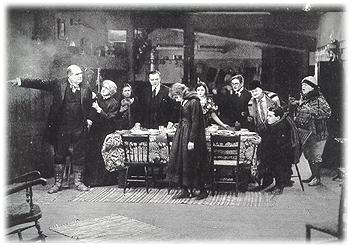

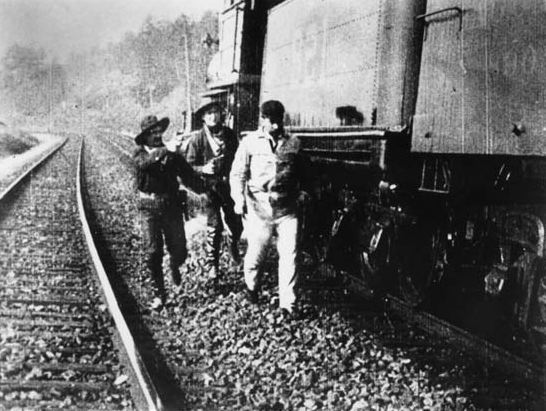

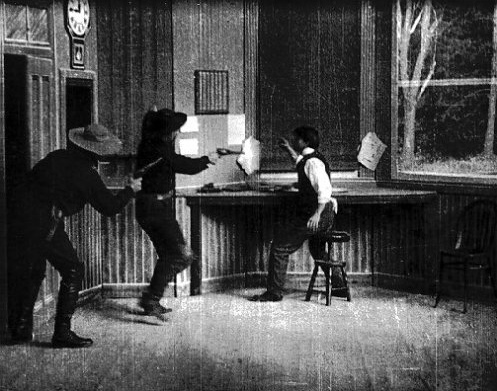

If you look at narrative films made in the first decade of the 20th

Century you'll be struck by a very odd aesthetic anomally. Scenes shot

out of doors will often be dynamically composed, emphasizing spatial

depth in the image — they look modern and can be extraordinarily

beautiful. Scenes shot on interior sets will, by contrast, be framed

head-on, creating the impression of a shallow space — this, combined

with the obviously painted sets, mostly using flats, looks decidedly

cheesy to modern eyes.

Why did audiences accept this violent contrast of cinematic practices

within the same film?

One reason, of course, is that the interior sets reminded audiences of

the stage, where painted sets and proscenium framing were familiar.

They could think of these scenes as filmed stage-plays, which is how

story-based movies were often defined and sold. The exterior scenes,

on the other hand, reminded viewers of pre-narrative cinema — the

“actualities”, short scenes of picturesque places and real events,

which were the primary content of movies presented as novelty

attractions.

These actualities tended to be agressively “cinematic”,

emphasizing the illusion of spatial depth to show off the magic of

movies — their ability to create the convincing illusion of a real

place on the other side of the screen.

