Click on the image to enlarge.

Category Archives: The Funny Papers

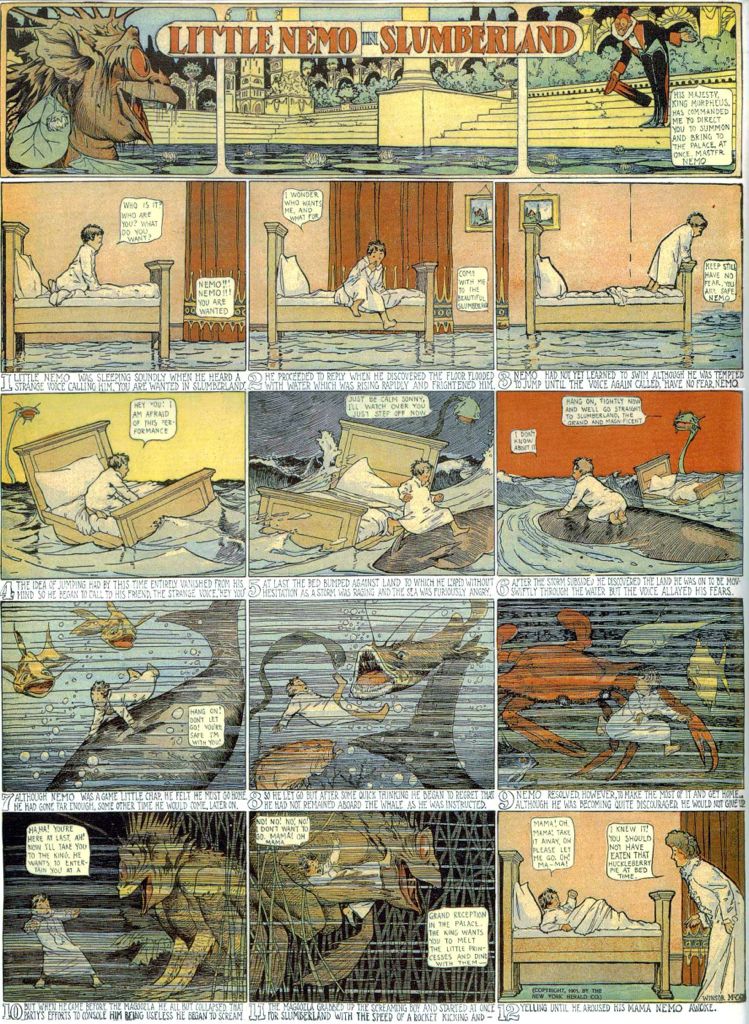

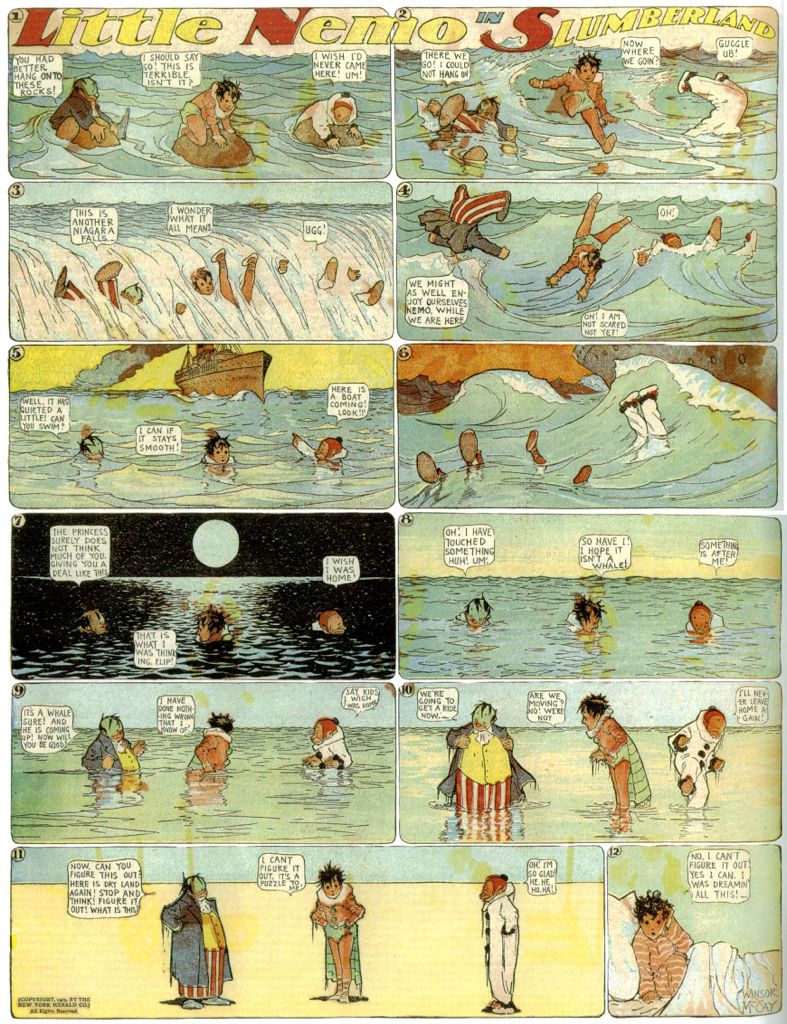

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE NEMO

Magnificent is the word that comes to mind when describing Winsor McCay’s comic strip panels. He created impeccably detailed images with great depth recording wildly imaginative visions of a fantasy world as delightful and transporting as any in the history of art.

As a strip, Little Nemo is whimsical rather than funny. The action takes place within the individual panels, not in their sequences — the visual storytelling is thus not dynamic in the cinematic style of most great comic strips. For the most part we move from panel to panel as through they were linked by cinematic dissolves from one tableau to the next — but the tableaux can take your breath away.

They work as renditions of seductive dream spaces, that invite you to enter them physically, and also as graphic designs of great sophistication and elegance. Their aesthetic appeal is inexhaustible, even if you prefer strips with more narrative momentum.

They need to be seen in large-scale reproductions in order to be fully appreciated and relished. (The scans reproduced here don’t even begin to do them justice.) Fortunately Sunday Press Books has published two of its gargantuan volumes presenting selections of the Sunday strips in the size of actual newspaper pages, as they first appeared, and Taschen Books has published a somewhat smaller but still enormous single volume collecting all the Sunday pages.

Together they document one of the supreme achievements of visual art in America.

Click on the images to enlarge.

