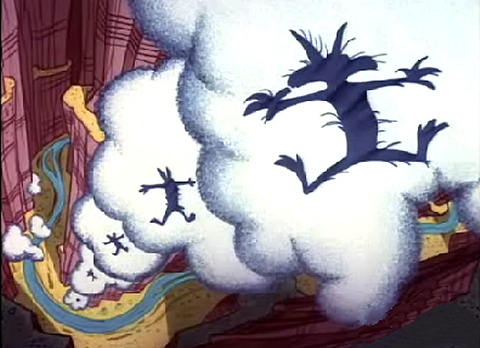

“Something’s wriggling out of the shadow . . . It’s as large as a bear and glistens like wet leather. But that face, it . . . it’s indescribable . . . The eyes are black and gleam like a serpent. The mouth is V-shaped with saliva dripping from its rimless lips that seem to quiver and pulsate . . .” It’s a war of the worlds! It was 1938, a Sunday, on the eve of Halloween just as the sun made its way below the horizon, and the moon began to warily take its place. Little did the people of the seemingly secure Grover’s Mill know that this could very well be the last night sky they would ever see. The last sky the entire planet might see . . . Millions of Americans sat glued to their radios as a familiar evening broadcast of dance music was suddenly interrupted by an urgent new bulletin. Invaders from Mars were attacking! This spine-chilling broadcast bent believers to its will in such a way that it is still considered the single most important event in radio history today.

