Category Archives: Silent Movies

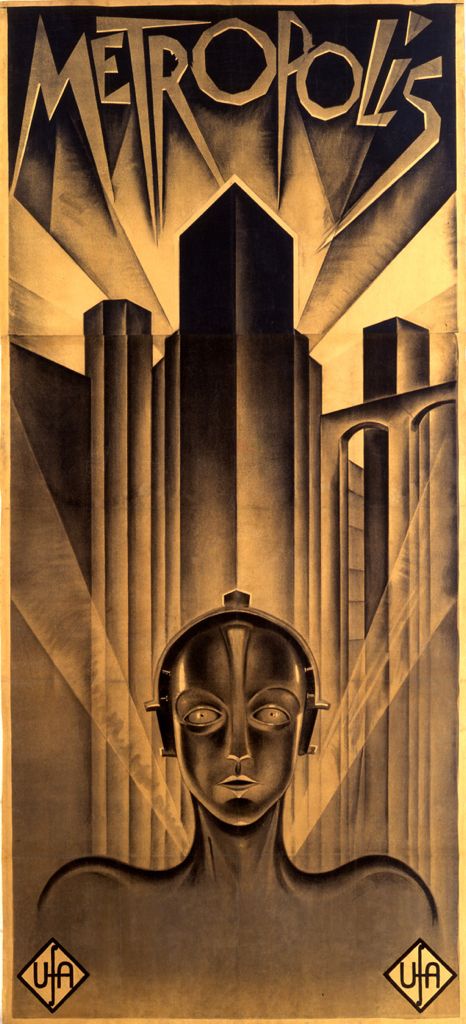

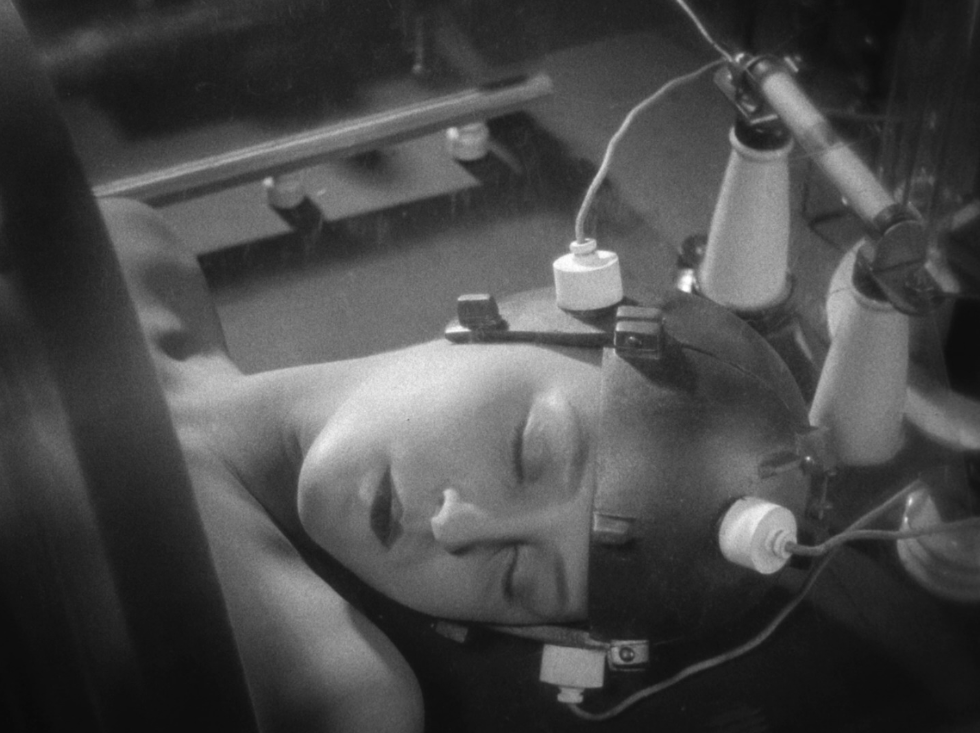

FRITZ LANG

A frame from Metropolis above (click on the image to enlarge), and Spione below.