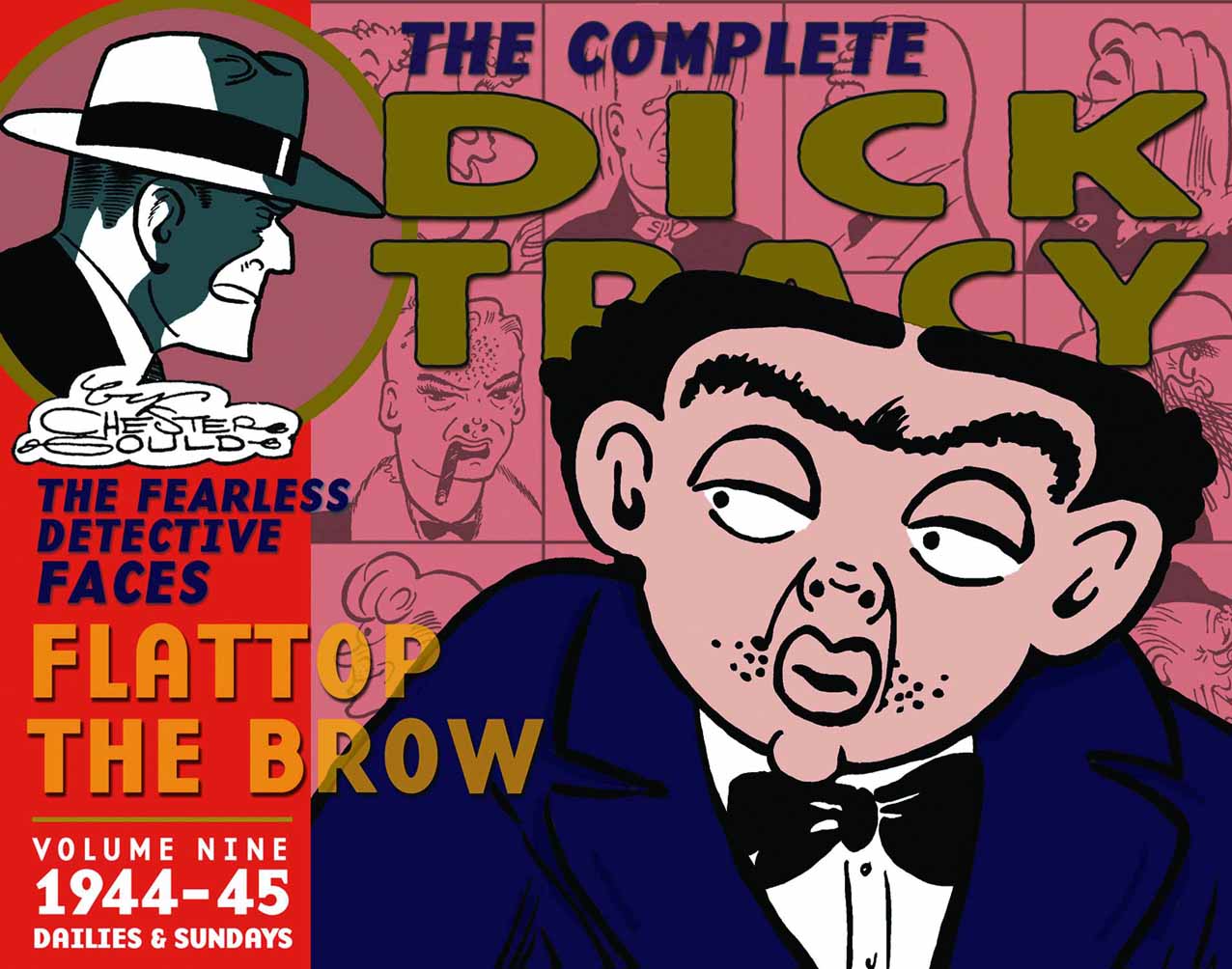

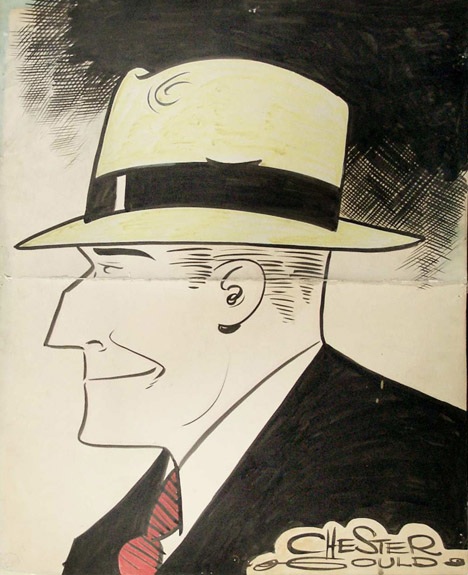

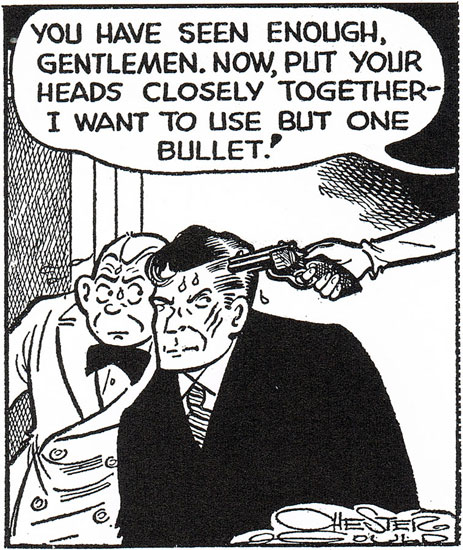

THE FUNNY PAPERS: DICK TRACY

Dick Tracy is a hard comic strip to love but an easy one to get addicted to. Its author Chester Gould was attracted to the grotesque, an attraction he indulged more and more outrageously as the strip progressed through the decades.

Tracy had a faintly grotesque look from the beginning — he was a hard edged caricature of a tough police detective — even though the characters around him looked relatively normal. The hard edges signified a relentless hatred of criminals and also a fierce independence — he always did things his way and rarely let his fellow cops in on his investigative stratagems.

There’s something grimly fascinating about him and about the dark underworlds he has to penetrate in order to solve his cases. The strip started out as a fairly conventional police procedural with an unconventional protagonist. It would eventually become stranger, with fantastical villains and plots. It was always lurid, to one degree or another, and that constitutes its vaguely perverse charm.

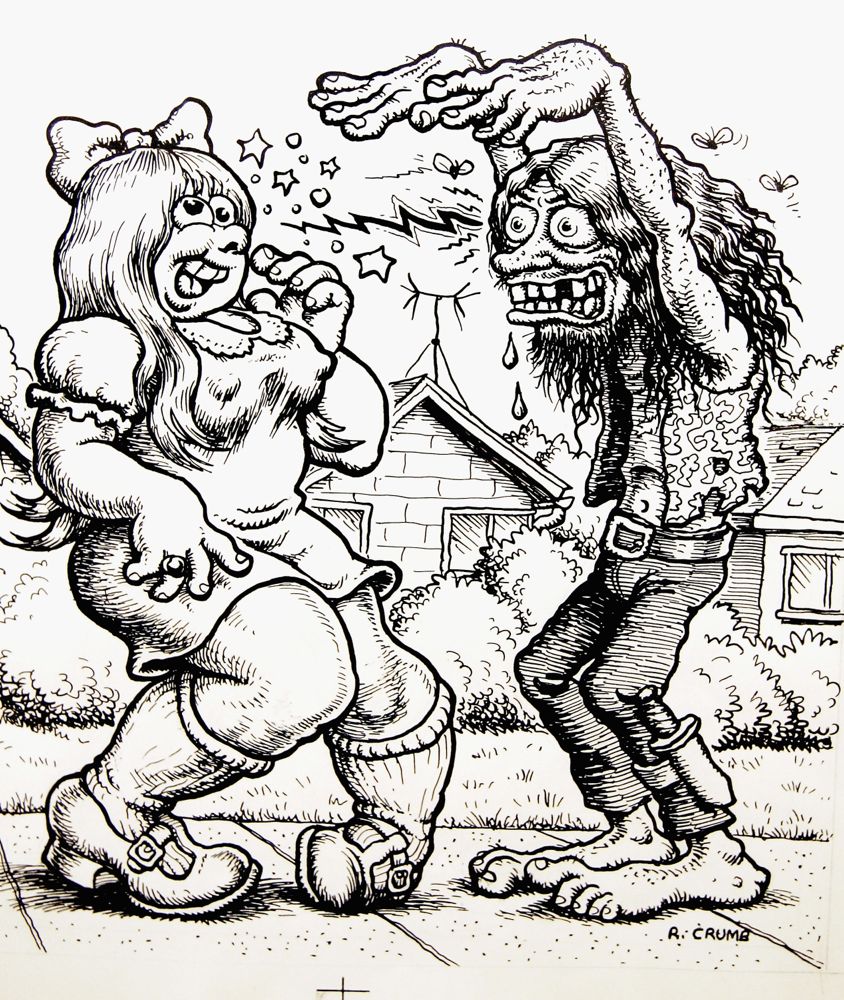

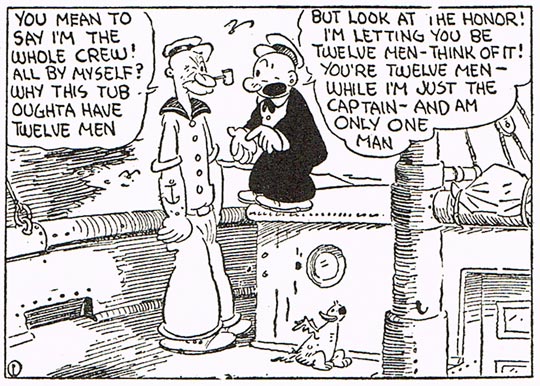

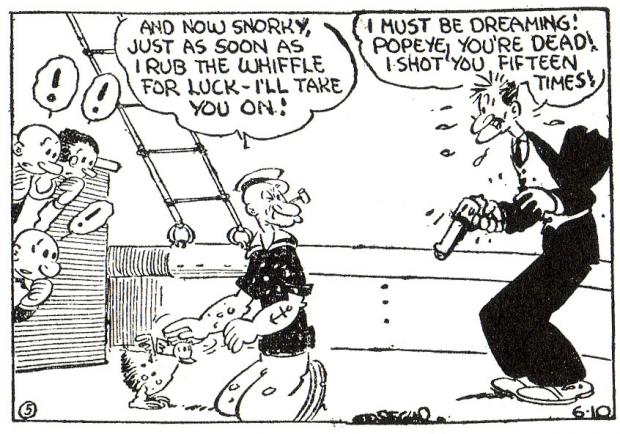

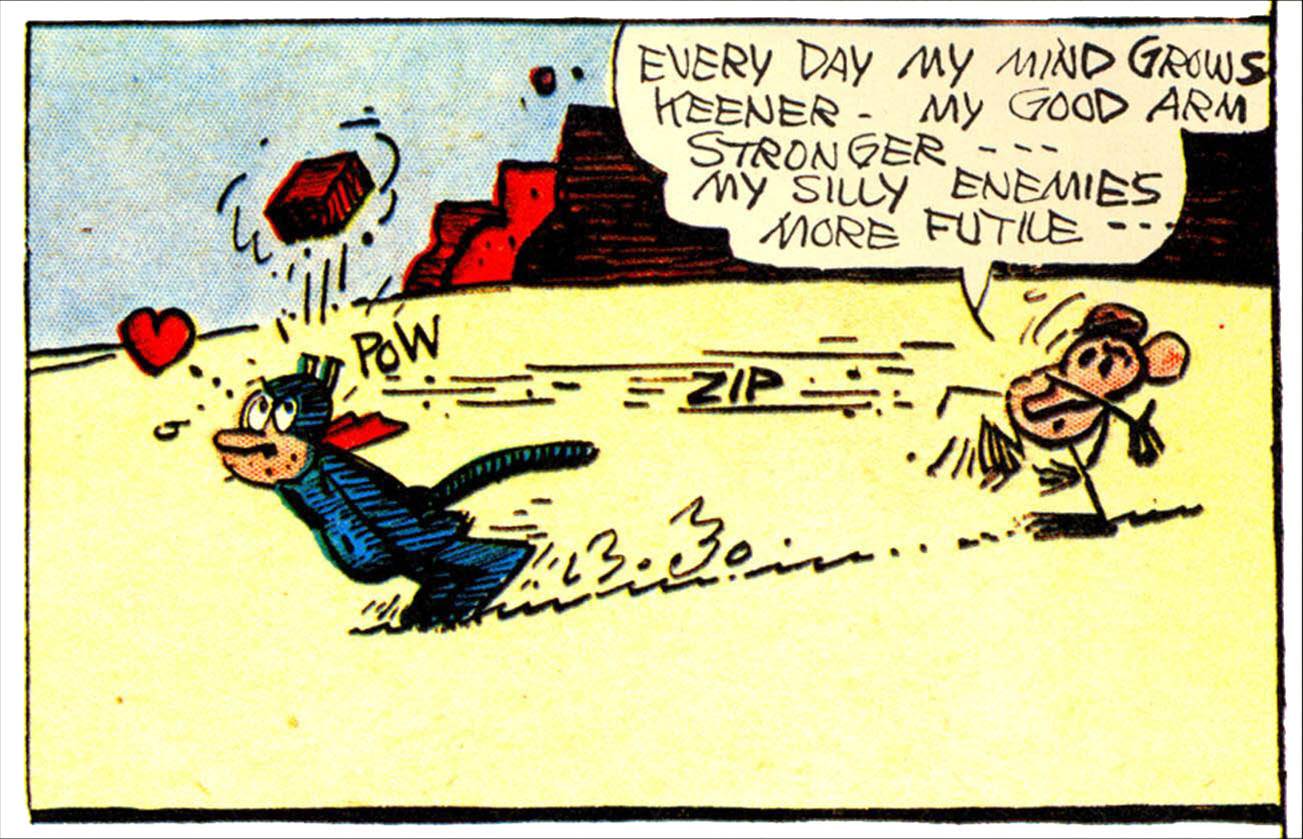

THE FUNNY PAPERS: POPEYE

Popeye the sailor man first appeared as a secondary character ten years into the run of E. C. Segar’s comic strip Thimble Theatre, which offered up parodies of dumb Hollywood movies. Almost instantly, however, he took over the strip. Violent, indestructible and bound by his own code of rough honor, he was irascible but dependable — the perfect protagonist for the wacky adventure strip Thimble Theatre turned into.

