When new technologies appear, the instinct is to try and figure out ways to make them the vessels for existing content. But new technologies usually need a new kind of content — or old content wholly re-imagined.

When it became possible to distribute movies on the Internet, everybody tried to figure out how aging, worn-out Hollywood content could be shifted over to the new venue and monetized. It was an effort doomed to fail. Content can never be considered apart from the means used to distribute it, and thus the ways it is consumed.

What we need to do is look at what kind of movies are working on the Internet, and proceed from there. What's working are short comedy bits, short sexy images and actualities — real-life anecdotal videos of a cute or startling nature.

It's strikingly like the content that first made movies popular, when the technology of projected film first hit the scene at the end of the 19th century. Films were novelties then — people had no way conceptually of consuming them as self-contained works. So they were shown as peep-show attractions in arcades or as interludes on vaudeville bills. What people responded to were . . . short comedy bits, short sexy images (a dancer showing a bit of leg was soft porn back then), and actualities, real-life anecdotal films of a cute or startling nature.

Plus ça change, huh?

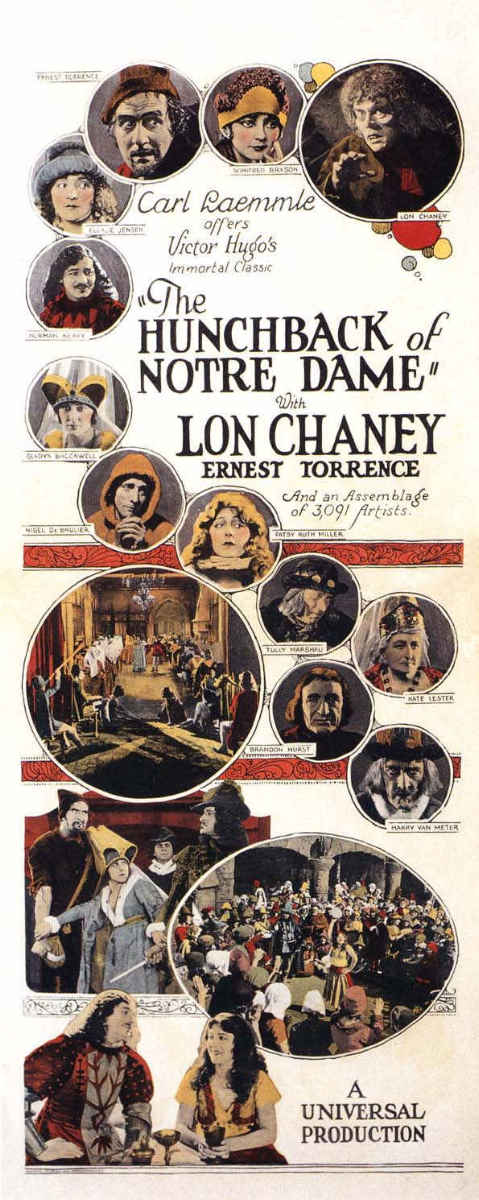

But people soon grew tired of these snippets. They wanted longer, more coherent pieces, which meant that they wanted stories. But it wasn't possible to jump straight to any existing story form. Attention span still could not support film stories the length of plays, much less novels, or even short stories. Ten minutes was the absolute limit of attention one could count on from an early film viewer — about the length of a vaudeville skit. So a whole new form of storytelling was developed — one that incorporated short comedy bits, sexy stuff and documentary footage (of trains, for example.) But now these were integrated into a narrative.

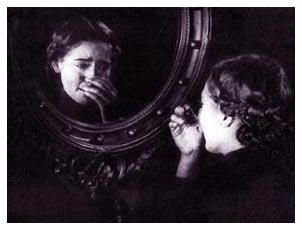

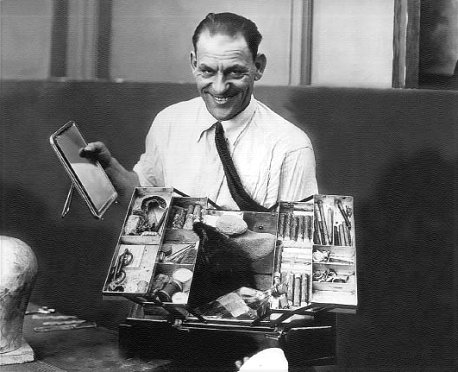

Audiences had to learn to absorb these short narratives before they could be expanded into feature-length film narratives — into an evening's entertainment. It happened remarkably fast, primarily because the ten-minute and then the twenty-minute form was developed with such brilliant invention by storytellers like Griffith. The density of content and suggestion in Griffith's one-reelers and two-reelers, and the extraordinary beauty of his images — like the one above from The Country Doctor in 1909 — eventually made it clear (to some) that movies could hold an audience's attention for even longer than twenty minutes.

Filmmakers need to start anticipating what story forms are going to work on the Internet. There will not be a straight jump to feature-length narratives, or even half-hour narratives. Even the length of a ten-minute vaudeville skit is probably too long. What's needed are stories no longer than a cute cat video.

Can stories, real stories, be that short? Of course they can. Micro-fiction is as valid a form of fiction as any other — if it is dense with content and suggestion, if it can conjure up whole worlds beyond the frame of its images and brief running time.

Hemingway was once challenged to write a six word story. He came up with this — “For sale, baby shoes, never used.” That tells a real story, and a good one. It resonates in the mind and in the heart, like any good story. The micro-movies that will introduce real narrative content to Internet cinema will have to learn that kind of dynamic compression, and they will have to be told in images of genuine beauty, depth and inventiveness — there will be no room for the slick, throwaway non-images of the current Hollywood cinema, which have to be hurled past us at lightning speed because they would not reward close scrutiny.

This path is really the only way forward for filmmakers of the Internet era. It may seem like re-inventing the wheel, but filmmakers of the nickelodeon era were also re-inventing the wheel when they tried to figure out how to put over a grand Biblical epic in ten minutes. They seem to have had an awful lot of fun doing it, though, and in the process they created a new art form.

An essay like this can't really suggest the kinds of films I'm proposing, but my friend Jae Song is currently directing a series of movies in New York — I call them Majestic Micro Movies — which will make the whole thing clearer. You'll be able to watch them soon — here, there and everywhere.