American Gothic

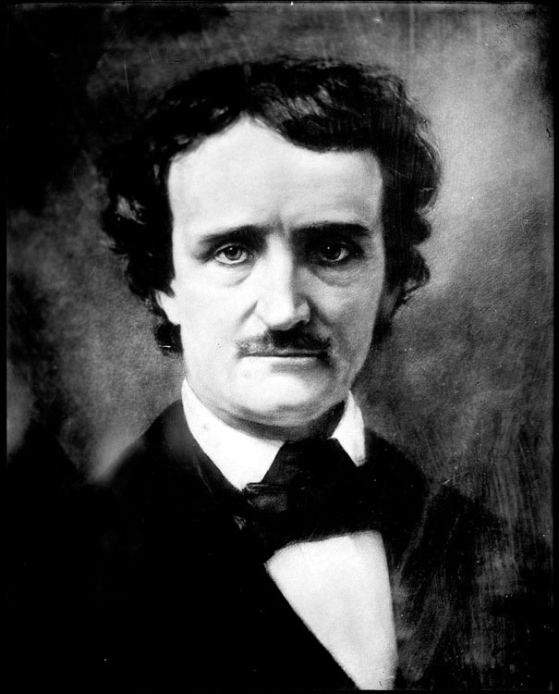

In the broadest perspective, film noir belongs in the long tradition of American Gothic fiction, that dark vision crystallized in the tales of Hawthorne and Poe. A kind of counterbalance or reaction to American optimism, this tradition can have an almost savage quality, as though the decision to explore the shadowy realms of the American psyche has led to a determination to follow that path to its uttermost end, to the absolute limits of nightmare.

D. H. Lawrence saw in this tradition a desire to ritually enact the decay of European culture as a kind of psychic prelude to the birth of a new culture. Leslie Fiedler saw the darkness at the center of so much American art as the product of a stunted manhood, which embraced despair and death because it could not find its way to maturity.

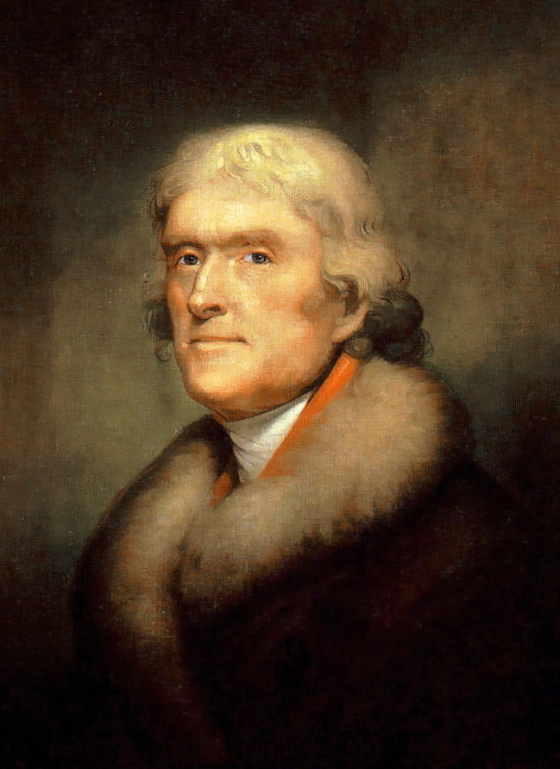

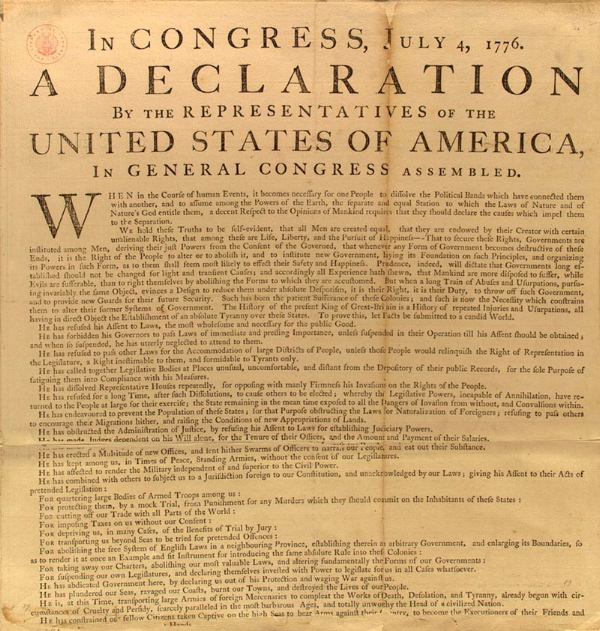

However the tradition is explained, it must on some level reflect the enduring contradiction between America’s ideals and its actions. The nation’s founding document, announcing that all men are created equal, was written by a man who owned slaves. In the gap between a radical, transformative announcement such as this and its author’s actual life, corrosive subconscious anxieties are bound to breed.