The strip featured surreal and whimsical fantasy elements and regular episodes of wild anarchic action, with Popeye inevitably having to beat the bejesus out of some villain or other.

The whole thing is eccentric, sui generis — and one of the most inventive and entertaining of all comic strips. Popeye got toned down as a character in the animated cartoons he eventually starred in, and in the incarnations of the comic strip after Segar’s untimely death at the age of 43. The character created by Segar remains a true American original, though — a brawling pigheaded palooka with a heart of gold.

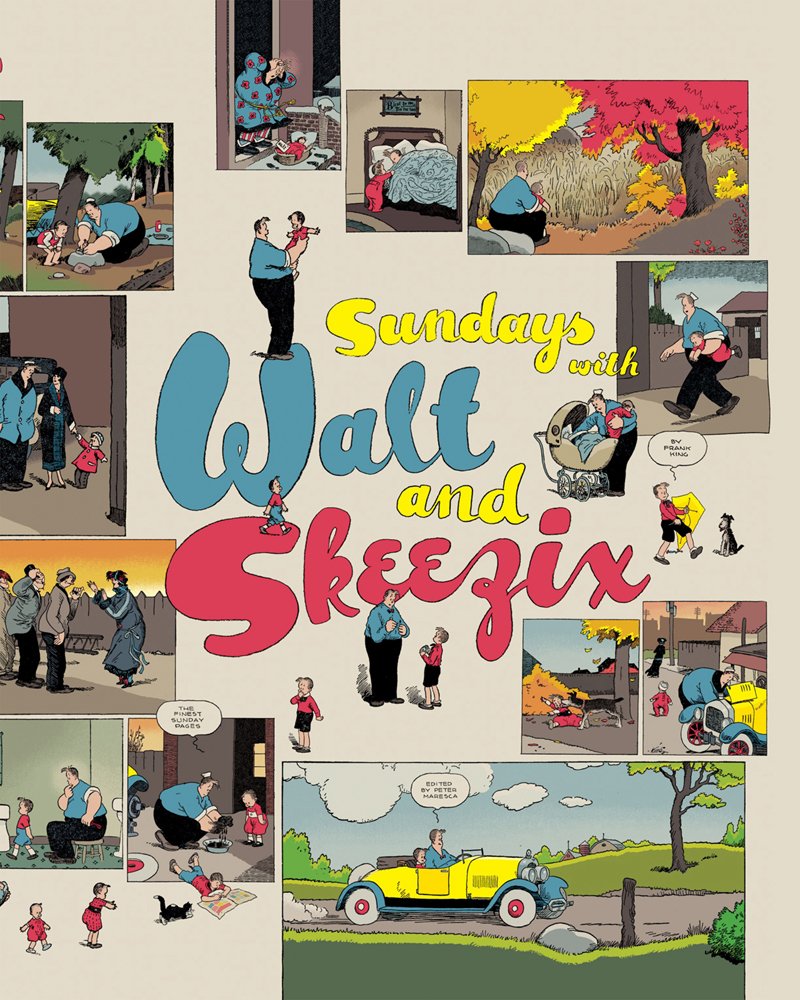

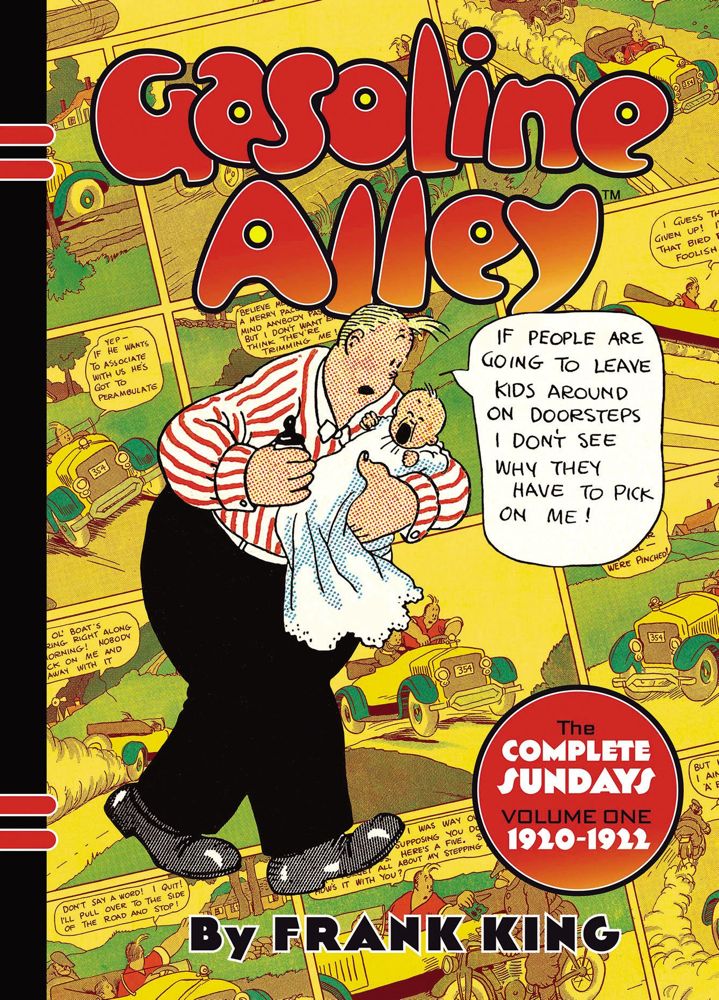

THE FUNNY PAPERS: GASOLINE ALLEY ON SUNDAY

As Drawn and Quarterly Press continues its reprinting of all the Gasoline Alley daily strips, other publishers offer collections of Frank King’s remarkable Sunday pages.

Sunday Press Books has published Sundays With Walt and Skeezix, one of its gargantuan and beautifully produced volumes reprinting a selection of the Sunday pages in their original size. It’s a book every lover of the funny papers should own. I wrote about it here — Unspeakably Cool.

More recently Dark Horse Books has started a series that will eventually reprint all the Sunday pages in chronological order. Slightly smaller than the Sunday Press volume, but still generously sized, these books are also a must for fans of Frank King, Gasoline Alley and the American comic strip.

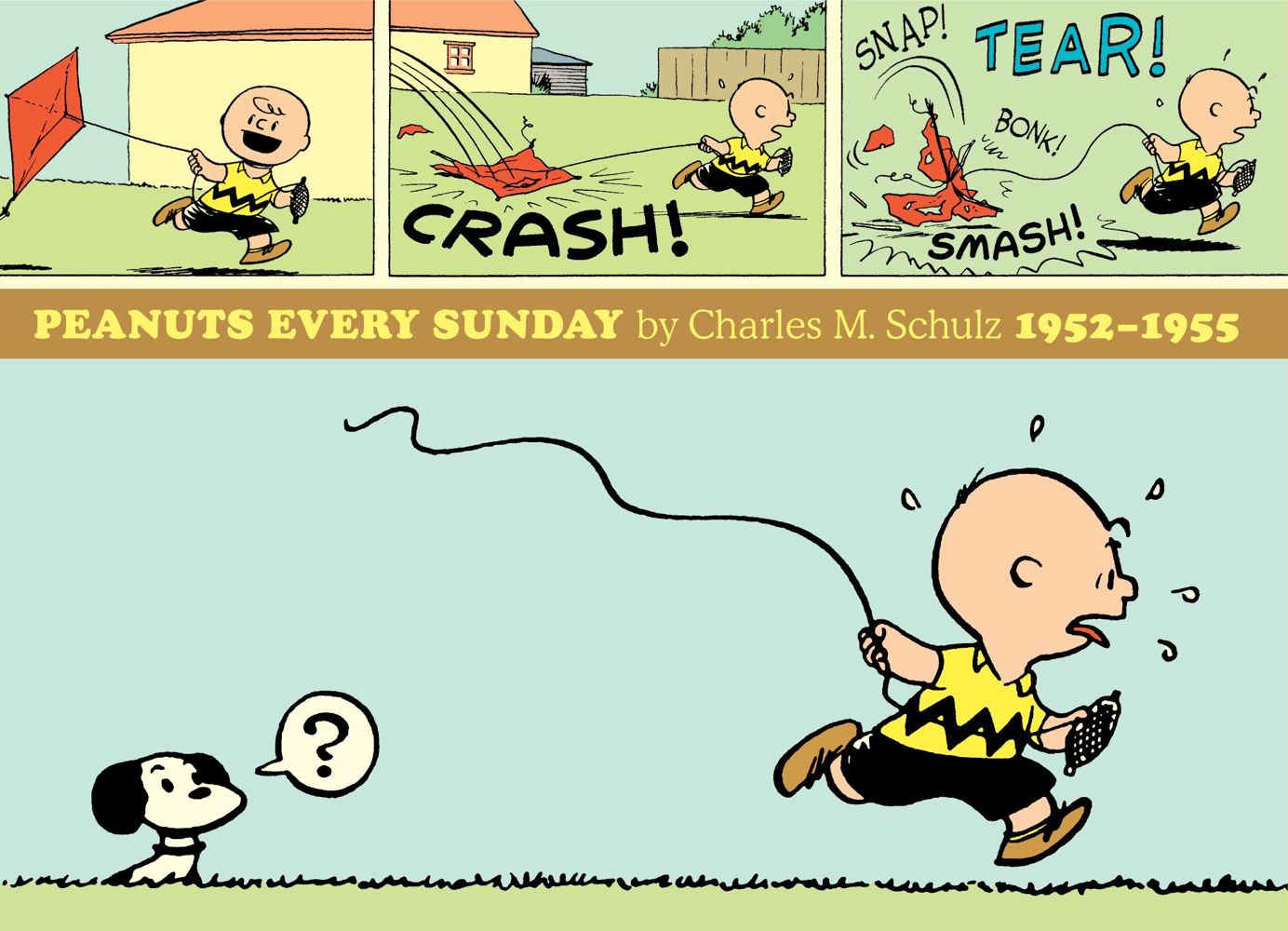

THE FUNNY PAPERS: PEANUTS ON SUNDAY

If you’re a fan of Peanuts but don’t feel the need to own every single Peanuts strip ever published — which Fantgraphics Books is in the process of reprinting in multiple volumes — Fantagraphics offers an attractive alternative. They’re also issuing collections of all the Sunday strips in color, in large-format editions. (Their Complete Peanuts volumes reproduce the Sunday strips in a smaller format and in black-and-white.)

