The tide is high but I'm holding on . . .

The tide is high but I'm holding on . . .

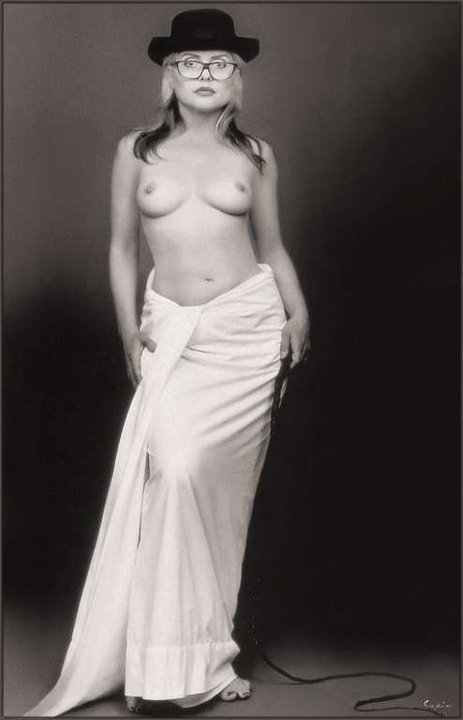

This is Eli Johnson, as she then was, whose latest birthday I wrote about here, on Halloween some years ago, when she was just 17 (and you know what I mean), photographed by Lang Clay.

The portrait is like a John Singer Sargent gone slightly awry.

That's Bill Eggleston above, wearing the bow tie, flanked in the foreground by my friend Lily Chubb on the left and his daughter Andra on the right, at the reception for the opening of his show Democratic Camera at LACMA last week.

The exhibition originated at the Whitney Museum in New York a couple of years ago but has been expanded and beautifully hung at LACMA's Resnick Pavlion — it's certainly the best Eggleston show I've ever seen, with images from every phase of his work from 1961 to 2008. It gives a good sense of the scope and depth of his portrait of America, one of the most important artistic projects of our time.

I attended the show with my sister Lee, on the left with Lily below:

Bill seemed a little overwhelmed by the attention at the reception, and faded a bit in the crowded, stuffy galleries, but revived when he took up a position on an outside terrace. Lily's dad Cotty pulled me aside and suggested that if I had an extra cigarette, Bill could probably use it. When I offered him one he looked at me skeptically and said, “I didn't know you could smoke here.” I said, “You're the star of the show, Bill — you can do whatever you want to do.” He laughed. “Do anything I want and say anything I want,” he said.

He smoked. Nobody told him not to. An endless stream of admirers approached him to offer their respects. (That's me with Lily below.)

I first saw a large selection of Bill's work in 1971, before it was widely known, and realized immediately how important it was. The world's eventual embrace of it never surprised me, and nearly forty years later, his recognition as a master, in shows like this one and many others, doesn't surprise me. It probably doesn't surprise him, either.

[Image © William Eggleston]

Large as the LACMA show is, it represents only a small fraction of his work. Taken as whole, it will represent an extraordinary legacy to the future. He has a kind of calm about it all, a kind of satisfaction in his service to his art and his country. Personal celebrity doesn't seem to mean much to him — what he cares about is showing people what he has seen. He seemed gratified last week that people were looking at it.

If you live in the Los Angeles area, you should really go look at it for yourself.

