. . . to think about Gloria Grahame.

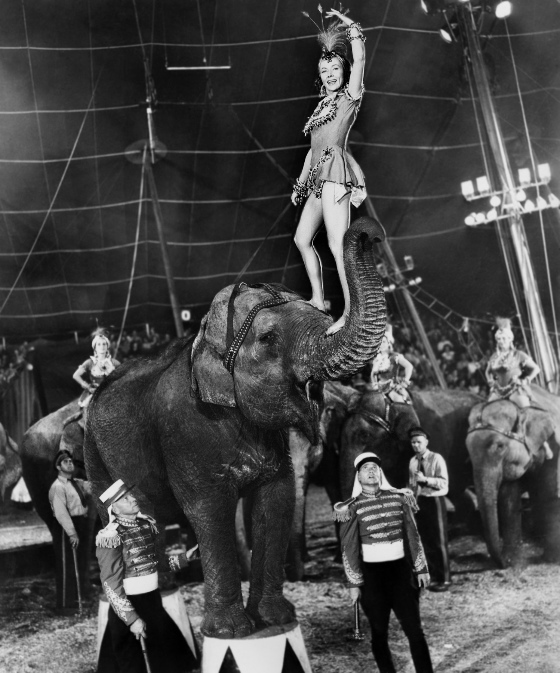

Sometimes it's nice to think about Gloria Grahame standing on top of an elephant.

. . . to think about Gloria Grahame.

Sometimes it's nice to think about Gloria Grahame standing on top of an elephant.

Kierkegaard once remarked that many of the greatest human virtues, like loyalty and faithfulness over time, are almost impossible to dramatize, which is why there are legions of great dramas about adultery but hardly any about good marriages.

A drama about a good marriage has to deal with subtleties, with crises that don’t lead to disaster, with everyday acts of love that don’t erupt into shattering passion.

And yet . . . is there anything more suspenseful than a good marriage? Is there any murder mystery more intricate than the process of accomodation, of creative sympathy and adjustment which keeps a good marriage alive?

Fred Zinneman’s The Sundowners, from 1960, is a movie about a good marriage — about the accumulation of small dramas, never quite reaching a climax, never quite being resolved, that hide within the miracle of a good marriage.

Set in Australia in the 1920s, it’s about a family of itinerant sheep drovers. It’s filled with spectacular location photography and has a few suspenseful action sequences, but at its

heart are a hundred and one things that don’t go wrong, when they should. The father and mother of a teenage son who make up the family don’t change in the course of the film — they have no “arc”, to use a bit of terminology from modern Hollywood storytelling, which turns

characters into geometrical shapes. We just watch scene after scene in which they struggle to remain who they are — two married people deeply in love with each other, deeply committed to each other.

We watch the compromises they make, their acts of forgiveness, their miraculous triumphs of sympathy and empathy, their well-worn joy in each other.

Then suddenly . . . nothing happens. They endure.

As the couple, Robert Mitchum and Deborah Kerr give miraculous performances, quiet and understated — you need to watch them carefully to see the deep currents flowing between them . . . but they’re there, especially in their bedroom talk, where you get glimpses of a grown-up sexuality that mainstream filmmakers rarely portray, probably because they’ve never gotten closer to it than passing a copy of Anna Karenin on their way through a Barnes and Noble bookstore.

The Sundowners may not be great drama, but it’s spiritually exhilarating — something more than drama, perhaps.

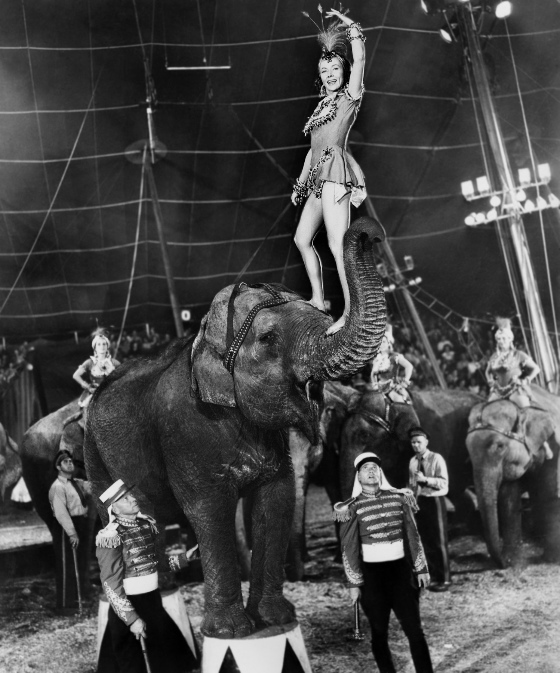

Nicholas Ray's On Dangerous Ground is a problematic film noir on many grounds but in an odd way it helps define the genre. More precisely, it helps us realize that film noir

isn't really a genre at all but a way of identifying a particular

strain of post-WWII dread as it came to infect many different kinds of

film.

This strain was characterized by a sense that the world had gone

hopelessly wrong, that existing paradigms for male identity were

suddenly useless in terms of setting anything right, that women, faced

with the existential nullity of men, were sudddenly in a position to

destroy them at will.

It's this profound and comprehensive existential dread that distinguishes film noir

from the dark pulp fiction of the Thirties, which investigated the

corruption of American society through the eyes of cynical but

personally incorruptible men like Chandler's Phillip Marlowe, or the

crime thrillers which gave us glimpses of the underworld while still

positing forces which could combat and contain it.