They’re delightful books and probably offer more than enough Peanuts for most people.

Click on the image to enlarge.

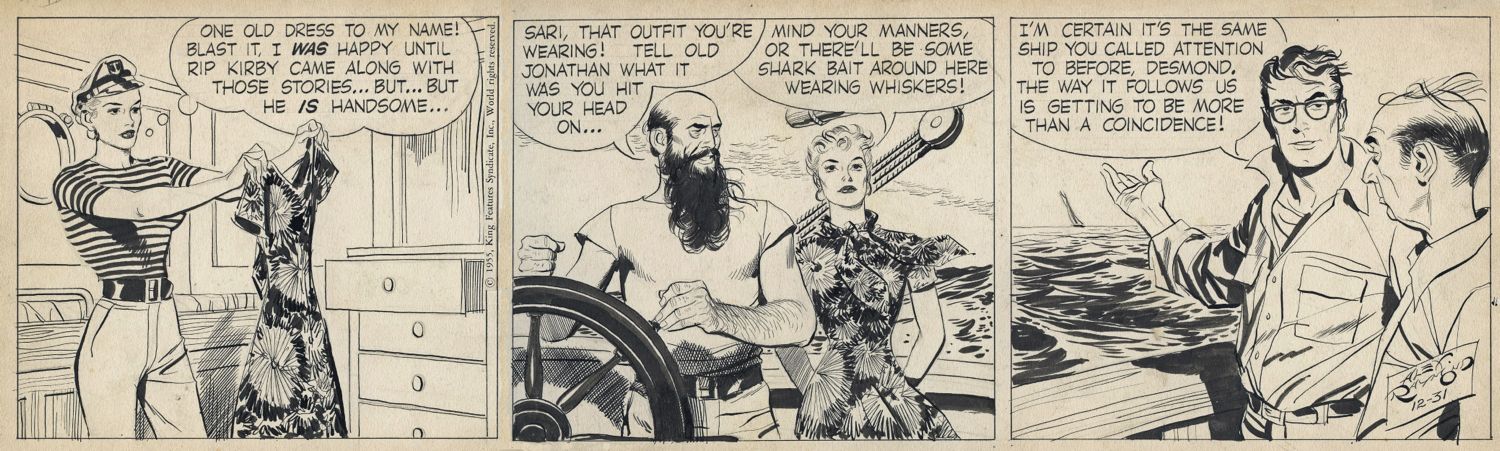

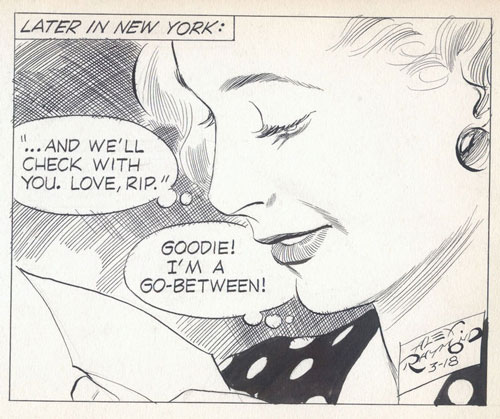

THE FUNNY PAPERS: RIP KIRBY

Click on the image to enlarge.

The legendary Alex Raymond made his name drawing the sci-fi fantasy comic strip Flash Gordon but went on to create several other important strips, including his last one, Rip Kirby, featuring a private detective in post-WWII New York. Raymond was primarily an artist collaborating with writers who supplied his plots and dialogue, but he was a brilliant artist, with a clean, bold, dynamic style that influenced many comic strip artists of later generations. George Lucas has said that Raymond’s Flash Gordon was a primary influence on the Star Wars films.

For Rip Kirby, Raymond employed a naturalistic style and dynamically composed panels that have a film noir feel to them. The strip is fast-moving and suspenseful and very entertaining. IDW Publishing is in the process of issuing reprints of the complete run of the strip in multiple volumes. It’s well worth a look.