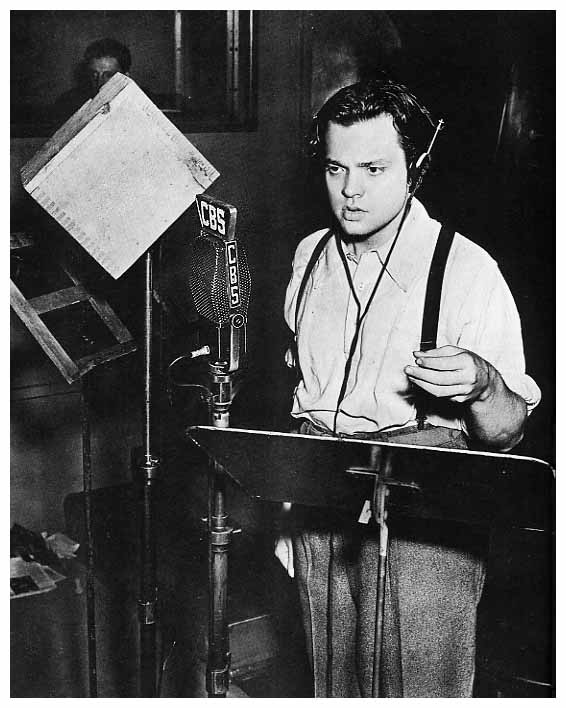

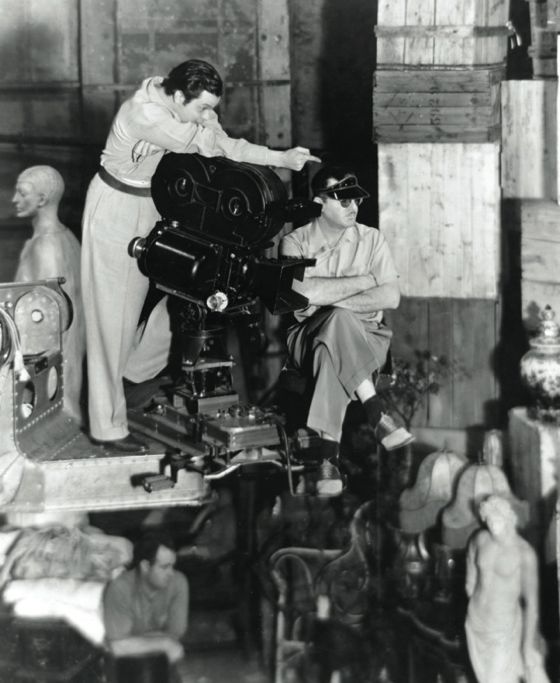

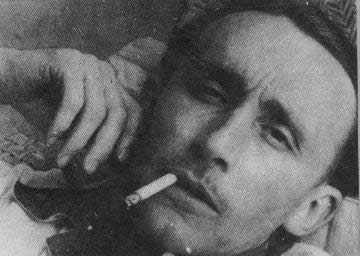

The “War of the Worlds” radio-play was the brainchild of Orson Welles, a talented, 23-year-old actor, producer, and theater director. In order to fill empty air space, CBS offered Welles and his dramatic group, the Mercury Players, a program every Sunday night called Mercury Theater on the Air. The program was broadcast out of New York City, and included dramatic adaptations of plays and books. On the night in question, Orson Welles was presenting an adaptation of the famous book The War of the Worlds by H. G. Welles (written 1898). Orson, his partner John Houseman, the writer Howard Koch, and the small cast of Mercury Players, decided to present the War of the Worlds as if it were the actual event happening in real time. The audience was lulled by the “soothing” sounds of the dance band music, when suddenly one of the actors in a carefully planned interruption pretended to be an actual CBS network announcer with frightening breaking news, from New Jersey. America was under attack from Martians in giant war machines. For the next hour, the story escalated, with more detailed information as the event unfolded. According to the “newsmen,” cities were being destroyed, state militias were demolished, dark, poisonous alien gas was purposefully unleashed across the country, citizens were getting eaten by the invaders, and others were being crushed by huge, metal Martian machines. Clearly the end of the world was at hand. The precision, detail, and very powerful acting made the broadcast realistic, and created doubt even in the minds of people who thought they could just shrug it off as “nonsense.”

It is estimated that there were about nine million Americans across the country listening to the broadcast that night. Many were entertained and amused. Many did not know what to think or how to react. There’s no way to know how many people were actually frightened. But we do know that about 1,750,000 people were scared enough to take some action. (Bogdanovich, Welles, 346) Despite the fact that there were multiple reminders that it was just a fictional presentation, imaginations ran wild.

Panic was rampant. Emergency switchboards were on overload. People blocked off their doors and hid in their attics and basements. Shops closed, theaters closed, churches were filled, guns were cocked, and people were screaming in the streets, “The world is ending! The world is ending!” Many fled. Others organized small, armed resistances. Some people thought bigger. Governor Earle of Pennsylvania volunteered his state’s militia to help New Jersey fend off the Martians. A group of twenty families ran out of their apartment building with wet towels on their faces to “repel Martian rays.” Hospitals were flooded with offers from nurses and doctors to help out with all the “war casualties.” A modern day Paul Revere, blowing a loud horn and screaming warnings of the Martian invaders, motored through the streets of Baltimore. One man “bound for open country” had driven away for about ten miles, until he realized that his poor dog was still tied up in his backyard, so he sped all the way back to rescue him, “risking” his life against the aliens. It was recorded that one man almost drank a bottle of poison, telling his wife, “I’d rather die this way than that!” (Although were no actual deaths or suicides on record.) Rhode Island’s electric company was prompted into considering turning off all the lights in the entire city “to make it a less visible target.” (Oxford, 184 and 185)

Why did so many people believe that the broadcast was real? One of the reasons was the artistry of the broadcast itself. Orson cleverly planned every detail. He used real names of actual places and simulated both the “live” band music and the “broadcasters” with perfect skill. He knew what competing radio shows were on that night and when people would be likely to switch over to CBS. The actors did a superb job, including imitating the voice of President Roosevelt. Orson also knew how to build the intensity of the story for maximum dramatic effect. Another reason that the broadcast was so believable was that many listeners came in part way during the story and did not hear any of the four announcements reminding people that it was just a radio-play. Even more people heard about the alien invasion second-hand. Rumors spread like wild fire. Rumors and wild imaginations led to many false, eyewitness reports. Panic caused people to see and hear things that were not actually occurring, which only increased the panic in a vicious cycle. For example, one man in Grover’s Mill shot up a deathly, alien war machine with his shot gun, only to discover later that is was just his neighbor’s rather humdrum water tower. Some New Yorkers believed they heard Martian flying machines, or weapons firing, or saw the city on fire. Another man flipped his car over twice as he drove 80 miles an hour trying to escape Martian death rays. (Oxford, 184, 185) False eyewitness reports were widespread and fed the story even more convincingly than the broadcast itself. Another contributing factor was the newness of radio. In 1938, people were naïve about joke broadcasts. These were days before, Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Updates,” or Monty Python’s Flying Circus, or Steve Colbert. If the news (especially CBS) said something was true, people tended to believe it.

It’s one thing to try to understand why people believed it, but it’s another thing entirely to try to comprehend why people were so afraid. To grasp this, it is necessary to look at the historical context of the event. The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed it had a profound emotional and psychological effect on the American people. (Rosenburg, 1) Their sense of security in their society had been badly shaken. In 1938, most Americans were still struggling to get back on their feet. Optimism for the future was at all time low. Equally important were the events unfolding in Europe and Asia. Spain was in the middle of a civil war between socialists, fascists, and royalists. Japan began a series of invasions into China, killing thousands of innocent people. (Miller, 1and 2) Hitler was on the rise, making inflammatory speeches and building up a massive military. His attacks on Jews were escalating. In 1938, he invaded and took over Austria, and began his invasion of Czechoslovakia. (World History, 1938-1939, 3) Many Americans watched newsreels or listened to radio broadcast of Hitler’s speeches. In response, America was building up its army and its navy. Many Americans began to think that we would be drawn into another World War, so soon after the first one. This created an atmosphere of tension, and underlying fear. (Rosenburg, 1, 2) In fact, when Orson’s broadcast reported that “shells were falling” towards Earth, many believed that it was the beginning of Hitler’s assault of America. (Lovgen, 1) Houseman himself recognized later the importance of the historical context, when he said, “Only after the fact, did we perceive how ready and resonant the world was for the tale.” (Oxford 189)

