Late night melancholia on vinyl . . .

Category Archives: Music

AT THE START OF THE JOURNEY

CORN RIGS

I ha’e been blythe wi’ comrades dear;

I ha’e been merry drinkin’;

I ha’e been joyfu’ gatherin’ gear;

I ha’e been happy thinkin’:

But a’ the pleasures e’er I saw,

Tho’ three times doubled fairly,

That happy night was worth them a’,

Amang the rigs o’ barley.

Corn rigs, an’ barley rigs —

Corn rigs are bonnie:

I’ll ne’er forget that happy night,

Amang the rigs wi’ Annie.

Let’s face it — when all is said and done, the great fucks of your life are what will crowd your heart in the hour of your death.

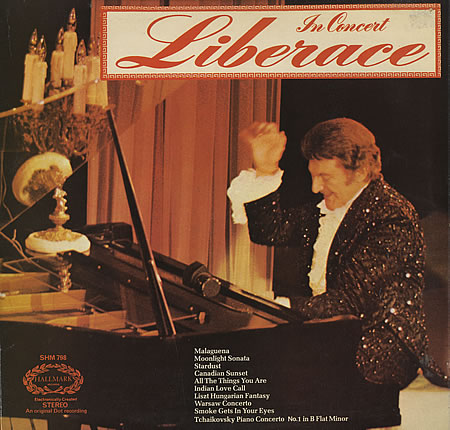

BEHIND THE CANDELABRA

Liberace was one of the most important cultural figures in American history. In a time of vicious and legally enforced homophobia, Liberace stood up in front of America and said, in every way but words, “I’m gay, I love being gay — isn’t being gay wonderful?” And America, in its curious, genial voice of denial said, “Yes — being gay is wonderful!”

This is less odd than it seems. I would venture that almost every family in America in the 1950s had a gay member somewhere in the flock, or a gay friend of the family — the effeminate uncle or cousin who never married because he “never found the right girl”, the two spinster librarians who lived together their whole lives as domestic partners because they “never found the right guy”.

One could deal with such people by denying, as they denied, who they really were, but the situation created tension all the same. What a relief it would have been to be able to say, “Yes, Uncle Ted is queer as a three-dollar bill, but he’s a good old boy, all the same.”

Liberace was everybody’s queer Uncle Ted — he allowed us to love and celebrate Uncle Ted’s queerness by proxy. Indeed, Liberace’s effeminacy made Uncle Ted look almost macho — as macho as a Hollywood leading man.

Steven Soderbergh’s biopic Beyond the Candelabra doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of how important and anomalous Liberace was. The real Liberace was way more effeminate in style than Michael Douglas’s impersonation suggests. He was so effeminate that he could seriously unsettle straight men — yet so charming and unapologetic about his persona that the most uptight of straight men could still find a way to love him.

At the same time, the real Liberace had balls, in his furious presentation of a gay persona that might well have gotten him lynched, and certainly run out of show business, if that persona had ever turned sour in the public mind. Douglas’s Liberace doesn’t convey the steely self-confidence, the irrational courage — or perhaps just the sheer reckless madness — of the real Liberace.

By concentrating on his later years, Soderbergh can’t really convey just how big Liberace was, once upon a time. Until the advent of Elvis Presley, Liberace was the most successful performer in America when it came to filling large arenas. He was an entertainment phenomenon, a genuine superstar.

Soderbergh reduces Liberace’s story to a melodrama about an aging queen who finds and loses something like true love, amidst a life of gaudy consumption that doesn’t nourish the soul. Yawn. Douglas and Matt Damon give fine performances in the film, and its heart is the right place — but it misses what was really interesting about Liberace.

What you will not find in Beyond the Candelabra is the man who had a great intuition and bet his life on it — the intuition that America was tired of denying its homosexual uncles and aunts and cousins, looking for a way to just stop worrying about homos.

The switch in attitudes in this country about same-sex marriage has come with astonishing speed — it’s as though we had just been looking for an opportunity not to worry about it anymore. Liberace, in his way, offered that same sort of relief from worry. “Do I seem like a nice person?” he asked. “Do I have a little talent as a piano player? Do my vulgar outfits make you gasp and laugh? Then relax — don’t worry about who I’m going to be fucking tonight. It’s not important and it’s none of of your business anyway.”