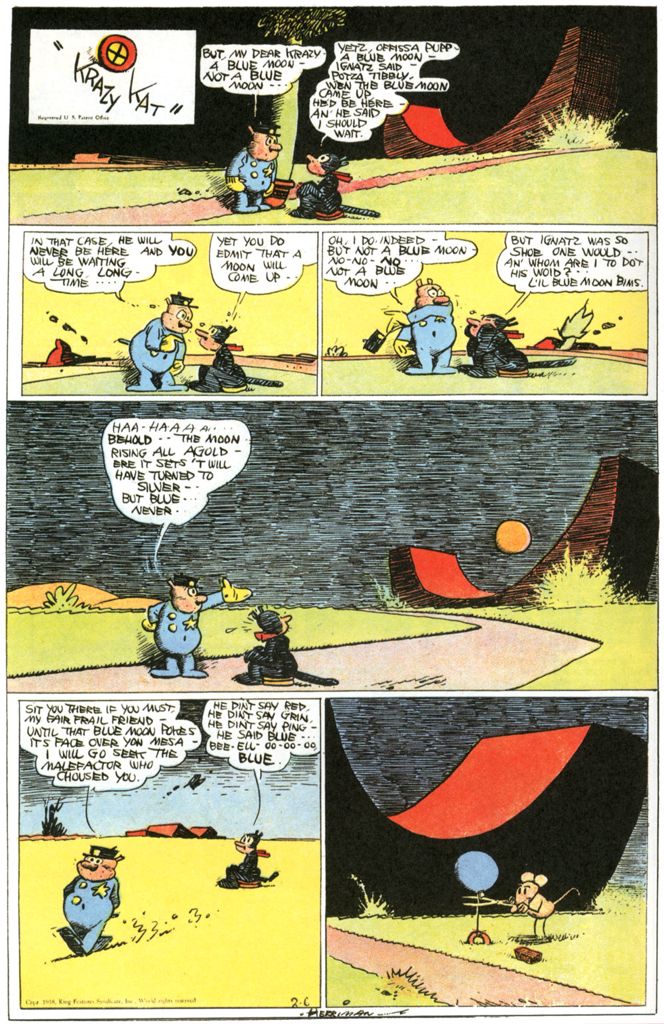

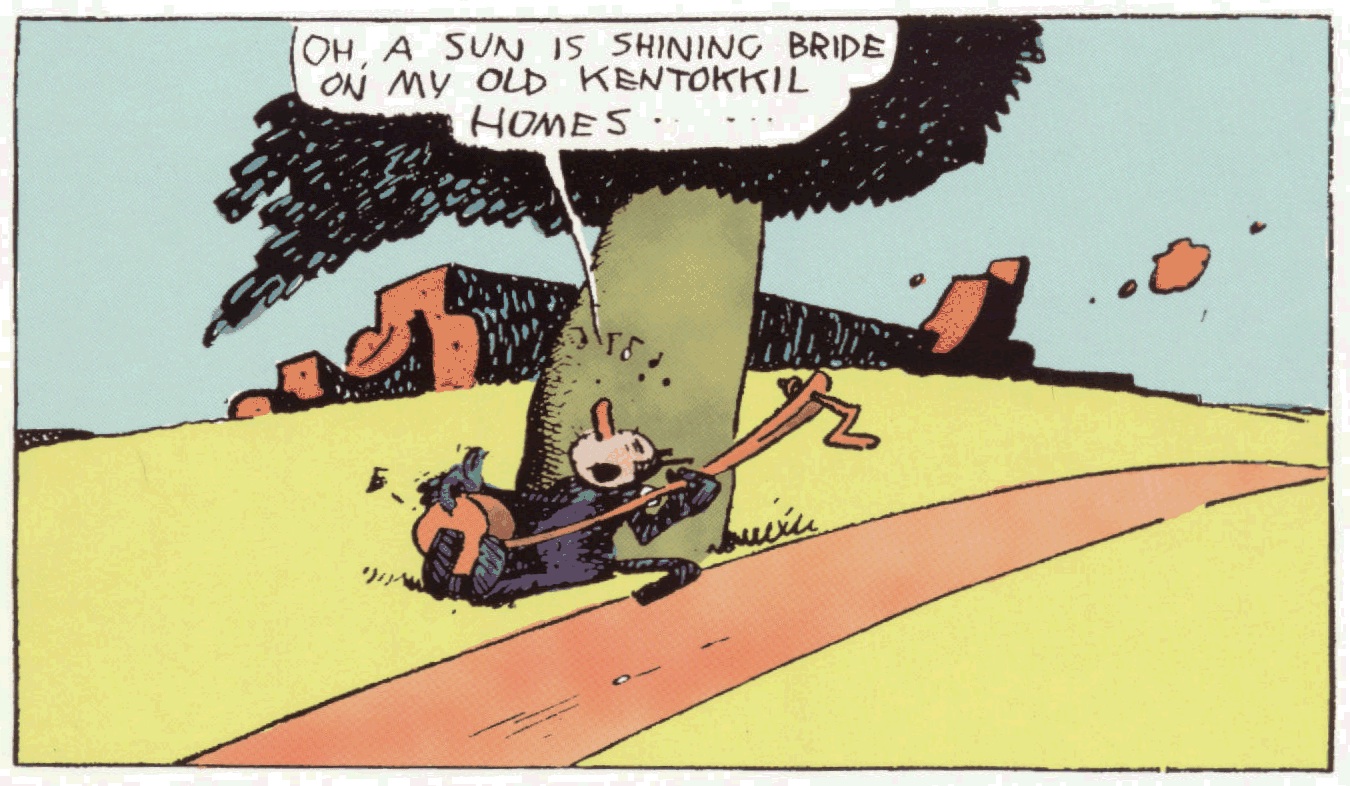

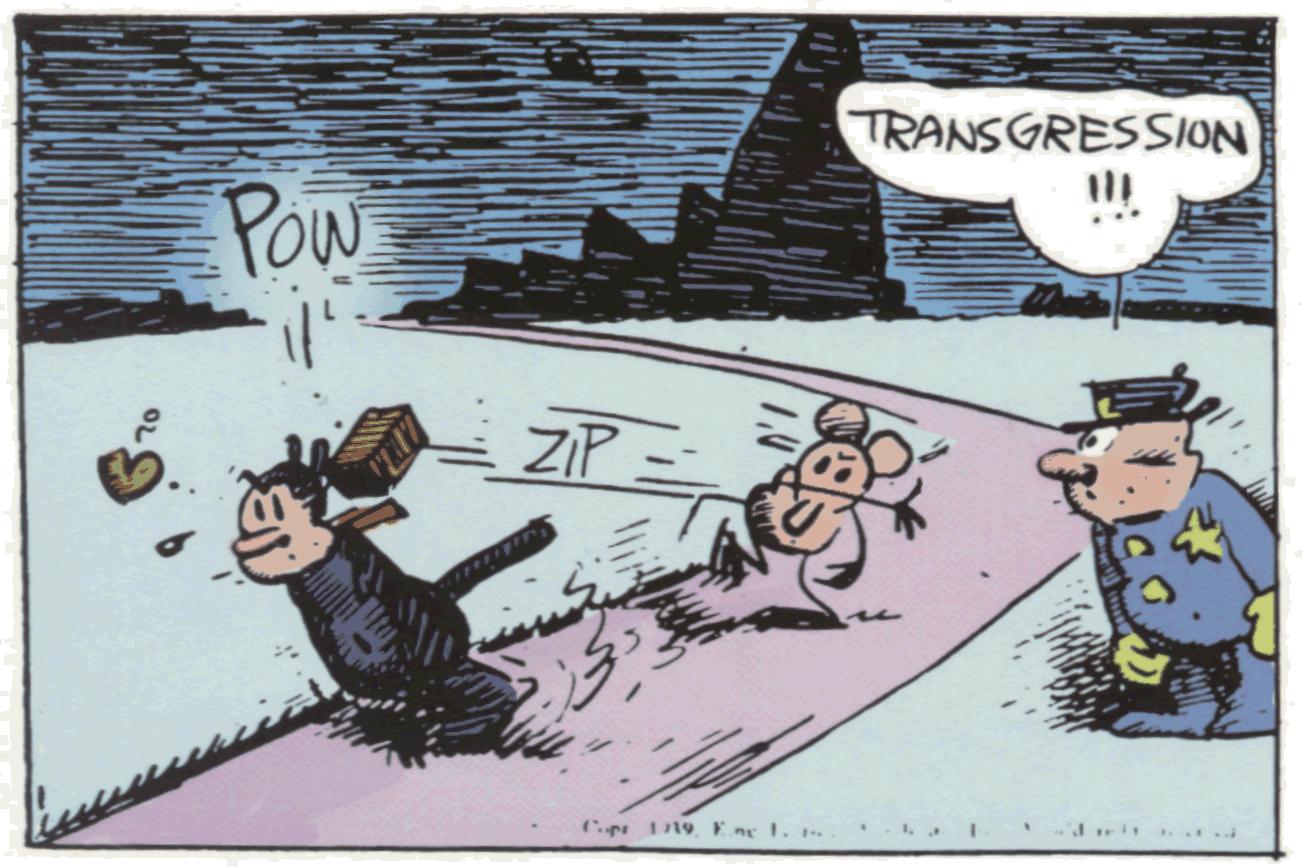

THE FUNNY PAPERS: KRAZY KAT

Many people consider this series the pinnacle of comic strip art, and it’s hard to argue with the proposition. George Herriman had a distinctive and brilliant visual style — the lines of his drawings are alive with an electric energy you find only in the work of the greatest graphic artists, from Rembrandt to Callot to Steinberg..

Herriman created a world based on the landscapes of the American Southwest, often referencing the area in and around around Monument Valley, and sometimes distorting its unusual natural features into purely abstract forms. (Cartoonists and painters discovered Monument Valley long before John Ford turned it into an iconic setting for Western movies.)

In Herriman’s dreamlike Southwest he conjured up a kind of mythic love triangle between three anthropomorphized animals — Krazy, a cat, Ignatz, a mouse, and Officer Pupp, a dog. Krazy loves Ignatz, Ignatz cares only for bashing Krazy with bricks (which Krazy insists on seeing as a sign of affection), and Pupp lives only to protect the innocent Krazy and bring Ignatz to justice.

The dynamics of the triangle never change – they’re played out in endless variations over decades, as other anthropomorphized animals in the community look on, pursuing their own quirky business on the fringes of the central drama.

It’s all very strange, and wonderful. Motives are never quite spelled out — it isn’t even clear if Krazy is male or female. He or she is sweetly philosophical, in an optimistic vein, about everything that happens. Ignatz’s unwavering determination to hit Krazy with bricks takes on a kind of heroic dimension, and Pupp’s admirable but hopeless pursuit of justice becomes comical, almost pathetic.

This is just the way life is, Herriman seems to be saying — no use trying to judge it or to fix it.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the strip was never terribly popular. William Randolph Hearst admired it, though, considered it an adornment to his newspapers and insisted that they keep running it year after year. It was undoubtedly his greatest contribution to American culture.

Fantagraphics Books has published the complete run of the full-page strips, in black and white, in multiple volumes, as well as a collection of the panoramic daily strips from the 1920s. Sunday Press has published a fabulous over-sized collection of the Sunday strips in color. They’re all worth owning and revisiting often.

Click on the images to enlarge.

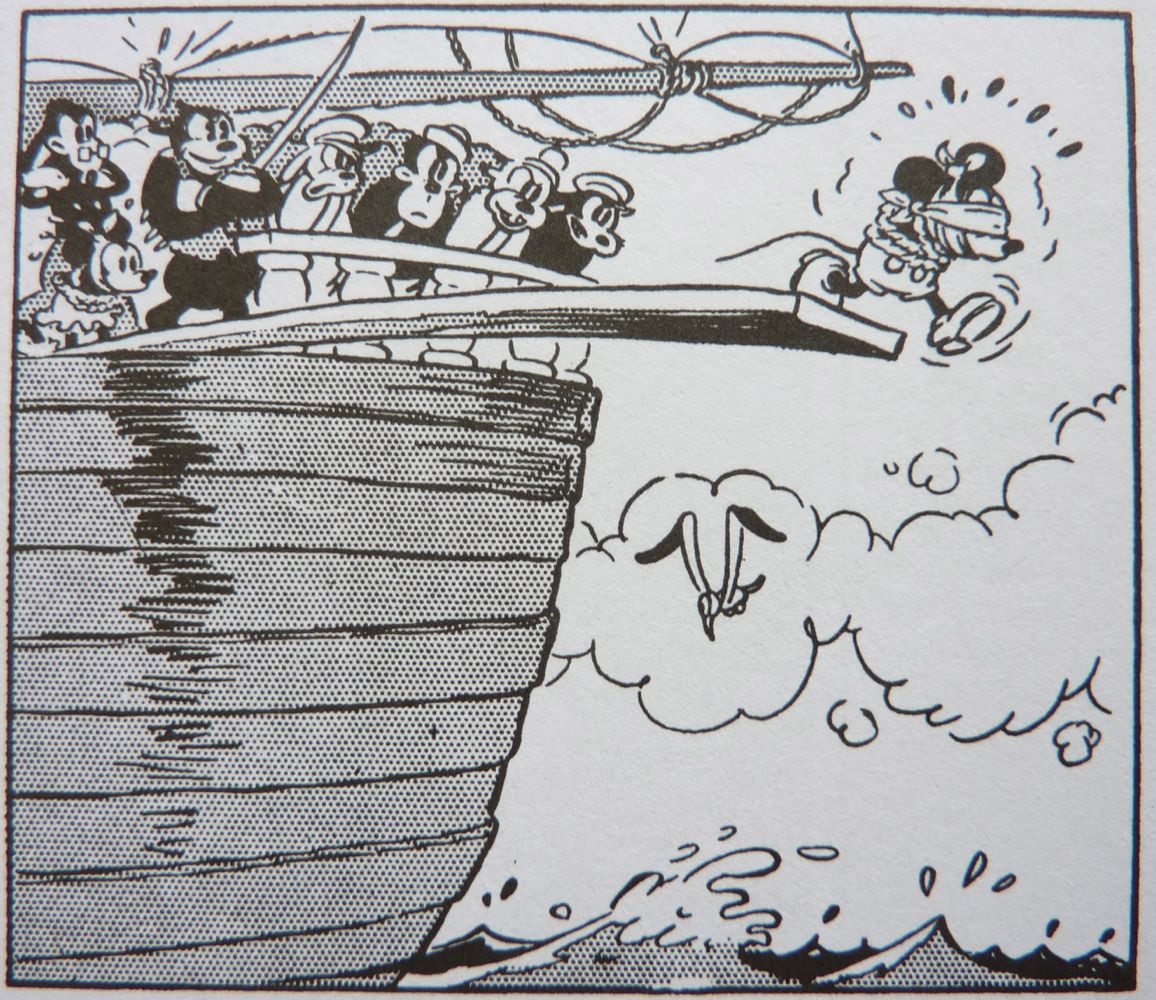

THE FUNNY PAPERS: MICKEY MOUSE

For many years — 45 to be exact — Floyd Gottfredson drew the Disney Mickey Mouse comic strips for newspapers, often then collected in books. They generally, except at the end of the strip’s run, involved extended adventure tales.

Gottfedson didn’t have the genius of Carl Barks, who drew the Donald Duck comic books for Disney, and he had a series of collaborators on the strips over the years, various inkers and dialogue writers who came and went, but his was the presiding vision. He was a fine artist and visual storyteller, and the Mickey strips are very entertaining.

Fantagraphics Books is in the process of reprinting the complete run of them. Sadly, the strips in the Fantagraphics books are printed too small. Gottfredson often drew very busy panels and crammed a lot of text into description boxes and dialogue balloons. Some of the panels in the Fantagraphics volumes can’t be deciphered without a magnifying glass.

Click on the images to enlarge.

