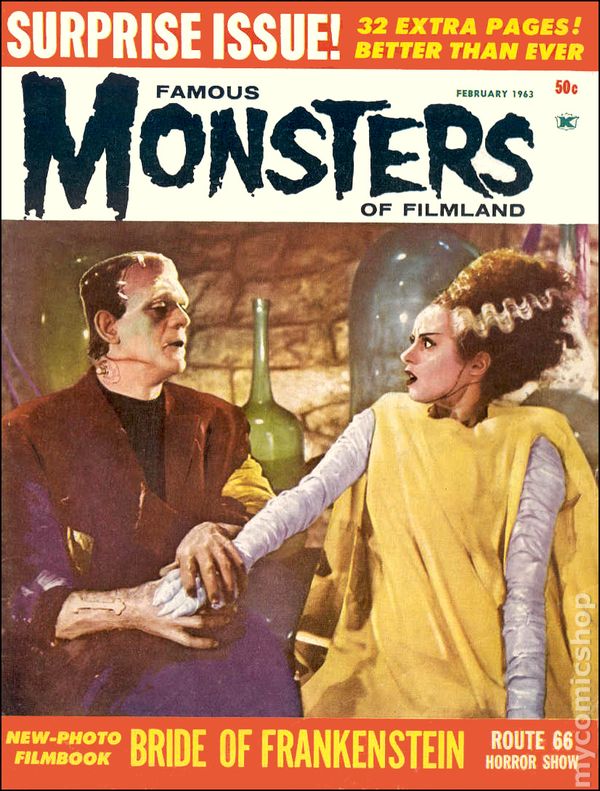

The Bride from Bride Of Frankenstein is my favorite character in any movie. Her few scenes in the film (as a living being) last a bit over four minutes and she speaks no lines — she just screams and hisses a few times, in what Elsa Lanchester, the actress who played her, said was an imitation of a swan’s hiss.

Yet for all that she has become an iconic movie monster, and she continues to fire my imagination, as she has since I first caught sight of her — in a TV broadcast of Bride Of Frankenstein one Saturday night in 1962, when I was 12.

