Some toys just are. Above is the Sideshow 12-inch action figure of Lon Chaney in his Masque Of the Red Death costume from The Phantom Of the Opera. I still can’t quite believe that somebody made this extraordinary thing, and that I own one.

Category Archives: Silent Movies

ANDREW WYETH AND THE SILENT CINEMA

[Renee Adoree and John Gilbert in King Vidor’s The Big Parade]

Reading an excerpt from David Michaelis’s biography of N. C. Wyeth in an

old Vanity Fair I came across an interesting passage. Writing about N. C.’s son Andrew, Michaelis says:

“Andy’s conception of army life had been formed by years of soaking up The Big Parade, King Vidor’s silent classic about three enlisted men in WWI, which N. C. had taken him to see as an eight-year old boy. ‘This film,’ Andrew later explained, ‘got into my bloodstream.’

Eventually he came to own a copy and would screen it four or five times a year all through his adult life. Forever linked to his deepest feelings about his father, certain frames of the film would form, without his realizing it, the basis for some of the most important images in his art.”

As an adult Andrew Wyeth eventually wrote a fan letter to King Vidor and the two men

met towards the end of Vidor’s life. Vidor made a short film about the encounter, the last film he ever made. In the film Wyeth remarks that when friends said they didn’t understand why he kept on watching The Big Parade after seeing it 180 times — literally — he replied, “You don’t understand my paintings, either.”

Two things struck me about this.

Firstly, it’s fascinating that a great artist like Wyeth, used to consciously analyzing visual images, should have created works which were unconsciously influenced by shots in a silent film. I think this speaks to the powerful ways cinematic images, particularly from silent films, can work on all of us unconsciously.

[A scene from Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt by Jean-Leon Gerome]

Secondly, I’ve always been struck by the influence of 19th-Century

academic painting on movies. The former were centrally concerned with

using spatial effects for dramatic and emotional purposes (again often

experienced in subliminal ways.) Movies, because they had greater

aesthetic resources in this area — i. e. movement in space by both

subject and camera — almost instantly spelled the end of academic

painting as a popular visual art form, and drove modern painters into

greater and greater abstraction.

The formal connections between 19th-Century academic painting and

movies is a subject that has hardly been hinted at in cinema studies to

date.

[Book illustration by N. C. Wyeth]

N. C. Wyeth kept the “cinematic” narrative-based academic style alive in

his book illustrations (as did Norman Rockwell in his magazine

illustrations) and N. C.’s son Andrew has been almost alone in keeping

elements of this style alive within the circles of modern “high art”, by

making the narrative element more ambiguous and blending the dramatic

representation of space (which is crucial to his work) with a more

pronounced abstraction of design.

In Andrew Wyeth’s obsession with The Big Parade we have a concrete example of the transmission of these oddly overlooked aesthetic connections.

[Trodden Weeds, 1951 tempera — © Andrew Wyeth]

SILENT SEX

Watching Mary Pickford’s films for the first time I was startled at how sexy she was. Even if she’s not your type, even if the curls make you cringe, it’s hard not to be vexed by her energy, her obvious intelligence, the expressive use she makes of her whole body. I have this same feeling about Lillian Gish. No matter how delicate and virginal a character she plays, she always moves sublimely, communicating subtleties but also controlled power by the very inclination of her body — something a great ballerina can do as well. This sort of thing gives a fellow ideas.

In a sense, the whole medium of silent film is permeated by this kind of frank though innocent sexuality. For adults, communicating emotion and character through the expressive power of the whole body is just inevitably bound up with the idea of sex, which is one reason why dancing has always been suspect in the Puritan mind . . . and great silent film acting is closely related to dance. Keaton is, ostensibly, a clown, and the characters he plays are rarely informed by any conscious awareness of their own attractiveness — but the raw animal lust he seems to inspire in some female silent film fans is impressive.

This may be one of the reasons I’m disconcerted by Pickford’s portrayals of children — Pickford’s sexual persona, which she really can’t lose, seems out of place in a pre-sexual being.

It occurs to me also that this may explain the vague “creepiness” some people feel about Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. He just moves so beautifully, so exquisitely, that perhaps he arouses unconscious thoughts which people, women especially, don’t want to associate with that particular physique.