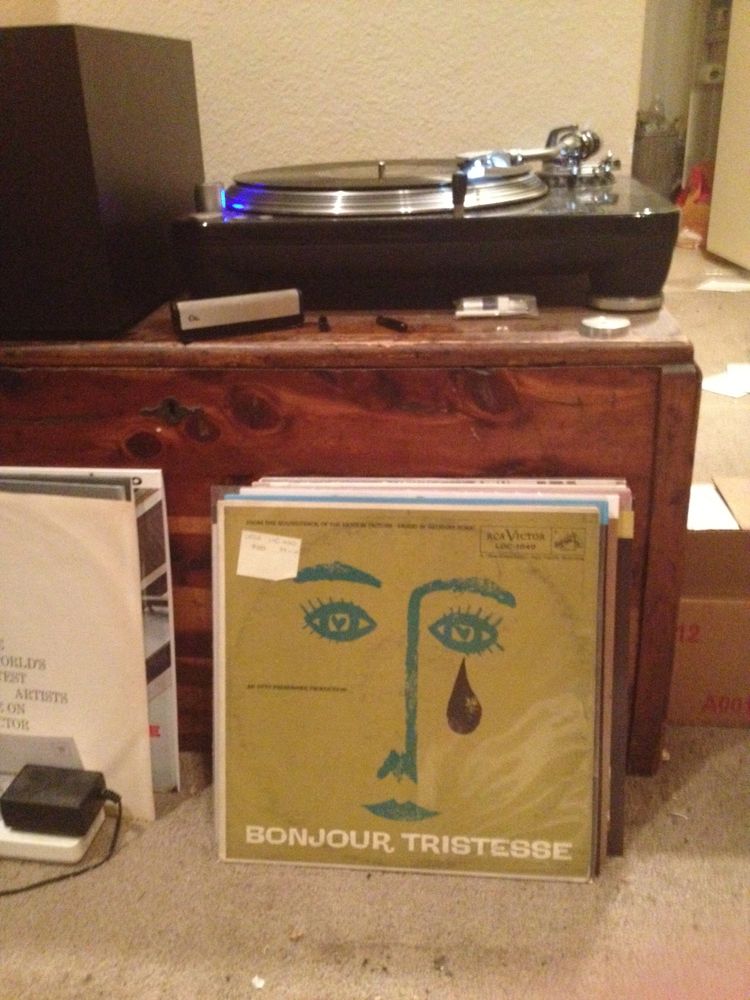

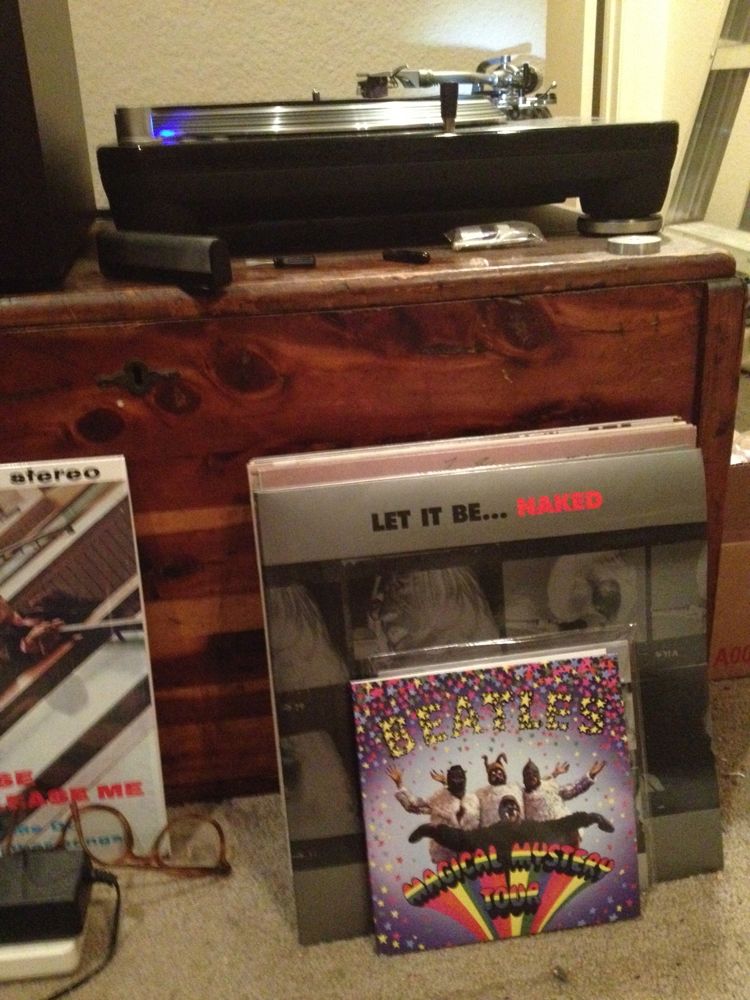

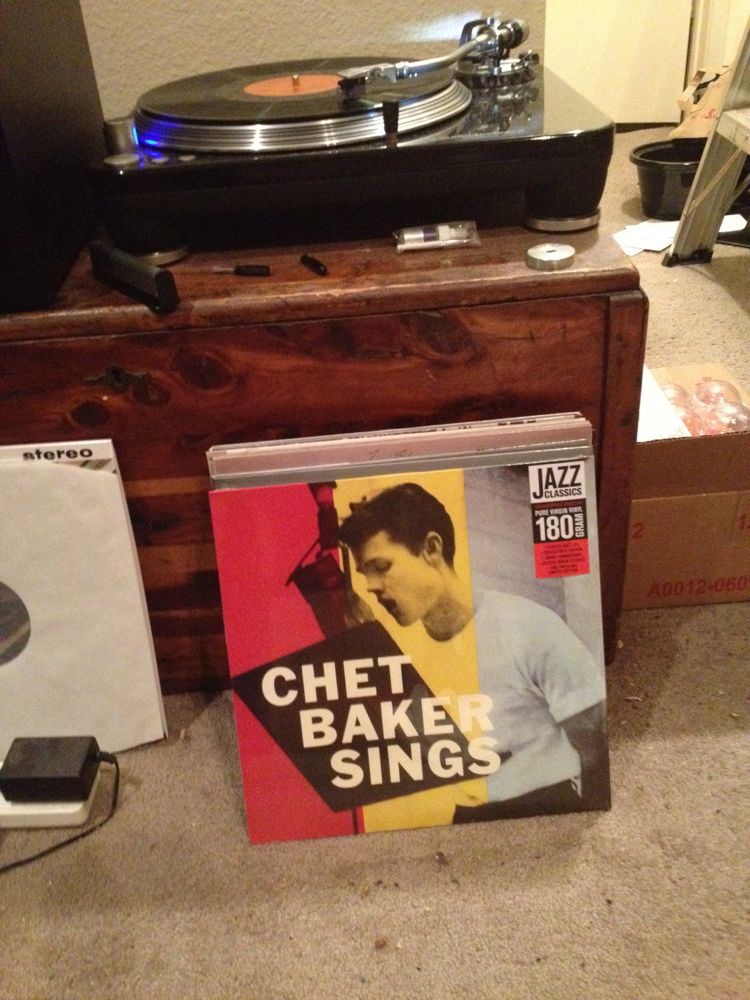

WHAT I’M SPINNING NOW

WHAT I’M SPINNING NOW

If there ever was an album that cried out to be spun on vinyl, it’s this one. Just set it turning, drop the needle and suddenly you’re on a shabby couch in a college dorm room in 1953, making out with a co-ed in glasses who has no idea how cute she is or what’s she’s going to be whispering in your ear by the time the album spins to a close.

Am I getting carried away? Sure — that’s what this LP, in its devious and sinuous way, is all about.

