One of the last of the great old-fashioned Broadway musicals — tuneful and witty songs and some delightful vocal performances by Streisand.

Click on the image to enlarge.

The lyrics Oscar Hammerstein II wrote for Richard Rodgers’s melodies were always clever and professional, though they sometimes verged on the treacly. Still, what an avalanche of beautiful music in their collaborations — we’ll never encounter anything like it again. When the lyrics rise to the level of the music, as they often do, you get examples of musical theater at its very best.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Poster for the 1902 stage musical, which had at least as much influence on the 1939 movie as the books they were based on.

Many of the musicals Arthur Freed helped create at MGM were derived from the theatrical world of his youth, which he delighted in magically summoning back to life. He would have been eight in 1902. He would have been ten in 1904, the year in which Meet Me In St. Louis is set.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Another bit of sublimely surreal cinema from Elvis — the film is Girls! Girls! Girls! With thanks to Tony D’Ambra.

Click on the image or here to see something amazing.

This lip-dub musical number was staged as a surprise wedding proposal. As a gesture it’s heartbreakingly beautiful, but its also an exhilarating piece of cinema — it works because it’s all done in one shot, the performance tension just builds and builds, instead of getting dissipated in hysterical Baz Luhrmann or music video cutting. Hollywood once understood the power of elaborately choreographed musical numbers done in long takes — Busby Berkeley and the Freed Unit at MGM specialized in them — and people are still drawn to them, only now they have to make them themselves, because Hollywood is currently run by idiots.

This video will go viral because it’s so joyful and astonishing — the Hollywood mediocrity machine will take no notice.

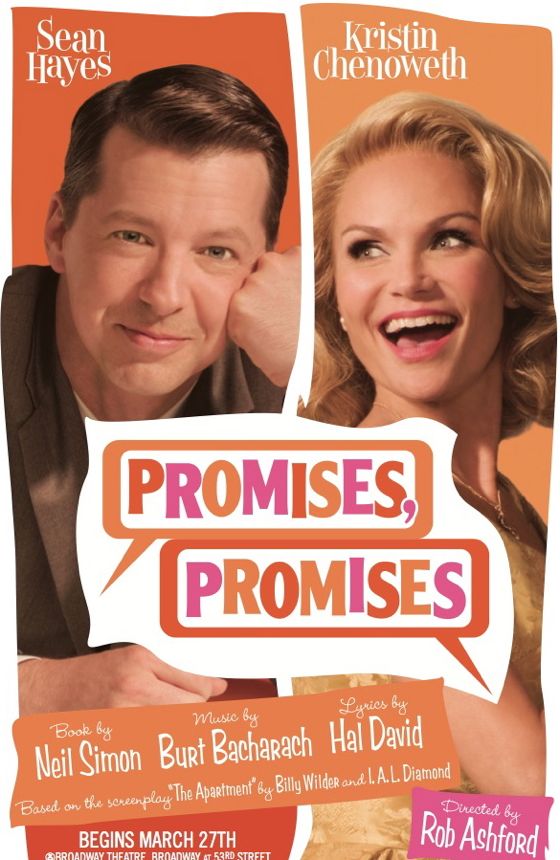

My friends Mary and Paul Zahl made a lightning raid on New York City recently (from Florida!) to see the Broadway revival of Promises, Promises. Here is Paul's report on the show:

LITTLE NOT BIG, THEREFORE BIG

I think critics make a mistake when they bring ideology to a production

of the theater. In the case of the new revival of the 1968 musical Promises, Promises

by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, with book by Neil Simon, a lot of

ideology has flowed out on paper. A lot of energy has flown, for

example to the performance of Sean Hayes, the lead actor, and whether

a gay actor can portray a non-gay hero.

Energy has also flown to the attitudes, within the story, concerning

relationships in the work place between men and women, attitudes that

are supposedly typical of the 1950s and early 1960s and no longer of

today. (The musical was written and first performed in 1968, although

it is closely based on Billy Wilder's 1960 film The Apartment, which he co-wrote with I. A. L. Diamond.)