The Genre Of the Grotesque

Europe’s own literal effort at self-destruction in WWI, and the anxiety this produced in a nation that both rejected the old world and still looked to it for guidance, led to a curious new genre in American movies, reminiscent of Poe — the genre of the grotesque.

In this genre, grotesque figures, deformed or mutilated, enacted tragic scenarios of revenge against the “normal” world, in a vain attempt to assert a private nobility, a private honor. This genre made a star of Lon Chaney, who specialized in tragic grotesques, and is often read as a precursor to the horror film of the 30s, but it was really something else — a way of dealing with the images of death and disfigurement associated with the Great War, a way of expressing the fear that civilization had been deformed by the conflict. Audiences of the 20s could not help but have associated Chaney’s misshapen characters with the mutilated veterans of the battles in France.

This genre died out with the coming of sound, mutated into the campy Grand Guignol of the classic horror film, but it’s worth noting it here because it represents the same sort of coded response to WWI that the film noir represents to WWII — a way of nursing wounds that nominal “victory” had not healed.

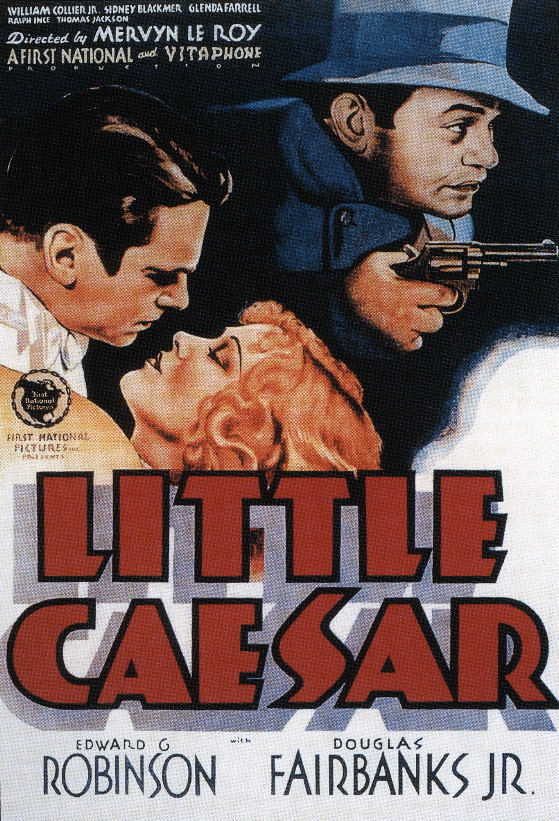

Crime Drama

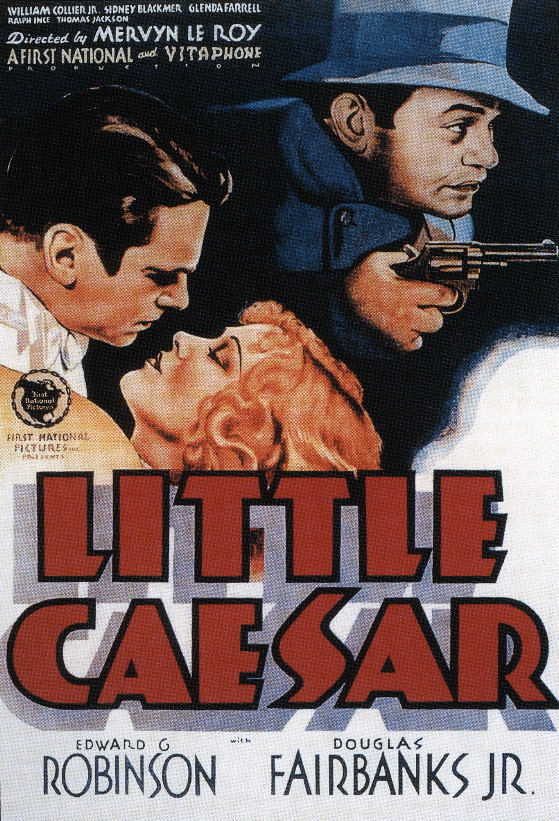

The underworld crime drama of the 30s was a response to the Depression and to all the social ills it spawned and exposed. It allowed us to enter the underworld of American society — to revel in the destructive rebellion of underworld thugs, expressing a rage against the system felt by many, while still containing them within a conscious code of values which demanded their death, which still posited forces of order and decency which would prevail in the end.

