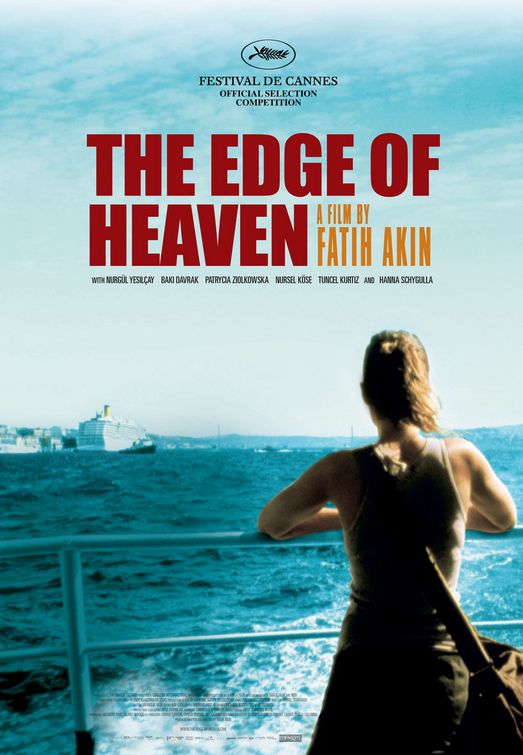

My friend Cotty writes to recommend the film The Edge Of Heaven and to record his disappointment at the small size of the audience he saw it with. He concludes:

Strange times in the movie business. Five independent distributors have disappeared or been absorbed or are under severe threat, all within the last sixty days. Warner Independent, Picturehouse, New Line, Vantage, and ThinkFilm all going or gone. Who will make and distribute movies that rely on audiences caring to leave the house just for the sake of the experience of the emotional connection that only movies can bring?

Despite complaints from disappointed or estranged film-makers, the fault, I think, lies not in our stars, or their managers or their studio enablers, but in ourselves. If we don't go, why should they build it?

Perhaps the Obama candidacy can revive a sense of connection, can remind us of a common experience of America's great strength in diversity, her powerful e pluribus unum past and the blunt necessity of shared response to global problems. But it will come too late to help Strand Releasing [distributor of The Edge Of Heaven] in its attempt to bring you a lovely and cinematic time in the darkened common room that is a movie theater.

Good thoughts for these bad movie times, but I'm inclined to play the Devil's advocate and argue that the public is never wrong — that if good people shun good films, then there's something wrong with the films, at least as works of popular art. Films can be good and still not be works of popular art, but why are there so few good popular films?

The example of Obama's candidacy does, I think, point to the answer. Four years ago the American public rejected, by a slim margin, John Kerry, who would (I think we can all now say in hindsight) have been a better President than George Bush . . . but he wasn't the sort of President most Americans wanted. His candidacy reeked of Democratic Party caution and calculation, his case to the public was cast in Senatorial, which is to say, conventional Washington, rhetoric. He was a new version of the same old thing, so why not stick with the familiar version of the same old thing already installed in the White House?

If John Kerry and George Bush really are the same old thing, fundamentally, why not choose the guy you'd rather have a beer with? If the latest art-house release and the latest action-hero extravaganza are just variations on outdated paradigms, why not go see the one with the loudest explosions, the one everybody at school is going to be talking about next week?

One can come up with rational arguments against these propositions — like the war in Iraq, for example, or the mind-numbing boredom of too much CGI — but culture, political and artistic, is not a purely rational thing. It's too easy to convince yourself that George Bush might have known what he was doing when he invaded Iraq, or that the next Spiderman film is going to kick ass.

When politics and/or popular art don't reach something higher in us than business as usual, than commodity merchandising, we tend to rebel and refuse to make sensible distinctions between good and bad products. We often act against our own best interests out of a kind of unconscious rage . . . because we don't want politics or popular art to be about “products” at all, or not only about products.

I think this explains why Republicans have been able to persuade lower-income Americans to vote Republican against their own economic interests by pushing “values” buttons — by suggesting that gay marriage, for example, is an assault on “the traditional family”. It's irrational, but to such Americans even an irrational vote in favor of “the traditional family” makes more sense than pretending that one corporate-sponsored political product is better than another.

On the left, the phenomenon would explain all the votes for Ralph Nader in 2000, which may well have cost Al Gore the Presidency. More importantly, it explains the millions in the last two elections who voted with their rear-ends by planting them firmly on their couches and staying away from the polls altogether. Again, it seems irrational, contrary to self-interest, but in fact reflects, at least on one level, a perfectly rational disgust with the whole system.

This year the Democratic Party machine, with its support for Hillary Clinton, tried to offer Americans an even newer version of the same old political product — a female political product! — and came very close to putting it over on us.

Obama beat her not because he had a more effective mask covering his political product-ness — a black political product! — but because his whole campaign, everything about him, felt genuinely different. He spoke in a new kind of language which we've hardly ever heard from Washington, he raised money from small-time donors which made him independent of the Democratic Party machine, he sent out an army of organizers who didn't look or act or talk like party hacks.

And yet . . . he spoke to old values, to popular concerns, to the shared e pluribus unum past Cotty mentions, one that is still with us, still capable of inspiring us.

The lesson in this for me, as it relates to movies, is that the mass of people don't really want anything that has the stink of current movie logic on it — neither wonderful little art-house movies nor committee-made would-be blockbusters. They'll settle for them, if they can't get anything better, but in smaller and smaller numbers and with less and less enthusiasm.

They want something that feels different on a molecular level, the way Obama's campaign feels different on a molecular level. They want a change, a fundamental change — even though that change, like Obama's rhetoric, may take us back to old, forgotten truths.

Movies, like Obama, don't have to choose between an isolated integrity and pandering to the tastes of the masses — they can choose another path . . . honoring the tastes of the masses, as Obama has honored the aspirations of a broad public. The key is believing that the aspirations of the broad public are worth honoring, and trusting the broad public to respond. It requires a leap of faith, a violation of all conventional wisdom, a wild kind of hope. It requires, in short, something as improbable as Barack Obama's candidacy.

So my question to filmmakers is, as one Obama bumper sticker puts it — Got hope?