These popular forms took us on a tour of the wild side, the dark side of American culture, but the film noir suggested that there was no other side.

On Dangerous Ground violates every standard rule of Hollywood storytelling, and eventually most rules of the noir

tradition. The dream logic that propels the narratives of all

great suspense thrillers is stretched beyond conventional bounds —

just as in dreams sometimes incidents occur which make us realize, even

in the middle of the dream, that we must be dreaming.

Robert Ryan plays a cop on the edge of a total breakdown, overcome by

the sheer meanness of streets which can't be policed effectively except

by adopting the rules of the bad guys. For his own good he's sent

out to a rural community to help with a murder investigation, but

there's nothing redemptive about the country he enters. Bleak,

snow-covered, peopled by vicious, suspicious, isolated farm-dwellers,

it's just as soul-killing as the city he's left. It reminds one

of the landscape of Bergman's Winter Light — a place where the soul shrivels and dies.

But then he meets a woman, played by Ida Lupino — not the traditional femme fatale who waits to ensnare and destroy lost men in many films noirs

. . . but a blind woman paradoxically attracted by his distant,

unengaged treatment of her. His failure to pity or patronize her

gives her a sense of power, encourages her to trust him,

irrationally. And that trust saves him, gives his existence some

meaning.

The film, made at RKO, was much meddled with by studio head Howard

Hughes, which may account in part for its disjointed tone. Ray

disowned the film in later years, saying that Ryan's redemption

involved a miracle and that he didn't believe in miracles.

But the film believes in this particular miracle, and that's all that

counts. And even the miracle fails to violate entirely the dark

vision of the film noir,

since it presents us with a love that's possible only because both

partners in it are disabled, outsiders, in touch finally with their own

despair because they're able to recognize it in each other.

You could call it a religious film — and you wouldn't be far wrong.

. . . to think about Marilyn Monroe.

Film noir

is sometimes used as a catch-all phrase to designate any film from the

1940s or 1950s which has moody black-and-white photography, snappy,

cynical dialogue and some sort of crime element in its plot. In

the process, the term becomes too vague to be really useful.

Gritty underworld crime dramas have been with us since the early silent

era, as has moody expressionistic cinematography, and the private-eye

murder mysteries of the early 40s had plenty of snappy, cynical

dialogue. But the true film noir

didn't emerge until after WWII and it brought something new to

Hollywood cinema — a comprehensive vision of the modern world as a

dark, hopeless place, morally compromised at its core.

Underworld crime dramas could be dark, but they always imagined forces

of order and decency ready to do battle with and overcome the forces of

chaos and destruction. The private eye, for all his cynical talk,

had a kind of nobility and honor that he carried with him into the

shadowy realms in pursuit of truth and rough justice.

Traditional crime dramas and police or agency procedurals continued on

into the post-war era, as did murder mysteries, and though they became

inflected with the atmosphere of true films noirs they didn't stake out quite the same territory.

Laura, made during WWII, is

one of the most stylish and diverting entertainments ever concocted in

Hollywood, and it's regularly classed as an early film noir

— but it's nothing of the kind. The film believes in romance and

love, in the triumph of justice and the possibility of knowing the

truth about things. In a genuine film noir this sort of faith has been lost.

Still, one can see themes emerging in Laura which will play out more forcefully in film noir.

Laura, the film's title character, is an unusually strong and

self-reliant woman, emotionally and financially independent. She

destroys a weak man who loves her but can't win her — as does the femme fatale of the post-war noir

tradition. But Laura's strength is seen as a positive thing here,

not as an insidious threat, and there's a red-blooded man on the scene

who can match her strength.

In the post-war noir,

something goes wrong with the whole idea of the red-blooded man, who suddenly

seems inadequate to the task of engaging a corrupt world or matching

the strength of a self-possessed woman. The world, and desire

itself, come to seem like streets that dead-end in disaster and

oblivion. Some lines from Two Noble Kinsmen, probably by Shakespeare, who co-wrote the play with John Fletcher, anticipate the realm of the film noir nicely:

This world's a city full of straying streets,

And death's the market-place where each one meets.

The amazing object above is an 18″ statuette of the Bride Of Frankenstein made by Sideshow Collectibles.

Sideshow

started out as a model and miniature shop for the film business, with a

sideline in design and sculpting for toy companies. Back in the late 90s, Sideshow

decided it could make better toys, and have more fun, if it got into manufacturing and

so started its own line of 8″ figures of characters from the classic Universal

horror films.

My sister,

shopping for toys for her kids one day, ran into the really

extraordinary 8″ figure they made based on the monster from The Son Of

Frankenstein. She thought I would like it and bought me

one. I loved it — thought it was head and shoulders above other

Universal figures I'd seen, with its first-rate sculpting and its

attention to details in the acccessories. It became one of my

prize possessions — one of my penates, my household gods.

A lot of other

people felt the same way — the 8″ line sold incredibly well and

inspired the company to get more ambitious. I'd checked out the

other 8″ Universal figures but only really liked the bride from The Bride Of Frankenstein. The first 12″ Sideshow figure I saw blew me away, though — Lon Chaney's Erik, from The Phantom Of the Opera,

in his Masque of the Red Death costume. (See it here.) It

remains one of the greatest 12″ action figures of all time.

Again, it was my sister who discovered it and bought it for me.

Tragically, I discovered that almost everything Sideshow produced in

the 12″ format was brilliant. I started collecting them

feverishly. They would sell out quickly in retail establishments

and on Sideshow's web site, so I had to track many down on eBay.