Hardboiled Detective Fiction

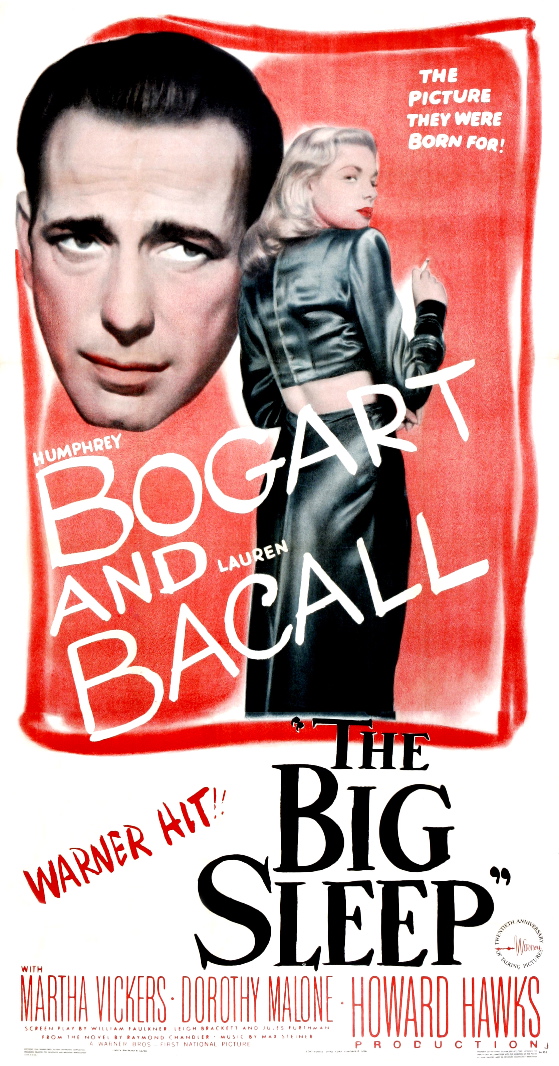

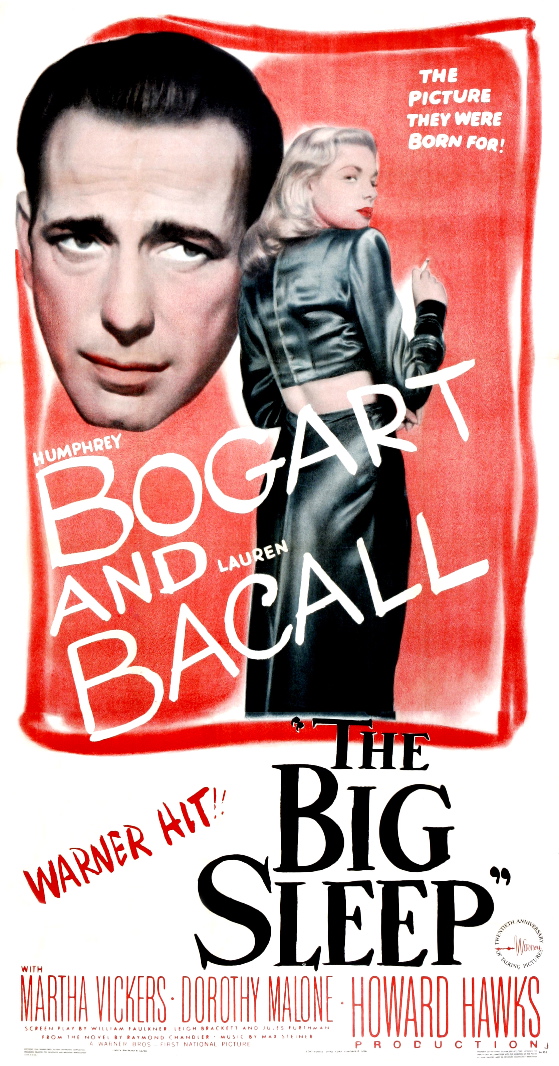

A variant on the crime drama was the pulp detective fiction of the 30s and 40s which sent a knight errant into the dark streets, the moral chaos of American life, in search of truth and rough justice. Such fiction most often involved a mystery to be solved, and its solution constituted a triumph over the moral chaos. Pulp detective fiction allowed us to take a brief vacation on the wild side in the company of a guide who was sure to get us home safe again.