William Ahearn offers a useful, comprehensive film by film survey of Lang’s German work here — Meditations On Fritz Lang.

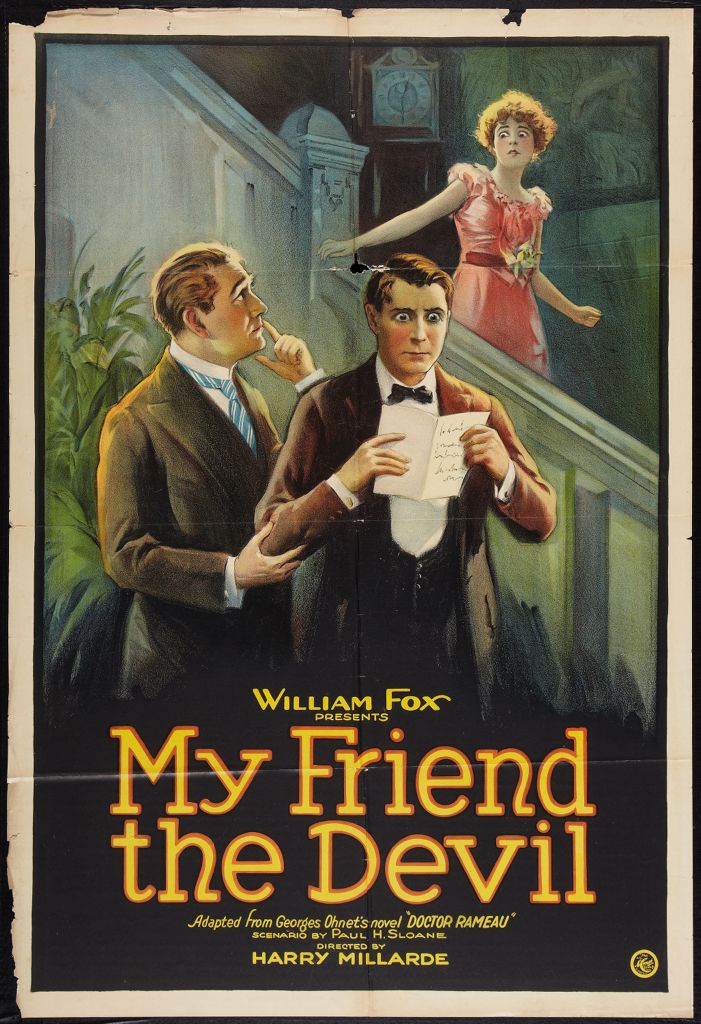

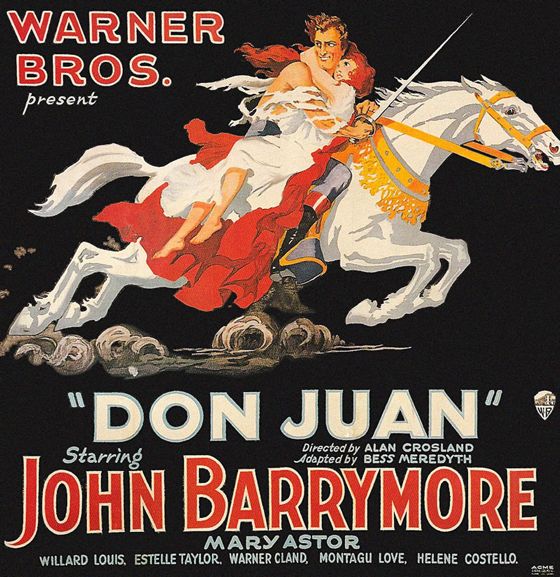

A SILENT FILM POSTER FOR TODAY

A NEW KIND OF SEXUALITY

Characters in popular art who make fun of sex, of their own sexuality, while still being deeply and powerfully sexy strike me as peculiarly American — I can't think of any examples that originated in other countries.