A more extreme version of this reaction, in a more buttoned-up age, might also explain, on a subconscious level, some of the antagonism towards Arbuckle, the immediate presumption of guilt, when he got caught in a sex scandal. It would be impossible to imagine such a scenario in the case of John Candy or Chris Farley, because they simply weren’t capable of the kind of carnal grace Arbuckle had at his command.

Most modern actors have lost this means of suggesting a complex sexuality by sheer physical carriage, which is why they’re forced to expose themselves, or say naughty things, to grab a viewer’s attention in that regard. Pickford’s little jig in Tess Of the Storm Country got the job done for me.

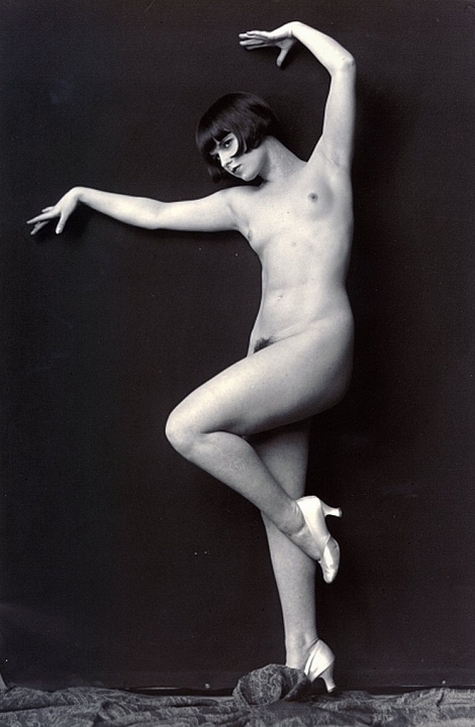

PANDORA’S BOX

Pandora’s Box, the film Louise Brooks is best known for, is one of the sublime works of cinema, not least because of her performance init.

It is not exactly a film adaptation of the famous play by Franz Wedekind on which it is nominally based — it is better appreciated as what it calls itself, a “variation on themes” from Wedekind’s work. Wedekind created in his central figure of Lulu an almost mythological incarnation of the terror the feminine inspired in late Victorian men, who simply didn’t know how to relate to women outside the collapsing domestic structures of modern industrialized societies. Wedekind’s Lulu was a calculating vamp, an anarchic force, unrestrained by the old female roles, and thus could be experienced as an alien and malevolent power.

Pabst’s and Brooks’s Lulu is something else again. Her destructive power is not defined by her deviance from old female roles but by the utter collapse of manhood around her, by the failure of men to adapt to the new empowerment of women. The crucial event intervening between Wedekind’s play and Pabst’s film was the cataclysm of WWI, which confirmed not just the collapse but the inherent weakness, the dry rot at the heart of the 19th-Century European patriarchy. From a post-WWI vantage, Pabst, by instinct or calculation, realized that blaming women was not really an answer or a solution to the failure of modern manhood.

Pandora’s Box shares aspects of an attitude that wouldn’t find its way into American film until after the cataclysm of WWII, specifically in film noir, where a sense of the futility of male power slammed head-on into the contingent terror of the female, the femme fatale.

But Pabst’s film is more mature, ahead of its time even, in making Lulu’s female power innocent, neutral, a mere fact of life, which men simply have no resources to engage on equal terms.

In Pabst’s film men destroy each other and destroy themselves trying to engage Lulu’s existential sexuality. They try to commodify her, reduce her to images, trade her for money. They fail at every turn to diminish her. And yet they must keep on trying, since they can’t have meaningful intercourse with her as she is, and this is a constant reminder of their own impotence. Early in the film Lulu tells her current benefactor, “The only way to get rid of me is to kill me.” Her sexuality cannot be dismissed any more than it can be engaged — it can only be destroyed.

This explains the curious ending of the film, in which Lulu meets a contemporary version of Jack the Ripper in London and is instantly drawn to him. He is in a sense the only

honest man in the whole tale — he worships Lulu, like all the rest of the men in her life, knows he’s no match for her, knows the only way he can deal with her is by killing her. Which he does — but not before paying touching tribute to her majesty, crowning her with Christmas mistletoe, in images that glow with tenderness and sacramental mystery.

