This is a kind of synthetic folk song, like “Old Man River” — a Tin Pan Alley evocation of the existential laments found in the black musical repertoire. “Synthetic” doesn’t mean phoney — it’s more like a paean to the sublime vernacular expressiveness of the spiritual and blues traditions. You might see it as a form of minstrelsy, in which a white artist wants to say something he or she can’t say in his or her own persona but can say in blackface.

Blackface wasn’t always patronizing — sometimes it facilitated a profound and humble and loving tribute to black style, black culture. The performance history of “That Lucky Old Sun” has transcended racial boundaries. The best versions of the song have been done by black artists — Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin — just as the best versions of “Old Man River” have been done by black artists.

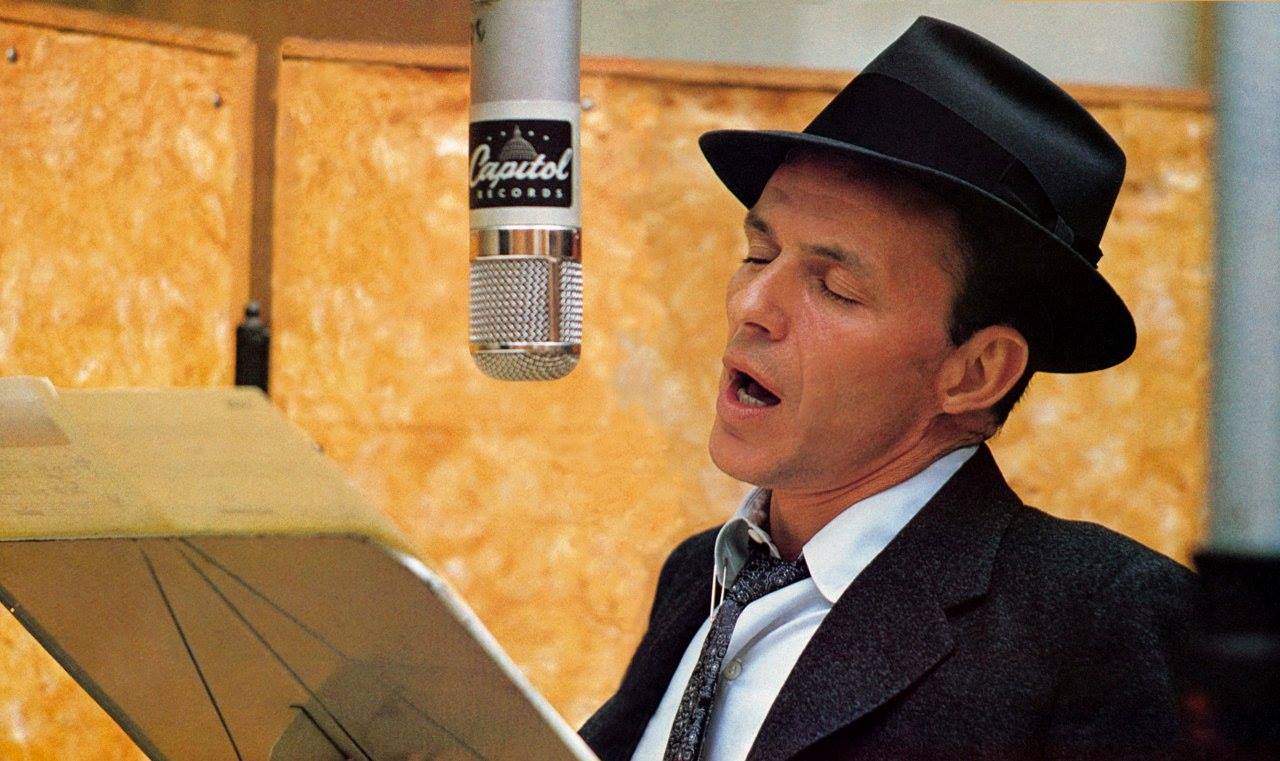

Sinatra’s version above is way too white — it’s like an academic commentary on an African-American song. It doesn’t enter into the black idiom the way the song’s (white) composers entered into it. Bob Dylan, a white singer who has always had a special feel for the blues idiom, has performed the song a number of times over the years.

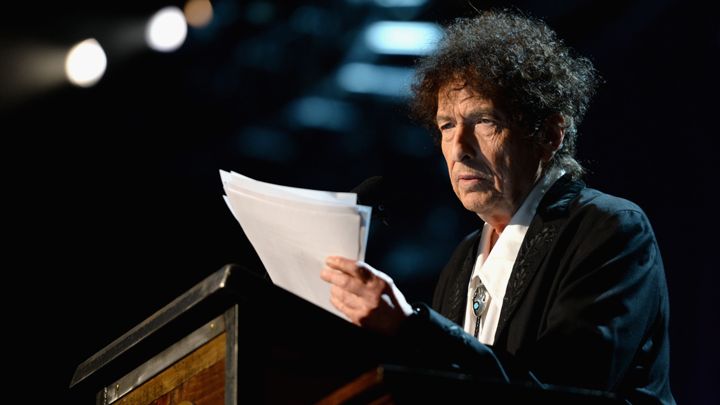

Above Dylan sings it back in 1985, when his voice was stronger and sweeter than it is today. It’s a lovely performance but it’s got nothing on the version that closes Dylan’s new album Shadows In the Night, which is moving beyond my ability to convey, except to say that I’ve listened to it twice and it’s made me cry twice.

Black blues singers regularly performed, but rarely recorded, Tin Pan Alley songs written by white composers. (Ray Charles, whose musical taste acknowledged no boundaries, offered his version of “That Lucky Old Sun” on an album that also included “Old Man River” and “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”.) White artists have often been moved to try and sing the blues — with mixed results. This is all part of the complex conversation of American musical culture.

Dylan’s version of “That Lucky Old Sun” on his new album is one of the most eloquent contributions to that conversation in the whole history of American recorded music.

Thanks to reader Ken for bringing the 1985 performance to my attention!