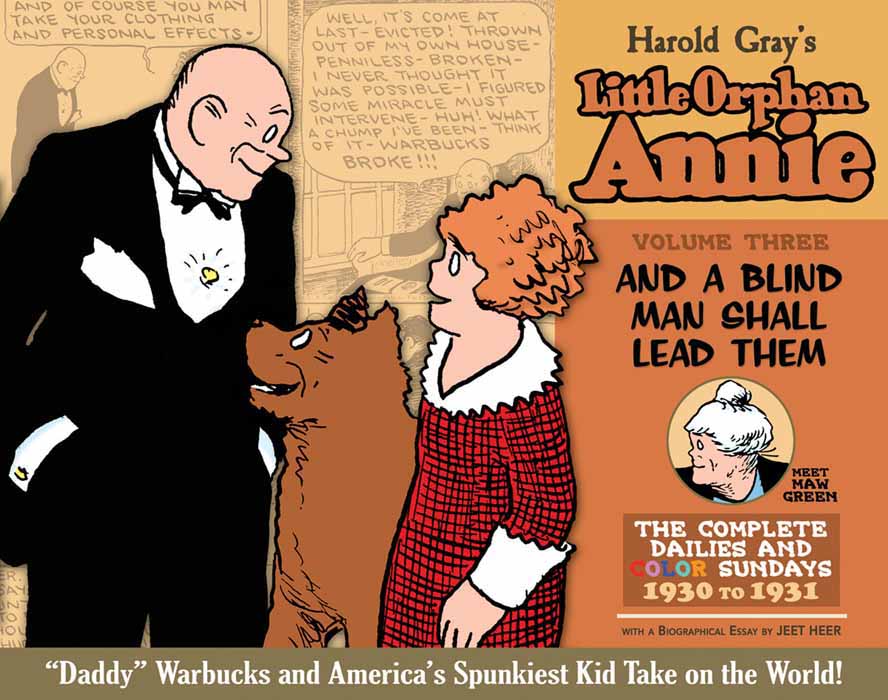

THE FUNNY PAPERS: LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE

This is a very unusual comic strip — it features a plucky young girl as it’s protagonist. She is, of course, an orphan who at the start leads a hard-luck life in an orphanage run by a mean matron who tries to instill in her charges the idea that they are second-class human beings.

Annie suffers her hardships with stoic good grace but never accepts second-class status — she believes in herself, is willing to stick up for herself, is capable of defending herself and others if they’re physically assaulted, and has an unshakeable spirit of personal honor and generosity.

Although the strip began in the mid 1920s, Annie would in time come to be seen as the personification of the decency and grit that got America through the Great Depression, and she is certainly one of the most powerful female icons in all of American art, a successor to Dorothy Gale and precursor to Velvet Brown.

I’m still working my way through the early years of the strip, which concentrate on Annie’s Dickensian travails as an orphan. Eventually she will find a powerful mentor and patron in Daddy Warbucks and go off on exotic adventures, carrying her heroic virtues into the wide world.

Heroic as she is, however, she’s also unassuming and funny, with a wry perspective on things, a distinctly American sort of hero — but always a girl to keep your eye on, a girl to rely on when the going gets tough.

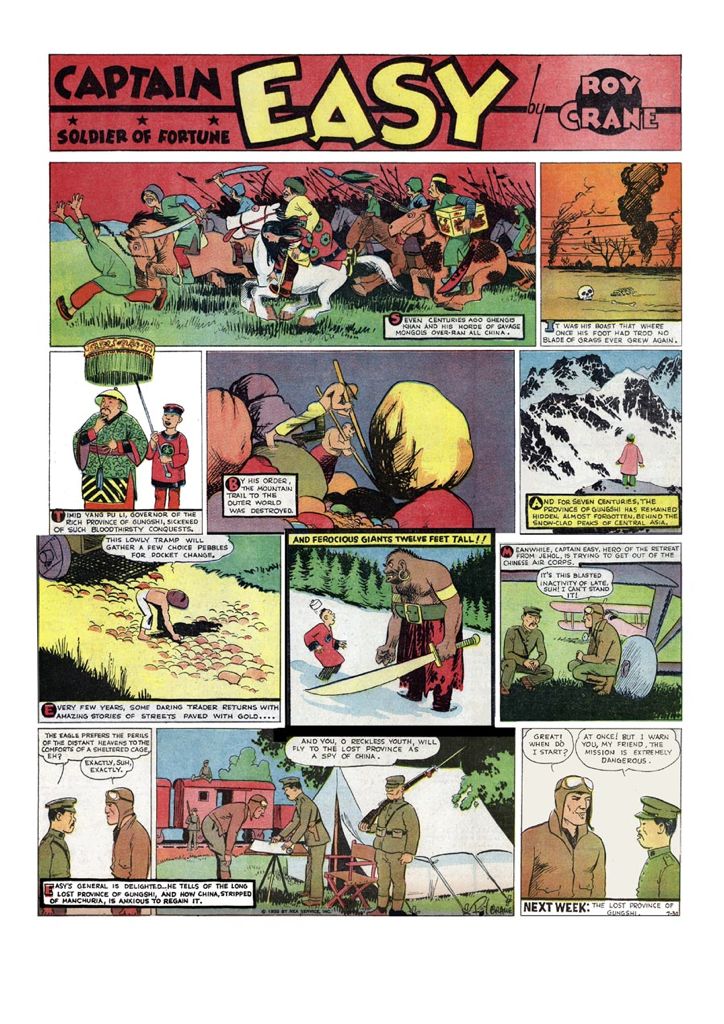

THE FUNNY PAPERS: CAPTAIN EASY, SOLDIER OF FORTUNE

Roy Crane pioneered the action-adventure comic strip with Wash Tubbs. The character Tubbs started out as bumbling grocery store clerk but Crane decided he didn’t like the gag-a-day format and started sending Tubbs off on protracted adventures. Captain Easy, soldier of fortune, a secondary character in the strip, was better suited to this format and Crane developed a new Sunday strip centered around him.

These Sunday strips have been reprinted by Fantagraphics Books, well reproduced in four large-format books. Crane’s drawing style is just serviceable and his adventure tales a bit bland and formulaic at times, but it’s a genial strip, fairly diverting and important historically.

Worth a look, especially in the gorgeous Fantagraphics reprint editions.

Click on the image to enlarge.

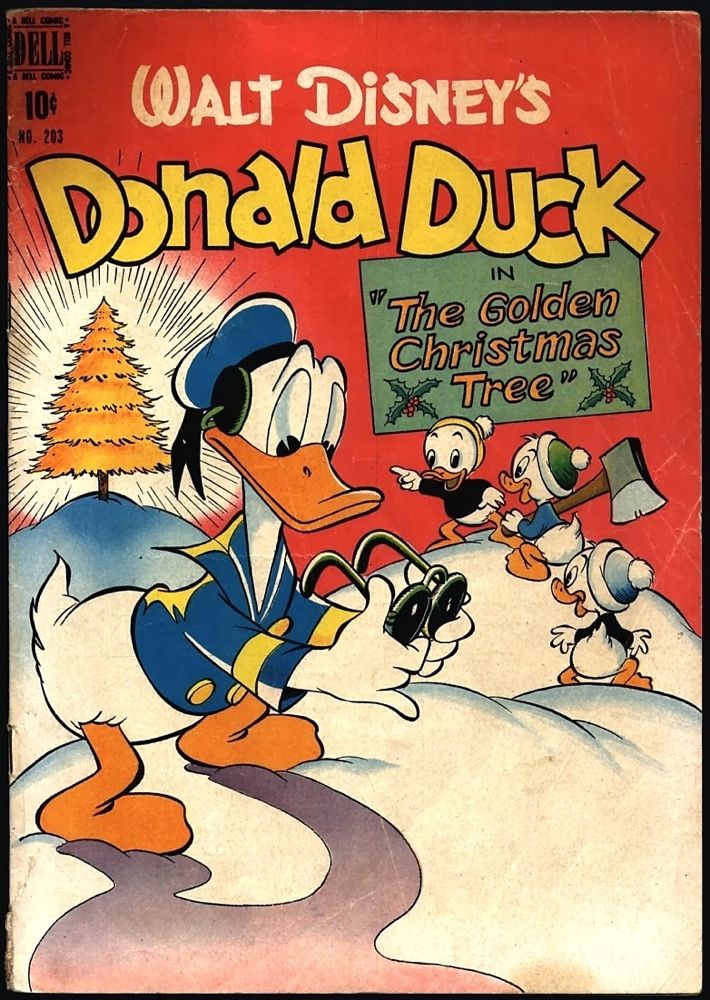

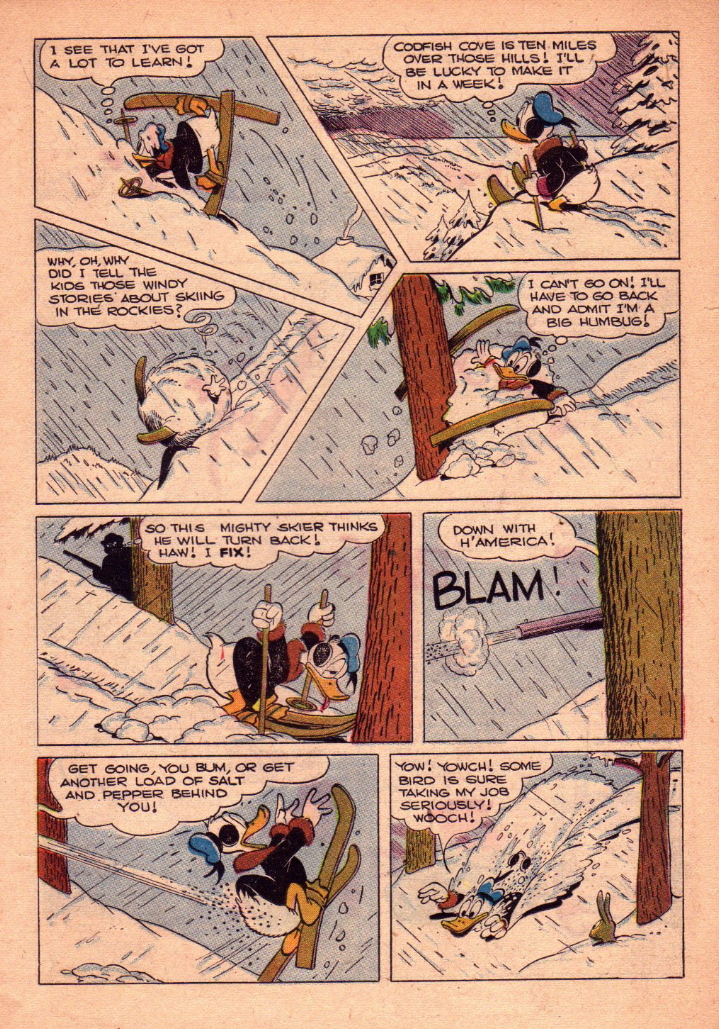

THE FUNNY PAPERS: CARL BARKS

Carl Barks didn’t actually appear in the funny papers — he drew comic books — but he is one of the finest of all comic strip artists.

His style of visual narrative is deceptively simple. His panels rarely draw attention to themselves — they’re well-crafted but straightforward — and yet his stories pop from frame to frame, with a speed and economy that are thrilling. You might call him the Howard Hawks of comic strip artists, with a technique so masterful that it disappears in the beguilements of the tale.