As I say, a lot of present-day ideology has become involved in the

critical reception of this Broadway revival of Promises, Promises. No

matter that, however, Variety reports that Promises, Promises is a

commercial success. The weeknight performance my wife Mary and I

recently attended was sold out, not one empty seat; and the audience

was overwhelmingly appreciative, interrupting the show frequently and

offering the cast a long standing ovation at the end.

For myself, Promises, Promises is a little story, about a “little guy”

who wins the girl — because he really loves her and doesn't use her —

and therefore a big story. In drama, so goes my notion, when a

personal story is well and compassionately told, that story becomes a

big story. On the other hand, attempting to weight a personal story

with ideology, especially pre-conceived ideology, diminishes the

attempt.

Promises, Promises narrates the disillusionment of a “little guy” at

Consolidated Life, whose crush on a “little” fellow employee turns out

to be a crush on the mistress of his married boss. C. C. Baxter's sweet

and selfless crush on his “angel in the centerfold” ( reluctant

mistress to the unscrupulous Mr. Sheldrake) is crushed in the first

act, and on Christmas Eve! However, when Miss Kubelik tries to commit

suicide out of her own disillusionment with Sheldrake — after a sorry

tryst in C. C.'s apartment — things both fall apart and come together.

Baxter shows real love for his true love, who seems hopelessly and all

the time in love with another man. With the merciful intervention of a

kind and honest doctor who lives next door, together with C. C.'s urgent

rising to the occasion of her overdose, Miss Kubelik rises from the

dead, or the near dead.

This love from a real and kind man, C. C.

Baxter, as compared with the cynicism and selfishness of boss

Sheldrake, touches her, and finally wins her heart. The curtain “clinch” is credible, unsentimental, and very, very touching. It is

made even more credible by the reprise, this time with a positive

vibe, of Bacharach and David's famous song “I'll Never Fall in Love

Again”.

Why does the audience cry at the end? Why was the applause sustained

and very loud? Why did the people leave moved, and happy? I think

it's because the love of C. C. Baxter and Fran Kubelik is a universal

story enacted within a particular case. C. C. wins Fran. He saves her

life, both physically and emotionally; and at the very moment when her

long, passionate, hopeless affair with Sheldrake is exposed — at the

very moment! This is a little story about little people. It is

therefore big. Why? Because it's about everybody. Everybody knows

about the little guy. Almost everybody, male and female, is now or has

at some point been the little guy. It comes with being born.

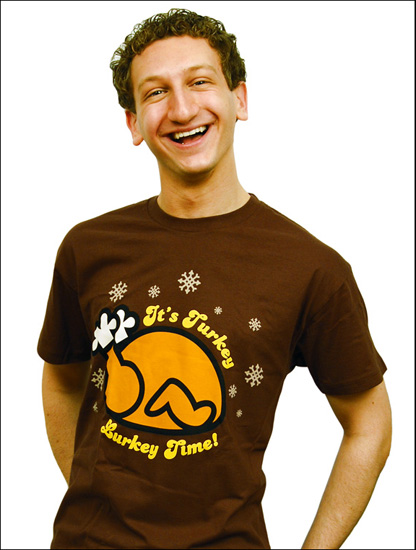

There are a lot of theatrical touches to Promises, Promises that are

worthy of comment. The notorious Christmas Party song entitled “Turkey

Lurkey Time” is a number people seem either to hate or love. Mary and

I happen to love it. I think we could say we LOVE it. “Turkey

Lurkey Time” is just so unusual. Is it about men being turkeys? Mary

thinks so. Is it about the Christmas turkey, soon to lose his head?

Well, yes. Is it a song about the sheer euphoria of Christmas revelry

and drunkenness? Yes, too. Is it a smashing production number with

great ensemble dancing and an unpredictable finish? Yes, that, too.