The success of the 12″ line, which came to include historical

figures as well as characters from TV shows, led Sideshow to up the

ante again with their 18″ line. These were not fully articulated

action figures. Sometimes they had slightly posable wire

armatures, sometimes they were cast fully in polystone. The best

of them — like the vampire from Murnau's Nosferatu — were real works of art.

They were so expensive that, sadly, I had to get more

selective. I couldn't resist the 18″ Bride, figure, though.

She's just amazing.

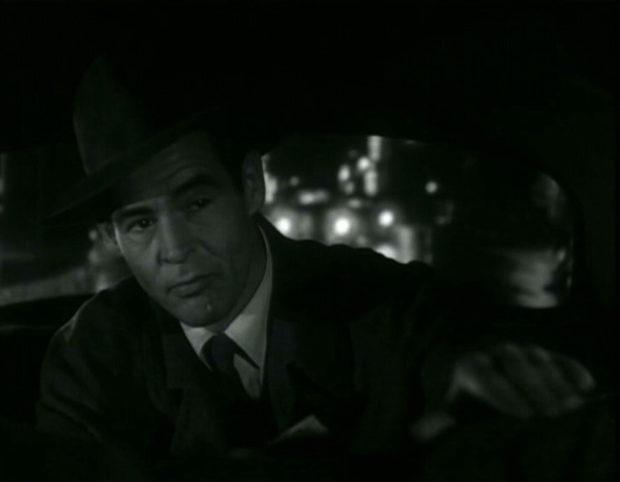

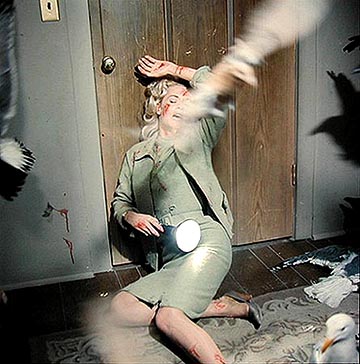

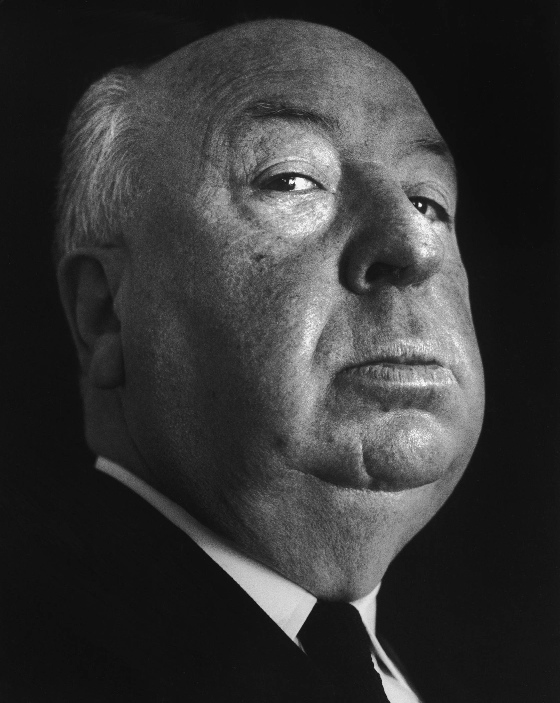

“Space is like an opaque medium that Hitchcock knows how to carve, trim and slice as if it were a side of beef.”

This is from Paglia's book-length essay on The Birds

— and what she says of Hitchcock is true of all the great directors,

who carve up and reshape space before our eyes, drawing us ever deeper into the

spatial illusion of the cinematic image, the core of its sensual appeal and the

primary medium of its emotional expressiveness. This malleability

of space, its ability to be carved and reshaped in cinema, is what places cinema squarely among the plastic arts.

It's a hard concept to grasp, which is why film is traditionally

analyzed in terminology derived from the visual arts, like painting, or

the literary arts, like theater and the novel, even though its most

powerful effects more closely resemble those of sculpture, architecture

and dance. Albert Einstein said, “Space is not merely a

background for events, but possesses an autonomous structure.”

Film does not simply create occasions for visual or literary events — it investigates the structure

of space, associates the structure of space with the structure of

dreams. Orson Welles said that on some level every great film is a chase — which is

just another way of saying that on some level every great film is about space.

[Paglia's short book on The Birds,

published as part of the BFI Film Classics series, doesn't, to me, get

at the heart of the film's themes, but it's an exhilarating

intellectual tour de force

with a dazzling range of allusions to other works of art and to the

cultural matrix from which the film emerged. It's an

indispensable text.]