SPANISH IS THE LOVING TONGUE

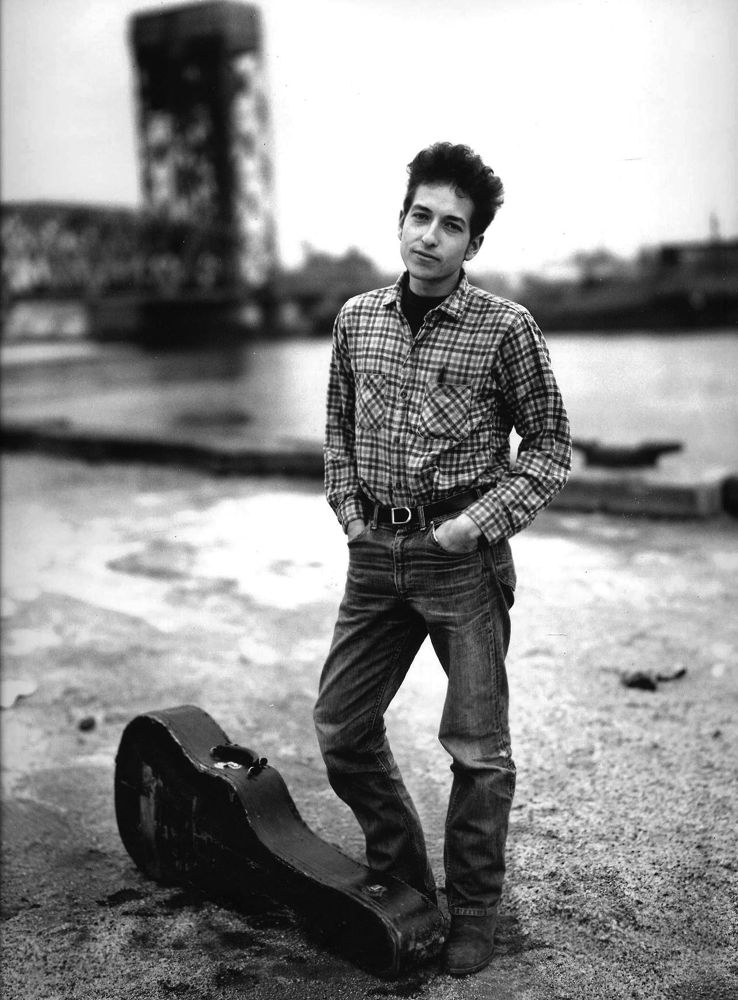

One of my favorite Dylan performances — that’s him on piano, too . . .

I wrote a short story inspired by this song:

Available in this collection — Fourteen Western Stories.

IN THE DAYS OF ’49

I’m not getting nostalgic or anything, but the days of ’49 — damn . . . those days . . .

Oh, my goodness.

GIRL WITH BEATLES RECORDS

Via Human Faced Dog . . .

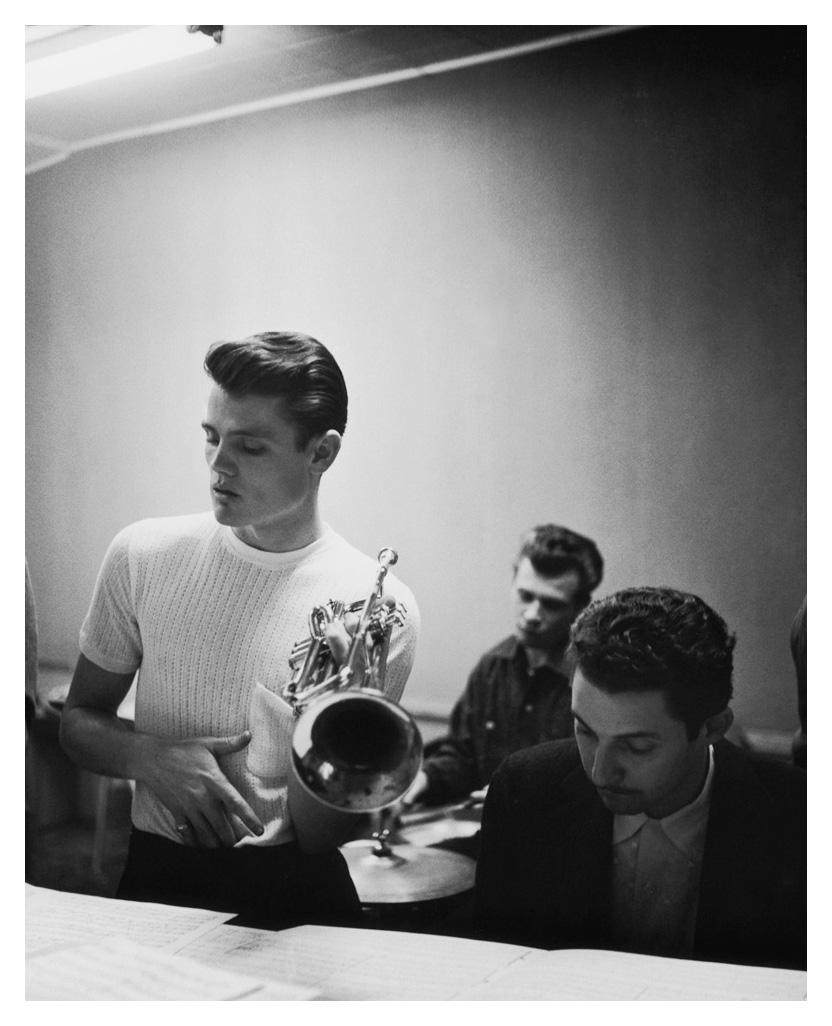

CHET

WE ARE THE WORLD

If you don’t think Dylan is a great singer, listen to what he does with this ditty . . .