The English music hall created a kind of ditzy sexpot, best exemplified by Beatrice Lillie (above), but the ditzy sexpot had a very restricted erotic appeal — she tried to appear accidentally sexy, and was never sexually threatening in any way. That was her charm. The “naughty schoolgirl” figure crosses cultures, too, but her mask of good-natured innocence is just that — a mask, behind which to deliver erotic innuendo.

But America came up with something new — and as far as I can tell, Clara Bow was its first example. She was frankly, unabashedly sexual, often in a way that threatened buttoned-up men, but she had a way of laughing it all off as a lark — as something not to be taken too seriously.

You can see traces of this attitude in the great female blues singers of the early 20th Century, like Bessie Smith, but Smith knew that she was being bad — her tossed-off double-entendres had a leering quality, suggesting a down and dirty smirk.

Bow had none of this — to her there was nothing down and dirty about sex at all. It was just about having fun, and if it was the most important thing in life, that was only because having fun was the most important thing in life. Her overt but always skillful and imaginative flirtatiousness honored the game of flirtation, accepted it for what it was — if men didn't understand it, or know how to play it well, that was their problem. It gave her an advantage which she cheerfully exploited.

Bow was different from the wise-cracking females in screwball comedies, who played the game with an edge of cynicism, somewhat resenting men for their dull-wittedness, even if they ultimately forgave them for it. Stanwyck's character in The Lady Eve (above) is the paradigm for this type.

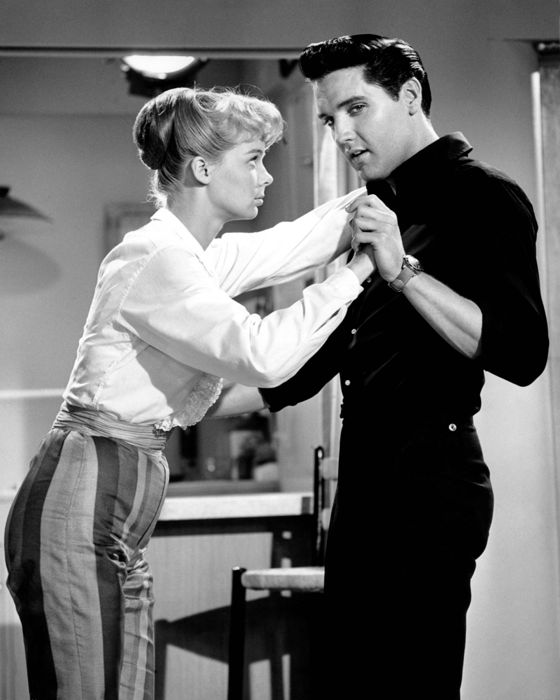

Bow's true successors in American culture were Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, who were sexy, knew they were sexy, laughed at their own sexiness while flaunting it without shame, in a state of paradoxically pure innocence about it.

They could be ironic but never, ever cynical.