Noir

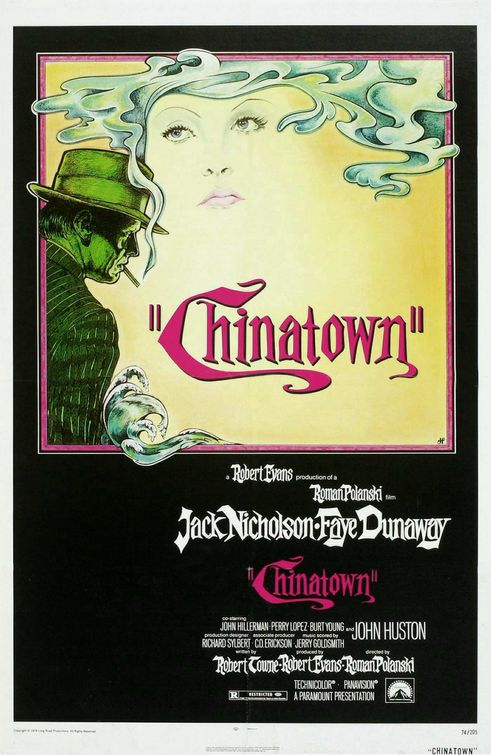

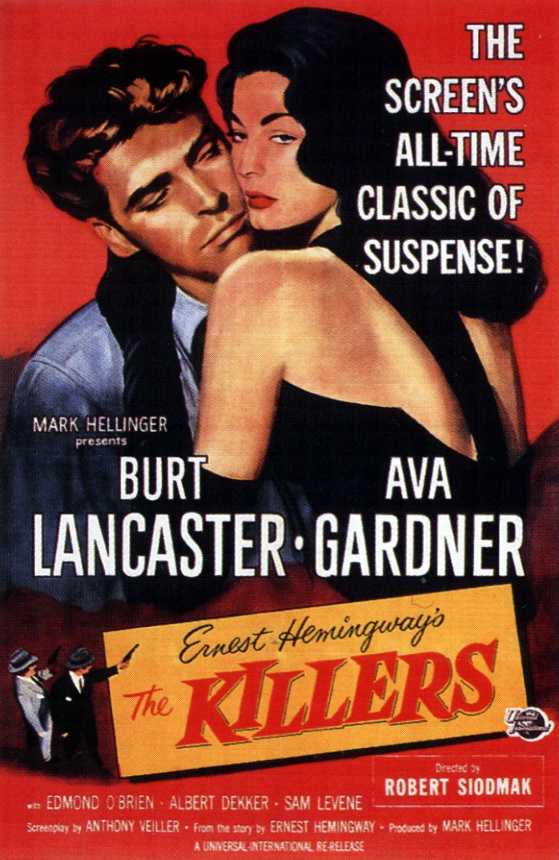

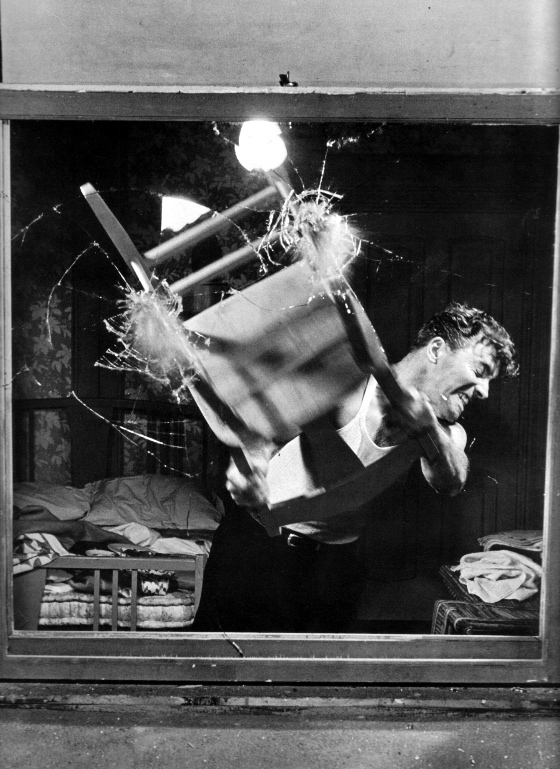

Film noir, as it evolved after 1945, in the wake of a war America participated in fully, sending millions of its young men and women into the fray, and in the wake of the sheer unimaginable fact of the atomic bomb, drew on the traditions of the crime drama and hardboiled detective fiction, but it became something different.

It lost its faith in the forces of order and decency, and in the reliability of its protagonist guides. It posited a moral maze which had no logical solution, no center and no exit points. It

offered the frisson of pure existential dread without an easy cure.

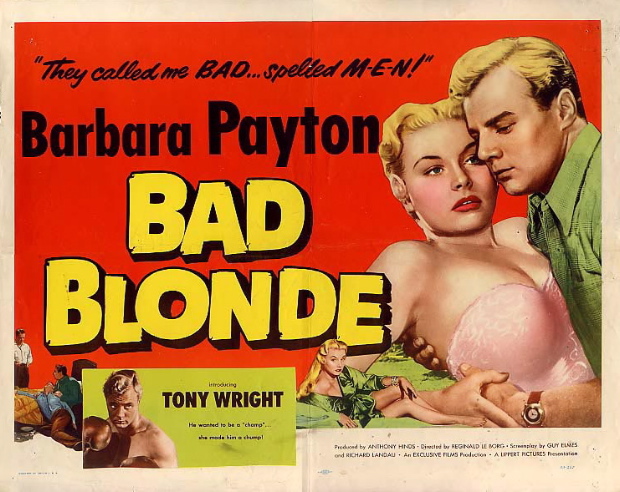

Fiedler’s spiritually stunted males became easy prey to strong women — femmes fatales who could destroy a man at will. (In film noir, a strong woman might just as easily save a collapsed male, but purely as an act of generosity — not because the male deserved saving.)