Barks’s humor is gentle, more amusing and charming than funny, but the sweetness draws you into his adventure plots with Donald and his nephews and his Uncle Scrooge in an oddly powerful way. His is a cozy and consoling art, pleasurable in ways that seem to bypass the conscious mind and return you to the innocent diversions of childhood, like pretending to be a jungle explorer in the blackberry thickets down by the river.

It’s art of a very high order.

Click on the images to enlarge.

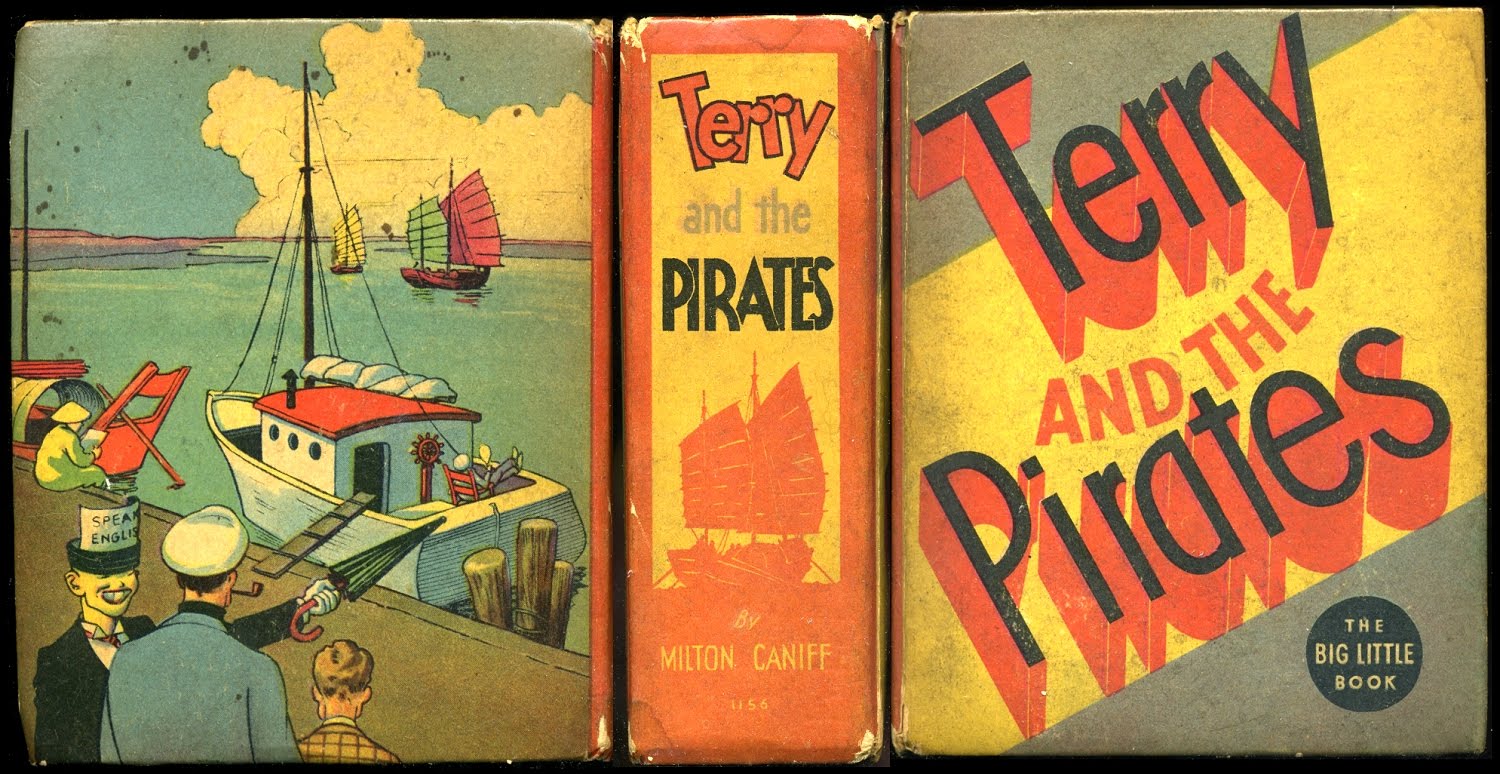

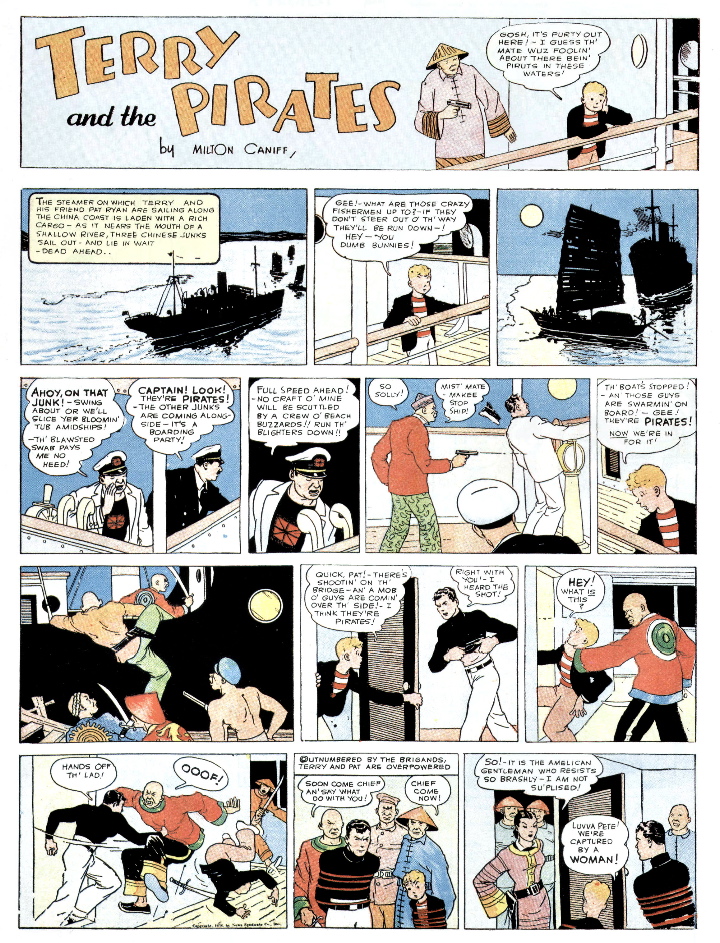

THE FUNNY PAPERS: TERRY AND THE PIRATES

This is the best of all the action-adventure comic strips, and one of the most brilliant comic strips ever created in any genre.

The narratives are boys-own-adventure stuff — literally, because the main protagonist is, at least when the strip begins, a young teenaged boy named Terry Lee. He and his adult mentor Pat Ryan, a journalist by trade, find themselves in China and have a series of wild adventures among Chinese warlords and pirates, among them their nemesis The Dragon Lady, a beautiful but wicked pirate queen.

The draftsmanship of the strip’s creator Milt Caniff is dazzling, wonderfully evoking the exotic locales, but Caniff’s greatest skill is visual storytelling in passages of dynamic panels that hurtle through exciting action sequences.

Orson Welles was an ardent admirer of the strip, and you can see why — Caniff’s method was visually elegant and thrillingly cinematic.

It’s just great stuff.

Click on the images to enlarge.