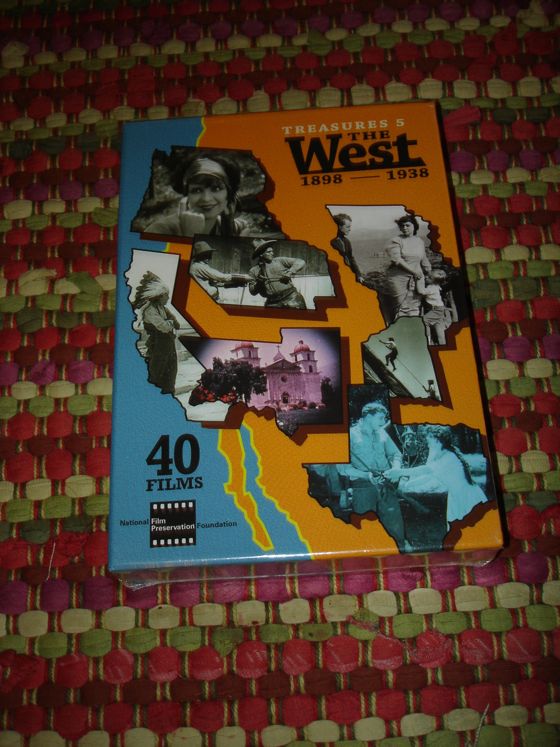

The new DVD set Treasures From American Film Archives: The West has a stupendously good print of the silent film Mantrap (above) in which Bow definitively realized the new type of sexuality she pioneered. It's one of the greatest and most electrifying performances in the history of cinema, a performance that led to her being cast in It — to be seen as “The 'It' Girl”. They had to call it “It” in her case, because there was no existing word for what she had — no previous form of sex appeal applied. It was a new kind of it.

[I have never seen a still photograph of Bow that really captures her screen persona. The studio publicity photographers tried to fit her into familiar categories — glamor queen, vamp, flapper — none of which came close to evoking what she did on screen, which is hard to evoke in words, too. You just have to watch her best movies — she herself thought that Mantrap was the best of them all — and marvel.]

SHOOTING COWBOYS AND INDANS

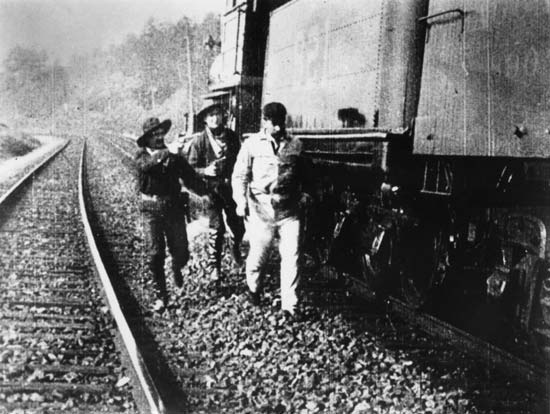

Although the first truly important narrative film made in America, The Great Train Robbery from 1903, was a Western of sorts, it took about five years before the Western-themed film resolved itself into a recognizable genre. It was a wild and wooly ride, which the form almost didn't survive. Like The Great Train Robbery, early Westerns focused on violent crimes. They modeled themselves on sensational Western dime novels and appealed mostly to kids and male working-class moviegoers — and to foreign audiences. When producers and distributors decided to court a higher class of clientele, including women, the Western came to seem unsavory, driving the better sort of folk away from the fancy new movie palaces that were gradually supplanting the storefront nickelodeon.

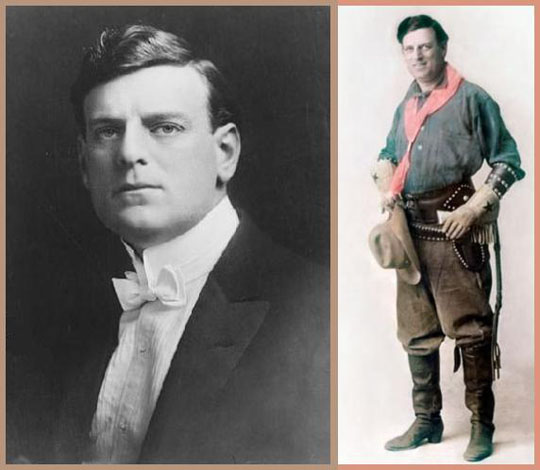

Gilbert “Bronco Billy” Anderson (above), who had played three bit parts in The Great Train Robbery, rode to the rescue by creating a Western hero who appealed to all classes and to women. “Bronco Billy” might start off as a bad man but his heart was always in the right place and he always ended up tamed by and defending conservative social values, usually personified by a beautiful and virtuous woman.