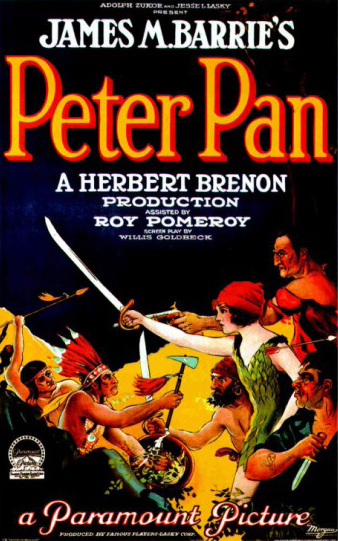

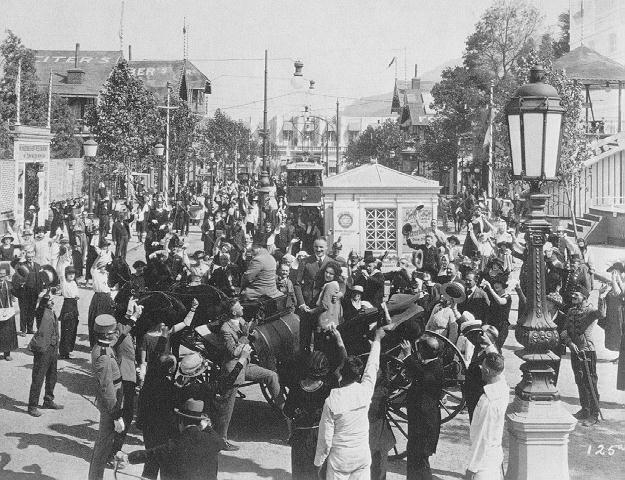

The first half hour of Herbert Brennon’s Peter Pan is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking, masterful in a delicate and unusual way.

Almost all of it takes place in the Darling nursery, on a set that is shot

from basically one angle and seems designed to suggest a theatrical

stage. I’m guessing that this was a deliberate strategy, meant to

associate the film with the celebrated stage productions of Barrie’s

play, even though it was somewhat anachronistic for a film from 1924. Brennon,

however, has taken this limitation as a challenge, and in his own

subtle way has mastered it.

The long shots of the set, with a frame that seems to mimic a proscenium

arch, are lit with extraordinary care by James Wong Howe. He achieves a

stunning impression of depth in the way his lights define discrete

spaces within the room and sculpt individual figures within those

spaces. Brennon’s choreography of movement within the constricted

location reinforces the stereometric nature of Howe’s lighting.

Slowly, and with great subtlety, Brennon allows his camera to tentatively

explore this space from slightly different angles — almost like a

tease. We never feel that our general sense of watching a stage play is

challenged — but seem suddenly, briefly transported up onto the stage

for a privileged view of the action, as in a dream.

The lighting shifts progressively throughout the sequence in a decidedly

expressionistic way — from the high illumination of the opening to the

more atmospheric shadows of the room lit by the nightlights. Then Peter

appears, and the gears shift radically. Wendy sews Peter’s shadow back

on in a gorgeous half-silhouette downstage, then Peter dances with his

shadow in a circle of light, shot from slightly above, that seems to

have no logical source.

When Peter teaches the Darling children to fly, our head-on view of the set

is explicitly violated as we see one of the boys flying up towards a

camera placed near the ceiling and shooting in a near-reverse angle to

the one we’ve mostly been watching from. It’s a shocking and magical

shift — echoing the shock and magic of the child’s first flight.

Alas, the rest of the film, in Never Land, is not as magical as this first

act. The Catalina locations, the studio forest and underground lair,

the actors in animal costumes and the actors in human costumes never

quite cohere into a vision, despite many delightful passages. The final

action sequence on the pirate ship is confused and dull — until the

wondrously choreographed sword battle between the Lost Boys and the

pirates lifts it all into magic once again.

The special effects vary in quality, too. Most of the wire-work flying is

well done, but the flight of the pirate ship at the end is

underwhelming, and some of the superimpositions involving Tinkerbell

are poorly executed.

This is a title-heavy film, but the titles are faithful to Barrie’s truly

charming text, tastefully selected and arranged.

The general result is a very uneven but endlessly fascinating film.

Brennon’s vaguely perverse sensibility, always delivered with a

gossamer touch, is evident most especially in his use and appreciation

of Betty Bronson in the title role. She dances the part in a frankly

sensual way, and she is unmistakably and delightfully female — which

allows Brennon to exploit an unmentionable eroticism in certain

passages.

The half-silhouetted shadow-sewing sequence between Wendy and

Peter has the quality of a sexual encounter, and there is nothing

innocent in the numerous kissing scenes — between Bronson and Mary Brian,

Bronson and Anna Mae Wong, Bronson and Esther Ralston.

When Peter lies down to sleep on the leaf bed after Wendy and the Lost Boys have left the underground lair, Bronson is photographed in a languorous and sensual and purely

feminine pose — which gives Captain Hook’s spying on her a wholly different spin than the narrative might suggest. Hook’s hatred of Peter reads as thwarted lust, pure and simple. He knows as well as we do that the creature on that bed is a woman.

Sex in silent movies was a lot more interesting than it is in movies today.

Mexico has always had a peculiar place in the popular American imagination.

It has generally tended to represent a kind of mirror world where the

subconscious could emerge into the light — where desire, fear, death, despair, escape from responsibility and propriety could show themselves plainly.

There is chauvinism involved here, of course, a sense of Mexico as a

primitive country, but also an appreciation of the positive genius of Mexican

culture, its sensuality, its frank engagement with death and violence,

with things that the official culture of America prefers to keep hidden

in the shadows.

WWII exposed those hidden things for a generation of Americans and in its wake film noir began a systematic investigation of the shadow world at the fringes

(and somehow also at the heart) of American culture. In the

process, Mexico took on a new aura. It became a kind of shimmering

paradise, the locus of an honesty and innocence that no longer seemed

feasible along the mean streets and lost highways of post-WWII America.

So in Out Of the Past, Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer live out a doomed idyll in Mexico, on the run from a gangster who has his hooks into both of them. When they try to carry that idyll north of the border, integrate it into a new life there, they’re both destroyed.