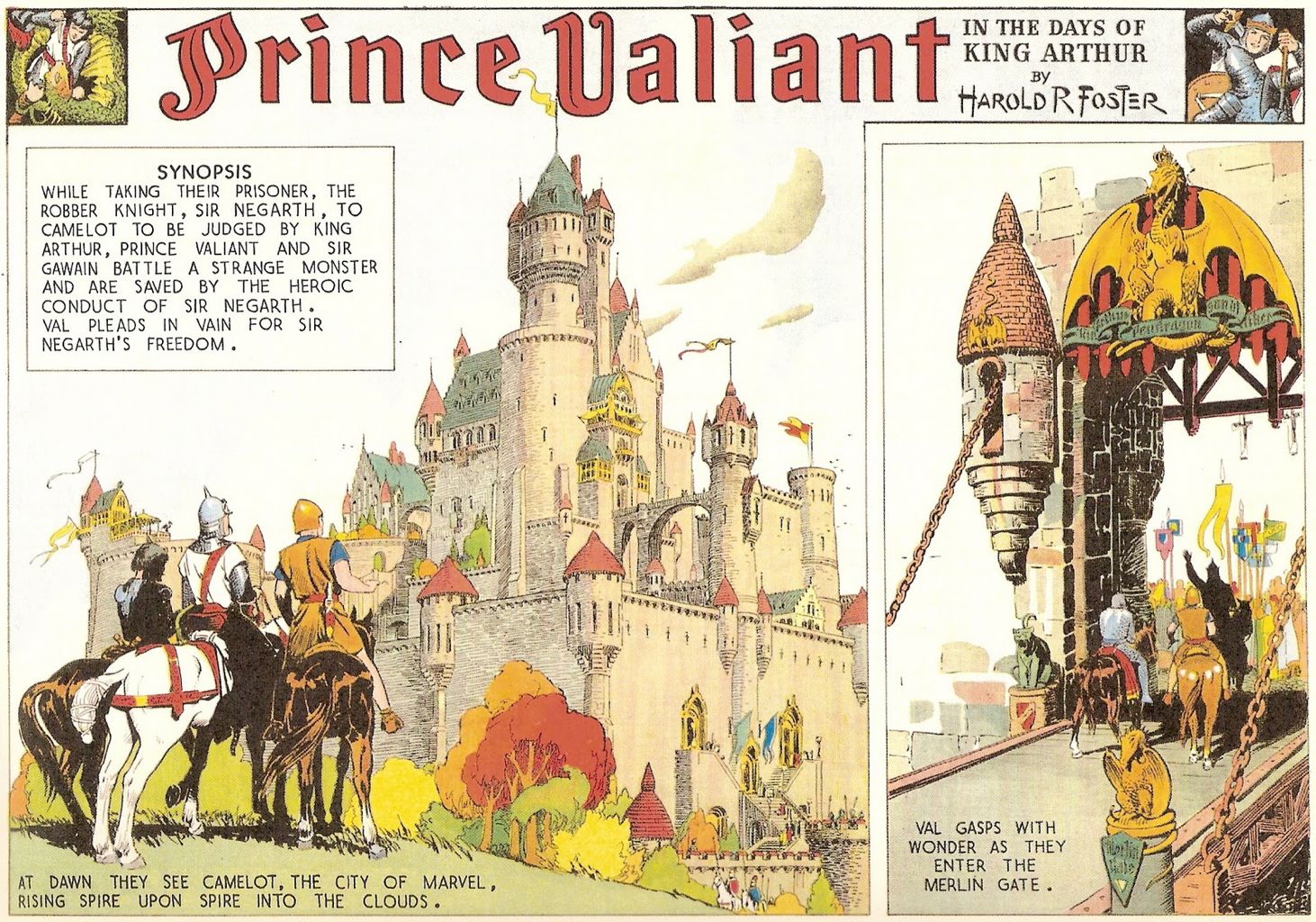

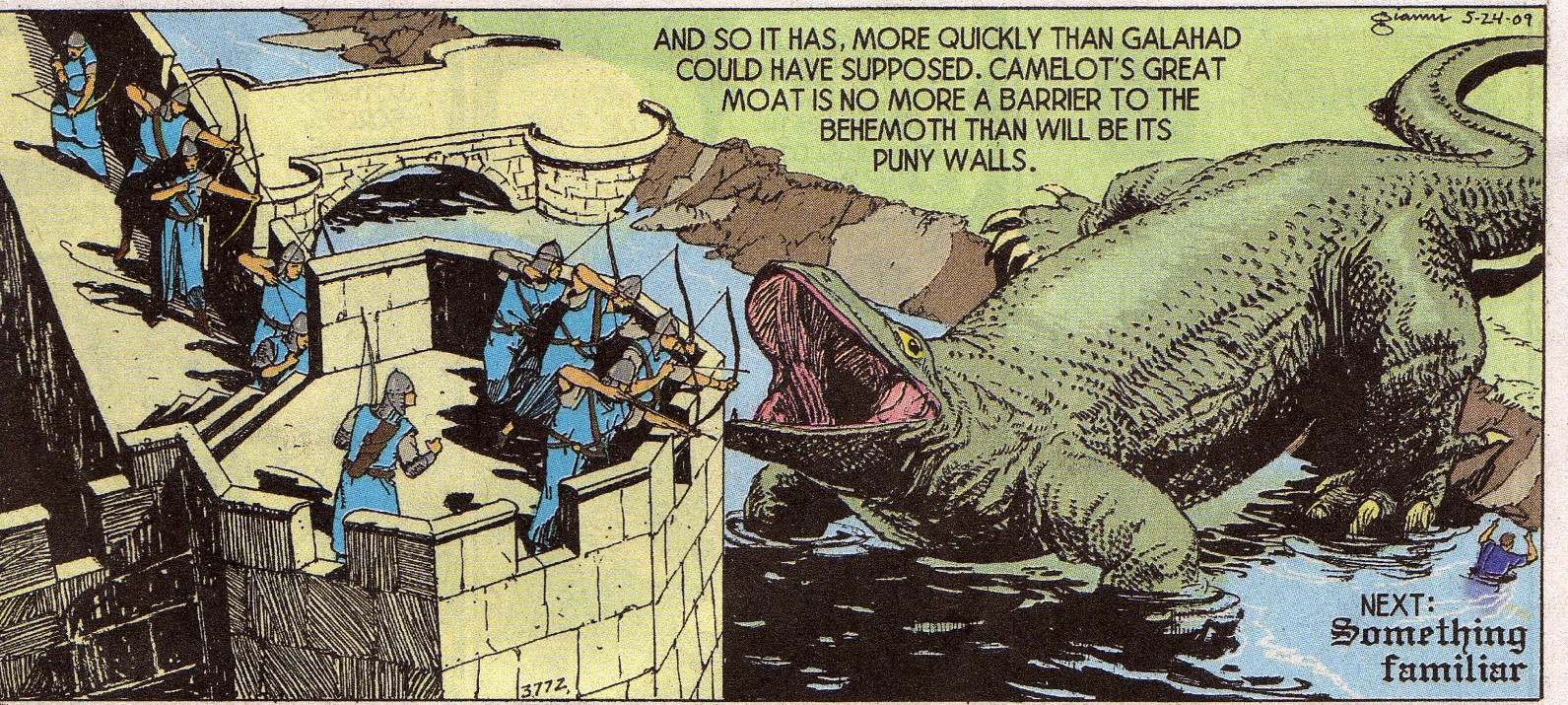

THE FUNNY PAPERS: PRINCE VALIANT

Prince Valiant is the most beautifully drawn of all the classic action-adventure comic strips. Its author Hal Foster was a brilliant draftsman and just about every image he ever drew was arresting. He employed large panels that contained lots of detail, but they didn’t work together in a dynamic way, like the shots in a movie, giving the narrative visual momentum.

The strip thus has a kind of static, or perhaps you could say stately, quality — more oriented towards the pictorialism of book illustrations than towards the cinematic energy of most action-adventure strips. Foster relied heavily on blocks of expository text to move his tales forward from one gorgeous image to the next.

Still, it’s a delightful and entertaining strip, aesthetically compelling, and the tales themselves are satisfying yarns, full of chivalric derring-do and spectacular fantasy.

Click on the images to enlarge.

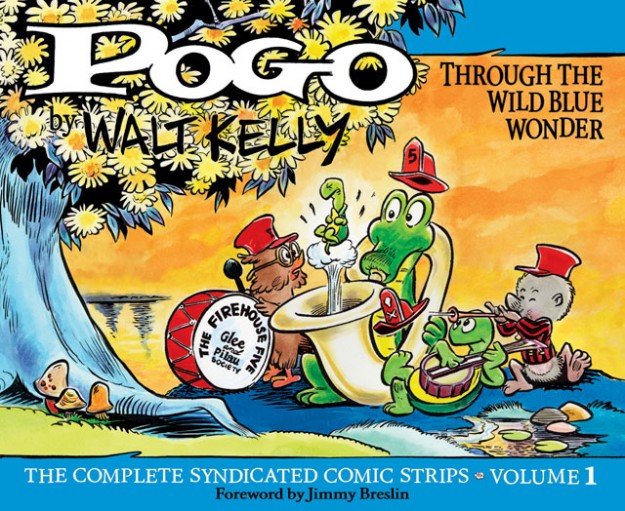

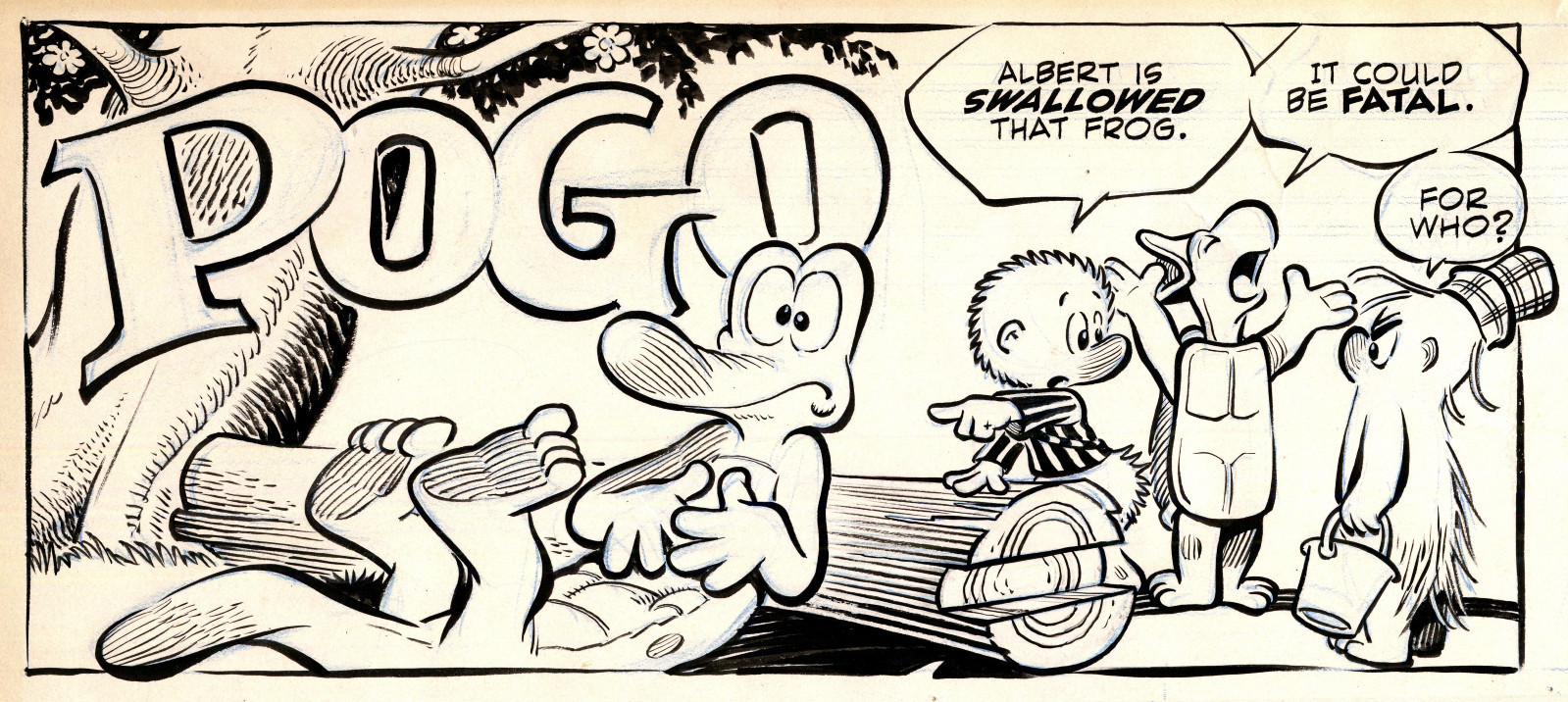

THE FUNNY PAPERS: POGO

Complete runs of most of the great strips from the Golden Age of American comics have been or are being issued in excellent editions by the likes of Fantagraphics Books, IDW Publishing and Sunday Press Books. I’m a collector of many of these reprint series, working my way through them with great pleasure. Here’s a report on my progress through Pogo:

Click on the image to enlarge.

Like Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, Walt Kelly’s comic strip Pogo got off to a slow start. It creates a world located in the Okefenokee Swamp peopled by anthropomorphized swamp critters. The episodes involve a laconic backwoods sort of humor that isn’t always terribly funny or insightful. It’s just pleasant, in an off-hand way, though the drawing is consistently impressive. I never read the strip with much attention when it was first appearing but I’m told it moved eventually into a mode of social and political satire that was penetrating.

We shall see.