WHEN I FALL IN LOVE

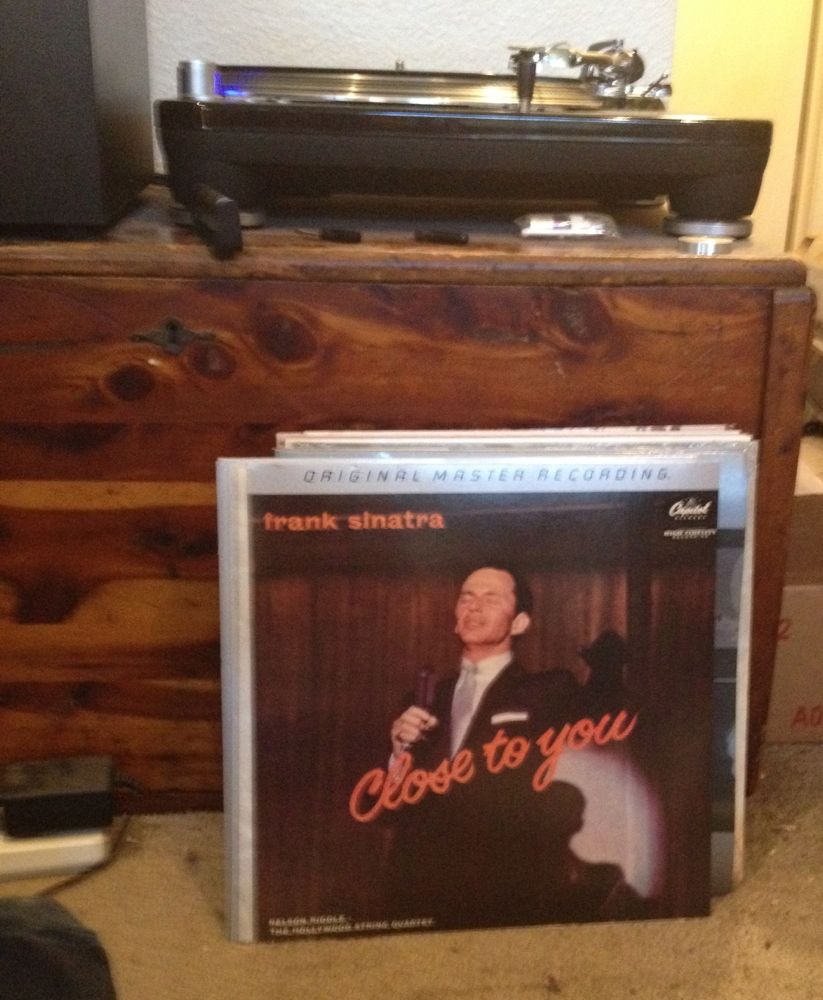

WHAT I’M SPINNING NOW

AMERICAN MUSIC 1954

1954 was an interesting year for American popular music. Charlie Parker was coming to the end of his earthly run, but his frequent collaborator Miles Davis was kicking his own drug habit and finding the distinctive voice that would open up years of amazing creation. Thelonious Monk switched labels, from Prestige to Riverside, a move that opened his way to the best work of his career. Frank Sinatra meanwhile had moved from Columbia to Capitol and made the first of the albums for that label which together constitute one of the greatest legacies of American popular art.