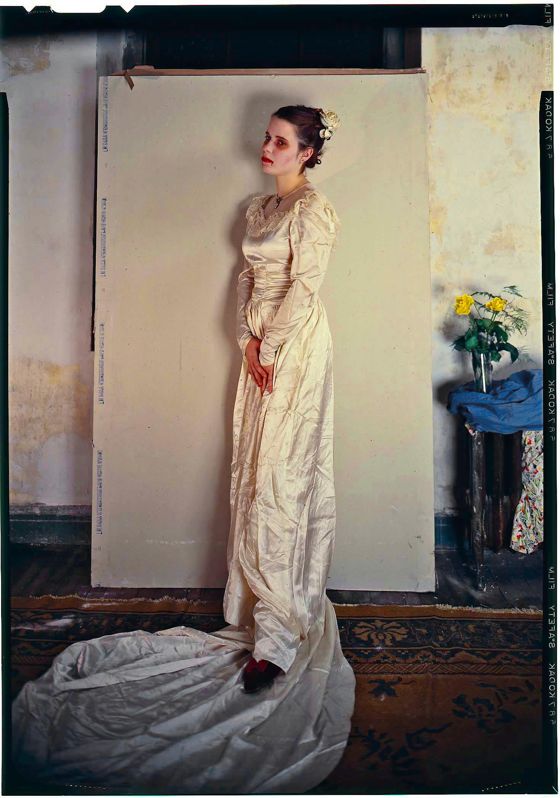

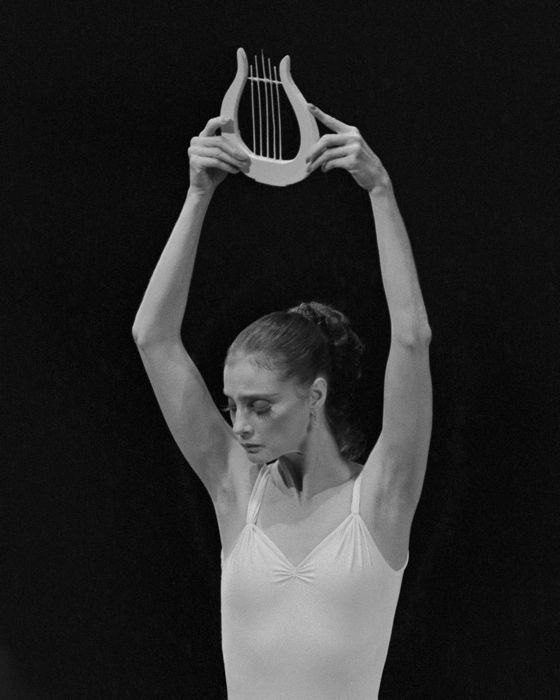

[Image © Paul Kolnik]

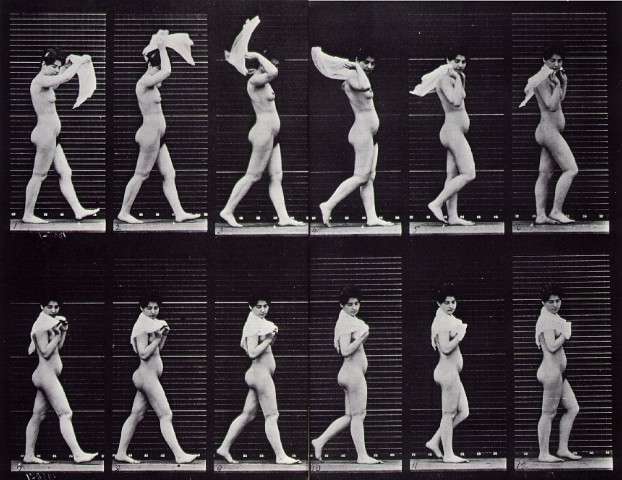

I learn from Oliver Sacks that neurologists use this phrase — the kinetic melody of movement — to describe the naturalness and fluidity of normal human movement. They call a halting, broken movement, caused by something like Parkinson's disease, a kinetic stutter.

As Sacks explains it, “When we walk, our steps emerge in a rhythmical stream, a flow that is automatic and self-organizing. In parkinsonism, this normal, happy automatism is gone.”

Dance elaborates on this natural kinetic “melody” in order to celebrate it, and it is something worth celebrating, as a sign of health and prowess, crucial to early human societies, especially ones based on hunting.

[Image © Paul Kolnik]

Like musical melodies, based undoubtedly on the pleasing qualities of human speech, especially in the unique voices of kinfolk and tribal allies, dance can become almost an end in itself — but it always retains an echo of the simplest kinetic melody, the song sung by any human body moving through space.

Sculptors, like Augustus St. Gaudens (above), and photographers like Paul Kolnik, who did the black and white images of the New York City Ballet here, can freeze motion in such a way that it implies the whole melodic arc of a movement.

When a filmmaker puts a frame around some part of the world, she is helping define a space, and thus helping us read any movement through it as a kinetic melody. Such melodies can, by the choreography of the movement, become almost symphonic, in the way classical ballet can. Good Westerns, which enlist the noble and elegant kinetic melodies of horses, are always symphonic in this way.