Lulu almost seems to acquiesce in her own sacrifice — a final extension of the detachment she displays throughout the film. It’s not her job to tell men how to be men — she can only observe the failures of their doomed attempts to figure it out for themselves. She observes with interest, certainly, sometimes with awe, but never with a sense of personal responsibility. Compromising her female essence to accommodate the impotency of men is not a solution for her, or for her lovers.

Brooks’s incarnation of this role is brilliant in the extreme, one of the finest pieces of acting in all of movies. Her work is neither minimalist nor merely naturalistic — just “being herself” . . . whatever that might mean in the utterly artificial, high-pressure context of a film set. Pabst was clearly drawing on aspects of Brooks’s own personality in the film, but the result is a “created” character of great complexity, one which never resolves itself into any conventional type or relies on any conventional response. Brooks’s performance has inwardness and mystery, as Shakespeare’s characters do, as Chaplin’s and Keaton’s characters do.

Pabst’s and Brooks’s Lulu is almost unique in modern art — neither a demonized icon of male fear nor an idealized icon of female ambition. She doesn’t want what men have — she wants men to recover what they once had. She wants partners. Finding none, abandoning hope, she resigns herself to oblivion, but not before accepting, graciously, Jack’s grotesque and pathetic tribute to what has been lost.

RADICAL AESTHETICS

Jean-Luc Godard has credited much of the impetus of the French New Wave to the fact that the young filmmakers who created the movement had spent so

much time watching silent movies, courtesy of Henri Langlois, the great

film collector and founder of the Cinematheque Francaise.

Godard believed that the radically alien aesthetic of silent movies allowed

these young filmmakers to see the medium with fresh eyes, freed from

the expectations of current style enforced by the habits and dictates

of the French national film industry and the Hollywood studio system.

Godard also said that the principal idea of the New Wave was to get everybody

out of filmmaking who didn’t belong in filmmaking — to wrest control

of the medium from corporate functionaries and state bureaucrats and

return it to those who actually created movies.

Today, when corporate control of popular movies is nearly absolute, and

forcing its range of possibility into narrower and narrower limits, a

study of silent cinema is even more likely to inspire the sort of

resistance that will be required to rescue movies from corporate

perversion and reclaim them for humane expression on behalf of the

culture at large.

D. W. Griffith once said, paraphrasing Joseph Conrad, “What I’m trying to do after all is make you see.”

Look.

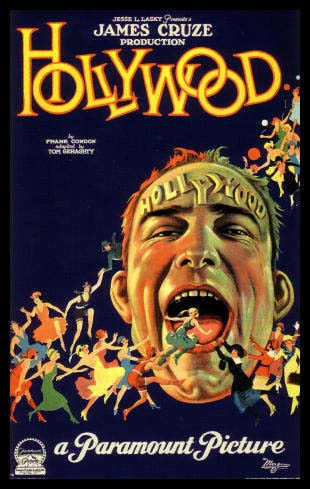

LOUISE BROOKS

2006 marks the 100th anniversary of Louise Brooks’s birth. It’s been

celebrated by the release of a cool new picture book about the star,

“Louise Brooks: Lulu Forever”, by Peter Cowie, and a special DVD

edition of her most famous film, “Pandora’s Box”, put out by Criterion,

with lots of extras.

Brooks was, like Garbo, a creature who had her being on film — her way

of moving through cinematic space could transcend the films that tried

to contain her, transcend the normal conventions of “screen acting”.

Early in her career she played second lead in a mediocre comedy called

“The Show Off”. She doesn’t seem to be part of the film at all — she

looks like someone who has wandered onto the set while the cameras were

rolling and decided to stay and observe the curious behavior of the

people around her. She appears to have found this behavior only

vaguely amusing, and in this delivers a wise critique of the film from

within the film itself. The effect is bizarre.

G. W. Pabst used her uncanny mixture of detachment and sensuality to

brilliant effect in “Pandora’s Box” — he was one of the few directors

who seems to have realized that a film had to defer to her phenomenal

screen persona or risk evaporating around her. It’s a film you should

watch at least once this year.

Happy birthday, Lulu.