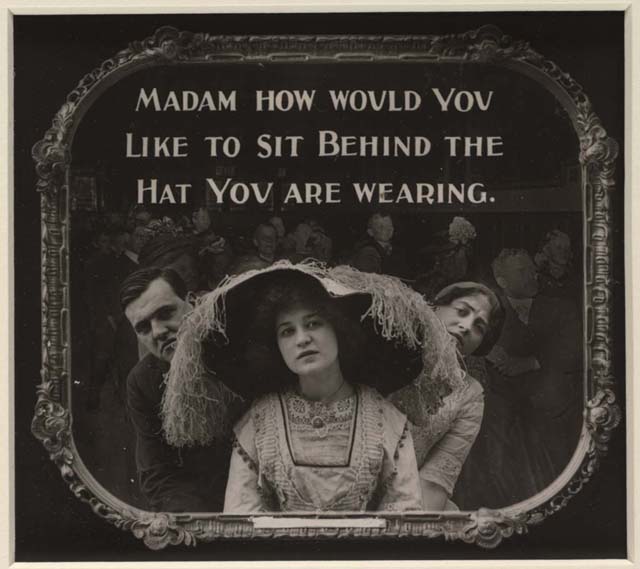

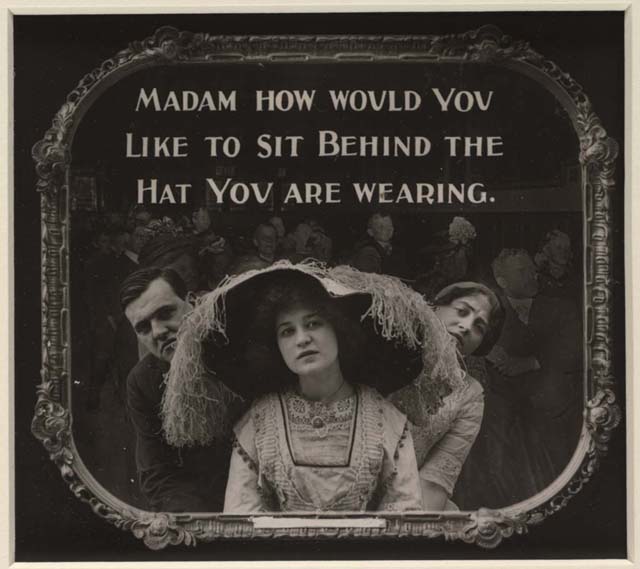

Novelty-attraction actualities were often part of a theatrical

presentation

which featured live performers as part of a variety bill — so viewers

were accustomed to an alternation of cinematic actualities with

theatrical stage-bound scenes.

The narrative structure of early story films was apparently enough to

knit the two types of cinematic practice into an aesthetic whole for

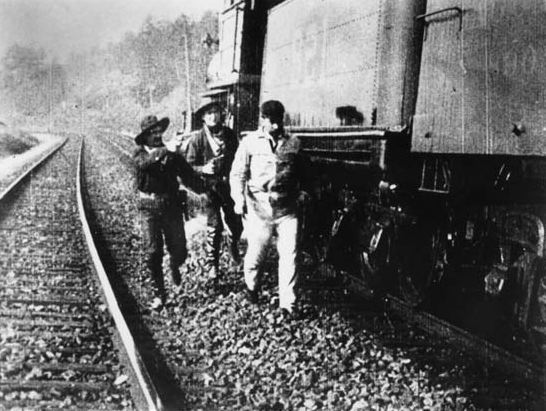

viewers of the time. Indeed there's a curious Edison film from

around 1904, not part of the regular Edison release schedule, which

shows a

group of people making its way by various means of transport from one

end of Manhattan Island to the other. There's no connecting narrative

— the shots just seem to be a series of “actualities” linked only by

the presence of the same characters in each sequence. It's been

suggested by film scholars that these sequences may have been shot as

“entr' acts” for a stage play, showing the play's characters moving

from location to location in the story — something to pass the time

and amuse an audience while the stagehands shifted sets behind the

projected images.

If in such a production you just replaced the scenes on the stage sets

with filmed interiors, shot head-on against painted theatrical

backdrops,

you'd have a pretty fair paradigm for an early narrative film.

Even imagining how such anomalous cinematic approaches could have been

reconciled for viewers within the same film, it's hard not to see the

results as crude. But such anomalous approaches have almost always

been a part of cinematic practice — and the momentum of narrative has

always been able to reconcile them.