Every great filmmaker knows, if only intuitively, that she is really making a kind of music with her images.

Montana, August 1942. Some things don't change.

[Reproduction from

color slide. Photo by Russell Lee. Prints and Photographs Division,

Library of Congress]

With thanks to Amy Crehore at Little Hokum Rag . . .

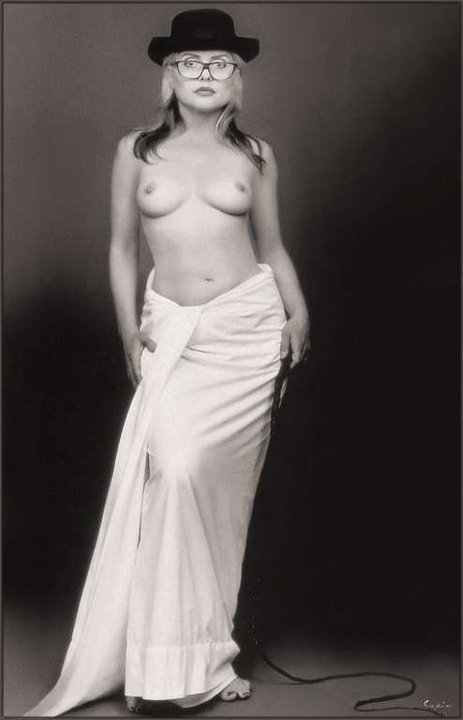

[Image © Langdon Clay]

There's always a creepy grin waiting for you at a Hampton Inn!

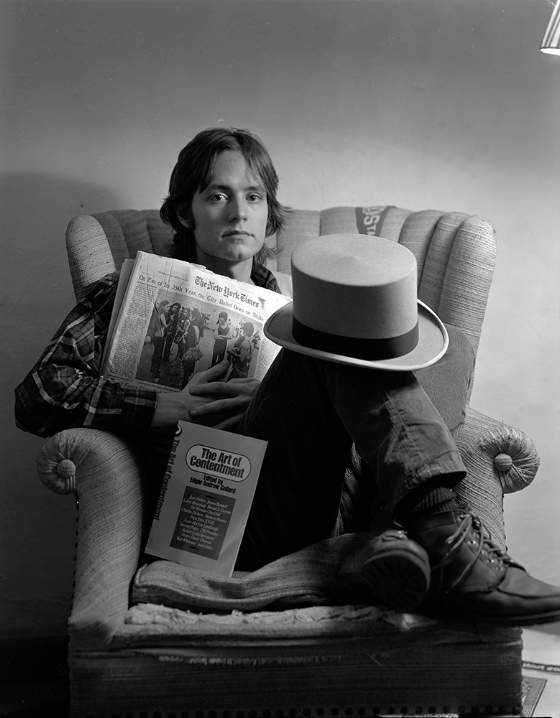

For my sixtieth birthday my friend Lang Clay sent me a print of the portrait above which he took of me in my loft on 21st Street in New York City around 1973.

He took it with an 8 x 10 view camera, with existing light using a long exposure. He was trying to recapture the aura of 19th-Century photographic portraits, in which the subjects always look uncannily composed and serene, as if posing for the gaze of eternity. This was in large measure due to the long exposure times required back then — one has to compose oneself to stay still for such a length of time.

The print Lang sent me was enormous — roughly 18 x 23 inches. A print that size really reveals the astonishing amount of “information” contained in a properly exposed 8 x 10 negative, which produces an almost 3D effect. The presence of my long-vanished self is intense in the image, and thus doubly melancholy and spiritual — I seem to be looking into my future with perfect calm, as the subjects of 19th-Century photographic portraits look into our time, a time in which they no longer exist.

In the portrait, I too have entered history — my twenty-three year-old self seems as far off as the Battle Of Antietam, as indeed in some sense it is. And yet it only tells part of the truth, because I feel, and in some real ways am, younger now than I was when the portrait was taken. (Below, another image from the same session.)

Time has roughed me up, but it has also opened me up — and that’s another sort of mystery photographs can illuminate, as they age along with us through the years.

I keep thinking of what my current self could tell that young man in the pictures — don’t be so afraid, don’t be so closed off, don’t be so cynical . . . time is your best friend. But I know him — he wouldn’t have listened to a word of it.