When Anderson lost interest in Westerns, and movies in general — his dream was to become a theatrical impresario — William S. Hart (above) was there to fill his boots. Hart played a tougher and more taciturn Western hero but like Anderson always came around to the defense of traditional values, religion and social order.

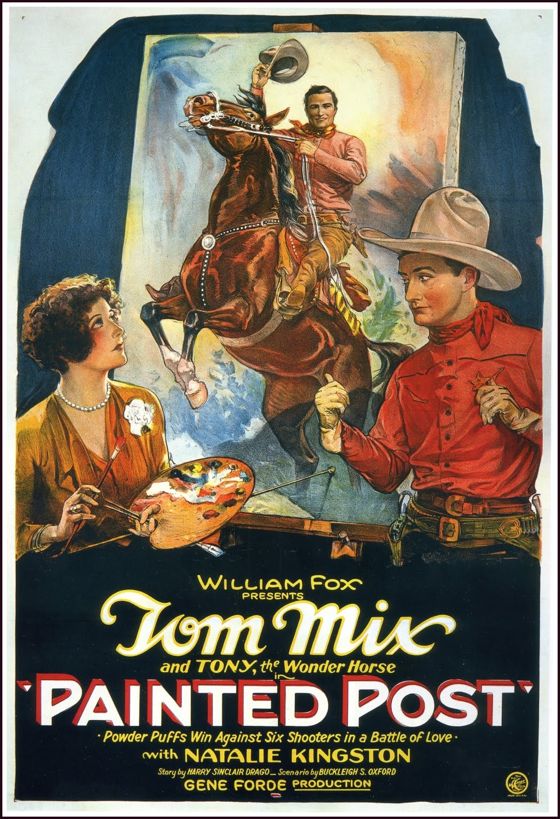

In the 1920s, an era of industry consolidation, the studios generally gave up on Westerns that might appeal to everyone. The B-Western was born, marketed once again to kids, to working-class males and to foreign audiences. These constituted a reliable though limited base for Westerns, which had to be cheap and formulaic to make money — but they made a lot of money on that basis and were a major source of studio profits. They produced big stars like Tom Mix, above, but stayed lean and mean where budgets were concerned.

The wonderful book by Andrew Brodie Smith pictured at the head of this post tells the tale of how the Western was born and how it evolved into a genre — restricted in form by the 1920s but still vital and immensely valuable to the industry. Well-researched and written, it's essential to understanding the role and nature of Westerns in the earliest years of cinema.

TREASURES WEST

You can't imagine how excited I am about this . . .

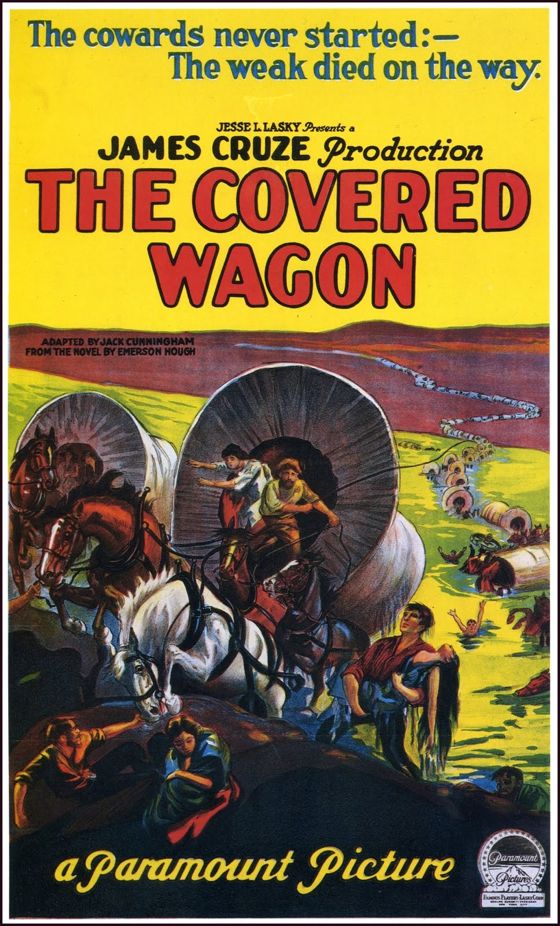

A SILENT FILM POSTER FOR TODAY

A SILENT WESTERN MOVIE LOBBY CARD FOR TODAY

Directed by John Ford, 1926.