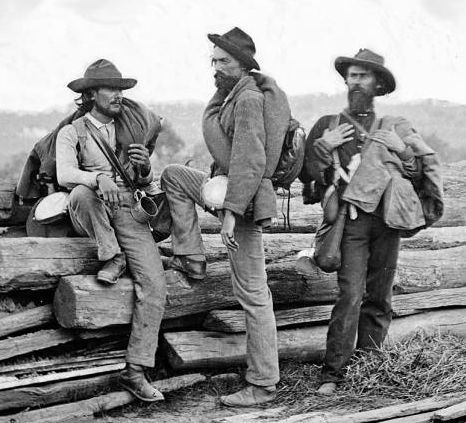

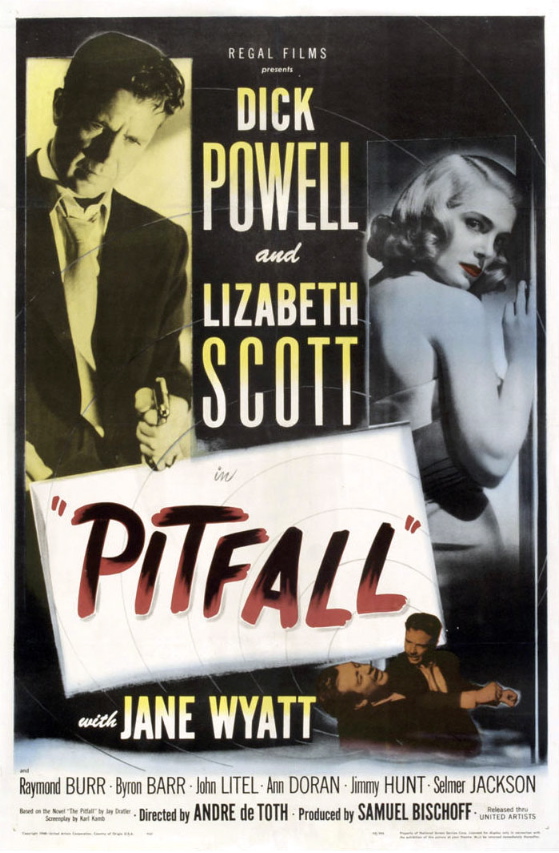

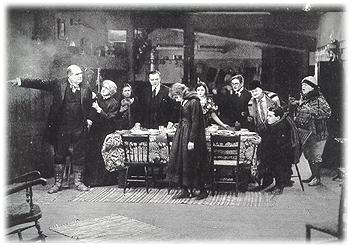

Look at John Ford's Stagecoach

again and see how stunningly photographed images of real locations

alternate with studio work (above) in which sets and back-projections stand in

for exterior locales. It's objectively weird, aesthetically

inconsistent, but our eyes, accustomed

to back-projections in films of this era, don't read it as such.

The conventions are always shifting, of course. The studio-built

interior sets of Stagecoach (above) are fully three-dimensional and

convincing as actual locations — a far cry from Edison's patently

two-dimensional interior sets painted on flats. But Ford's

back-projection exteriors are convincing only to the degree that we

choose to be

convinced by them, as Edison's audiences chose to be convinced by his

artificial interior sets.

The history of the shift from “theatrical” to fully dimensional interiors in movies would be fascinating to chart.

One of Griffith's main formal concerns in the Biograph years was

developing a way of staging and photographing interiors on sets in

spatially interesting ways, to create a stronger illusion of being in

real rooms — but he never totally abandoned proscenium framing.

Why?

I'm beginning to think that proscenium framing for interiors continued

to have a degree of glamor for filmmakers throughout the silent era, by

evoking the prestige of the stage.

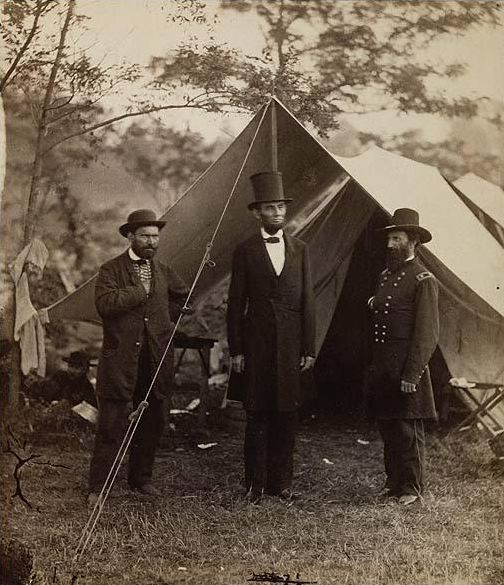

Twice in Erotikon, from

1920 (above), which has elaborately constructed and

convincing interior sets, such a set is introduced by a wide, head-on

proscenium type shot — before Stiller moves in and starts shooting the

room as though it were a practical location, sometimes even shooting in

mirrors that reflect the wall behind the camera, utterly abolishing the

theatrical mode by showing us the “fourth wall”.