A protagonist in a true film noir might find himself fated for destruction by a corrupt justice system, by an innocent mistake, by a malevolent coincidence or by some dark inner compulsion which he can’t

control. In all cases, he finds himself in a labyrinth with a compass that has lost its pointer, a thread that runs out short of escape.

Near Noir

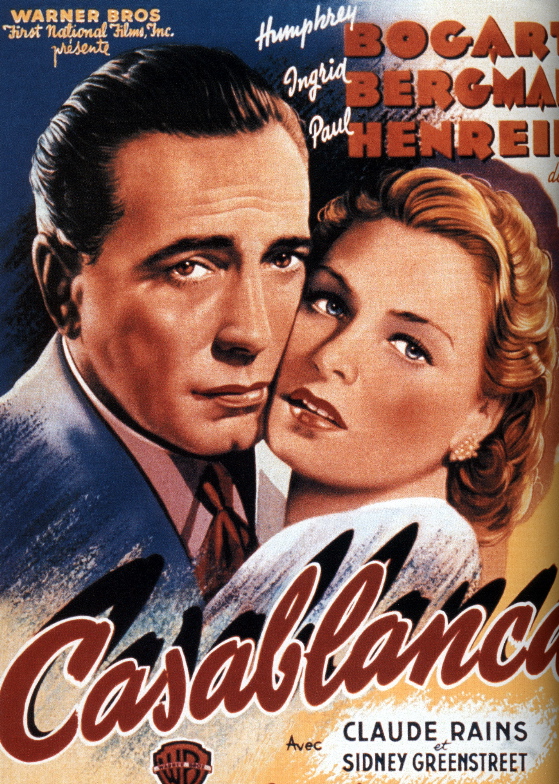

There are many films called noir today which don’t really fit the definition offered above. They are variants of the 30s crime drama, docu-noirs like The House On 92nd Street, for example, which may borrow the expressionistic visual style of the true noir but ultimately validate the agents of the state who will set things right in the end. There are also a number of noir-inflected detective mysteries, like Laura, for example, which give us a reliable guide through the moral maze and bring us safely out of it at the end.