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

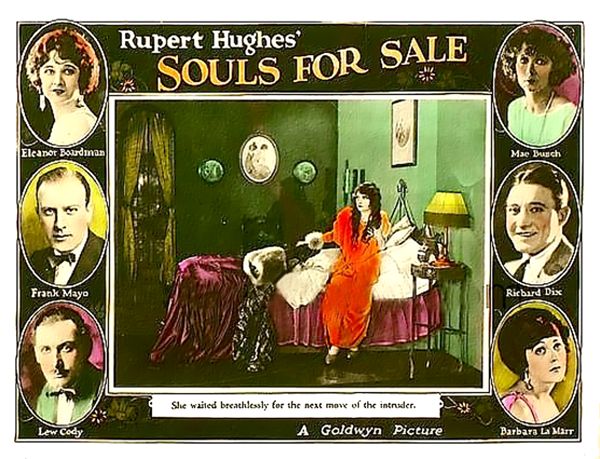

SOULS FOR SALE (1923)

Souls For Sale is, I think, the second best movie ever made about Hollywood, and makes a perfect pendant to the best, Sunset Boulevard. Souls For Sale is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of Eden, just as Sunset Boulevard is a portrait of Hollywood as a kind of purgatory.

The sheer, delirious joy of movie-making before the studio bean-counters took full control of the industry is present in Souls For Sale. The film tries to present a balanced view of Hollywood from the other side of the camera, but it can't really — it's too swept up in the nuttiness and energy and attractiveness of the movie folk.

The film features a lot of cameo appearances by real Hollywood stars and directors of the time. One of them is especially poignant. We get a glimpse of Erich Von Stroheim at work on a set for Greed. We know now that he was creating one of the greatest works in the history of American art, but the cameo was filmed when the production still belonged to Sam Goldwyn's company. Before Greed was completed, that company was sold to Metro and the production thus came under the control of Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, who, in an act of unspeakable thuggishness, decided to mutilate Von Stroheim's masterpiece, to send a message to the rest of Hollywood's talent — you are no longer in control here . . . the industry you built now belongs to thugs like us.

In Souls For Sale you can see what was lost in that transfer of power — the giddy excitement of a new art form still in the hands of the artists who created it — just as in Sunset Boulevard you can see the rot and decay of that erstwhile Eden under the influence of the thugs. It's no accident that Louis B. Mayer was outraged by Sunset Boulevard. It was an epitaph for everything he personally destroyed.

The giddiness of that time before the thugs took control informs every moment of Souls For Sale. It's a thoroughly self-reflexive work of art, which pretends to examine how the dream world of the movies is constructed while itself infected with the very dreams it pretends to examine. This tension in its point of view is quite deliberate and often played for laughs, though it more often results in a kind of surreal poetry.

The story opens on a train racing through the desert on its way to Los Angeles. A young bride on her wedding night has suddenly become revulsed by the man she's married and jumps off the train at a remote watering station. She wanders hopelessly through the desert until she comes upon . . . an Arab sheik on a camel, who rescues her from death. He's an actor on location with a film crew, making a movie.

So we have moved with the mad logic of a dream from melodrama to costume drama to comedy. The whole film navigates a similar dream landscape — it's a hall of mirrors from which we never emerge. At the climax, an intertitle informs us that a real hurricane is threatening to wreck the artificial storm set up for the climax of the film within the film — and we proceed to watch the “real” artificial storm ruin the “fake” artificial storm.