In Border Incident, decent Mexican peasants are exploited and sometimes murdered by powerful American businessmen north of the border who traffic illegally in their labor. (Border Incident, while it deals with a number of themes from classic film noir, departs from the tradition by positing good-guy government agents as saviors of the peasants, thus violating the cosmic cynicism and skepticism of the true film noir.)

In Gun Crazy, the young couple possessed by a mad love, a love fuelled by irrational violence, are just a few hours away from a safe passage over the border when their crimes catch up with them and send them on a final hopeless flight from retribution and death.

The nuttiest use of Mexico in film noir can be found in what may be the nuttiest of all films noirs, His Kind Of Woman. The movie starts off fairly traditionally, with Robert Mitchum as a down-on-his-luck gambler who’s hustled into taking a mysterious job south of the border. As soon as he arrives in Mexico it’s like he’s gone to Oz. He walks into a dingy cantina about the size of a phone booth and in a back room, about half the size of a phone booth, he finds Jane Russell singing Five Little Miles From San Berdoo accompanied by two Mexican musicians doing cool jazz riffs on guitar and piano. Things get so nutty after that that the whole noir genre is pretty much deconstructed by the time it’s all over.

As film noir played itself out in the 50s, the image of Mexico in American art shifted back to a more familiar form. In the Tennessee Williams play The Night Of the Iguana (and in John Huston’s film adaptation of it), in Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head Of Alfredo Garcia, in Huston’s film of Under the Vocano, Mexico became once more a portal of Hell, where lost American souls went to confront their demons — in an unequal contest which the demons were always fated to win.

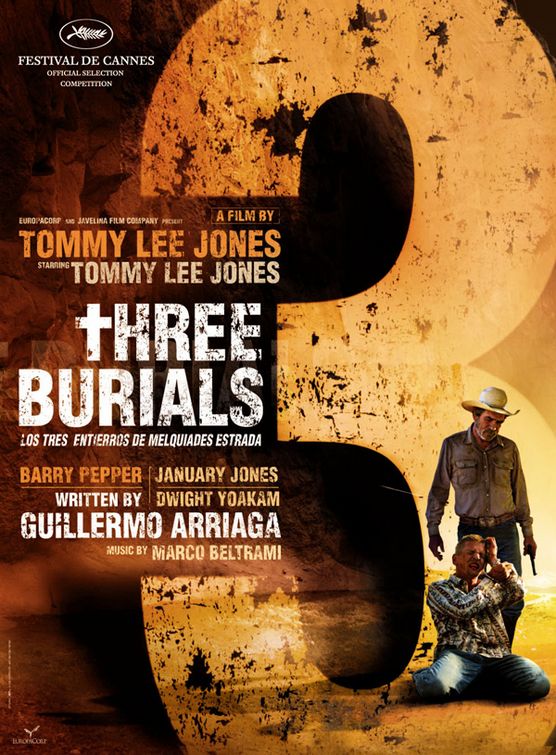

In the light of this peculiar history, it’s interesting to look at a recent film, the post-modern film noir The Three Burials Of Melquiades Estrada. There another troubled American soul heads south of the border on a quest for a lost paradise — only to discover that the paradise wasn’t really lost because it never really existed. And it doesn’t matter. We realize by the end that the quest itself has redeemed and saved him. The film was written by a Mexican, who knows that Mexico is neither Paradise nor Hell . . . except in the dreams of lost souls on both sides of the line.

[For more thoughts on Mexico and film noir go here.]

Actually, this is Carlyle (pictured below) on Dickens, but the application to Hitchcock is clear enough:

“. . . deeper than all, if one has the eye to see deep enough, dark,

fateful, silent elements, tragical to look upon, and hiding amid

dazzling radiances as of the sun, the elements of death itself.”

Dickens and Hitchcock both hid within the conventions of popular art,

and one misses a lot, one misses close to everything, if one takes

their disguises too literally.

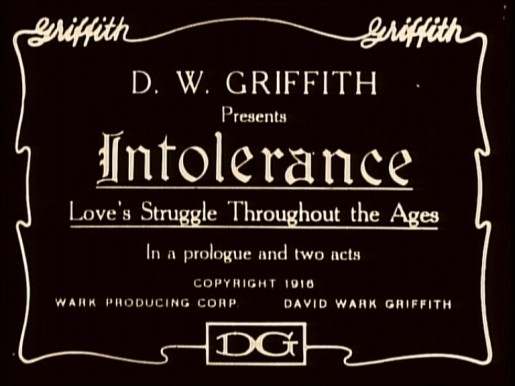

In order to enjoy and appreciate Intolerance you have to watch it the

way you read Dickens — submitting to its rhythms, surrendering to its

asides and narrative diversions. You simply can’t be too

impatient to find out what happens next in the story (or

stories.) Dickens and Griffith are more interested in how things

happen, where things happen, to whom things happen. There’s no

shortage of fascinating incident in either artist’s work, and much of

it is spectacular — but sometimes the incidents are very small indeed,

and no less fascinating for that.

I’ve seen Intolerance many times, and I find I remember small gestures and

glances, brief passages of body language with the same vividness that I

remember great lines of dialogue from talking films. The flirty

and then dismissive looks the girl outside the dance hall gives the

mill owner Jenkins who’s come to spy on his workers make for an

indelible moment — involving a bit player we never see again.

The Mountain Girl’s postures of energy and defiance look in retrospect

like a primer on flapper attitude, years before the flapper even

existed.

It takes Griffith over half an hour to introduce us to all four of the time

periods covered in the film. We start in the modern story,

proceed to the time of Jesus, then to 16th-Century France — then back

to the modern story before seeing the walls of Babylon for the first

time.