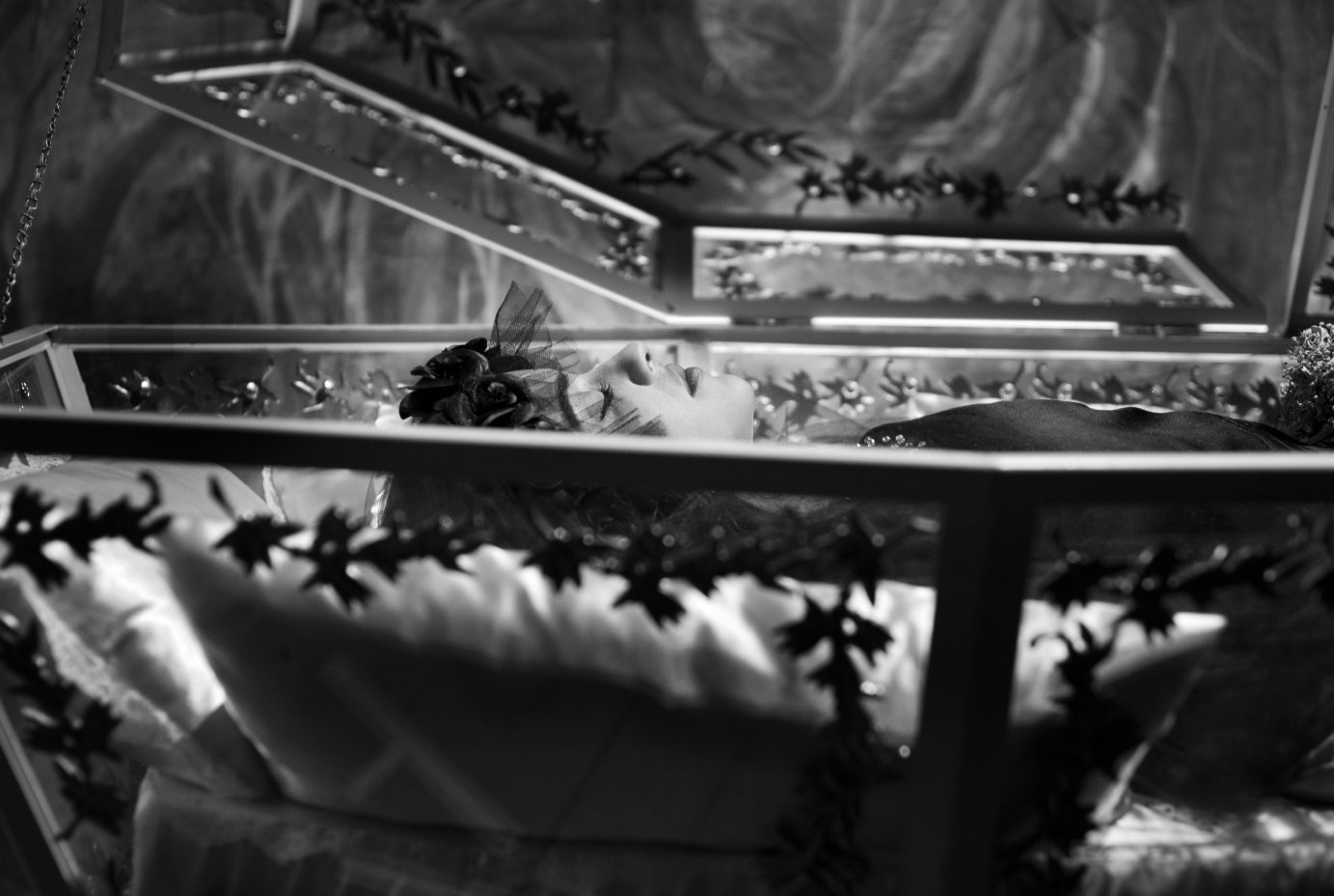

She is of course a creature sewn together from bits and pieces of corpses — a woman of many parts, you might say, a universal woman, but also the nominal creation of men. We see the sort of cadaver she was made from in a scene before she’s been assembled and animated — the cadaver of a beautiful young girl lying in a coffin in an underground crypt.

The Monster has accidentally broken open the top of her coffin and is instantly enchanted. He gazes upon her longingly and speaks the word “friend”. As a sort of animated cadaver himself, feared and mistrusted by regular human beings, he seems to think that only the dead could possibly understand what it’s like to be him.

The serene repose of the girl in the coffin is not what The Monster finds when The Bride, intended as a mate for him, is eventually brought to life. She has the furious energy of an enraged cat, and she doesn’t see herself in him — she sees a monster. As I stood on the precipice of puberty at age 12, starting to think sexually about women for the first time, albeit very vaguely, I suspect I wondered if women might react to me in the same way when the time for romancing them came around. It’s a primal male anxiety.