If Jorge Luis Borges had ever made a movie, I suspect it would bear an uncanny resemblance to Souls For Sale.

The film was based on a novel by Rupert Hughes and also directed by Hughes (who was Howard Hughes's uncle.) He was a successful playwright, novelist and historian who directed seven films between 1922 and 1924 — then went back to writing. Souls For Sale is a handsomely mounted and photographed production, with fine performances, and it has a few images of real grace and power. Hughes was either exceptionally well-supported by Goldwyn's studio technicians or else he had a genuine gift for directing. In either case, it would be interesting to know why he abandoned the craft.

He left us a minor masterpiece, though — a vision of what the movies might have been without “boy geniuses” like Irving Thalberg and “benevolent patriarchs” like Louis B. Mayer.

A WESTERN MOVIE POSTER FOR TODAY

Nobody said the way to Las Vegas was going to be easy . . .

HAROLD LLOYD

Check out Matt Barry's blog The Art and Culture Of Movies for one of the best appreciations of Harold Lloyd ever:

The Dilemma Of Harold Lloyd

PARADISE RECLAIMED

[Photo © 1960 William Klein]

An excerpt from a 2000 profile of Jean-Luc Godard by Richard Brody in The New Yorker:

During our interview, Godard referred

to the New Wave not only as “liberating” but also as

“conservative.” On the one hand, he and his friends saw

themselves as a resistance movement against “the occupation of the

cinema by people who had no business there.” On the other, this

movement had been born in a museum, the Cinémathèque: Godard and his

peers were steeping themselves in a cinematic tradition — that of

silent films — that had disappeared almost everywhere else.

Thus, from the beginning, Godard saw the cinema as a lost paradise that

had to be reclaimed.

If love of the cinema of the past doesn't point the way to new, revolutionary

work — as love of ancient Greek art sparked the innovations of the

Renaissance — then it's just an exercise in nostalgia.

In other words, the cinema of the past can be alive as a cultural force, as it

was for the young French cinéastes of the Fifties, just as ancient Greek

art was alive for the artists of the Renaissance.

The parade has not gone by — it may even be passing this way:

VISUAL MICRO FICTION

The first story films were very short — either little gags that could last less than a minute or narratives lasting about ten minutes. There's a reason for that. Because movies were a new form, novelties, they fell into story frames that audiences were already familiar with — newspaper cartoons and comic strips, which could be read in less than a minute, and vaudeville skits, which lasted about ten minutes. These familiar forms helped audiences fit story films into their habitual patterns of consuming entertainment.

In this era, movies and comic strips fed off each other, expanded each other's boundaries.

The first truly sensational American story film, The Great Train Robbery (see the frame grab above), appeared in 1903. There had been story films before this, or anecdotal films with narrative qualities, but The Great Train Robbery was so popular that it almost singlehandedly created the new market for story films. In a short time they had replaced gag films and actualities as the preferred cinematic form.

D. W. Griffith made his first ten-minute short in 1908 and at once began expanding the expressive range of the short story film. In 1909, the first regular comic strip, Mutt & Jeff (above) began appearing in newspapers. There had been multi-panel strips before this, along with single-panel cartoons that told little stories, but Mutt & Jeff signaled the emerging dominance of the strip. Just as single-panel cartoon gags had provided a template for early gag films, so the longer story films helped pave the way for the popularity of the multi-panel strip.

In the YouTube era of Internet cinema, we are about where projected movies were before The Great Train Robbery. The next step will probably be very similar to the next step projected movies took — into the territory of the newspaper cartoon and comic strip and vaudeville skit, all of which can be studied profitably as exercises in micro-fiction. The idea that Internet cinema can leap from the cute pet or baby video into feature-length narratives is a fantasy. People will eventually consume feature-length narratives via the Internet, but what happens between now and then will be intensely exciting. This is when the shape of cinema to come will be determined.

SILENT MOVIE SNOW

Lillian Gish, Way Down East.