Almost every image in this first half hour is stunning, worth studying for its

dynamic composition involving movement and deep space. The illusion of

depth draws us emotionally into the film just as surely as the

interwoven narratives and the performances.

This effect is most powerful on a big screen, of course, but it’s effective enough on

a decent-sized TV monitor. When you consider a video screen’s

tendency to flatten any image, it’s all the more amazing that

Griffith’s images retain their stereometric brilliance in that format.

One great virtue of the DVD format is that it allows one to watch (or, one hopes,

re-watch) a film like Intolerance in segments — which is the way one

reads those long Victorian novels originally published serially.

The film reveals much when experienced this way. There’s almost

no chance in any continuous viewing of the three-plus hours of Intolerance that one could sustain the intensity of attention needed

to fully absorb its torrent of beautiful images in detail.

If you have Intolerance on DVD, go watch just its first half hour — to the end

of the first Babylonian segment. There’s enough cinematic

brilliance in that half hour to justify, by itself, the whole medium of

movies.

[If you don’t have Intolerance on DVD rush out and get it immediately. The

Kino edition is generally considered to have the best image quality.]

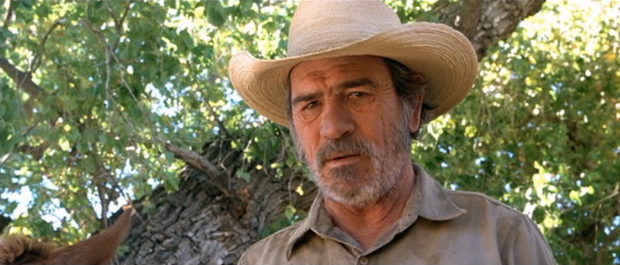

Tommy Lee Jones, one of the great actors of his generation, has, with this

film, become one of the most important contemporary directors.

It’s just miraculous. The wonderful performances by the ensemble

cast and by Jones himself might have been expected — but the brilliant

script and the brilliant filmmaking testify to a sensibility at home within the whole range of cinematic expression.

The sense of place that the film communicates, via Chris Menges’s stunning

cinematography, reminds one of John Ford. Jones, like Ford when

he was shooting in Monument Valley, is working here in a landscape he

clearly loves and knows well. It’s important to him, as it was to

Ford, to make us feel what it’s like to be in and move through that

landscape — and he does.

One notes with particular pleasure Jones’s use of horses in the film. Just watching Jones

sit a horse brings back by itself the whole tradition of the American

Western, in which horses aren’t props but a means of establishing the

authority and conveying the subtler nuances of character. The horses themselves are

given their own moments — all memorable. We see a steady old cow

horse try (successfully) to master its hysteria as a man fires a rifle

next to its head. We see a horse react emotionally as another

horse rides off into the distance — violating the compact of the herd

instinct. It reminds me a bit of Tolstoy, another serious

horsebacker, who always lets you know how the horses in his scenes are

feeling.

The tale Jones tells, written by Guillermo Arriaga, the author of Amores Perros, is

dark, comic and moving. It’s set on the Texas border and asks us

to travel imaginatively backwards on the route of the illegal

immigrants — to enter into the memories and dreams the immigrants leave

behind, and so see them more fully as human beings, as opposed to mere

statistics.

The tale is inflected with the sardonic, broadly comic Mexican view of death — Posada’s calaveras ride with Jones here — and the film’s visuals reflect the bold colliding colors of Mexican folk art, all blended seamlessly with the shabby commercialism of American

culture that also defines the world of the border lands — what Carlos

Fuentes calls Mexamerica, in many respects a nation unto itself, which

no wall will ever cut in half, just as no wall could ever really cut Germany

in half.

As in Ford’s great films, the landscape itself finally subsumes human contradiction

and tragedy — infuses a sense of transcendence which expresses itself

as hope. Irrational gringo optimism and sardonic Mexican resignation transform each

other, merge into one deeply humane vision.

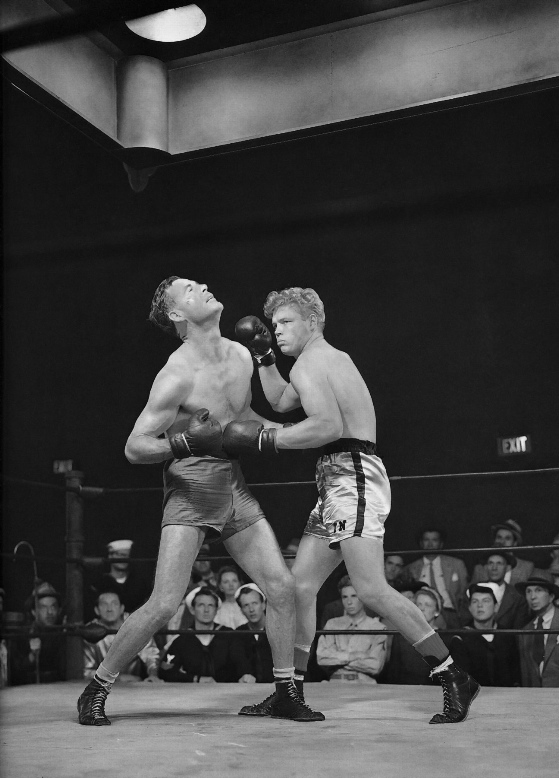

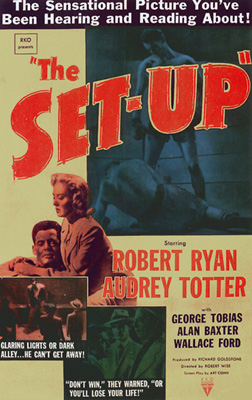

The Set-Up, a classic film noir directed by Robert Wise in 1949, couldn't be more different in many ways from Jacques Tourneur's equally admired classic noir Out Of the Past. For one thing, The Set-Up doesn't have a femme fatale. There's no romance, no glamor, no witty hardboiled repartée. But if you realize that classic film noir is centrally concerned with anxiety and neurosis about manhood, the two films fit neatly together in the noir tradition.