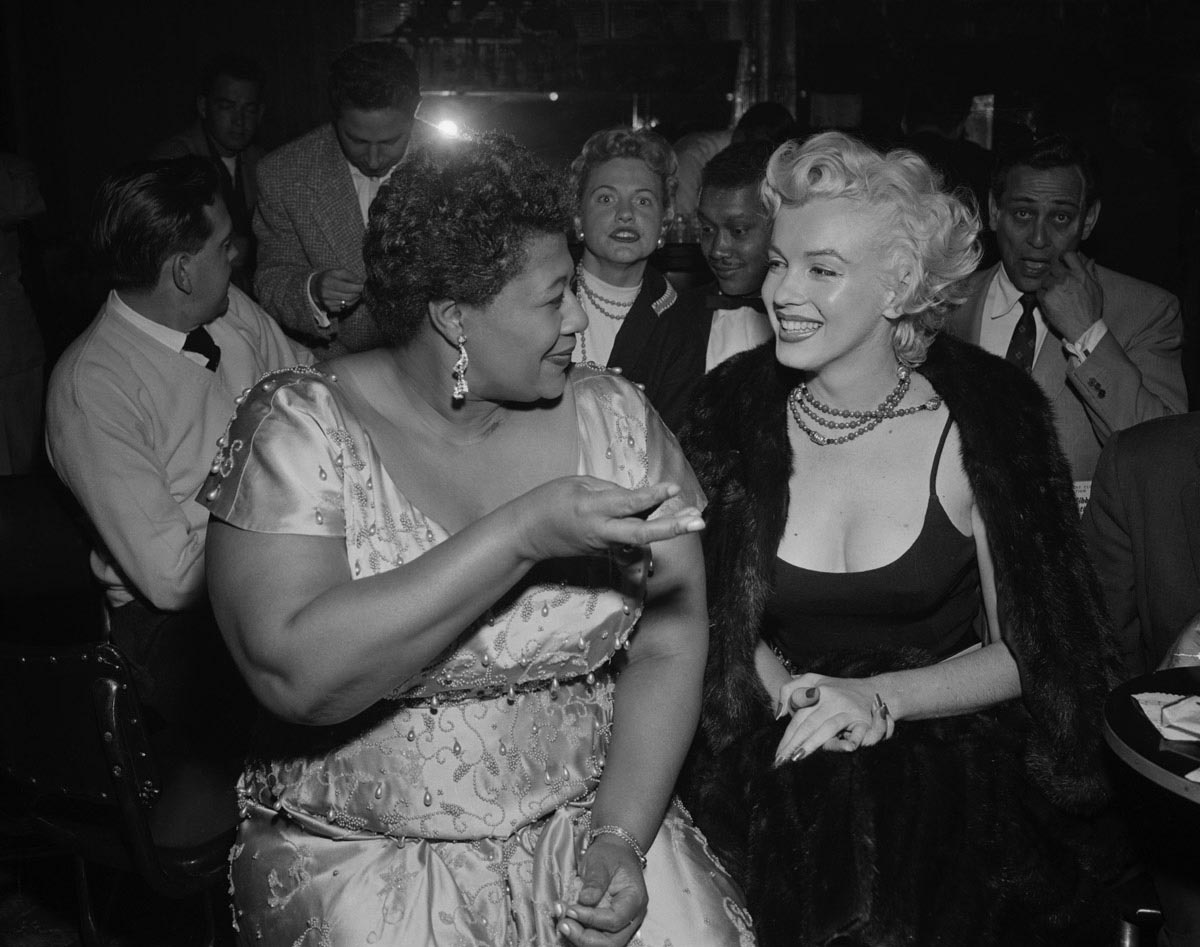

Ella Fitzgerald was in the midst of a change as well, moving away from her showy scat and novelty numbers to quieter, and utterly brilliant interpretations of the great American songbook. Jazz artists like Jimmy Giuffre and Chet Baker were developing a distinctive West Coast sound, cool and laid back, even as the pioneers of bop grew thornier, challenging convention in bolder and bolder ways. Anita O’Day, feeling her oats as a solo performer, was adding her own flavor to the cool West Coast sound.

The Big Band era was all but over. The logistics of taking a large ensemble on tour no longer made economic sense. Swing ensembles got smaller, even as they faced competition from the hard-driving R & B groups that appealed to younger listeners. In 1954 Elvis Presley recorded the proto-rock “That’s All Right, Mama” for Sun Records, a regional hit for the label, and Bill Haley recorded “Rock Around the Clock”, which became a national break-out hit when it was featured in a popular movie. The rock and roll locomotive was getting up steam.

In Los Angeles, the black music scene on Central Avenue was moving to venues on Western Avenue, closer to the center of the entertainment world in Hollywood, and became further de-Centralized as more and more upscale clubs started booking black artists. In November of 1954, due to the personal intervention of Marilyn Monroe, Ella Fitzgerald became the first black artist to play the Mocambo, The Strip’s swankiest joint.

The national charts were dominated by smooth-voiced crooners and vocal groups, whose dreamy blandness diverted attention from the drastic changes for American popular music gathering momentum just over the horizon.

Revolution was in the air. Sinatra’s move from conventional crooner to subtle vocal dramatist, Fitzgerald’s move from pyrotechnical scatting to elegant interpretation, were just as startling in their way as the emergence of rock and roll. Much of the revolution in progress played out in the clubs and recording studios of Los Angeles, where the tensions of the time made the musical scene alive with electric energy, vibrant with possibility.