This is true even of John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, the most noir of the classic detective thrillers. Sam Spade does the right thing in the end, rejects the femme fatale

and remains true to his essentially decent code. But he’s more neurotically conflicted about this code than the average hardboiled detective — you get a sense that he’s beginning to suspect it’s all pretty meaningless. In that existential anxiety we see the roots of the true film noir.

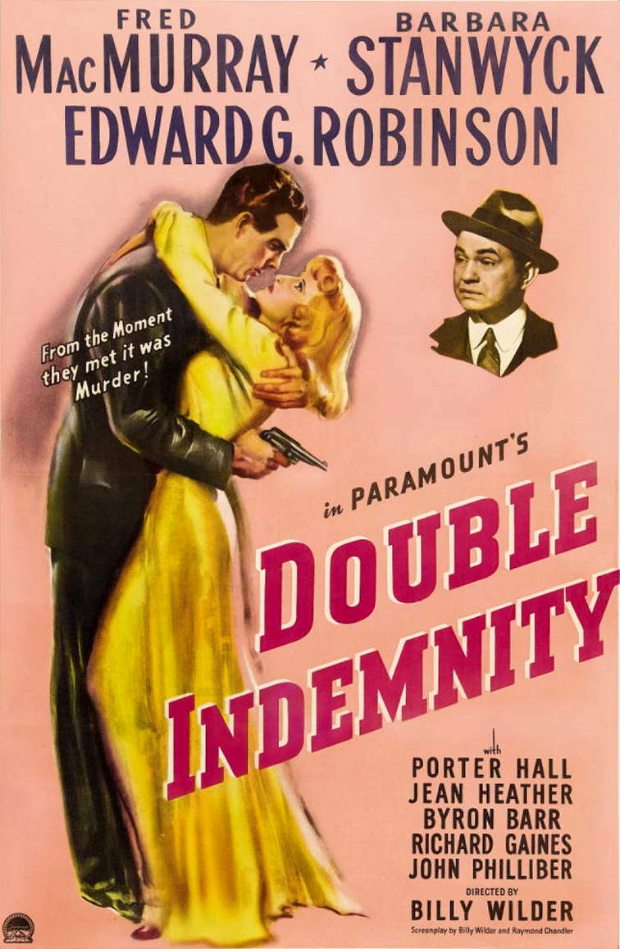

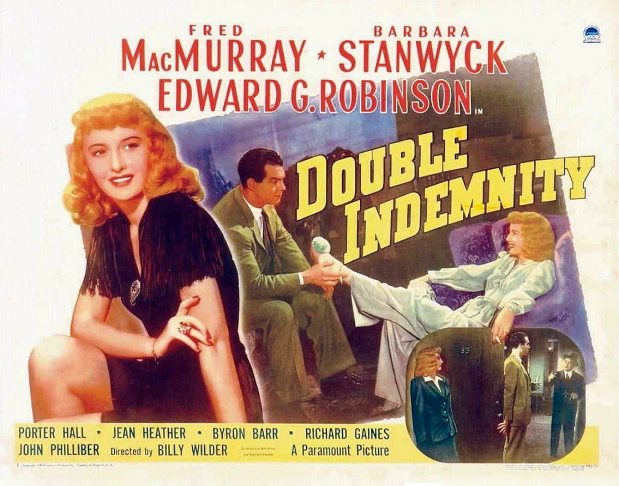

There are, in addition, many films, like Leave Her To Heaven, which explore the existential anxiety of post-WWII America from different perspectives than the true noir. These films — Double Indemnity is another of them — usually offer sociopathic protagonists whom we find both compelling and repulsive, the attitude we had to the underworld thugs of the 30s crime drama, even though their crimes play out in middle-class homes rather than on the mean streets of a city.

True Noir

In the true noir, we can identify totally with the protagonist — not least in his fated doom, or provisional salvation, in a world that has gone terribly wrong, for reasons that aren’t clear and that it probably wouldn’t help much to understand.