The Set-Up

is about the boxing underworld, the tank-town circuit where

up-and-comers get their chops and has-beens rent themselves out as

human punching bags. Robert Ryan plays a has-been, a

once-promising fighter who's come to the end of the line. His métier is perhaps the most iconic arena for displays of traditional virility — his exhaustion a sharp symbol of its decline.

The fans jeer him. His own manager takes money to get him to take

a dive but doesn't even bother to inform him, so sure is he that his

fighter is going to lose . . . one more time. Ryan's

long-suffering wife is about to walk out on him, unable any longer to

watch his steady and inexorable collapse. Ryan's continued belief

in himself as a fighter is presented as the delusion of a punch-drunk

loser.

But Ryan still has one more victory in him, one last assertion of his

potency in the ring. The victory, however, is no triumph.

His wife hasn't even come to the arena to watch it. His corner

men flee before the fight is over. The manager of the fighter he

was unknowingly paid to lose to sets his thugs on him and beats him up

in an alley, smashing his hand so he can never fight again.

In a powerful sequence just before the assault in the alley, Ryan runs

through the empty arena, past the empty ring, trying to escape.

His ritual of manhood has become a shadowplay that nobody cares about,

nobody's watching.

The Set-Up

plays out in real time over the course of one night, creating an almost

unendurable suspense. The four rounds of boxing shown, again in

real time, are the best evocation of a real fight ever put on

film. The high-speed meta-narrative that always develops in a real fight,

especially a good one, is both complex and legible, and the combat is

convincingly brutal. (Ryan was a champion fighter at the college

level and knew what he was doing.)

The ending of the film is satisfying because of the heroism involved in

Ryan's last stand — even though it's meaningless in practical

terms. It's sort of a glorious farewell to his own construction

of himself as a man. His wife is still there for him, happy that

he's been forced to move on. But move on to what?

Film noir never had an answer

to that question, and the resulting tension is what has always constituted the

deep subliminal appeal of the genre. It posed a question that

modern men are still asking themselves.

Well,

not precisely, but this quote by Eliot about poetry offers a key to

analyzing Hitchcock's films, and, indeed, all great suspense thrillers:

“The chief use of the ‘meaning’ of a poem, in the ordinary sense, may

be . . . to satisfy

one habit of the reader, to keep his mind diverted and quiet, while the

poem does its work upon him: much as the imaginary burglar is always

provided with a bit of nice meat for the house-dog.”

In Hitchcock's movies, the plot mechanics, the mystery to be solved, the suspense engendered

by the nominal physical jeopardy of the characters — all this belongs

to the territory of the “maguffin”, the essentially arbitrary device

that sets the narrative in motion.

The truth of the film is experienced on another level — which is one

reason it's so enjoyable to watch Hitchcock's movies over and over

again, why they always seem new. You forget the plot mechanics instantly —

they don't linger in the mind for even a moment after the film is over. All you're

left with is the memory of confronting, and surviving, some nameless,

existential dread.

[I am indebted to Ken Mogg's The Alfred Hitchcock Story for pointing me towards the Eliot quote and suggesting its connection to the Hitchcock maguffin. The Alfred Hitchcock Story

is a pictorial survey of Hitchcock's films with pithy commentary by

Mogg and other Hitchcock experts. It's worth tracking down the

British edition, published by Titan Books, since the American

edition is unfortunately and unaccountably abridged.]

Erich Von Stroheim was above all else a wondrous spinner of tales. His

storytelling mode was, at heart, melodrama, but much modified from its

conventional forms. He embraced all the sensational elements of melodrama, its

reliance on wild coincidence and its stark dynamic of good versus evil

but subverted them to his own ends. He made the erotic subtext of much

melodrama explicit, he used coincidence to serve his own fatalistic

vision of human destiny, and he inverted expectations about protagonist

and antagonist, making the former often weak and foolish and the latter

invariably fascinating and appealing, especially when he himself played

the role.

His

vision of the world was brutal and harsh, but he preserved the romance

and the celebration of virtue at melodrama's core — in the form of his

faith in a pure and spiritual love which could transcend the vagaries

of fate, even if his version of such love often existed outside the

realms of strict propriety.

He was

a popular artist of his time, speaking to audiences in a language they

could understand, even as he extended the expressive and thematic range

of that language. Of the seven films he completed only three were

released to the public in versions close to what he intended, and all

three made money — quite a lot of money. Von Stroheim knew his public

and its taste, and we err when we accept too quickly the judgment of

the studio executives who decided that this public would not have

accepted his four mutilated films in the longer versions he originally

prepared. We will never know for sure, of course, but it's an insult to

a popular artist of Von Stroheim's stature and achievement not to give

him the benefit of the doubt on this score and to accept uncritically

the verdict of the creative mediocrities who vandalized his films.

