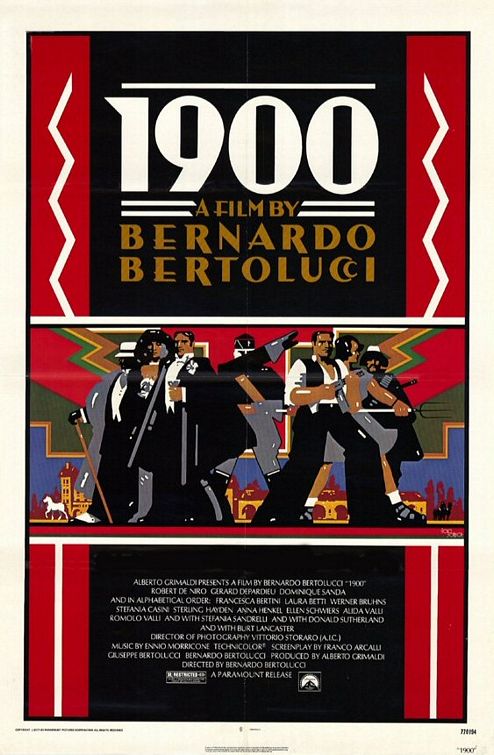

Perhaps the most exciting cinematic event of 2006 was

the release on DVD earlier this month — finally, and in a terrific

transfer — of Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist.

Few films of the post-WWII era have been as

influential as this one — few films of any era have been as ravishing,

as sensually exciting.

In the freewheeling atmosphere of the time, and with

the final collapse of the old studio system, Hollywood in the late

Sixties was in an experimental mood, though the experimentation often

involved only superficial stylistic gimmicks — the hand-held camera,

promiscuous zooming, elliptical editing, split-screen images.

At the same time a new generation of filmmakers was

coming into prominence which had been schooled in, and deeply loved,

the classic Hollywood films — among this generation were

Coppola, Scorsese, Spielberg and Lucas . . . all of them, except for

Spielberg, the products of film schools rather than of apprenticeship

in the industry.

They were tackling new subjects and ones that were often more challenging

than the old studio system could embrace but they were

developing a style that owed much to the formal elegance of the

cinema of the studio era.

Then, in 1970, The Conformist burst onto the scene,

the work of a young Italian filmmaker who had not only mastered the

formal elegance of the old studio style but was taking it into new

realms of expressiveness and invention. Indeed, The Conformist had

something of the visual eloquence of the highest achievements of the

silent era, of Murnau’s and Vidor’s films, whose

extravagant poetic imagery had been lost with the coming of sound.

The effect was electric — confirming all the creative

instincts of the American film-school avant garde. The movie was so

important to Coppola that he, along with a number of other American

directors, personally lobbied its distributor to release the film in

the United States. He used one of its actors in The Godfather, Part

II, and its visual style influenced every frame of Coppola’s

masterpiece.

Bertolucci never made another film quite like it.

His visual imagination, his gift for dynamic plastic composition and

choreography within the frame stayed fresh, but was often lavished on

unworthy material and degenerated into mere mannerism.

The Conformist was of a piece because its story and

its visual style reinforced each other. Bertolucci was, in the film,

breaking dramatically from the severe aesthetic strategies and rigorous

intellectualism of his mentor Godard, indulging himself frankly in the

cinema’s power for sensual seduction — all the while telling the tale

of a promising student who betrays the political ideals of his old

professor and eventually collaborates in the professor’s murder.

The Conformist remains alive with the allure of forbidden

pleasures, tense with the guilt of giving in to them. The film is

erotic but disturbing — a dynamic that Bertolucci would explore

more explicitly in Last Tango In Paris, but without the organic

emotional coherence of the earlier film.

The Conformist also marked the emergence of its

cinematographer Vitorio Storaro as an artist of international

stature — but that’s a subject for a future post . . .