Newspapers saw themselves as the voice of calm reason in troubled times. This made them particularly hostile about the broadcast. As it turns out, many of the newspaper reports were inaccurate and exaggerated. Newspapers reported suicides, heart attacks, and widespread destruction of property, and held the Mercury Theater responsible. Some accused the newspapers of being spiteful and jealous because newspapers had been losing more and more popularity and advertising money to radios. Newspapers used Orson’s broadcast as a way of pointing out the dangers of impulsive broadcasts. As a form of mass media, radios were capable of trickery and deception.

Before the “War of the Worlds” broadcast had even ended, cops were already storming CBS Studios. Fortunately, they didn’t know who to arrest — or even what the crime was — but they were ready. By the next morning, the stories were all over the newspapers. When people learned that it had all been a hoax, most responded with good humor. Many did not. The mayor of Flint, Michigan threatened to personally find Orson Welles and punch him in the nose. Some legislators, led by Iowa’s Senator Herring, called for new laws to prevent anything like this from happening again. The federal communications commission, the government agency which supervised radio, called Orson Welles a “terrorist” and tried unsuccessfully to decide on a new balance between censorship and free speech. Many denied ever having been duped in the first place. The newspaper, however, kept their pressure on Orson Welles, and soon he was facing $12 million in lawsuits (Bogdanovich, Welles, 19). In time, people came to the conclusion that the broadcast technically wasn’t even a legal offense, so the lawsuits were dropped.

Instead of punishment, the Mercury Theater’s popularity shot up. Campbell’s Soup became their first sponsor. And as for Welles, he instantly became an international celebrity. Throughout the start of the innumerable interviews Welles faced, he claimed over and over that all along that he and his crew had “no idea” that people would take the broadcast so seriously.

Hollywood offered him contracts and he went on to direct major motion pictures, including Citizen Kane, and The Magnificent Ambersons. In later years, Welles revealed that he did, in fact, know exactly the response his “War of the Worlds” broadcast would create, just not quite the magnitude (Bogdanovich, Welles, 18). He admitted that he apparently had said to Mercury Theater players, “Let’s do something impossible, make them believe it, then show them it’s only radio.” (Taylor, 38)

In 1938, it was easy for Americans to see how Hitler manipulated the media to create

fear, panic, and blinding hatred. But no one believed that it would ever happen here. Orson Welles showed the country how susceptible we all are to the powers of the media. It has been over seventy years since the “War of the Worlds” broadcast, but the issues it raised are just as relevant today. With the birth of television and Internet, news can spread quicker than ever before. Not all the news that gets spread is accurate, of course, but it can still influence the way people think and how they act. Networks, broadcasters, and websites need to be thoughtful and responsible. Different networks are run by different political sides, which makes their credibility suspect. (For example: Fox News VS. MSNBC) Therefore, it is crucial that every individual be smart about how he or she interprets, believes, and handles mass media “news.” As Orson Welles decorously described, “War of the Worlds’” was, “The Mercury Theater’s own radio version of dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying ‘boo!’” We must always to remember to look for the sheet.

Bibliography

Edward, Oxford. “Night of the Martians.” American Experiences: Reading in American History. Volume 2. New York: Pearson Education Inc., 2005. 179-190. Print.

Gale. “Welles Broadcasts the War of the Worlds, October 30, 1938.” DISCovering World History. Online Detroit, 2003. Web. 22 Jan. 2011.

<http://find.galegroup.com>.

Lovgen, Stephan. “”War of the Worlds”: Behind the 1938 Radio Show Panic.” National Geographic. N.p., 17 June 2005. Web. 24 Jan. 2011. <http://new.nationalgeographic.com>.

Miller, David. “World History Timelines, 1938.” Din-Timelines.com. N.p., 2002. Web. 24 Jan. 2011. <http://dintimelines.com/1938_timeline.shtml >.

Rosenburg, Jennifer. “”The Great Depression.” About.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Jan. 2011. <http://history1900s.about.com>.

Taylor, John. Orson Welles. Boston: Little, Brown And Company, 1986. Print.

Welles, Orson., Peter Bogdonavich., and Rosenbaum, Ed. This Is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992. Print.

“World History, 1938-1939.” MultiEducator, Inc., 2000. Web. 20 Jan. 2011.

<http://www.historycentral.com>.