two books were.

I must add that the recent restoration on the Kino DVD is miraculous. The film was shot to produce three negatives, one for German release, one for American release and one for general international release elsewhere. The footage for the German release is far superior in terms of framing and action and has been reconstructed from a variety of sources for the version found on the new Kino edition. The quality and beauty of it are really breathtaking. This is probably the best version of the film ever available to American viewers in any form.