Thomas Riis's fascinating book Just Before Jazz examines the influence of black composers and performers on American musical theater between 1890 and 1915 — that is, just before the era in which the modern book musical began to take shape.

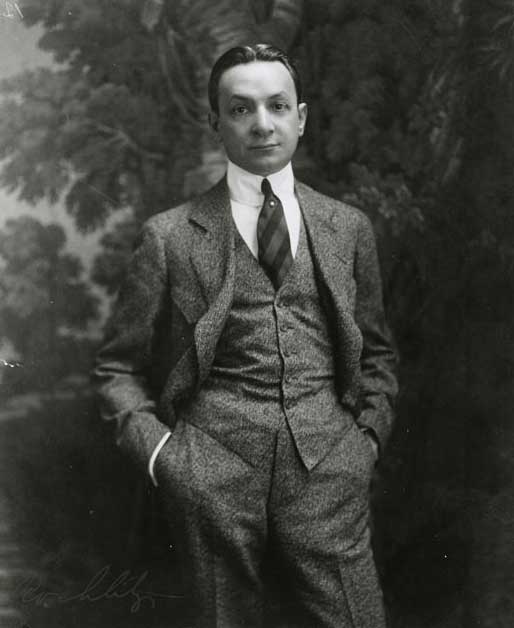

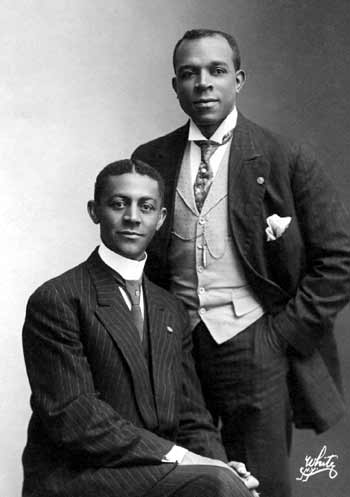

The songs of black composers were very similar in many ways to the popular songs written by white composers, even the white composers of operettas. A number of black composers in this period (like Will Marion Cook, below) were highly sophisticated, classically trained musicians, capable of writing and performing in any style. (Many of them were “slumming” in popular theater because of barriers to their involvement in more refined areas of practice.)

What distinguished their work was the incorporation of the sort of syncopations found in ragtime, which became a popular sensation around the turn of the century. Their work didn't emphasize such syncopations to the degree that ragtime did — they were more like stylistic inflections — but they thrilled audiences of the time.

Among the most popular songs in this period, an astonishing percentage were written by black composers, and they included not only minstrel-type songs but ethnically neutral ones. It was the purely rhythmic lilt that made the difference.

Almost all of these songs were first done for musical shows originating in New York City, often in Broadway productions, leading Riis to argue that black composers bear the primary credit for introducing black musical strains into the American musical. Berlin and Kern and Gershwin weren't “reaching down” into an exotic black musical culture for inspiration — they were responding, artistically and commercially, to developments in the world of musical theater all around them.

You have to wonder why these black composers aren't better known today. Partly it's because the lyrics of many of their songs are offensive to modern ears — the “coon song” was a typical genre, with its caricatures derived from minstrel shows. As black songwriters became more powerful, however, they toned down the uglier aspects of these caricatures, leaving stereotypes comparable to those attached to other ethnic groups like the Irish and the “Dutch” (as Germans were once called.) These stereotypes aren't congenial to our present tastes, perhaps, but they aren't exactly vicious, either.

More importantly, these black composers failed to achieve wider celebrity, and failed to enter our cultural memory, because they could not participate fully in the flowering of musical comedy in the later decades of the 20th Century. Their songs were bought and performed by white performers in vaudeville, were sometimes interpolated into shows with white casts and were disseminated nationally via sheet music, but in the theater, they wrote primarily for all-black shows. Broadway had a place for such shows, but it was a limited place.

Black composers were very rarely hired to provide complete musical programs for shows with white casts — they never became part of the mainstream of producers, musicians and writers who created the ordinary run of Broadway musicals. White composers adapted the style of their black peers within an establishment that stayed predominantly white.

So today, when we hear Judy Garland and Margaret O'Brien singing “Under the Bamboo Tree” in the movie musical Meet Me In St. Louis, we likely have no idea that this song, a monster hit in 1903, with a tune that is still familiar and still infectious, melodically and rhythmically, was written by three black men, James Weldon Johnson, his brother Rosamond Johnson and Bob Cole. Below, a portrait of Cole and Rosamond Johnson:

But the past, of course, as an old Russian saying has it, is always unpredictable.