The

tale Von Stroheim concocted for what would have been his fourth film, Merry-Go-Round, is perhaps his most romantic — inspired as it was by

his nostalgia for the old Vienna he grew up in, the one that vanished

forever in the catastrophe of WWI. Von Stroheim's participation in this

old Vienna was not what he claimed it to have been — it was part of

his dream world from the start — but it was at the center of his

imaginative life and he seems to have felt its loss just as keenly as

(perhaps more keenly than) the loss of something real.

In Merry-Go-Round, Agnes becomes a symbol of the innocence and allure of

the dream of old Vienna — one which redeems the deceitful and

hypocritical Count Hohenegg, and by extension the whole corrupt

superstructure of the Hapsburg fantasy. That fantasy was worthwhile,

Von Stroheim seems to say, if it could make a place for dreamy,

waltz-inflected nights at the Prater, and for Agnes, the sweet

incarnation of those lyrical interludes.

When

we think of dreamlike films, or dream sequences within films, we might

be tempted to think of the expressionistic style filmmakers often use

to signal a dream state — but of course real dreams do not present

themselves in that way. We might, in a dream, find ourselves at home

and discover a previously unnoticed door opening onto a previously

unsuspected wing of the house — but that wing is not appointed like

the cabinet of Dr. Caligari . . . it is as convincingly real a place,

in the dream, as the actual house we know.

Von

Stroheim appropriated this aspect of actual dreams to give his

cinematic universe the power of the dream spaces we concoct, with a

similar attention to detail, in our sleep. This was Von Stroheim's way

of seducing us into his dreams, making us take them seriously. It was a

storyteller's strategy — not, as has often been suggested, some kind

of neurotic obsession with “realism”, much less an egotistical

extravagance. While Von Stroheim was obsessing over his “extravagant”

sets he himself lived in an exceedingly modest home in Hollywood, and

led a mostly mundane and largely domestic private life.

Von

Stroheim was the first great director to realize consciously that

movies alone could use this illusion of a coherent and convincing dream

universe to give power and depth and weight and resonance to an

ordinary tale, to overwhelm us with the subliminal power of an actual

dream.

Von

Stroheim was fired from Merry-Go-Round somewhere between a quarter

and a third into the shooting. The story was rewritten and the shooting

completed by Rupert Julian, a studio hack appointed by the dazzlingly

mediocre producer Irving Thalberg. Enough remains of Von Stroheim's

vision to show us what the film might have been — and there is more

than enough of Julian's work on display to make the genius of Von

Stroheim's method stand out in stark contrast.

Julian's

mise-en-scène is theatrical and uninventive, without a trace of plastic

imagination. He does not place us inside a dream universe but at the

edge of a stage. We don't have the sense of being someplace but of looking at something. Julian also encourages his actors to act — in an

exaggerated theatrical style that several of them had no training or

capacity for, and that violates in all cases the more naturalistic and

engaging style Von Stroheim knew how to elicit even from novices.

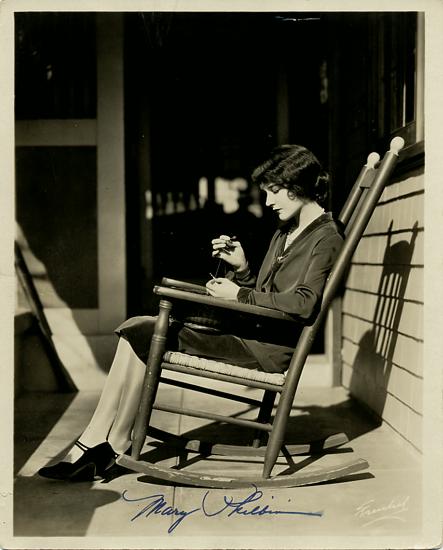

Despite

all that, the performances of Norman Kerry and Mary Philbin are

revelations. Kerry was playing his first important role here, and

Philbin her first role of any kind (apart from a walk-on in Foolish

Wives.) Kerry was a small-time actor whom Von Stroheim here elevated

to star status — and we can see in his performance what Von Stroheim

saw in him. He's sort of like a laid-back, less boyish John Gilbert,

with tremendous masculine authority, which seems utterly natural and

utterly appealing in those scenes directed or influenced by Von

Stroheim but which vanishes entirely in those scenes in which he is

called upon to emote in a more conventional (though already

anachronistic) style.

Philbin

was an actual discovery of Von Stroheim's — he'd named her as the

winner of a publicity-stunt beauty contest he judged in Chicago. She

has real charm and power in Merry-Go-Round, and also a totally

convincing naturalness — except when Julian persuades her to try for

the high style, at which point she seems merely competent. Her

generally undistinguished performance in The Phantom Of the Opera

must be attributed directly to Julian's cluelessness and bad taste as a

director of film actors, because she was an artist of genuine talent

and potential. (The fact that she became one of Universal's biggest

stars in the Twenties is yet more evidence of Von Stroheim's insight

into the popular taste of his time.)

Much

of Von Stroheim's dark vision of human behavior was removed from the

reworked version of the tale given to Julian to execute, which makes

the romantic idealism that triumphs in the end seem a bit saccharine.

Dimwits like Thalberg didn't understand how dark elements could set off

and energize the positive and redemptive themes always present in Von

Stroheim's work.

Universal

called its prestige releases Super-Jewels. The existing version of Merry-Go-Round is a Super-Rhinestone — but in it we can see

reflected a great masterpiece, the film Von Stroheim might have made

without the intervention of Irving Thalberg and his all-too-perfect

alter ego Rupert Julian.