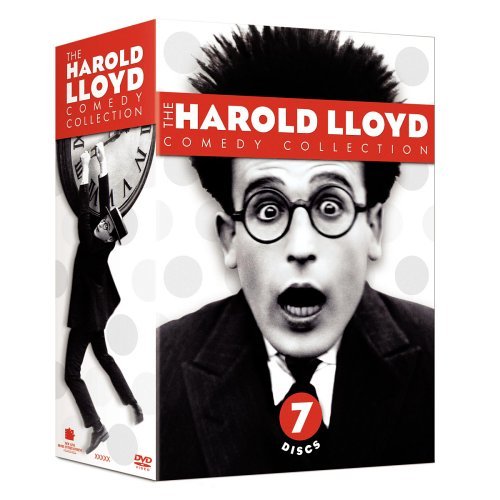

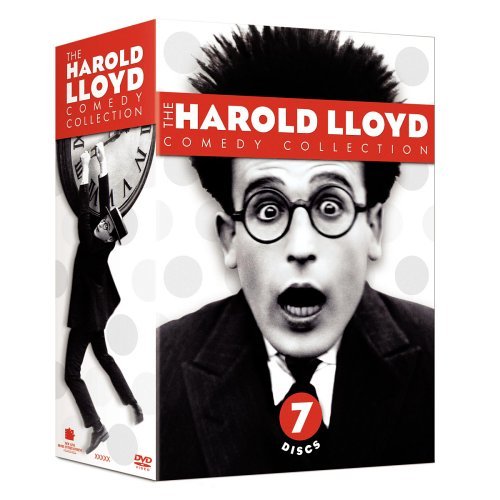

The recent Harold Lloyd box set is both a miraculous treasure and a

daunting challenge.

Like most people of a certain age I got to know the work of Chaplin and

Keaton slowly, in bits and pieces, over the course of many years,

starting with the 8mm Blackhawk versions of the Chaplin Mutuals my

friends and I collected in high school, continuing through occasional

college campus screenings and the theatrical reissues of the 60s and

70s.

This gave one time to absorb the bewildering genius of these two great

artists.

Lloyd’s most important films were much harder, in many cases

impossible, to find. Before the release of the Lloyd box set I think

I’d only seen Haunted Spooks and Safety Last — enough to know that

Lloyd was a force to be reckoned with but hardly enough to appreciate

the full measure of his achievement.

Now, getting so much of Lloyd’s work all at once, in the fine transfers

on the new set, I find myself a bit overwhelmed — it’s really too much

to react to in detail — but my first impressions of it go something

like this . . .

Having watched each film in the set at least

once, it’s clear to me that Lloyd was not only a filmmaker of equal rank with

Chaplin and Keaton, but of equal rank with any filmmaker in the history

of movies. With such an artist, it makes almost no sense to

compare and contrast him point for point with his peers — one loves

him for his unique genius.

The center of that genius was Lloyd’s instinctive love for and

understanding of the film medium. He didn’t comment on it as part of

his method, the way Keaton did, but he used it with unabashed joy and

energy, and with a supreme mastery that’s still dazzling.

There is hardly any film in the new set that doesn’t have its

exhilarating moments, though this is not to say that all the films

succeed equally as unified works. What distinguishes one from the

other is a central problem Lloyd seemed to wrestle with creatively

throughout his career — the nature of the character he’s playing and

its place in the particular story he’s telling.

The “glasses character” is an everyman in the sense that he presents

himself, whether rich or poor, urban or rural, as a fellow of ordinary

capacities who is impelled at some point to do extraordinary things.

These “extraordinary things” were clearly what inspired Lloyd the

filmmaker most centrally. He usually thought up the final chase or

thrill climax for his films first, and then worked backwards to create

a narrative rationale for the action in that last reel.

Lloyd’s last reels are almost always brilliant — the narrative rationales vary greatly in kind and quality and determine the success or failure of the films as stories, as whole works.

As a general rule I would say that the films in which the glass

character is motivated primarily by a desire for success, financial or

social, are the least satisfying, even when that desire for success is

linked to the character’s desire to win the approval of a girl. These

films of course reflected the values of a different time, the Roaring

Twenties, in which unbridled material ambition was seen as a primary

American virtue, but the attitude struck even some observers of the

time as shallow and disturbing, and it hasn’t aged well.

The “romantic” premise of both Safety Last and Girl Shy is that the

glass character must achieve financial success in order to win the hand

of his beloved. This tends to undercut the “romance” angle

considerably — can’t true love rise above a concern for cold hard

cash? — and turns the “hero’s journey” into the hustler’s

progress. (In these films we see the genesis of James Agee’s brilliant

observation about Lloyd — he “wore glasses, smiled a great deal, and

looked like the sort of eager young man who might have quit divinity

school to hustle brushes.”) The last reels of both these films are so

exciting cinematically that we hardly remember what got us to them, but

the excitement is curiously unemotional, like a ride on a

roller-coaster.

Similarly, the desire of the freshman in the film of that name to be

liked by people who are frankly presented as jerks strikes an odd

note. Lloyd knew that social embarrassment, and even social

humiliation, are good material for gags, but how can one be seriously

embarrassed or humiliated by jerks unless one is a bit of a jerk

oneself? At best this tends to undercut our sympathy for the freshman

— at worst it puts us squarely in the camp of the jerks who are laughing at him,

too. The emotional set-up is off-kilter in The Freshman, as is the

emotional pay-off. We’re told that the protagonist needs to be

himself, stop trying to gain his self-esteem from the opinions of

others — but then he impersonates a football player and achieves

spectacular success on the field as thousands cheer. The episode is

wonderful, hilarious, magical even — but it doesn’t jibe emotionally

or thematically with the rest of the film.

I would argue that Lloyd’s greatest films, his masterpieces, are the

ones in which the glass character has something more interior to do

than gain wealth or status — who has some inner weakness or

selfishness to overcome before he can win the day and be worthy of his

girl.

These masterpieces would include Why Worry? and For Heaven’s Sake,

in both of which Lloyd plays a character who’s already rich but lacks

inner grit and empathy until spurred on to them by the leading lady.

They would include The Kid Brother, in which the protagonist needs to

grow up and establish his own identity in the face of obstacles both

domestic and foreign. None of these films has a last reel as awesome

as the ones mentioned above, but they’re awesome enough, and to me more

satisfying, because they reflect deeper emotional transformations in

the film’s central characters.

Because the glasses character isn’t a clown, doesn’t have a clown persona

that migrates more or less intact from film to film, Lloyd always had

to ask who his protagonist was, what he wanted, this time out. The

nature of the answers he came up with ultimately determined the overall

quality of the films as satisfying stories, as unified works of art.

Watching the business on the building in Safety Last or the

race-to-the-rescue to end all races-to-the-rescue in Girl Shy, you won’t be troubled with

such reflections — they become, for the moment, quite irrelevant. But the

next time you come back to the films — and Lloyd’s films are films

that can be watched with profit over and over again, if only for their

sublime cinematic inventiveness — you may feel differently, and long

for the more modest but more moving pleasures of Why Worry?, For

Heaven’s Sake and The Kid Brother.