Anyway, “Turkey Lurkey Time” has to be seen and heard to be believed;

and I, for one, am still singing it. (I made a mistake in the lobby at

the end, as we were leaving the theater. I was too cheap to buy the T-shirt of “Turkey Lurkey Time”, with snowflakes against a brown

background. Heaven: and I missed it.)

Then there is the unexpected moment of compassion for the “villain”,

J. D. Sheldrake. He sings a song entitled “Wanting Things”, about his

compulsion for wanting things he cannot have. The subject of the song

is what theology calls “concupiscence”. As he tolls his confession,

shadows of the several women in his life, all in scarlet but

half-hidden by the lighting, approach him, then slowly walk away, and

vanish. The number is haunting, and also even-handed. No person is

completely a villain.

The producers of Promises, Promises have added two songs from the

Bacharach-David repertoire to their revival of the show. One of them,

“A House Is Not a Home”, has to be one of the great American pop

songs. Both lead characters, Fran and Chuck (C. C.), sing it in

separate contexts, at different points in the narrative. It is almost

unbearably affecting. The actress Katie Finneran (above) also has a star turn

as Marge MacDougall, the woman Chuck picks up in a bar on Christmas

Eve just after he has learned the truth about Fran's affair with

Sheldrake. Critics of the show who panned it otherwise, mostly for

ideological reasons of one kind or another — you can adore Mad Men

but you can't say a good word about Promises, Promises — loved Katie

Finneran's extraordinary scene. You have to agree with the critics

about the scene, and the actress. But it's also true that Sean Hayes,

the lead, reveals a comic brilliance and timing as C. C. Baxter; and

Kristin Chenoweth has a lovely voice and compelling stage presence.

(To me the actress seems a little petite for the role, given the

slightly tough persona she is supposed to have.)

Two other things to mention:

The character of Dr. Dreyfuss is played by Dick Latessa (above, with Chenoweth and Hayes), who puts this

role on the map. Dr. Dreyfuss is the physician/wise man/priest of the

play and even invokes God, sincerely, in a moment of crisis. Also, the

number, “Where Can You Take a Girl?”, which is reprised twice by an

enthusiastic quartet of young executives, is comic and even slapstick.

We would wish to believe that the kind of thinking expressed in the

song doesn't take place any more. But it does, whatever one's moral

judgments are. It's just that today the targets are not “secretaries” but “part-time staffers”, or “interns”, or “campaign workers”, of both

sexes. “Where Can You Take a Girl?” is a spoof. Everyone in the

audience laughed, even if they didn't quite want to.

Visually, the play is saturated in early '60s office decor. (Think

kidney-shaped ash trays.) The art direction reminded me of Frank

Tashlin's 1957 Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?. But the props don't overwhelm the story and the music. The

choreography is terrific. The dancers and their costumes look right to

the period, and they're not small bodies. Yet there are also not too

many of them. The high points of the dancing occur at the very

beginning of the play and during “Turkey Lurkey Time”. (As far as I am

concerned, you could almost rename the show “Turkey Lurkey Time”, that

song is so eccentric and memorable.)

Mary and I had a blast. It's rare you do something on an impulse —

like getting on a plane within a few hours of deciding to go, with the

sole purpose of seeing one show you hope you're going to like — and it

works. Promises, Promises works. It works on almost every level. If

you are going to take offense — at anything — on purely ideological

grounds, I guess you could infer something you didn't like. That may

be true of almost any piece of popular art. But I think it would be

doing an injustice, here, to the combined talents of Billy Wilder and

I.A.L. Diamond, of Burt Bacharach and Hal David, of Sean Hayes and

Kristin Chenoweth, Dick Latessa and Katie Finneran; and of Neil Simon.

Together they bring together a story of a little yearning man and a

little beat-down woman (Kerouac's understanding of a “beat-ness”),

whose love affair becomes a big story.