This building, in the small town of Belhaven, North Carolina, used to

be a movie theater, a palace of dreams. It was a tiny palace, as

you can see. The set-back led to doors which opened directly into

the theater — there was no lobby. Popcorn, the only snack sold,

was dispensed from a movable cart set up on the sidewalk just under

the marquee, which is now gone. I made a pilgrimage to the

building this past summer, because it was such an important part of my

life, once upon a time.

In 1956 and 1957 this theater was a few minutes walk from my home, and

I made that walk every Saturday, when the feature film always

changed. A kid’s ticket cost 25 cents, half my allowance, and

popcorn cost 15 cents. A Five and Dime next door sold popcorn for

10 cents, but you had to sneak it into the theater, past the watchful

eyes of a teenage usher. I was five and six years-old in those

years, and I don’t think I ever missed a show.

Here are the ones I remember most clearly:

MOBY DICK

The John Huston version with Gregory Peck. When I looked at the

poster and the lobby cards outside the theater before going in I

wondered if the film could possibly deliver the spectacle it

promised. It did — beyond my wildest anticipation.

THE YEARLING

This movie affected me as deeply as any work of art ever has. It

was really the first work which showed me how powerfully art can move

the heart.

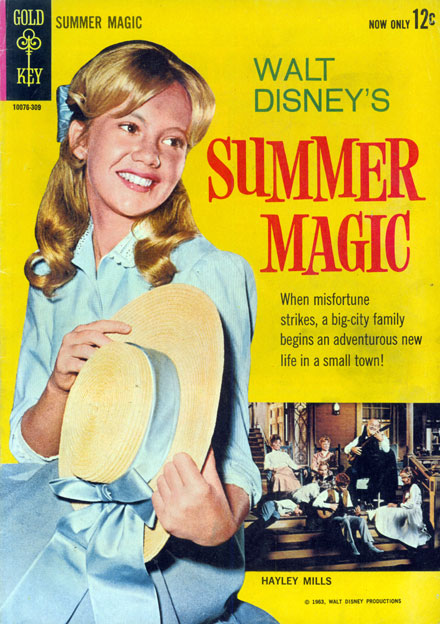

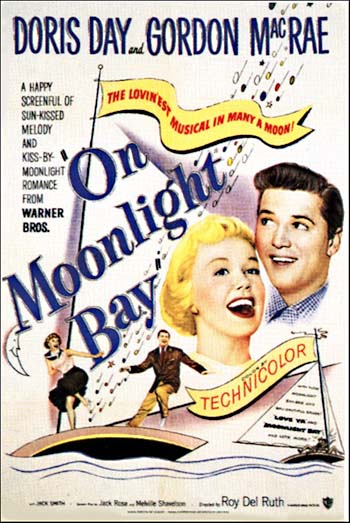

ON MOONLIGHT BAY

I don’t remember this movie very well, though I remember the poster clearly. The song On Moonlight Bay always gets to me, though, and that must have something to do with having heard Doris Day sing it in this film.

THE TEAHOUSE OF THE AUGUST MOON

I don’t remember this one very well, either, and I haven’t seen it

since, but I have the impression that some sort of miracle occurred at

the end of it which was delightful.

JAILHOUSE ROCK

This was the first film I was ever allowed to go see at night without

adult supervision. Our babysitter, a girl in her early teens,

escorted my sister and me and a few neighborhood pals to the

show. The crowd was different at night, older, better behaved,

even for this rock and roll classic. The evening screening seemed

like a window onto another world.

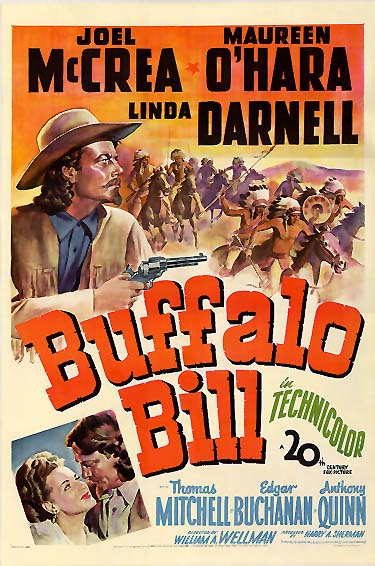

BUFFALO BILL

I only saw the first half of this film because I was suddenly

gripped by a profound sense of homesickness — for a home that was

practically in sight of the theater I was in. When I got back

there I was unaccountably relieved to find my mom in the kitchen — as

though she’d be anywhere else an hour or so before suppertime.

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS

This film did not screen on Saturday, but on a Wednesday afternoon,

when the theater was always dark. I assume this was because it

wasn’t a big enough house to rate a print of the newly released epic,

which was something of a sensation at the time, on a weekend.

(Many of the films I saw in Belhaven were older releases — whatever

prints the theater could get hold of when the new releases were tied up

in bigger towns.) This Wednesday was a school day and I had to get special permission from my second-grade teacher to skip afternoon classes to go see it.

Permission was granted, undoubtedly because of the uplifting nature of

the motion picture in question. No one else in the class wanted

to go see it but me, and there was almost no one else in the theater when it played.

Consequently I felt even more overwhelmed by the spectacle than I might

have otherwise been. It was almost as though the drama was being

played only for me.

The movies I saw at this little palace of dreams have a kind of glow about them, in my memory, which time has never dimmed. Even watching the films again and discovering that they weren’t quite as magical as they seemed back then doesn’t really

alter my memory of them. I saw the films I saw, they were what

they were, and they set the standard of enchantment against which I

measure all other films.