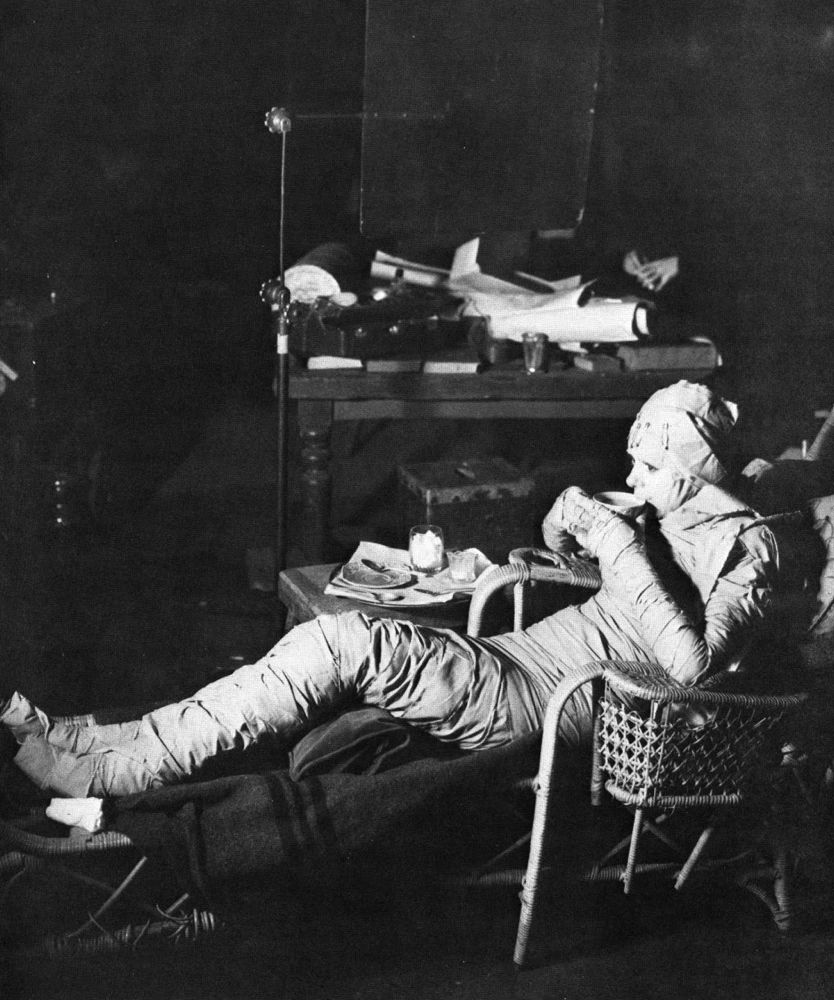

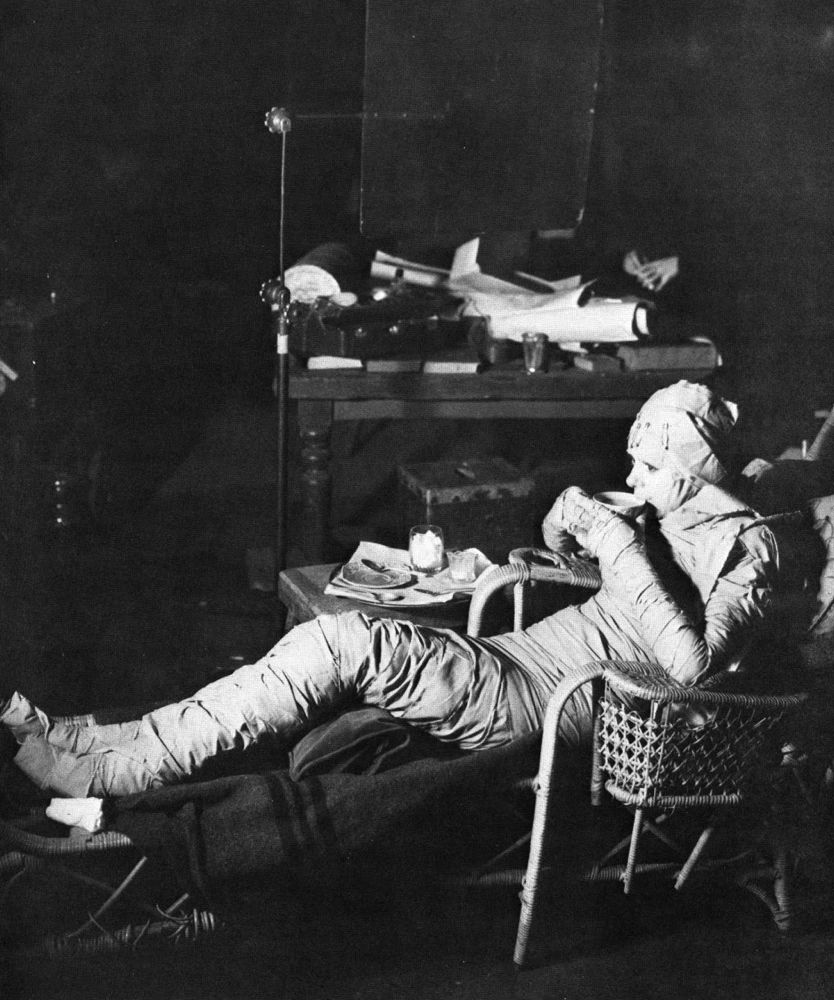

The Bride is anything but a monster herself. We first see her wrapped up like a mummy, with all her delectable curves plain as day. It’s an image of pure womanliness, of all the things that make women different from men physically — but the wrappings suggest her mystery as well, the idea that those curves cannot be possessed directly or easily, that some serious unraveling, both literal and psychic, will be required.

Colette, who knew a lot about sex, once did a music hall act in which she appeared wrapped in linen strips like a mummy and slowly unwound them in a kind of striptease, eventually showing more skin than was considered legally acceptable. It sounds far more erotic, more primal, than a pole dancer flinging off bits and pieces of a conventional costume.

Once The Bride’s head is uncovered and she’s fitted in her long white gown, a cross between a wedding dress and a shroud, we still see the mummy-wraps on her arms and know that she, and her persona, remain shrouded in enigma, however she’s presented cosmetically to the world. She walks in a faltering but somehow graceful way, like a newborn fawn. Her head jerks around as she takes in her surroundings as though it’s still animated by the lightning that brought her to life — her hair shoots out straight behind her, as though an electric charge is still passing through her.

Her face is beautiful, despite the scars on her neck, as beautiful as the face of the girl in the coffin we saw before, but this new girl is shot through with an energy one can’t help but read as erotic. She’s a spitfire, a handful — very other from a male perspective but wildly desirable in a purely carnal way.

She has her own ideas about things, which violate the ideas of the men who made her to mate with The Monster, the desire of The Monster to make her his mate, or at least his friend. She doesn’t want to be friends. Her swan’s hiss is a brilliant stroke, the cry of an elegant bird who’s fighting mad.

It’s all too much for The Monster, and maybe for the filmmakers, too. Where can this character go from here? What man or monster alive could handle her? What in God’s name does she want?

So The Monster throws a lever that destroys the lab where he and his impossible mate were born, killing her and himself. What she might have said about herself if she’d been taught to speak, what she might have become if she’d been given her head — these are questions that cannot now be answered, that The Monster may fear hearing answered.

It has all the makings of a tragedy, but it’s not quite a tragedy — because the image of The Bride endures, haunts the mind. We revisit the scenes of her brief life in the film, and in cinema history, to ponder the secrets she took with her to the grave, to ponder her enigma and her challenge. She remains The Eternal Feminine, in all her power and allure, and she still leads us on . . . but where? And who will speak for her, to tell us?

Click on the images to enlarge.