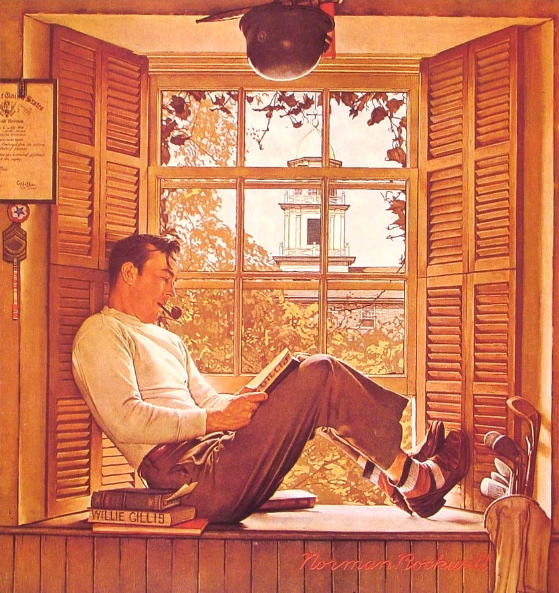

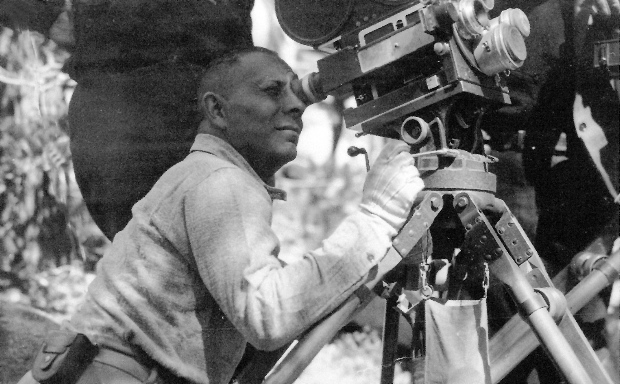

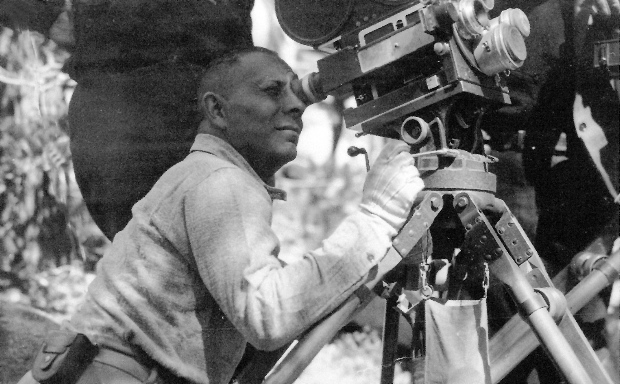

In Peter Pan, Herbert Brenon (above, with camerman James Wong Howe and Betty Bronson) does something similar with the opening sequence

in the nursery — which he starts out showing only from angles that

would have been available to members of an audience seated in front of

his set, but then proceeds to penetrate from angles only available to

performers inside the set.

Both Erotikon and Peter Pan were adaptations of popular stage

plays, and the filmmaker in each case may have wanted to remind viewers

of the film's prestigious theatrical provenance.

Von Stroheim seems to have been the first film artist to abolish the

theatrical mode for interiors as a matter of basic aesthetic principal,

and he was followed in this approach fairly consistently by Murnau as

well. From them derive the dynamic spatial interiors of Renoir

and Welles.

[With thanks to shahn of sixmatinis and the seventh art for a recent post which got me thinking about this subject again.]